Exhibition Guide

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Alberto Giacometti and the Crisis of the Monument, 1935–45 A

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Hollow Man: Alberto Giacometti and the Crisis of the Monument, 1935–45 A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Art History by Joanna Marie Fiduccia 2017 Ó Copyright by Joanna Marie Fiduccia 2017 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Hollow Man: Alberto Giacometti and the Crisis of the Monument, 1935–45 by Joanna Marie Fiduccia Doctor of Philosophy in Art History University of California, Los Angeles, 2017 Professor George Thomas Baker, Chair This dissertation presents the first extended analysis of Alberto Giacometti’s sculpture between 1935 and 1945. In 1935, Giacometti renounced his abstract Surrealist objects and began producing portrait busts and miniature figures, many no larger than an almond. Although they are conventionally dismissed as symptoms of a personal crisis, these works unfold a series of significant interventions into the conventions of figurative sculpture whose consequences persisted in Giacometti’s iconic postwar work. Those interventions — disrupting the harmonious relationship of surface to interior, the stable scale relations between the work and its viewer, and the unity and integrity of the sculptural body — developed from Giacometti’s Surrealist experiments in which the production of a form paradoxically entailed its aggressive unmaking. By thus bridging Giacometti’s pre- and postwar oeuvres, this decade-long interval merges two ii distinct accounts of twentieth-century sculpture, each of which claims its own version of Giacometti: a Surrealist artist probing sculpture’s ambivalent relationship to the everyday object, and an Existentialist sculptor invested in phenomenological experience. This project theorizes Giacometti’s artistic crisis as the collision of these two models, concentrated in his modest portrait busts and tiny figures. -

Maler Der Frühen Moderne 8. September 2017 Bis 28. Januar 2018

FERDINAND HODLER Maler der frhen Moderne 8. September 2017 bis 28. Januar 2018 Medienkonferenz: Donnerstag, 7. September 2017, 11 Uhr Inhalt 1. Allgemeine Informationen Seite 2 2. Informationen zur Ausstellung Seite 4 3. Biografie Ferdinand Hodler Seite 6 4. Wandtexte Seite 10 5. Publikation Seite 15 6. Rahmenprogramm zur Ausstellung (Auswahl) Seite 16 7. Laufende und kommende Ausstellungen Seite 23 Leiter Unternehmenskommunikation / Pressesprecher Sven Bergmann T +49 228 9171–204 F +49 228 9171–211 [email protected] Allgemeine Informationen Dauer 8. September 2017 bis 28. Januar 2018 Intendant Rein Wolfs Kaufmnnischer Geschftsfhrer Dr. Bernhard Spies Kuratorin Dr. Monika Brunner Ausstellungskuratorin Dr. Angelica Francke Leiter Unternehmenskommunikation / Sven Bergmann Pressesprecher Publikation / Presseexemplar 35 € / 17 € ffnungszeiten Dienstag und Mittwoch: 10 bis 21 Uhr Donnerstag bis Sonntag: 10 bis 19 Uhr Feiertags: 10 bis 19 Uhr Freitags fr angemeldete Gruppen und Schulklassen ab 9 Uhr geffnet Montags geschlossen Eintritt regulr / ermigt / Familienkarte 10 € / 6,50 € / 16 € Happy-Hour-Ticket 7 € fr alle Ausstellungen Dienstag und Mittwoch: 19 bis 21 Uhr Donnerstag bis Sonntag: 17 bis 19 Uhr (nur für Individualbesucher) ffentliche Turnusfhrungen Mittwochs: 18 Uhr Sonn- und feiertags: 14 Uhr 3 € / ermigt 1,50 €, zzgl. Eintritt Kinderfhrungen Sonn- und feiertags, 14 Uhr Teilnahme frei mit Eintrittskarte Audioguide 4 € / ermßigt 3 € Deutsch und Englisch Audiodeskription fr Blinde: 2 € Mediaguide in Gebrdensprache: 2 € Knstlerische Konzeption und Produktion des Audioguides durch Linon Verkehrsverbindungen U-Bahn-Linien 16, 63, 66 und Bus- Linien 610, 611 und 630 bis Heussallee / Museumsmeile Parkmglichkeiten Parkhaus Emil-Nolde-Strae Navigation: Emil-Nolde-Strae 11, 53113 Bonn Presseinformation (dt. / engl.) www.bundeskunsthalle.de/presse Informationen zum Programm T +49 228 9171–243 und Anmeldung zu F +49 228 9171–244 Gruppenfhrungen [email protected] Allgemeine Informationen (dt. -

