Jules Engel Oral History Transcript

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

UPA : Redesigning Animation

This document is downloaded from DR‑NTU (https://dr.ntu.edu.sg) Nanyang Technological University, Singapore. UPA : redesigning animation Bottini, Cinzia 2016 Bottini, C. (2016). UPA : redesigning animation. Doctoral thesis, Nanyang Technological University, Singapore. https://hdl.handle.net/10356/69065 https://doi.org/10.32657/10356/69065 Downloaded on 05 Oct 2021 20:18:45 SGT UPA: REDESIGNING ANIMATION CINZIA BOTTINI SCHOOL OF ART, DESIGN AND MEDIA 2016 UPA: REDESIGNING ANIMATION CINZIA BOTTINI School of Art, Design and Media A thesis submitted to the Nanyang Technological University in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy 2016 “Art does not reproduce the visible; rather, it makes visible.” Paul Klee, “Creative Credo” Acknowledgments When I started my doctoral studies, I could never have imagined what a formative learning experience it would be, both professionally and personally. I owe many people a debt of gratitude for all their help throughout this long journey. I deeply thank my supervisor, Professor Heitor Capuzzo; my cosupervisor, Giannalberto Bendazzi; and Professor Vibeke Sorensen, chair of the School of Art, Design and Media at Nanyang Technological University, Singapore for showing sincere compassion and offering unwavering moral support during a personally difficult stage of this Ph.D. I am also grateful for all their suggestions, critiques and observations that guided me in this research project, as well as their dedication and patience. My gratitude goes to Tee Bosustow, who graciously -

The University of Chicago Looking at Cartoons

THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO LOOKING AT CARTOONS: THE ART, LABOR, AND TECHNOLOGY OF AMERICAN CEL ANIMATION A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE DIVISION OF THE HUMANITIES IN CANDIDACY FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY DEPARTMENT OF CINEMA AND MEDIA STUDIES BY HANNAH MAITLAND FRANK CHICAGO, ILLINOIS AUGUST 2016 FOR MY FAMILY IN MEMORY OF MY FATHER Apparently he had examined them patiently picture by picture and imagined that they would be screened in the same way, failing at that time to grasp the principle of the cinematograph. —Flann O’Brien CONTENTS LIST OF FIGURES...............................................................................................................................v ABSTRACT.......................................................................................................................................vii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS....................................................................................................................viii INTRODUCTION LOOKING AT LABOR......................................................................................1 CHAPTER 1 ANIMATION AND MONTAGE; or, Photographic Records of Documents...................................................22 CHAPTER 2 A VIEW OF THE WORLD Toward a Photographic Theory of Cel Animation ...................................72 CHAPTER 3 PARS PRO TOTO Character Animation and the Work of the Anonymous Artist................121 CHAPTER 4 THE MULTIPLICATION OF TRACES Xerographic Reproduction and One Hundred and One Dalmatians.......174 -

Apéro Catalogue

APÉRO CATALOGUE Fine Art Collection Emotion July 2018 Bette Ridgeway APÉRO CATALOGUE Created by APERO, Inc. Curated by E.E. Jacks Designed by Jeremy E. Grayson Orange County, California, USA Copyright © 2018 APERO, Inc. All rights reserved. Emotion July 2018 ‘Emotion’ is a catalogue of art that focuses on moods, relationships and feelings. These emotive aspects have been incorporated into the subject matter. The work is comprised of drawings, paintings, sculpture, photography, mixed media, and digital pieces, both representational and abstract in nature. Ekaterina Adelskaya Emoveo, 2018 Ink On Paper 210 x 297 mm $200 Ekaterina Adelskaya Moscow, Moscow, Russia 792-6610-6101 [email protected] https://adelskaya.crevado.com/ Ekaterina Adelskaya Biography: Ekaterina Adelskaya is a multimedia artist from Moscow, Russia. In 2016 her love for contemporary art and the desire to develop art skills helped her to enter the Fine Art course at British Higher School of Art&Design / University of Hertfordshire in Moscow. Nowadays, she is focused on her art practice that explores the materialization of emotions. The nature, psychology and anatomy are her main sources of inspiration. APÉRO Catalogue Emotion - July 2018 2 Norma Alonzo Blue Moment, 2016 Acrylic On Paper 22 x 30 in $1,650 Norma Alonzo Santa Fe, New Mexico, USA 505-982-7447 [email protected] http://normaalonzo.com Norma Alonzo Biography: Norma Alonzo has always taken her painting life seriously, albeit privately. An extraordinarily accomplished artist, she has been painting for over 25 years. Beginning as a landscape painter, she quickly transitioned to an immersion in all genres to experiment and learn. -

