Unrevised Transcript of Evidence Taken Before the Select Committee on Science and Technology ENGINEERING and PHYSICAL SCIENCES R

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ISIS Annual Review 2012

Pulsed Neutron and Muon Source Review of the Year 2012 ISIS 2012 ISIS 2012 was produced for the ISIS Facility, STFC Rutherford Appleton Laboratory, Harwell Oxford, Didcot, Oxfordshire, OX11 0QX, UK ISIS Director, Prof Robert McGreevy 01235 445599 ISIS User Office 01235 445592 ISIS Facility Web pages http://www.isis.stfc.ac.uk ISIS 2012 production team: David Clements, Felix Fernandez-Alonso, Hanna Fikremariam, Tatiana Guidi, Philip King, Anders Markvardsen, Stewart Parker, Rob Washington. Design and layout: Ampersand Design Ltd, Wantage. September 2012 © Science and Technology Facilities Council 2012 Enquiries about copyright, reproduction and requests for additional copies of this report should be addressed to: STFC Library and Information Services, Rutherford Appleton Laboratory, Harwell Science and Innovation Campus, Didcot, Oxfordshire, OX11 0QX email: [email protected] Neither the Council nor the Laboratory accept any responsibility for loss or damage arising from the use of information contained in any of their reports or in any communication about their tests or investigations. ISIS PULSED NEUTRON AND MUON SOURCE ISIS 2012 ISIS provides world-class facilities for neutron and muon investigations of materials across a diverse range of science disciplines. ISIS 2012 details the work of the facility over the past year, including accounts of science highlights, descriptions of major instrument and accelerator developments and the facility’s publications for the past year. CONTENTS 3 Foreword 6 Science highlights 8 Soft Matter and Biomolecular -

Thesis Template (Double-Sided)

CRANFIELD UNIVERSITY Yiarayong Klangboonkrong Modes of knowledge production: Articulating coexistence in UK academic science School of Management PhD Academic Year: 2014-2015 Supervisor: Professor Mark Jenkins July 2015 CRANFIELD UNIVERSITY School of Management PhD Thesis Academic Year 2014-2015 Yiarayong Klangboonkrong Modes of knowledge production: Articulating coexistence in UK academic science Supervisor: Professor Mark Jenkins July 2015 © Cranfield University 2015. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced without the written permission of the copyright owner. ABSTRACT The notion of Mode 2, as a shift from Mode 1 science-as-we-know-it, depicts science as practically relevant, socially distributed and democratic. Debates remain over the empirical substantiation of Mode 2. In particular, our understanding has been impeded by the mutually exclusive framing of Mode 1/Mode 2. Looking at how academic science is justified to diverse institutional interests – a situation associated with Mode 2 – it is asked, “What happens to Mode 1 where Mode 2 is in demand?” This study comprises two sequential phases. It combines interviews with 18 university spinout founders as micro-level Mode 2 exemplars, and macro-level policy narratives from 72 expert witnesses examined by select committees. An interpretive scheme (Greenwood and Hinings, 1988) is applied to capture the internal means-ends structure of each mode, where the end is to satisfy demand constituents, both in academia (Mode 1) and beyond (Mode 2). Results indicate Mode 1’s enduring influence even where non-academic demands are concerned, thus refuting that means and ends necessarily operate together as a stable mode. The causal ambiguity inherent in scientific advances necessitates (i) Mode 1 peer review as the only quality control regime systematically applicable ex ante, and (ii) Mode 1 means of knowledge production as essential for the health and diversity of the science base. -

Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council Annual Report and Accounts 2010-2011

Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council EPSRC EPSRC EPSRC EPSRC EPSRC EPSRC EPSRC EPSRC EPSRC EPSRC EPSRC EPSRC EPSRC EPSRC EPSRC EPSRC EPSRC EPSRC EPSRC EPSRC EPSRC EPSRC EPSRC EPSRC EPSRC EPSRC EPSRC EPSRC EPSRC EPSRC EPSRC EPSRC EPSRC EPSRC EPSRC EPSRC EPSRC EPSRC EPSRC EPSRC EPSRC EPSRC EPSRC EPSRC EPSRC EPSRC EPSRC EPSRC EPSRC EPSRC EPSRC EPSRC EPSRC EPSRC EPSRC EPSRCANNUAL EPSRCREPORT AND EPSRC ACCOUNTS EPSRC EPSRC EPSRC EPSRC2010 -EPSRC 2011 EPSRC EPSRC EPSRC EPSRC EPSRC EPSRC EPSRC EPSRC EPSRC EPSRC EPSRC EPSRC EPSRC EPSRC EPSRC EPSRC EPSRC EPSRC EPSRC EPSRC EPSRC EPSRC EPSRC EPSRC EPSRC EPSRC EPSRC EPSRC EPSRC EPSRC EPSRC EPSRC EPSRC EPSRC EPSRC EPSRC EPSRC EPSRC ENGINEERING AND PHYSICAL SCIENCES RESEARCH COUNCIL ANNUAL REPORT AND ACCOUNTS 2010-2011 Presented to Parliament pursuant to Schedule 1 of the Science and Technology Act 1965 Ordered by the House of Commons to be printed on 24 November 2011 HC 1614 London: The Stationery Office £20.50 © Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council (2011) The text of this document (this excludes, where present, the Royal Arms and all departmental and agency logos) may be reproduced free of charge in any format or medium providing that it is reproduced accurately and not in a misleading context. The material must be acknowledged as Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council copyright and the document title specified. Where third party material has been identified, permission from the respective copyright holder must be sought. Any enquiries regarding this publication should be sent to us at: [email protected]. This publication is available for download at www.official-documents.gov.uk. -

Mathematical Sciences Research

sip SPRING 2013 4/2/13 12:22 Page 1 SCIENCE IN PARLIAMENT Chemical engineering – a vital part of the 21st Century jigsaw sip SPRING 2013 The Journal of the Parliamentary and Scientific Committee www.scienceinparliament.org.uk sip SPRING 2013 4/2/13 12:22 Page 2 Source: Deloitte The Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council The Council for the Mathematical Sciences (CMS) (EPSRC) is the UK’s main agency for funding research in provides an authoritative and objective body that exists to engineering and physical sciences. EPSRC invests around develop, influence and respond to UK policy issues that £800 million a year in research and postgraduate training, affect the mathematical sciences in higher education and to help the nation handle the next generation of research, and therefore the UK economy and society in technological change. The areas covered range from general. Speaking with one voice for five learned information technology to structural engineering, and societies, the CMS represents the Institute of mathematics to materials science. This research forms the Mathematics and its Applications, the London basis for future economic development in the UK and Mathematical Society, the Royal Statistical Society, the improvements for everyone’s health, lifestyle and culture. Edinburgh Mathematical Society and the Operational EPSRC works alongside other Research Councils, working Research Society. collectively on issues of common concern via Research Councils UK. The full report is available at http://www.epsrc.ac.uk/SiteCollectionDocuments/Publications/reports/DeloitteMeasuringTheEconomicsBenefits OfMathematicalScienceResearchUKNov2012.pdf sip SPRING 2013 4/2/13 12:22 Page 3 Surely nobody can have failed to notice that “Science” is SCIENCE IN PARLIAMENT everywhere these days? We had (Sir) Tim Berners Lee to help open the Olympics. -

Order Paper for Tue 5 Jun 2018

Tuesday 5 June 2018 Order Paper No.144: Part 1 SUMMARY AGENDA: CHAMBER 11.30am Prayers Afterwards Oral Questions: Justice 12.30pm Urgent Questions, Ministerial Statements (if any) Up to 20 minutes Ten Minute Rule Motion: DiGeorge Syndrome (Review and National Health Service Duty) (David Duguid) Up to three hours Emergency Debate: Sections 58 and 59 of the Offences Against the Person Act 1861 Until 7.00pm Non-Domestic Rating (Nursery Grounds) Bill: Second Reading Followed by Motion without separate debate: Programme Until 7.00pm General Debate: NATO No debate Statutory Instruments (Motions for approval) No debate after Digital Economy, Registration Service and Statistics and 7.00pm Registration (Motion) No debate Presentation of Public Petitions Until 7.30pm or for Adjournment Debate: Future of Princess Alexandra Hospital in half an hour Harlow (Robert Halfon) WESTMINSTER HALL 9.30am Polish anti-defamation law 11.00am Potholes and road maintenance (The sitting will be suspended from 11.30am to 2.30pm.) 2.30pm Public sector pay policy 4.00pm Conflict in South Sudan 4.30pm Proposed road alterations around Stonehenge 2 Tuesday 5 June 2018 OP No.144: Part 1 CONTENTS CONTENTS PART 1: BUSINESS TODAY 3 Chamber 8 Westminster Hall 9 Written Statements 10 Committees meeting today 14 Committee reports published today 15 Announcements 16 Further Information PART 2: FUTURE BUSINESS 18 A. Calendar of Business 41 B. Remaining Orders and Notices Notes: Item marked [R] indicates that a member has declared a relevant interest. Tuesday 5 June 2018 OP No.144: Part 1 BUSINESS Today: CHAMBER 3 BUSINESS TODAY: CHAMBER 11.30am Prayers Followed by QUESTIONS Oral Questions to the Secretary of State for Justice 1 Liz Saville Roberts (Dwyfor Meirionnydd) What assessment he has made of the potential merits of introducing a prison service parliamentary scheme. -

