Visitors Guide EN

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Maler Der Frühen Moderne 8. September 2017 Bis 28. Januar 2018

FERDINAND HODLER Maler der frhen Moderne 8. September 2017 bis 28. Januar 2018 Medienkonferenz: Donnerstag, 7. September 2017, 11 Uhr Inhalt 1. Allgemeine Informationen Seite 2 2. Informationen zur Ausstellung Seite 4 3. Biografie Ferdinand Hodler Seite 6 4. Wandtexte Seite 10 5. Publikation Seite 15 6. Rahmenprogramm zur Ausstellung (Auswahl) Seite 16 7. Laufende und kommende Ausstellungen Seite 23 Leiter Unternehmenskommunikation / Pressesprecher Sven Bergmann T +49 228 9171–204 F +49 228 9171–211 [email protected] Allgemeine Informationen Dauer 8. September 2017 bis 28. Januar 2018 Intendant Rein Wolfs Kaufmnnischer Geschftsfhrer Dr. Bernhard Spies Kuratorin Dr. Monika Brunner Ausstellungskuratorin Dr. Angelica Francke Leiter Unternehmenskommunikation / Sven Bergmann Pressesprecher Publikation / Presseexemplar 35 € / 17 € ffnungszeiten Dienstag und Mittwoch: 10 bis 21 Uhr Donnerstag bis Sonntag: 10 bis 19 Uhr Feiertags: 10 bis 19 Uhr Freitags fr angemeldete Gruppen und Schulklassen ab 9 Uhr geffnet Montags geschlossen Eintritt regulr / ermigt / Familienkarte 10 € / 6,50 € / 16 € Happy-Hour-Ticket 7 € fr alle Ausstellungen Dienstag und Mittwoch: 19 bis 21 Uhr Donnerstag bis Sonntag: 17 bis 19 Uhr (nur für Individualbesucher) ffentliche Turnusfhrungen Mittwochs: 18 Uhr Sonn- und feiertags: 14 Uhr 3 € / ermigt 1,50 €, zzgl. Eintritt Kinderfhrungen Sonn- und feiertags, 14 Uhr Teilnahme frei mit Eintrittskarte Audioguide 4 € / ermßigt 3 € Deutsch und Englisch Audiodeskription fr Blinde: 2 € Mediaguide in Gebrdensprache: 2 € Knstlerische Konzeption und Produktion des Audioguides durch Linon Verkehrsverbindungen U-Bahn-Linien 16, 63, 66 und Bus- Linien 610, 611 und 630 bis Heussallee / Museumsmeile Parkmglichkeiten Parkhaus Emil-Nolde-Strae Navigation: Emil-Nolde-Strae 11, 53113 Bonn Presseinformation (dt. / engl.) www.bundeskunsthalle.de/presse Informationen zum Programm T +49 228 9171–243 und Anmeldung zu F +49 228 9171–244 Gruppenfhrungen [email protected] Allgemeine Informationen (dt. -

250 Years Later: Swiss Art Takes Center Stage on the Day Christie’S Turns 250 5 December 2016

PRESS RELEASE | ZURICH FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE | 8 NOVEMBER 2016 250 YEARS LATER: SWISS ART TAKES CENTER STAGE ON THE DAY CHRISTIE’S TURNS 250 5 DECEMBER 2016 Zurich – Christie’s Zurich has the privilege to be one of the company’s two salerooms to stage an auction on the actual day that Christie’s turns 250. On 5 December 1766 James Christie, the founder of today’s world leading art business, held his first auction in London, offering an array of objects – from 4 irons to 4 Indian glass panels. Within a couple of months James Christie revolutionised the auction business by staging the first ever stand-alone painting auction on 20 March 1767. This tradition will continue on 5 December 2016, when Christie’s will present 80 works of Swiss Art – a category which has held stand-alone auctions for 25 years in Zurich. After setting a new world auction record for Le Corbusier (1887-1965) when selling the sculpture La Femme, for over CHF 3 million in Zurich two years ago, Hans-Peter Keller and his Swiss Art team are delighted to present Le Corbusier’s Ozon, Opus I, realized in 1947. Ozon, was the small village in the French Pyrenees, Le Corbusier and his wife moved to, when the Germans marched into Paris in 1940. Here, he continued to develop the form and lines of the female body and integrated the findings into his work – not only in his sculptures but also into his drawings, paintings and his architecture projects. Opus I is a clear reference to the organ Le Corbusier was most fascinated by, the human ear, which developed its own dynamism throughout the artist’s oeuvre (estimate: CHF 400,000- 600,000). -

