Pacific Island Economic Report: Tuvalu 2006

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Action Plan for Implementing the Convention on Biological Diversity's Programme of Work on Protected Areas

Action Plan for Implementing the Convention on Biological Diversity’s Programme of Work on Protected Areas (INSERT PHOTO OF COUNTRY) (TUVALU) Submitted to the Secretariat of the Convention on Biological Diversity October 6, 2011 Protected area information: PoWPA Focal Point: Mrs. Tilia Asau Assistant Environment officer-Biodiversity Department of Environment Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Trade, Tourism, Environment & Labour. Government of Tuvalu. Email:[email protected] Lead implementing agency: Department of Environment. Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Trade, Tourism, Environment & Labour. Multi-stakeholder committee: Advisory Committee for Tuvalu NBSAP project Description of protected area system National Targets and Vision for Protected Areas Vission: “Keeping in line with the Aichi targets - By the year 2020, Tuvalu would have a clean and healthy environment, full of biological resources where the present and future generations of Tuvalu will continue to enjoy the equitable sharing benefits of Tuvalu’s abundant biological diversity” Mission: “We shall apply our traditional knowledge, together with innovations and best practices to protect our environment, conserve and sustainably use our biological resources for the sustainable benefit of present and future Tuvaluans” Targets: Below are the broad targets for Tuvalu as complemented in the Tuvalu National Biodiversity Action Plan and NSSD. To prevent air, land , and marine pollution To control and minimise invasive species To rehabilitate and restore degraded ecosystems To promote and strengthen the conservation and sustainable use of Tuvalu’s biological diversity To recognize, protect and apply traditional knowledge innovations and best practices in relation to the management, protection and utilization of biological resources To protect wildlife To protect seabed and control overharvesting in high seas and territorial waters Coverage According to World data base on Protected Areas, as on 2010, 0.4% of Tuvalu’s terrestrial surface and 0.2% territorial Waters are protected. -

2017 Tuvalu Mini CPH Form 3

Generated by winston, Apr 09, 2019 16:09 Sections: 4, Sub-sections: 17, Questionnaire created by togar, Mar 04, 2019 14:56 Questions: 209. Last modified by togar, Mar 04, 2019 14:56 Questions with enabling conditions: 123 Questions with validation conditions:66 Shared with: Rosters: 10 luisr (never edited) Variables: 3 winston (never edited) 2017 Tuvalu Mini CPH Form 3 SURVEY IDENTIFICATION INFORMATION QUESTIONNAIRE DESCRIPTION IDENTIFICATION No sub-sections, No rosters, Questions: 21, Static texts: 1. HOUSEHOLD No sub-sections, Rosters: 6, Questions: 71, Static texts: 1. PERSON Sub-sections: 17, Rosters: 4, Questions: 110, Static texts: 4, Variables: 3. ENDING No sub-sections, No rosters, Questions: 7. APPENDIX A — ENABLING CONDITIONS APPENDIX B — VALIDATION CONDITIONS AND MESSAGES APPENDIX C — INSTRUCTIONS APPENDIX D — CATEGORIES APPENDIX E — CATEGORIES FILTERS LEGEND 1 / 49 SURVEY IDENTIFICATION INFORMATION QUESTIONNAIRE DESCRIPTION Basic information Title 2017 Tuvalu Mini CPH Form 3 SURVEY IDENTIFICATION INFORMATION QUESTIONNAIRE DESCRIPTION 2 / 49 IDENTIFICATION C1. CENSUS ID TEXT censusID SCOPE: IDENTIFYING E1 $censIdOk M1 The Census ID entered is invalid. Please double check the entered valu es match the Census ID in CPH Form 1. C2. ISLAND SINGLE-SELECT: COMBO BOX Island_code SCOPE: IDENTIFYING E1 ((censusID.ToLower().Left(1) == "x" && self == 0)?true:f 00 Test Island alse) || ((censusID.ToLower().Left(1) == "a" && self == 1)?true:false) || ((censusID.ToLower().Left(1) == "b" && 01 Nanumea self == 2)?true:false) || (( And 457 other symbols [1] 02 Nanumaga M1 The Island entered is not associated with the Census ID. 03 Niutao 04 Nui 05 Vaitupu 06 Nukufetau 07 Funafuti 08 Nukulaelae 09 Niulakita STATIC TEXT Census ID: %censusID% C3. -