Inside Pages

The Parliamentary and Scientific Committee Annual Report 2010 THE PARLIAMENTARY AND SCIENTIFIC COMMITTEE (An Associate Parliamentary Group including Members of the Associate Parliamentary Engineering Group) Established 1939 The Parliamentary and Scientific Committee is a primary focus for scientific and technological issues providing a long-term liaison between Parliamentarians and scientific and engineering bodies, science-based industry, academia and organisations representing those significantly affected by science. The main aim is to focus on those issues where science and politics meet, informing Members of both Houses of Parliament by indicating the relevance of scientific and technological developments to matters of public interest and to the development of policy. The Committee meets once a month when Parliament is sitting to debate a scientific or engineering topic and its relationship with political issues. These debates take place in the Palace of Westminster, starting at 5.30pm and are usually followed by informal receptions. Attendance is typically 60 –80. Most debates are followed by a working dinner where the informal atmosphere facilitates open and wide-ranging discussion between interested Parliamentarians and those most closely concerned with the evening’s topic. The Committee arranges visits to industrial and scientific establishments. Typically a party of a dozen or so will include two or three Parliamentarians who will thereby have an in-depth introduction to some aspect of the real world of science and technology. Cover photograph Parliamentary copyright images are reproduced with the permission of Parliament. Foreword by the President The Rt Hon the Lord Jenkin of Roding The President’s Foreword to the Parliamentary and Scientific Committee Annual Report is an opportunity to reflect upon current issues and future opportunities. -

Annual Review Annex 2019-2020

Annex to the Annual Review 2019| 2020 2 Contents Fellows elected in 2019 . 2 Frontiers of Development seed funding grants . 36 International Fellows . 2 Leaders in Innovation Fellowships . 38 Honorary Fellow . .2 Global Challenges Research Fund Africa Catalyst . 44 Fellows . .2 Higher Education Partnerships in sub-Saharan Trustee Board . 4 Africa . 44 Academy Governance Committees . 5 Africa Prize for Engineering Innovation . 48 Academy Operating Committees . 8 Africa Prize for Engineering Innovation alumni grants programme 2019–2020 . 49 Awards 2019 . 11 Africa Prize: service delivery . 49 Grants, fellowships and programmes . .13 . Africa Prize: travel and training scheme . .49 Research Chairs . 13 Africa Prize: business grants . 50 Chairs in Emerging Technologies. .16 Engineering X . 50 Senior Research Fellowships . .17 Safer Complex Systems . .50 Leverhulme Trust Research Fellowships . .18 Safer End of Engineered Life . .51 Daphne Jackson Trust Fellowships. .18 Engineering Skills where they are most needed . 51 Research Fellowships . 19 Transforming Systems through Partnership . 53 Engineering for Development Research UK-China Urban Flooding Research Impact Fellowships . 22 programme . 58 Associate Research Fellowships. 22 Distinguished Visiting Fellowships and Missions UK Intelligence Community Postdoctoral in Turkey . 59 Research Fellowships . 23 Distinguished Visiting Fellowships . 60 Lloyd’s Register Foundation Research Global Grand Challenges Summit 2019 Fellowships . 23 Follow-up Programmes . 61 Industrial Fellowships Scheme . 24 Ingenious public engagement awards . 62 APEX awards . 26 Engineering Leaders Scholarships . 63 Regional Engagement Awards . 27 Visiting Professors. 67 Proof of Concept Awards . 27 Sainsbury Management Fellowships . 69 Enterprise Fellowships . 28 Connecting STEM teachers programme . 69 IRT Enterprise Fellowships . 28 Queen Elizabeth Prize for Engineering . 71 . ERA Award. 28 Panel of judges. -