250 Years Later: Swiss Art Takes Center Stage on the Day Christie’S Turns 250 5 December 2016

PRESS RELEASE | ZURICH FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE | 8 NOVEMBER 2016 250 YEARS LATER: SWISS ART TAKES CENTER STAGE ON THE DAY CHRISTIE’S TURNS 250 5 DECEMBER 2016 Zurich – Christie’s Zurich has the privilege to be one of the company’s two salerooms to stage an auction on the actual day that Christie’s turns 250. On 5 December 1766 James Christie, the founder of today’s world leading art business, held his first auction in London, offering an array of objects – from 4 irons to 4 Indian glass panels. Within a couple of months James Christie revolutionised the auction business by staging the first ever stand-alone painting auction on 20 March 1767. This tradition will continue on 5 December 2016, when Christie’s will present 80 works of Swiss Art – a category which has held stand-alone auctions for 25 years in Zurich. After setting a new world auction record for Le Corbusier (1887-1965) when selling the sculpture La Femme, for over CHF 3 million in Zurich two years ago, Hans-Peter Keller and his Swiss Art team are delighted to present Le Corbusier’s Ozon, Opus I, realized in 1947. Ozon, was the small village in the French Pyrenees, Le Corbusier and his wife moved to, when the Germans marched into Paris in 1940. Here, he continued to develop the form and lines of the female body and integrated the findings into his work – not only in his sculptures but also into his drawings, paintings and his architecture projects. Opus I is a clear reference to the organ Le Corbusier was most fascinated by, the human ear, which developed its own dynamism throughout the artist’s oeuvre (estimate: CHF 400,000- 600,000). -

Schweizerische Kunstausstellung Basel 1956

1 A 1 Schweizerische 7815 Kunstausstellung Basel 1956 H Bazaine-Bertholle-Bissière- Eble Abstrakte Maler Estève-Hartung-Lanskoy- Loutre Manessier-Le Moal-Nallard Reichel-Singier-Vieira da Silva Spiller-de Staël Ausstellung Juni, Juli Maîtres de l'art moderne Delacroix-Renoir-van Gogh Cézanne -Braque-Rouault Picasso etc. Ausstellung August, September, Oktober Illustrierte Kataloge Galerie Beyeler Basel/Bäumleingasse 9 täglich (sonntags nur 10-12 Uhr) ETHICS SIK Telephon 222558 02000001352510 Schweizerische Kunstausstellung Basel 1956 A/\ r- vf Schweizerisches Institut WlU . W für Kunstwissenschaft Zürich Schweizer Mustermesse, Halle 8, «Baslerhalle» 2. Juni bis 15. Juli 1956 (ö ö ~t s \~2-~ Dauer der Ausstellung 2. Juni bis 15. Juli 1956 Besuchszeiten Täglich 10-12 und 14-17 Uhr Sonntags durchgehend von 10-17 Uhr Eintrittspreise Einmaliger Eintritt (inkl. Billettsteuer) Fr. 1.50 Schüler und Studenten Fr.I.¬ Schüler in geführten Gruppen Fr.-.50 Tageskarte Fr. 2.50 Illustrierter Katalog Fr. 2.50 Verkäufe Alle Verkäufe haben durch Vermittlung der Kasse zu erfolgen. Fürdie ausdem Ausland eingesandten Werke hat der Käufer den Zoll zu tragen. Die Abgabe der gekauften Werke erfolgt nach Schluß der Ausstellung. Prof. Dr. Max Huggler, Bern, Präsident Walter Bodmer, Basel Serge Brignoni, Bern Charles Chinet, Rolle Charles-François Philippe, Genf Hans Stocker, Basel Frau Janebé, Boudry Frau Elsa Burckhardt-Blum, Küsnacht, Ersatz Max von Mühlenen, Bern, Ersatz Rudolf Zender, Winterthur, Ersatz Werner Bär, Zürich, Präsident Bruno Giacometti, Zürich Otto Charles Bänninger, Zürich Hermann Hubacher, Zürich Remo Rossi, Locarno Max Weber, Genf Fräulein Hildi Hess, Zürich Paul Baud, Genf, Ersatz Casimir Reymond, Lutry, Ersatz Fräulein Hedwig Frei, Basel, Ersatz Architektonische Gestaltung E. -