South Pacific

South Pacific Governance in the Pacific: the dismissal of Tuvalu's Governor-General Tauaasa Taafaki BK 338.9 GRACE FILE BARCOOE ECO Research School of Pacific and Asian \\\\~ l\1\1 \ \Ul\\ \ \\IM\\\ \\ CBR000029409 9 Enquiries The Editor, Working Papers Economics Division Research School of Pacific and Asian Studies The Australian National University Canberra 0200 Australia Tel (61-6) 249 4700 Fax (61-6) 257 2886 ' . ' The Economics Division encompasses the Department of Economics, the National Centre for Development Studies and the Au.§.tralia-J.apan Research Centre from the Research School of Pacific and Asian Studies, the Australian National University. Its Working Paper series is intended for prompt distribution of research results. This distribution is preliminary work; work is later published in refereed professional journals or books. The Working Papers include V'{Ork produced by economists outside the Economics Division but completed in cooperation with researchers from the Division or using the facilities of the Division. Papers are subject to an anonymous review process. All papers are the responsibility of the authors, not the Economics Division. conomics Division Working Papers " South Pacific Governance in the Pacific: the dismissal of Tuvalu's Governor-General Tauaasa Taafaki / o:,;7 CJ<,~ \}f ftl1 L\S\\ltlR~ Research School of Pacific and Asian Studies C;j~••• © Economics Division, Research School of Pacific and Asian Studies, The Australian National University, 1996. This work is copyright. Apart from those uses which may be permitted under the Copyright Act 1968 as amended, no part may be reproduced by any process without written permission from the publisher. -

![Sector Assessment (Summary): Transport (Water Transport [Nonurban])](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/5336/sector-assessment-summary-transport-water-transport-nonurban-205336.webp)

Sector Assessment (Summary): Transport (Water Transport [Nonurban])

Outer Island Maritime Infrastructure Project (RRP TUV 48484) SECTOR ASSESSMENT (SUMMARY): TRANSPORT (WATER TRANSPORT [NONURBAN]) Sector Road Map 1. Sector Performance, Problems, and Opportunities 1. Tuvalu is an independent constitutional monarchy in the southwest Pacific Ocean. Formerly known as the Ellice Islands, they separated from the Gilbert Islands after a referendum in 1975, and achieved independence from the United Kingdom on 1 October 1978. The population of 10,100 live on Tuvalu’s nine atolls, which have a total land area of 27 square kilometers. 1 The nine islands, from north to south, are Nanumea, Niutao, Nanumaga, Nui, Vaitupu, Nukufetau, Funafuti, Nukulaelae, and Niulakita. 2. About 43% of the population lives on the outer islands. The small land mass, combined with infertile soil, create a heavy reliance on the sea. The primary economic activities are fishing and subsistence farming, with copra being the main export. 3. The effectiveness and efficiency of maritime transport is highly correlated and integral to the economic development of Tuvalu. Government-owned ships are the only means of transport among the islands. The government fleet includes three passenger and cargo ships operated by the Ministry of Communication and Transport (MCT), a research boat under the Fishery Department, and a patrol boat. 2 The passenger and cargo ships travel from Funafuti to the outer islands and Fiji, so each island only has access to these ships once every 2–3 weeks. Table 1 shows the passengers and cargo carried by the ships in recent years. In addition to the regular services, these ships are used for medical evacuations. -

Declaration of Internal Waters

DECLARATION OF INTERNAL WATERS L.N.4/89 DECLARATION OF INTERNAL WATERS CAP. 24A Arrangement of Sections DECLARATION OF INTERNAL WATERS Arrangement of Sections Section SCHEDULE 6 Supporting Documents ENDNOTES 9 Table of Legislation History ...........................................................................................9 Table of Renumbered Provisions ....................................................................................9 Table of Endnote References ..........................................................................................9 L.N.4/89 Page 3 Section Error! No text of DECLARATION OF INTERNAL WATERS specified style in document. DECLARATION OF INTERNAL WATERS L.N.4/89 MARINE ZONES (DECLARATION) ACT 1983 ENACTED BY THE PARLIAMENT OF TUVALU Commencement [Date] IN EXERCISE of the powers conferred on him by section 5(2) of the Marine Zones (Declaration) Act 1983 as amended by the Marine Zones (Declaration) Amendment Act 1988, the Minister in accordance with the rules of international law HEREBY DECLARES that the geographical coordinates, specifying the geodetic datums, listed by island in the schedule attached are the points between which closing lines are to be drawn for the purpose of determining the outer limits of the internal waters of Tuvalu in the case of the mouths of or entrances to lagoons. L.N.4/89 Page 5 Schedule CAP. 24A DECLARATION OF INTERNAL WATERS Schedule Nanumea and Lakena Atoll Latitude (S) Longitude (E) A line joining points #1 and #2. A second line joining points #3 and #4. Point #1 05 39' 01” 176 04' 40” #2 05 39' 29” 176 06' 43” #3 05 39' 10” 176 04' 39” #4 05 40' 18” 176 06' 28” Niutao Atoll NIL Nanumaga Atoll NIL Nui Atoll Lines joining points #5 through #8. A second line joining points #9 and #10. -