Jules Langsner Papers, 1941-1967

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt5v19r00h No online items Finding Aid for the Jules Langsner papers, 1941-1967 Processed by UCLA Library Special Collections staff; machine-readable finding aid created by Caroline Cubé. UCLA Library Special Collections Room A1713, Charles E. Young Research Library Box 951575 Los Angeles, CA 90095-1575 Email: [email protected] URL: http://www.library.ucla.edu/libraries/special/scweb/ © 2007 The Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. Finding Aid for the Jules Langsner 1748 1 papers, 1941-1967 Descriptive Summary Title: Jules Langsner papers Date (inclusive): 1941-1967 Collection number: 1748 Creator: Jules Langsner, 1911-1967. Extent: 26 boxes (13 linear feet)1 oversize box. Abstract: Jules Langsner was born on May 5, 1911, in New York, New York and died in Los Angeles, California, on September 29, 1967. Langsner was surrounded by intellectuals and artists from a young age, and became a celebrated art writer, critic and curator. The collection consists of correspondence, manuscripts, ephemera, and photographs related to Langsner's writing, research and curatorial work. Language: English Repository: University of California, Los Angeles. Library Special Collections. Los Angeles, California 90095-1575 Physical location: Stored off-site at SRLF. Advance notice is required for access to the collection. Please contact the UCLA Library Special Collections Reference Desk for paging information. Restrictions on Access COLLECTION STORED OFF-SITE AT SRLF: Open for research. Advance notice required for access. Contact the UCLA Library Special Collections Reference Desk for paging information. Restrictions on Use and Reproduction Property rights to the physical object belong to the UCLA Library Special Collections. -

Press Release

Press Release www.webofstories.com London, UK – December 2nd 2011 Monday 5th December marks the 110th birthday of the late Walter Elias 'Walt' Disney, the American film producer, animator and co-founder of the Walt Disney Company. Web of Stories is proud to present a video recording of the life story of one of Walt Disney's most talented animators, Mr Jules Engel. Here, he talks about his time at Disney, co-founding the United Productions of America (UPA) studio, and Format Films where he produced Mr Magoo and the popular US series The Alvin Show and The Lone Ranger. In 1938, Jules Engel was asked by Walt Disney to work with them on what became the much-loved Disney classic, Fantasia. He was appointed the task of storyboarding the final dance sequences of the Russian sprites and Chinese mushrooms to the music of Tchaikovsky's Nutcracker Suite. Engel's passion for dance and art made him the perfect candidate to choreograph the sequences. Although much controversy still surrounds the fact that Jules Engel was never credited for his work on these sequences, here he describes what it was like working for the Walt Disney Company and meeting Walt Disney himself. "I remember first time I bumped into him and I said, 'Mr Disney, how do you...' He said, 'No, it's Walt.' Well, that's nice, you know, 'Okay Walt.' But the point is that he lived, he ate, he drank, whatever else there is about animation, that was his gut. He was not even a real person, he was so involved with that world. -