Gce History of Art Major Modern Art Movements

FACTFILE: GCE HISTORY OF ART MAJOR MODERN ART MOVEMENTS Major Modern Art Movements Key words Overview New types of art; collage, assemblage, kinetic, The range of Major Modern Art Movements is photography, land art, earthworks, performance art. extensive. There are over 100 known art movements and information on a selected range of the better Use of new materials; found objects, ephemeral known art movements in modern times is provided materials, junk, readymades and everyday items. below. The influence of one art movement upon Expressive use of colour particularly in; another can be seen in the definitions as twentieth Impressionism, Post Impressionism, Fauvism, century art which became known as a time of ‘isms’. Cubism, Expressionism, and colour field painting. New Techniques; Pointilism, automatic drawing, frottage, action painting, Pop Art, Neo-Impressionism, Synthesism, Kinetic Art, Neo-Dada and Op Art. 1 FACTFILE: GCE HISTORY OF ART / MAJOR MODERN ART MOVEMENTS The Making of Modern Art The Nine most influential Art Movements to impact Cubism (fl. 1908–14) on Modern Art; Primarily practised in painting and originating (1) Impressionism; in Paris c.1907, Cubism saw artists employing (2) Fauvism; an analytic vision based on fragmentation and multiple viewpoints. It was like a deconstructing of (3) Cubism; the subject and came as a rejection of Renaissance- (4) Futurism; inspired linear perspective and rounded volumes. The two main artists practising Cubism were Pablo (5) Expressionism; Picasso and Georges Braque, in two variants (6) Dada; ‘Analytical Cubism’ and ‘Synthetic Cubism’. This movement was to influence abstract art for the (7) Surrealism; next 50 years with the emergence of the flat (8) Abstract Expressionism; picture plane and an alternative to conventional perspective. -

GÜNTER KONRAD Visual Artist Contents

GÜNTER KONRAD visual artist contents CURRICULUM VITAE 4 milestones FRAGMENTS GET A NEW CODE 7 artist statement EDITIONS 8 collector‘s edition market edition commissioned artwork GENERAL CATALOG 14 covert and discovered history 01 - 197 2011 - 2017 All content and pictures by © Günter Konrad 2017. Except photographs page 5 by Arne Müseler, 80,81 by Jacob Pritchard. All art historical pictures are under public domain. 2 3 curriculum vitae BORN: 1976 in Leoben, Austria EDUCATION: 2001 - 2005 Multi Media Art, FH Salzburg DEGREE: Magister (FH) for artistic and creative professions CURRENT: Lives and works in Salzburg as a freelance artist milestones 1999 First exhibition in Leoben (Schwammerlturm) 2001 Experiments with décollages and spray paintings 2002 Cut-outs and rip-it-ups (Décollage) of billboards 2005 Photographic documentation of décollages 2006 Overpaintings of décollages 2007 Photographic documentation of urban fragments 2008 Décollage on furniture and lighting 2009 Photographic documentation of tags and urban inscriptions 2010 Combining décollages and art historical paintings 2011 First exhibition "covert and discovert history" in Graz (exhibition hall) 2012 And ongoing exhibitions and pop-ups in Vienna, Munich, Stuttgart, | Pörtschach, Wels, Mondsee, Leoben, Augsburg, Nürnberg, 2015 Purchase collection Spallart 2016 And ongoing commissioned artworks in Graz, Munich, New York City, Salzburg, Serfaus, Singapore, Vienna, Zirl 2017 Stuttgart, Innsbruck, Linz, Vienna, Klagenfurt, Graz, Salzburg commissioned artworks in Berlin, Vienna, Tyrol, Obertauern, Wels 2018 Augsburg, Friedrichshafen, Innsbruck, Linz, Vienna, Klagenfurt, Graz, Salzburg, Obertauern, commissioned artworks in Linz, Graz, Vienna, Tyrol, OTHERS: Exhibition at MAK Vienna Digital stage design, Schauspielhaus Salzburg Videoscreenings in Leipzig, Vienna, Salzburg, Graz, Cologne, Feldkirch Interactive Theater Performances, Vienna (Brut) and Salzburg (Schauspielhaus), organizer of Punk/Garage/Wave concerts.. -