RCUK REVIEW of E-SCIENCE in the UNITED KINGDOM

RCUK Review of e-Science 2009 Section 1 Information for the Panel Overview: Funding of Science and Innovation in the UK RCUK REVIEW OF e-SCIENCE IN THE UNITED KINGDOM EVIDENCE TO THE PANEL NOVEMBER 2009 Research Councils UK (RCUK) Polaris House, North Star Avenue Swindon, SN2 1ET Wiltshire, UK http://www.rcuk.ac.uk RCUK Review of e-Science 2009 Section 1 Information for the Panel Overview: Funding of Science and Innovation in the UK Contents 1. Preface and Summary 1.1 Table of acronyms 1.2 Review of e-Science evidence framework 2. Current UK Science and Innovation Policy and Research Funding Overview 2.1 Setting the scene 2.2 How funding for science is secured 2.3 Funding for research 3. An Introduction to e-Science Research in the UK 3.1 Overview 3.2 Background and introduction 3.3 Funding for e-Science research in the UK 3.4 Bibliometric evidence 3.5 International engagement 3.6 Support for people 3.7 Knowledge Transfer 3.8 Further related funding 4. The Institution Perspective 4.1 Invited institutions evidence 4.2 Other institutes evidence RCUK Review of e-Science 2009 Section 1 Information for the Panel Overview: Funding of Science and Innovation in the UK 1. Preface and Summary This document has been produced in preparation for the 2009 RCUK Review of e-Science. The review is being organised by EPSRC, on behalf of RCUK and aims to inform stakeholders about the quality and impact of the UK science base. The purpose of this document is to provide an overview of research in e-Science in the UK in terms of its people, funding, organisation and policy. -

International Review of Mathematics

International Review of Mathematical Sciences 5 –10 December 2010 Contents Executive Summary iv Table of Acronyms v Acknowledgements vi Foreword vii 1. Introduction and Background 1 1.1 Purpose and scope of the review 1 1.2 Structure of the review 1 1.3 Review Panel activities 2 1.4 Relevant external events 3 1.5 Evidence used by the Panel 3 1.5.1 Data used by the Panel 3 1.5.2 Evidence provided by site visits and panel members’ expertise 4 1.6 Overview of the Panel’s report 4 1.7 On names of individuals and lists of institutions 5 1.8 The International Panel 5 2. Findings and Recommendations 6 2.1 Findings 6 2.2 Broad recommendations 6 2.3 Field-specific recommendations – challenges and opportunities 7 3. Nature of the Mathematical Sciences 10 3.1 Unity 10 3.2 Abstraction and long time scales 10 3.3 Community structure and research needs 12 4. Excellence and Capability through Diversity 13 International Review of Mathematical Science i Contents 5. Subfields of the Mathematical Sciences 15 5.1 Algebra 15 5.2 Analysis 16 5.3 Combinatorics and discrete mathematics 17 5.4 Dynamical systems and complexity 17 5.5 Fluid mechanics 18 5.6 Geometry and topology 19 5.7 Logic and foundations 20 5.8 Mathematical physics 20 5.9 Number theory 21 5.10 Numerical analysis/scientific computing 21 5.11 Operational research 22 5.12 Probability 23 5.13 Statistics 24 6. Applications Connected with the Mathematical Sciences 26 6.1 Computational science and engineering 26 6.2 Financial mathematics 27 6.3 Materials science and engineering 27 6.4 Mathematical biology and medicine 28 7. -

KAVLI INSTITUTE for COSMOLOGY UNIVERSITY of CAMBRIDGE Professor George Efstathiou FRS, Director KICC