GÜNTER KONRAD Visual Artist Contents

GÜNTER KONRAD visual artist contents CURRICULUM VITAE 4 milestones FRAGMENTS GET A NEW CODE 7 artist statement EDITIONS 8 collector‘s edition market edition commissioned artwork GENERAL CATALOG 14 covert and discovered history 01 - 197 2011 - 2017 All content and pictures by © Günter Konrad 2017. Except photographs page 5 by Arne Müseler, 80,81 by Jacob Pritchard. All art historical pictures are under public domain. 2 3 curriculum vitae BORN: 1976 in Leoben, Austria EDUCATION: 2001 - 2005 Multi Media Art, FH Salzburg DEGREE: Magister (FH) for artistic and creative professions CURRENT: Lives and works in Salzburg as a freelance artist milestones 1999 First exhibition in Leoben (Schwammerlturm) 2001 Experiments with décollages and spray paintings 2002 Cut-outs and rip-it-ups (Décollage) of billboards 2005 Photographic documentation of décollages 2006 Overpaintings of décollages 2007 Photographic documentation of urban fragments 2008 Décollage on furniture and lighting 2009 Photographic documentation of tags and urban inscriptions 2010 Combining décollages and art historical paintings 2011 First exhibition "covert and discovert history" in Graz (exhibition hall) 2012 And ongoing exhibitions and pop-ups in Vienna, Munich, Stuttgart, | Pörtschach, Wels, Mondsee, Leoben, Augsburg, Nürnberg, 2015 Purchase collection Spallart 2016 And ongoing commissioned artworks in Graz, Munich, New York City, Salzburg, Serfaus, Singapore, Vienna, Zirl 2017 Stuttgart, Innsbruck, Linz, Vienna, Klagenfurt, Graz, Salzburg commissioned artworks in Berlin, Vienna, Tyrol, Obertauern, Wels 2018 Augsburg, Friedrichshafen, Innsbruck, Linz, Vienna, Klagenfurt, Graz, Salzburg, Obertauern, commissioned artworks in Linz, Graz, Vienna, Tyrol, OTHERS: Exhibition at MAK Vienna Digital stage design, Schauspielhaus Salzburg Videoscreenings in Leipzig, Vienna, Salzburg, Graz, Cologne, Feldkirch Interactive Theater Performances, Vienna (Brut) and Salzburg (Schauspielhaus), organizer of Punk/Garage/Wave concerts.. -

Expanding the Definition of Provenance: Adapting to Changes Since the Publication of the First AAM Guide Ot Provenance Research

The University of San Francisco USF Scholarship: a digital repository @ Gleeson Library | Geschke Center Master's Projects and Capstones Theses, Dissertations, Capstones and Projects Winter 12-15-2018 Expanding the Definition of Provenance: Adapting to Changes Since the Publication of the first AAM Guide ot Provenance Research Katlin Cunningham [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.usfca.edu/capstone Part of the Museum Studies Commons Recommended Citation Cunningham, Katlin, "Expanding the Definition of Provenance: Adapting to Changes Since the Publication of the first AAM Guide ot Provenance Research" (2018). Master's Projects and Capstones. 980. https://repository.usfca.edu/capstone/980 This Project/Capstone is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, Capstones and Projects at USF Scholarship: a digital repository @ Gleeson Library | Geschke Center. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Projects and Capstones by an authorized administrator of USF Scholarship: a digital repository @ Gleeson Library | Geschke Center. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Expanding the Definition of Provenance: Adapting to Changes Since the Publication of the first AAM Guide to Provenance Research Keywords: museum studies, provenance research, found in collections, technology, law, cultural biography by Katlin Cunningham Capstone project submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in Museum Studies Department of Art + Architecture University of San Francisco ________________________________________________________________________________ Faculty Advisor: Marjorie Schwarzer _________________________________________________________________________________ Academic Director: Paula Birnbaum December 14, 2018 Acknowledgements I would first like to thank my advisor Marjorie Schwarzer of the Museum Studies program at the University of San Francisco. -