PROGRAMME English the MAH CELEBRATES FERDINAND HODLER

PROGRAMME English THE MAH CELEBRATES FERDINAND HODLER 1853 : Born on 14 March in Bern The year 2018 marks the 100th anniversary of the death 1871: Arrives in Geneva, trained only as a vedutisto, or landscape painter of the painter Ferdinand Hodler, which occurred on 19 1872 : Meets Barthélemy Menn, his teacher at the May 1918 in his apartment on the Quai du Mont-Blanc School of Horology and Drawing in Geneva. The Museum of Art and History of Geneva, 1874 onwards : regularly participates in Swiss and international exhibitions and from 1875 wins which possesses around 150 of his paintings, a sculpture, a succession of prizes for his landscapes and historical paintings. Joins artistic and literary 800 drawings, notebooks and prints, as well as furniture Symbolist circles. that once belonged to the artist, are paying tribute to this 1889 : First purchase by the City of Geneva of a version of Miller, His Son and Donkey (1888) key figure in their collections, whose importance in the 1891: The display of The Night (1889-1890) history of modern art is constantly being demonstrated in is banned for reasons of obscenity by the Administrative Council, at the request of the mayor Switzerland and around the world. T. Turrettini. The painting was to enjoy great success when exhibited a few months later in Paris. 1897: Introduces the principles of parallelism during a lecture given in Fribourg This programme enables visitors to discover numerous 1904 : Guest of honour at the 19th Vienna Secession masterpieces by the painter, as well as unknown aspects 1917: Retrospective at the Kunsthaus in Zurich of his work and life, together with the historical and 1918 : Receives the title of Honorary Citizen of the artistic context in which he lived. -

Press Kit Lausanne, 15

Page 1 of 9 Press kit Lausanne, 15. October 2020 Giovanni Giacometti. Watercolors (16.10.2020 — 17.1.2021) Giovanni Giacometti Watercolors (16.10.2020 — 17.1.2021) Contents 1. Press release 2. Media images 3. Artist’s biography 4. Questions for the exhibition curators 5. Public engagement – Public outreach services 6. Museum services: Book- and Giftshop and Le Nabi Café-restaurant 7. MCBA partners and sponsors Contact Florence Dizdari Press coordinator 079 232 40 06 [email protected] Page 2 of 9 Press kit Lausanne, 15. October 2020 Giovanni Giacometti. Watercolors (16.10.2020 — 17.1.2021) 1. Press release MCBA the Musée cantonal des Beaux-Arts of Lausanne conserves many oil paintings and drawings by Giovanni Giacometti, a major artist from the turn of the 20th century and a faithful friend of one of the institution’s great donors, the Lausanne doctor Henri-Auguste Widmer. By putting on display an exceptional group of watercolors, all of them privately owned and almost all unknown outside their home, MCBA is inviting us to discover a lesser known side of Giovanni Giacometti’s remarkable body of work. Giovanni Giacometti (Stampa, 1868 – Glion, 1933) practiced watercolor throughout his life. As with his oil paintings, he found most of his subjects in the landscapes of his native region, Val Bregaglia and Engadin in the Canton of Graubünden. Still another source of inspiration were the members of his family going about their daily activities, as were local women and men busy working in the fields or fishing. The artist turned to watercolor for commissioned works as well. -