Helen Jones Carter, a Former Sculptor and Wife of the Composer Elliott

Pierre Restany, 72, an influential French art critic perhaps best known for championing artists such as Uves Klein, Christo, Aman and Jean Tinguely, died of heart failure on Helen Jones Carter, a former sculptor and wife of the 29 May in Paris. He coined the term "Nouveau Realisme" composer Elliott Carter, died in May at the age of 95. She in 1960 to describe a group of artists with a postmodern was trained as an artist at the Art Students League in New bent. Though often compared to Pop Art, Noweau York, studying primarily with the sculptor Alexander Realisrne did not celebrate artists who turned soup cans into Archipenko. During the 1930s's, she worked as one of the art objects, but instead "reveled in rubbish, torn posters, directors of the WAart program in New York. Her portrait abandoned meals." He was founder of the Domus Academy head of Marcel Duchamp is in the collection of the in Milan, a post-graduate research institute for fashion and Wadsworth Athenaeum in rd. design and beginning in 1985, he edited the Mlan-based magazine D'Ars. He frequently organized large Fernmd Fonssagrives, a photographer known for his international exhibitions, such as the Olympic Sculpture elegant pictures of his first wife, the noted model Lisa Park in Seoul in the late 1980s and the 1999 Venice Fonssagrives, and his later pictures of emale nudes wiht Biennale, as well as shows in Shanghai and Havana (2000) patterns of light on their skin, died in April at the age of 93. and in Istanbul (200 1). -

Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art Premieres New Work by Artist Allison Schulnik

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Feb. 6, 2014 Media Only: Amanda Young, (860) 838-4082 [email protected] WADSWORTH ATHENEUM MUSEUM OF ART PREMIERES NEW WORK BY ARTIST ALLISON SCHULNIK On view Feb. 6 – May 4, 2014, the Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art’s MATRIX 168 will feature work by widely-acclaimed artist Allison Schulnik. Centering on the museum premiere of “Eager” (2014), a new stop-motion, clay animation video by Schulnik, the exhibition will also include the artist’s 2011 film, “Mound,” which Schulnik describes as, “a celebration of the moving painting,” and which The New York Times says, “demonstrates the thrill of old- fashioned animation.” Schulnik’s clay animation videos feature lonely, marginalized characters accompanied by moody and obscure musical pieces. Both “Eager” and “Mound” exemplify the thrilling effects of old-fashioned animation techniques, which Schulnik learned while studying with legendary animator Jules Engel, a contributor to Disney classics “Fantasia” (1940) and “Bambi” (1942), and founding director of the Experimental Animation Program at California Institute of the Arts (Cal Arts). “I draw from dance, movies, music, cartoons, once-loved discarded relics, long-loved junk classics, myself and loved ones, strangers and stars, fools and sages,” said Schulnik. “I like to meld earthly fact, blatant fiction and a love for raw material and the hand-made to form a stage of tragedy, farce, and ominous, crude beauty.” Accompanying Schulnik’s videos, the adjacent gallery will feature a fantastical installation of 14 paintings and a motley cast of sculptures on mismatched pedestals—which directly connect to her videos through subject matter, color palette and heavy impasto effects. -

Allison Schulnik's Hobo Clown

Allison Schulnik’s Hobo Clown: grotesque resistance, storytelling metamorphosis and Franz Kafka by william boyd fraser, sculptor A Major Research Paper presented to OCAD University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Contemporary Art, Design and New Media Art Histories Toronto, Ontario, Canada, April, 2015 © william boyd fraser, 2015 ii Author’s Declaration i hereby declare that i am the sole author of this thesis. this is a true copy of the thesis, including any required final versions, as accepted by my examiners. i authorize OCAD University to lend this thesis to other institutions or individuals for the purpose of scholarly research. i understand that my thesis may be made electronically available to the public. i further authorize OCAD University to reproduce this thesis by photocopying or by other means, in total or in part, at the request of other institutions or individuals for the purpose of scholarly research. iii Abstract Allison Schulnik’s Hobo Clown clay stop-motion film is analyzed using a rhetorical triangulation of persuasion. A hybrid method alternates Schulnik, reader and an imaginary Other for three points of view providing comparisons of story perspective. Franz Kafka’s The Metamorphosis provides an exemplary third person narrative style. A history of stop-motion animation, hobos and clowns, along with animation theory of metamorphosis contribute to a hypothetical null questioning of Schulnik’s grotesque as a constructive identity resisting expectation. Mise-en-scène of staging and music provide sensory, visual and auditory description along with primary source materials and theoretical insight for describing a reading of the film’s grotesque transformations. -