PROGRAMME English the MAH CELEBRATES FERDINAND HODLER

PROGRAMME English THE MAH CELEBRATES FERDINAND HODLER 1853 : Born on 14 March in Bern The year 2018 marks the 100th anniversary of the death 1871: Arrives in Geneva, trained only as a vedutisto, or landscape painter of the painter Ferdinand Hodler, which occurred on 19 1872 : Meets Barthélemy Menn, his teacher at the May 1918 in his apartment on the Quai du Mont-Blanc School of Horology and Drawing in Geneva. The Museum of Art and History of Geneva, 1874 onwards : regularly participates in Swiss and international exhibitions and from 1875 wins which possesses around 150 of his paintings, a sculpture, a succession of prizes for his landscapes and historical paintings. Joins artistic and literary 800 drawings, notebooks and prints, as well as furniture Symbolist circles. that once belonged to the artist, are paying tribute to this 1889 : First purchase by the City of Geneva of a version of Miller, His Son and Donkey (1888) key figure in their collections, whose importance in the 1891: The display of The Night (1889-1890) history of modern art is constantly being demonstrated in is banned for reasons of obscenity by the Administrative Council, at the request of the mayor Switzerland and around the world. T. Turrettini. The painting was to enjoy great success when exhibited a few months later in Paris. 1897: Introduces the principles of parallelism during a lecture given in Fribourg This programme enables visitors to discover numerous 1904 : Guest of honour at the 19th Vienna Secession masterpieces by the painter, as well as unknown aspects 1917: Retrospective at the Kunsthaus in Zurich of his work and life, together with the historical and 1918 : Receives the title of Honorary Citizen of the artistic context in which he lived. -

Press Kit Lausanne, 15

Page 1 of 9 Press kit Lausanne, 15. October 2020 Giovanni Giacometti. Watercolors (16.10.2020 — 17.1.2021) Giovanni Giacometti Watercolors (16.10.2020 — 17.1.2021) Contents 1. Press release 2. Media images 3. Artist’s biography 4. Questions for the exhibition curators 5. Public engagement – Public outreach services 6. Museum services: Book- and Giftshop and Le Nabi Café-restaurant 7. MCBA partners and sponsors Contact Florence Dizdari Press coordinator 079 232 40 06 [email protected] Page 2 of 9 Press kit Lausanne, 15. October 2020 Giovanni Giacometti. Watercolors (16.10.2020 — 17.1.2021) 1. Press release MCBA the Musée cantonal des Beaux-Arts of Lausanne conserves many oil paintings and drawings by Giovanni Giacometti, a major artist from the turn of the 20th century and a faithful friend of one of the institution’s great donors, the Lausanne doctor Henri-Auguste Widmer. By putting on display an exceptional group of watercolors, all of them privately owned and almost all unknown outside their home, MCBA is inviting us to discover a lesser known side of Giovanni Giacometti’s remarkable body of work. Giovanni Giacometti (Stampa, 1868 – Glion, 1933) practiced watercolor throughout his life. As with his oil paintings, he found most of his subjects in the landscapes of his native region, Val Bregaglia and Engadin in the Canton of Graubünden. Still another source of inspiration were the members of his family going about their daily activities, as were local women and men busy working in the fields or fishing. The artist turned to watercolor for commissioned works as well. -

"Un Moderno Edificio Amministrativo" : Il Nuovo Complesso Architettonico Adibito a Uffici Dello Stato a Bellinzona