RESEARCH DEGREES with PLYMOUTH UNIVERSITY Gold Griot

University of Plymouth PEARL https://pearl.plymouth.ac.uk 04 University of Plymouth Research Theses 01 Research Theses Main Collection 2018 Gold Griot: Jean-Michel Basquiat Telling (His) Story in Art Ross, Lucinda http://hdl.handle.net/10026.1/11135 University of Plymouth All content in PEARL is protected by copyright law. Author manuscripts are made available in accordance with publisher policies. Please cite only the published version using the details provided on the item record or document. In the absence of an open licence (e.g. Creative Commons), permissions for further reuse of content should be sought from the publisher or author. RESEARCH DEGREES WITH PLYMOUTH UNIVERSITY Gold Griot: Jean-Michel Basquiat Telling (His) Story in Art by Lucinda Ross A thesis submitted to Plymouth University In partial fulfilment for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Humanities and Performing Arts Doctoral Training Centre May 2017 Gold Griot: Jean-Michel Basquiat Telling (His) Story in Art Lucinda Ross Basquiat, Gold Griot, 1984 This copy of the thesis has been supplied on condition that anyone who consults it is understood to recognise that its copyright rests with the author and that no quotation from the thesis and no information derived from it may be published without the author’s prior consent. Gold Griot: Jean-Michel Basquiat Telling (His) Story in Art Lucinda Ross Abstract Emerging from an early association with street art during the 1980s, the artist Jean-Michel Basquiat was largely regarded within the New York avant-garde, as ‘an exotic other,’ a token Black artist in the world of American modern art; a perception which forced him to examine and seek to define his sense of identity within art and within society. -

2015 Exhibitions of XIX ART

2015 EXHIBItiONS OF XIX ART US EXHIBITIONS ALABAMA Montgomery Museum of Fine Art The Grand Tour: Prints from Rome, Florence, Venice, Paris, and London Through November 23, 2014 Into the Light: American Works on Paper of the Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries from the Montgomery Museum of Fine Arts • Through January 04, 2015 CALIFORNIA Los Angeles. The Getty Center J. M. W. Turner: Painting Set Free • February 24–May 24, 2015 Los Angeles. The Huntington Library, Art Collections and Botanical Gardens Henry Fuseli’s The Three Witches • Through March 30, 2015 Highlights of American Drawings and Watercolors from The Huntington’s Art Collections Through Jan. 5, 2015 Samuel F.B. Morse’s Gallery of the Louvre and the Art of Invention Jan. 24-May 4, 2015 Palm Springs Art Museum in Palm Desert A Grand Adventure: American Art of the West Through January 4, 2015. Pasadena. Norton Simon Museum Manet's The Railway on Loan from the National Gallery of Art, Washington December 05, 2014 - March 02, 2015 Sacramento. Crocker Art Museum Toulouse-Lautrec and La Vie Moderne: Paris 1880–1910 February 1 – April 26, 2015 Santa Barbara Museum of Art Daumier Reveals All: Inside the Artist’s Studio Opens September 14, 2014 Stanford. Cantor Arts Center, Stanford University Daumier on Art and the Theatre Through March 16, 2015 Shop, Gallery, Studio: The Art World in the 17th and 18th Centuries Through March 16, 2015 CONNECTICUT Fairfield. The Bellarmine Museum of Art Gari Melchers: An American Impressionist at Home and Abroad March 5 - May 22, 2015 New Haven. Yale Center for British Art Sculpture Victorious: Art in an Age of Invention, 1837–1901 Through November 30, 2014 Picture Talking: James Northcote and the Fables Through December 14, 2014 Figures of Empire: Slavery and Portraiture in Eighteenth-Century Atlantic Britain Through December 14, 2014 DELAWARE Delaware Art Museum Oscar Wilde’s Salomé: Illustrating Death and Desire • February 7, 2015 - May 10, 2015 FLORIDA Gainesville. -