Stop Motion & Motion Capture Stop Motion

VolVol 22 IssueIssue 1111 February 1998 Stop Motion & Motion Capture The Politics of Performance Animation FoamFoam PuppetPuppet FrabicationFrabication ExplainedExplained BarryBarry Purves Purves ThrowsThrows DownDown thethe GauntletGauntlet Little Big Estonia InsideInside MedialabMedialab Table of Contents February, 1998 Vol. 2, No. 11 4 Editor’s Notebook Animation and its many changing faces... 5 Letters: [email protected] STOP-MOTION & MOTION-CAPTURE 6 Who’s Data Is That Anyway? Gregory Peter Panos, founding co-director of the Performance Animation Society, describes a new fron- tier of dilemmas, the politics of performance animation. 9 Boldly Throwing Down the Gauntlet In our premier issue, acclaimed stop-motion animator Barry J.C. Purves shared his sentiments on the coming of the computer. Now Barry’s back to share his thoughts on the last two years that have been both exhilarating and disappointing for him. 14 A Conversation With... In a small, quiet cafe, motion-capture pioneer Chris Walker and outrageous stop-motion animator Corky Quakenbush got together for lunch and discovered that even though their techniques may appear to be night and day, they actually have a lot in common. 21 At Last, Foam Puppet Fabrication Explained! How does one build an armature from scratch and end up with a professional foam puppet? Tom Brierton is here to take us through the steps and offer advice. 27 Little Big Estonia:The Nukufilm Studio On the 40th anniversary of Estonia’s Nukufilm, Heikki Jokinen went for a visit to profile the puppet ani- mation studio and their place in the post-Soviet world. 31 Wallace & Gromit Spur Worldwide Licensing Activity Karen Raugust takes a look at the marketing machine behind everyone’s favorite clay characters, Wallace & Gromit. -

Animation: a World History

ANIMATION: A WORLD HISTORY Volume I: Foundations— The Golden Age Giannalberto Bendazzi CRC Press Taylor &. Francis Croup A FOCAL PRESS BOOK Contents Contributors and Collaborators xi Pre-History II 14 A Static Mirror? 14 Acknowledgements xii The Flipbook 15 1 Foundations 1 Emile Reynaud 15 Birth of the Theatre 16 What It Is 1 Optique The Theatre and How Mapping Chaos 1 Optique It Worked 18 Turning Points 1 On with the Lantern Show 19 Periods 1 Colour Music 19 Guilty, but with an Explanation 2 Cinema of Attractions 21 Traces 2 Frame Frame 21 You Won't Find... 3 by Arthur 22 A Hybrid 3 Melbourne-Cooper Walter Robert Booth 23 Edwin Stanton Porter 24 The First Period 5 James Stuart Blackton 25 The First Period spans the years before the screening of Emile CohTs film Fantasmagorie in The Second Period 27 France. There is no 'animation' as such Paris, The Second Period embraces the entire silent there, but the film still incorporates many fea¬ film era and ends with a specific date: 18 Novem¬ tures that look like what nowadays we would ber 1928, the day of the public screening of Walt consider to be animation. We will call this Disney's first 'talkie', the short film Steamboat Wil¬ period 'Before Fantasmagorie (0-1908)'. lie. We will call this period 'The Silent Pioneers (1908-1928)'. 2 Before Fantasmagorie (0-1908) 7 3 The Silent Pioneers (1908-1928) 29 Archaeology 7 The Cradle 29 Phidias' Animating Chisel 8 Days of Heaven and Hell 29 Representation 8 Culture 29 The Motion Analysis 8 Cinema 30 Music 9 Narrative and Non-Narrative 30 The Meaning -