"Un moderno edificio amministrativo" : il nuovo complesso architettonico adibito a Uffici dello Stato a Bellinzona Autor(en): Cavadini, Nicoletta Ossanna Objekttyp: Article Zeitschrift: Kunst + Architektur in der Schweiz = Art + architecture en Suisse = Arte + architettura in Svizzera Band (Jahr): 58 (2007) Heft 1: Im Büro = Au bureau = In ufficio PDF erstellt am: 10.10.2021 Persistenter Link: http://doi.org/10.5169/seals-394356 Nutzungsbedingungen Die ETH-Bibliothek ist Anbieterin der digitalisierten Zeitschriften. Sie besitzt keine Urheberrechte an den Inhalten der Zeitschriften. Die Rechte liegen in der Regel bei den Herausgebern. Die auf der Plattform e-periodica veröffentlichten Dokumente stehen für nicht-kommerzielle Zwecke in Lehre und Forschung sowie für die private Nutzung frei zur Verfügung. Einzelne Dateien oder Ausdrucke aus diesem Angebot können zusammen mit diesen Nutzungsbedingungen und den korrekten Herkunftsbezeichnungen weitergegeben werden. Das Veröffentlichen von Bildern in Print- und Online-Publikationen ist nur mit vorheriger Genehmigung der Rechteinhaber erlaubt. Die systematische Speicherung von Teilen des elektronischen Angebots auf anderen Servern bedarf ebenfalls des schriftlichen Einverständnisses der Rechteinhaber. Haftungsausschluss Alle Angaben erfolgen ohne Gewähr für Vollständigkeit oder Richtigkeit. Es wird keine Haftung übernommen für Schäden durch die Verwendung von Informationen aus diesem Online-Angebot oder durch das Fehlen von Informationen. Dies gilt auch für Inhalte Dritter, die über dieses Angebot -

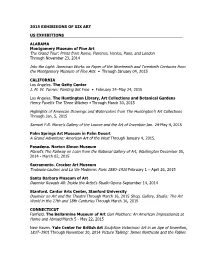

2015 Exhibitions of XIX ART

2015 EXHIBItiONS OF XIX ART US EXHIBITIONS ALABAMA Montgomery Museum of Fine Art The Grand Tour: Prints from Rome, Florence, Venice, Paris, and London Through November 23, 2014 Into the Light: American Works on Paper of the Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries from the Montgomery Museum of Fine Arts • Through January 04, 2015 CALIFORNIA Los Angeles. The Getty Center J. M. W. Turner: Painting Set Free • February 24–May 24, 2015 Los Angeles. The Huntington Library, Art Collections and Botanical Gardens Henry Fuseli’s The Three Witches • Through March 30, 2015 Highlights of American Drawings and Watercolors from The Huntington’s Art Collections Through Jan. 5, 2015 Samuel F.B. Morse’s Gallery of the Louvre and the Art of Invention Jan. 24-May 4, 2015 Palm Springs Art Museum in Palm Desert A Grand Adventure: American Art of the West Through January 4, 2015. Pasadena. Norton Simon Museum Manet's The Railway on Loan from the National Gallery of Art, Washington December 05, 2014 - March 02, 2015 Sacramento. Crocker Art Museum Toulouse-Lautrec and La Vie Moderne: Paris 1880–1910 February 1 – April 26, 2015 Santa Barbara Museum of Art Daumier Reveals All: Inside the Artist’s Studio Opens September 14, 2014 Stanford. Cantor Arts Center, Stanford University Daumier on Art and the Theatre Through March 16, 2015 Shop, Gallery, Studio: The Art World in the 17th and 18th Centuries Through March 16, 2015 CONNECTICUT Fairfield. The Bellarmine Museum of Art Gari Melchers: An American Impressionist at Home and Abroad March 5 - May 22, 2015 New Haven. Yale Center for British Art Sculpture Victorious: Art in an Age of Invention, 1837–1901 Through November 30, 2014 Picture Talking: James Northcote and the Fables Through December 14, 2014 Figures of Empire: Slavery and Portraiture in Eighteenth-Century Atlantic Britain Through December 14, 2014 DELAWARE Delaware Art Museum Oscar Wilde’s Salomé: Illustrating Death and Desire • February 7, 2015 - May 10, 2015 FLORIDA Gainesville. -