1 Tseng Kwong

Tseng Kwong Chi Born in Hong Kong, 1950. Left Hong Kong with family in 1966. Educated in Hong Kong; Vancouver, Canada; Montreal, Canada; Paris, France. Settled in New York City, New York 1979. Died in New York City, New York 1990. EDUCATION L' École Superior d’Arts Graphiques at L’Academie Julien, Paris, France Sir George Williams University, Montreal, Canada University of British Columbia, Vancouver, Canada SOLO EXHIBITIONS 2010 “Tseng Kwong Chi: Body Painting with Keith Haring and Bill T. Jones,” Paul Kasmin Gallery, New York, NY, February 11 – March 27, 2010 2008-09 "Tseng Kwong Chi," Heather James Fine Art Gallery, Palm Springs, CA, October 16, 2008 – January 2009 2008 “Tseng Kwong Chi: Self-Portraits 1979-1989,” Ben Brown Fine Arts, London, UK, April 15 – May 31, 2008 (catalogue) “Tseng Kwong Chi: Self-Portraits 1979-1989,” Paul Kasmin Gallery, New York, NY, April 3 – May 3, 2008, (catalogue) 2007 “Tseng Kwong Chi: Ambiguous Ambassador,” Bernard Toale Gallery, Boston, MA, August 29 – September 29, 2007 2005-06 “Tseng Kwong Chi: East Meets West,” Galleria Carla Sozzani, Milan, Italy, December 14, 2005 – January 15, 2006 2005 “Tseng Kwong Chi: Ambiguous Ambassador,” Stephen Cohen Gallery, Los Angeles, CA 2004 “Tseng Kwong Chi: Ambiguous Ambassador,” Hanart Gallery, Hong Kong, September 17 – October 6, 2004 2003 "Tseng Kwong Chi: East Meets West," Lee Ka-Sing Gallery, Toronto, Canada 2002 "Tseng Kwong Chi: Ambiguous Ambassador," Chambers Fine Art, New York, NY "Tseng Kwong Chi: A Retrospective, " Philadelphia Art Alliance, Philadelphia, -

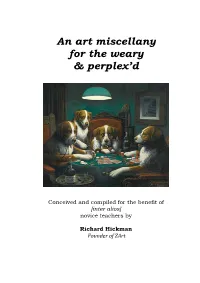

An Art Miscellany for the Weary & Perplex'd. Corsham

An art miscellany for the weary & perplex’d Conceived and compiled for the benefit of [inter alios] novice teachers by Richard Hickman Founder of ZArt ii For Anastasia, Alexi.... and Max Cover: Poker Game Oil on canvas 61cm X 86cm Cassius Marcellus Coolidge (1894) Retrieved from Wikimedia Commons [http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/] Frontispiece: (My Shirt is Alive With) Several Clambering Doggies of Inappropriate Hue. Acrylic on board 60cm X 90cm Richard Hickman (1994) [From the collection of Susan Hickman Pinder] iii An art miscellany for the weary & perplex’d First published by NSEAD [www.nsead.org] ISBN: 978-0-904684-34-6 This edition published by Barking Publications, Midsummer Common, Cambridge. © Richard Hickman 2018 iv Contents Acknowledgements vi Preface vii Part I: Hickman's Art Miscellany Introductory notes on the nature of art 1 DAMP HEMs 3 Notes on some styles of western art 8 Glossary of art-related terms 22 Money issues 45 Miscellaneous art facts 48 Looking at art objects 53 Studio techniques, materials and media 55 Hints for the traveller 65 Colours, countries, cultures and contexts 67 Colours used by artists 75 Art movements and periods 91 Recent art movements 94 World cultures having distinctive art forms 96 List of metaphorical and descriptive words 106 Part II: Art, creativity, & education: a canine perspective Introductory remarks 114 The nature of art 112 Creativity (1) 117 Art and the arts 134 Education Issues pertaining to classification 140 Creativity (2) 144 Culture 149 Selected aphorisms from Max 'the visionary' dog 156 Part III: Concluding observations The tail end 157 Bibliography 159 Appendix I 164 v Illustrations Cover: Poker Game, Cassius Coolidge (1894) Frontispiece: (My Shirt is Alive With) Several Clambering Doggies of Inappropriate Hue, Richard Hickman (1994) ii The Haywain, John Constable (1821) 3 Vagveg, Tabitha Millett (2013) 5 Series 1, No. -

The Life and Work of Ferdinand Hodler (1853- 1918)