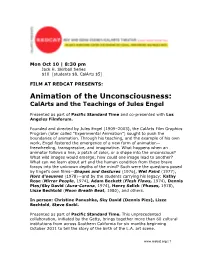

Animation of the Unconsciousness: Calarts and the Teachings of Jules Engel

Mon Oct 10 | 8:30 pm Jack H. Skirball Series $10 [students $8, CalArts $5] FILM AT REDCAT PRESENTS: Animation of the Unconsciousness: CalArts and the Teachings of Jules Engel Presented as part of Pacific Standard Time and co-presented with Los Angeles Filmforum. Founded and directed by Jules Engel (1909–2003), the CalArts Film Graphics Program (later called “Experimental Animation”) sought to push the boundaries of animation. Through his teaching, and the example of his own work, Engel fostered the emergence of a new form of animation— freewheeling, transgressive, and imaginative. What happens when an animator follows a line, a patch of color, or a shape into the unconscious? What wild images would emerge; how could one image lead to another? What can we learn about art and the human condition from these brave forays into the unknown depths of the mind? Such were the questions posed by Engel’s own films—Shapes and Gestures (1976), Wet Paint (1977), Hors d’oeuvres (1978)—and by the students carrying his legacy: Kathy Rose (Mirror People, 1974), Adam Beckett (Flesh Flows, 1974), Dennis Pies/Sky David (Aura-Corona, 1974), Henry Selick (Phases, 1978), Lisze Bechtold (Moon Breath Beat, 1980), and others. In person: Christine Panushka, Sky David (Dennis Pies), Lisze Bechtold, Steve Socki. Presented as part of Pacific Standard Time. This unprecedented collaboration, initiated by the Getty, brings together more than 60 cultural institutions from across Southern California for six months beginning October 2011 to tell the story of the birth of the L.A. art scene. www.redcat.org | 1 Pacific Standard Time is an initiative of the Getty. -

The Toy Like Nature: on the History and Theory of Animated Motion

THE TOY LIKE NATURE: ON THE HISTORY AND THEORY OF ANIMATED MOTION by Ryan Pierson B.A., University of Georgia, 2004 M.A., New York University, 2005 Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of The Kenneth P. Dietrich School of Arts and Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Pittsburgh 2012 UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH KENNETH P. DIETRICH SCHOOL OF ARTS AND SCIENCES This dissertation was presented by Ryan Pierson It was defended on August 21, 2012 and approved by Marcia Landy, Distinguished Professor, Department of English Mark Lynn Anderson, Associate Professor, Department of English Peter Machamer, Professor, Department of History and Philosophy of Science Scott Bukatman, Professor, Department of Art and Art History, Stanford University Dissertation Advisor: Daniel Morgan, Assistant Professor, Department of English ii Copyright © by Ryan Pierson 2012 iii THE TOY LIKE NATURE: ON THE HISTORY AND THEORY OF ANIMATED MOTION Ryan Pierson, Ph.D. University of Pittsburgh, 2012 This dissertation examines some key assumptions behind our prevailing idea of animation, arguing that our idea of animation is not, as is often implicitly assumed, an ahistorical category of manipulated imagery, but the result of a complex network of contingent processes. These assumptions, from the aesthetic end, largely emerged from the postwar rise of figurative (or noncartoon, nonabstract) animation—a “new era” which critic André Martin characterized as “marked by the widest possible range of techniques and processes.” From the other end, animation is tied to widespread assumptions from science that assert the biological, automatic nature of visual illusion. Animation’s unique status as a medium of visual movement that can arise from any kind of material (drawings, puppets, computer graphics, etc.), thus yields a paradox that I call “animated automatism”: the fact that, in order to assert its open-ended freedom as an art form, animation must acknowledge the reductive mechanics of perception.