Surrealism Switzerland

Museo d’arte della Svizzera italiana Surrealism Switzerland Lugano +41(0)91 815 7971 10 February – 16 June 2019 [email protected] www.masilugano.ch Museo d’arte della Svizzera italiana, Lugano, at LAC Lugano Arte e Cultura Curated by Peter Fischer, art historian and independent curator and Julia Schallberger, assistant curator at Aargauer Kunsthaus Coordination and staging at MASI Lugano by Tobia Bezzola, director and Francesca Benini, assistant curator Press conference: Friday 8 February at 11:00 am Opening: Saturday 9 February at 6:00 pm Press release Lugano, Friday 8 February 2019 From 10 February to 16 June 2019, the Museo d’arte della Svizzera italiana presents a great retrospective regarding Swiss Surrealism, organised in cooperation with the Aargauer Kunsthaus. The exhibition, titled Surrealism Switzerland , investigates both the influence the movement had on Swiss art and the contribution of Swiss artists in defining it. These artists include Hans Arp, Alberto Giacometti, Paul Klee and Meret Oppenheim. Starting from the question “Does Swiss Surrealism actually exist?” the Museo d’arte della Svizzera italiana (MASI) and the Aargauer Kunsthaus thoroughly examine the issue of Surrealism in Switzerland, which is an important part of the art history of this Country. The two museums present a new great retrospective in two different settings. The first, in Aarau from 1 September 2018 to 2 January 2019, focused not only on historical Surrealism, but also on its influence on contemporary art. The second one, setting at MASI from 10 February to 16 June 2019, deals exclusively with the historical expressions of Surrealism until the end of the 1950s, and is curated by museum director Tobia Bezzola in cooperation with Francesca Bernini, assistant curator at MASI. -

The Life and Work of Ferdinand Hodler (1853- 1918)

The life and work of Ferdinand Hodler (1853- 1918) Autor(en): [s.n.] Objekttyp: Article Zeitschrift: The Swiss observer : the journal of the Federation of Swiss Societies in the UK Band (Jahr): - (1973) Heft 1660 PDF erstellt am: 27.09.2021 Persistenter Link: http://doi.org/10.5169/seals-689004 Nutzungsbedingungen Die ETH-Bibliothek ist Anbieterin der digitalisierten Zeitschriften. Sie besitzt keine Urheberrechte an den Inhalten der Zeitschriften. Die Rechte liegen in der Regel bei den Herausgebern. Die auf der Plattform e-periodica veröffentlichten Dokumente stehen für nicht-kommerzielle Zwecke in Lehre und Forschung sowie für die private Nutzung frei zur Verfügung. Einzelne Dateien oder Ausdrucke aus diesem Angebot können zusammen mit diesen Nutzungsbedingungen und den korrekten Herkunftsbezeichnungen weitergegeben werden. Das Veröffentlichen von Bildern in Print- und Online-Publikationen ist nur mit vorheriger Genehmigung der Rechteinhaber erlaubt. Die systematische Speicherung von Teilen des elektronischen Angebots auf anderen Servern bedarf ebenfalls des schriftlichen Einverständnisses der Rechteinhaber. Haftungsausschluss Alle Angaben erfolgen ohne Gewähr für Vollständigkeit oder Richtigkeit. Es wird keine Haftung übernommen für Schäden durch die Verwendung von Informationen aus diesem Online-Angebot oder durch das Fehlen von Informationen. Dies gilt auch für Inhalte Dritter, die über dieses Angebot zugänglich sind. Ein Dienst der ETH-Bibliothek ETH Zürich, Rämistrasse 101, 8092 Zürich, Schweiz, www.library.ethz.ch http://www.e-periodica.ch Che Swiss Obscrocr Founded in 1919 by Paul F. Boehringer The Official Organ of the Swiss Colony in Great Britain Vol.59 No. 1660 : FRIDAY, 11th MAY, 1973 THE LIFE AND WORKOF ^ FEFÖNAND HODLER (1853-1918) Hodler a few more.