The life and work of Ferdinand Hodler (1853- 1918) Autor(en): [s.n.] Objekttyp: Article Zeitschrift: The Swiss observer : the journal of the Federation of Swiss Societies in the UK Band (Jahr): - (1973) Heft 1660 PDF erstellt am: 27.09.2021 Persistenter Link: http://doi.org/10.5169/seals-689004 Nutzungsbedingungen Die ETH-Bibliothek ist Anbieterin der digitalisierten Zeitschriften. Sie besitzt keine Urheberrechte an den Inhalten der Zeitschriften. Die Rechte liegen in der Regel bei den Herausgebern. Die auf der Plattform e-periodica veröffentlichten Dokumente stehen für nicht-kommerzielle Zwecke in Lehre und Forschung sowie für die private Nutzung frei zur Verfügung. Einzelne Dateien oder Ausdrucke aus diesem Angebot können zusammen mit diesen Nutzungsbedingungen und den korrekten Herkunftsbezeichnungen weitergegeben werden. Das Veröffentlichen von Bildern in Print- und Online-Publikationen ist nur mit vorheriger Genehmigung der Rechteinhaber erlaubt. Die systematische Speicherung von Teilen des elektronischen Angebots auf anderen Servern bedarf ebenfalls des schriftlichen Einverständnisses der Rechteinhaber. Haftungsausschluss Alle Angaben erfolgen ohne Gewähr für Vollständigkeit oder Richtigkeit. Es wird keine Haftung übernommen für Schäden durch die Verwendung von Informationen aus diesem Online-Angebot oder durch das Fehlen von Informationen. Dies gilt auch für Inhalte Dritter, die über dieses Angebot zugänglich sind. Ein Dienst der ETH-Bibliothek ETH Zürich, Rämistrasse 101, 8092 Zürich, Schweiz, www.library.ethz.ch http://www.e-periodica.ch Che Swiss Obscrocr Founded in 1919 by Paul F. Boehringer The Official Organ of the Swiss Colony in Great Britain Vol.59 No. 1660 : FRIDAY, 11th MAY, 1973 THE LIFE AND WORKOF ^ FEFÖNAND HODLER (1853-1918) Hodler a few more. -

Early Modern Artist 8 September 2017 to 28 January 2018

FERDINAND HODLER Early Modern Artist 8 September 2017 to 28 January 2018 Media Conference: 7 September 2017, 11 a.m. Content 1. Exhibition Dates Page 2 2. Information on the Exhibition Page 4 3. Biography Ferdinand Hodler Page 6 4. Wall quotations Page 10 5. Publication Page 15 6. Current and Upcoming Exhibitions Page 16 Head of Corporate Communications / Press Officer Sven Bergmann T +49 228 9171–204 F +49 228 9171–211 [email protected] Exhibition Dates Exhibition 8 September 2017 to 28 January 2018 Director Rein Wolfs Managing Director Dr. Bernhard Spies Curator Dr. Monika Brunner Exhibition Curator Dr. Angelica Francke Head of Corporate Communications / Sven Bergmann Press Officer Catalogue / Press Copy € 35 / € 17 Opening Hours Tuesday and Wednesday: 10 a.m. to 9 p.m. Thursday to Sunday: 10 a.m. to 7 p.m. Public Holidays: 10 a.m. to 7 p.m. Closed on Mondays Admission standard / reduced / family ticket € 10 / € 6.50 / € 16 Happy Hour-Ticket € 7 Tuesday and Wednesday: 7 to 9 p.m. Thursday to Sunday: 5 to 7 p.m. (for individuals only) Guided Group Tours information T +49 228 9171–243 and registration F +49 228 9171–244 [email protected] Public Transport Underground lines 16, 63, 66 and bus lines 610, 611 and 630 to Heussallee / Museumsmeile. Parking There is a car and coach park on Emil- Nolde-Strae behind the Bundeskunsthalle. Navigation: Emil-Nolde-Strae 11, 53113 Bonn Press Information (German / English) www.bundeskunsthalle.de For press files follow ‘press’. General Information T +49 228 9171–200 (German / English) www.bundeskunsthalle.de An exhibition of the Bundeskunsthalle in cooperation with Kunstmuseum Bern Supported by Media Partner Supported by Cultural Partner Information on the Exhibition Ferdinand Hodler (1853-1918) is one of the most successful Swiss artists of the late 19th and early 20th century and was perceived as one of the most important painters of modernism by his contemporaries.