KAVLI INSTITUTE FOR COSMOLOGY UNIVERSITY Of CAMBRIDGE Professor George Efstathiou FRS, Director KICC MADINGLEY ROAD • CAMBRIDGE CB3 0HA • U.K. Professor Adrian Smith FRS, Telephone: +44 (0)1233 337530 BIS, Secretary: +44 (0)1223 337516 1 Victoria Street, email: [email protected] London, SW1H 0ET. July 19, 2010 Dear Professor Smith, Earlier this month a group of senior academics, including myself, submitted a petition to Professor Michael Sterling signed by nearly 1000 scientists expressing a loss of confidence in the CEO of STFC. In fact, there was widespread loss of confidence in STFC in 2008. However, the academic community did not express this in the form of a petition in the hope that the Wakeham Review and the RCUK Structural Review of STFC would lead to changes that might help to restore some confidence. Our group has met with Professor Sterling twice and we have had some constructive discus- sions. However, we have reached an impasse on aspects of the governance of STFC, particularly on the composition of STFC Council, which I believe is a critical issue. The composition of STFC Council is radically different to the composition of the other Research Councils. The composition of STFC Council was flagged as a major issue in the 2008 Science and Technology Select Committee Report and by the Wakeham Review. I quote from the Wakeham review: ‘The Panel was immediately drawn to the different governance structure that exists in STFC in comparison with other Research Councils, notably a reduced Council membership of 10 individuals, four of whom are not university-based academics, and a further three of whom are from the STFC executive. -

February 2008

THE LONDON MATHEMATICAL SOCIETY NEWSLETTER No. 367 February 2008 Society MATHEMATICS POLICY ROUND-UP Meetings In early January, Makhan Singh highly beneficial, and that the and Events took up his post as the new policy generally goes against the project manager for the more Leitch agenda on lifelong learn- 2008 maths grads project, exploring ing and skills. It said, “We would Friday 8 February ways of increasing the numbers suggest that national needs Mary Cartwright taking mathematics-related would be best met by regarding Lecture, Oxford undergraduate courses. Makhan a much greater number of part- [page 3] has a wealth of experience that time mathematics ELQ students Monday 31 March will help him to take the project as exempt (or at least eligible for Northern Regional forwards. In particular, he has val- some degree of support via a tar- Meeting, Manchester uable project management skills geted allocation) than just those [page 7] and has worked in other Widen- studying for a full (second) de- Friday 25 April ing Participation projects so he gree programme with substantial Women in has a full and practical apprecia- mathematical content. The sums Mathematics Day tion of what more maths grads involved would be very small as London [page 9] is aiming to achieve. Originally a proportion of the total math- training as an engineer, Makhan ematics spend, but would have a Monday 9 June has also spent time as a classroom substantial impact on take-up of Midlands Regional teacher. Makhan takes over from the opportunities for valuable re- Meeting, Birmingham Helen Orr who left the project in training and upskilling. -

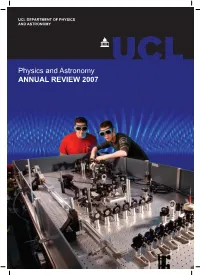

Physics and Astronomy ANNUAL REVIEW 2007 Contents

UCL DEPARTMENT OF PHYSICS AND ASTRONOMY Physics and Astronomy ANNUAL REVIEW 2007 Contents Introduction Page 1 Undergraduate and Postgraduate Students Page 2 Staff Highlights and News Page 5 Alumni Matters Page 7 Public Outreach Page 8 Obituary to Professor Mike Seaton Page 9 Careers with a Physics Degree Page 10 Research Groups: Astrophysics Page 12 Atomic, Molecular, Optical and Positron Physics Page 15 High Energy Physics Page 18 Condensed Matter and Materials Physics Page 20 Grants and Contracts Page 23 Publications Page 25 Staff Page 32 Cover image is a Joseph Wood (University College London) and Jarlath McKenna (Queen’s University Belfast) from the Ultrafast While every effort has been made to ensure the Physics UCL/QUB collaboration working on the hollow fibre chirped accuracy of the information in this document, the mirror pulse compressor at the Central Laser Facility (Rutherford Department cannot accept responsibility for any Appleton Laboratory).The ten femtosecond laser pulses generated errors or omissions contained herein. are used to create, image and control nuclear wavepackets in hydrogenic molecular systems. The trace in the A copy of this review and further details about the background of the page is an illustration of a vibrational revival department may be found on the website in deuterium ions, which have been modelled and experimental http://www.phys.ucl.ac.uk imaged by the collaboration. This work was recently published in Physical Review A. Edited by Kate Heyworth, if you have any comments or suggestions for the 2008 issue please contact Kate at [email protected] Introduction “UCL is booming”, so started the White Paper on Modernising UCL published by the Provost in Introduction Page 1 June.