Metronome Trip 1 to Nanumea, Nanumaga and Niutao, 18 June - 4 July 2016

Tuvalu Fisheries Department: Coastal Section: Trip Report Metronome Trip 1 to Nanumea, Nanumaga and Niutao, 18 June - 4 July 2016 Lale Petaia, Semese Alefaio, Tupulaga Poulasi, Viliamu Petaia, Filipo Makolo, Paeniu Lopati, Manuao Taufilo, Maani Petaia, Simeona Italeli, Leopold Paeniu, Tetiana Panapa, Aso Veu 9th August 2016 The mission After nearly a month of preparation, the mission to fulfil the first metronome trip under the NAPA II project was made to the three northern islands (Niutao, Nanumea & Nanumaga). The team mission includes several fisheries officers from both the coastal and the Operational and Development division, two NAPA II officers and three other staffs from other government departments. The full list of the team is provided on the appendix. Although, there were many target activities conducted during this mission, however, the focus of this report is to highlight specific activities that were undertaken specifically by the coastal division staffs during this trip. The overall objective of the mission is to implement fisheries related activities under component 1 of the NAPA II project. These are; I. House hold surveys on socio-economic data II. Collection of Ciguatera data III. Run creel survey trials IV. Canoe and boat survey V. LMMA work VI. Collection of fishery information and data The mission departed Funafuti on 18th June, and return on 4th July. The first island to visit was Niutao, where we stayed for 9 days. The visit to Niutao was the longest out of the three islands due to the unexpected problem we encounter during our stay on the island which will be mention later on this report. -

The Project for Pilot Gravel Beach Nourishment Against Coastal Disaster on Fongafale Island in Tuvalu

MINISTRY OF FOREIGN AFFAIRS, TRADES, TOURISM, ENVIRONMENT AND LABOUR THE GOVERNMENT OF TUVALU THE PROJECT FOR PILOT GRAVEL BEACH NOURISHMENT AGAINST COASTAL DISASTER ON FONGAFALE ISLAND IN TUVALU FINAL REPORT (SUPPORTING REPORT) April 2018 JAPAN INTERNATIONAL COOPERATION AGENCY NIPPON KOEI CO., LTD. FUTABA INC. GE JR 18-058 MINISTRY OF FOREIGN AFFAIRS, TRADES, TOURISM, ENVIRONMENT AND LABOUR THE GOVERNMENT OF TUVALU THE PROJECT FOR PILOT GRAVEL BEACH NOURISHMENT AGAINST COASTAL DISASTER ON FONGAFALE ISLAND IN TUVALU FINAL REPORT (SUPPORTING REPORT) April 2018 JAPAN INTERNATIONAL COOPERATION AGENCY NIPPON KOEI CO., LTD. FUTABA INC. Table of Contents Supporting Report-1 Study on the Quality and Quantity of Materials in Phase-1 (quote from Interim Report 1) .............................................................. SR-1 Supporting Report-2 Planning and Design in Phase-1 (quote from Interim Report 1) ............ SR-2 Supporting Report-3 Design Drawing ..................................................................................... SR-3 Supporting Report-4 Project Implementation Plan in Phase-1 (quote from Interim Report 1)................................................................................................. SR-4 Supporting Report-5 Preliminary Environmental Assessment Report (PEAR) ....................... SR-5 Supporting Report-6 Public Consultation in Phase-1 (quote from Interim Report 1) .............. SR-6 Supporting Report-7 Bidding Process (quote from Progress Report) ...................................... SR-7 Supporting -

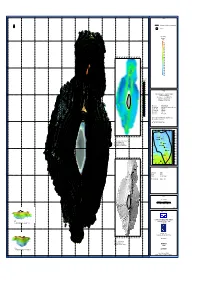

Nanumanga Tuvalu Bathymetry

414000 E 416000 E 418000 E 420000 E 422000 E 424000 E 426000 E 428000 E 430000 E 432000 E 434000 E LEGEND 150 Bathymetric contours shown at 20 metre intervals Land area Colour Banding Bathymetry Metres 100 200 300 400 500 600 700 800 900 420000 421000 422000 423000 424000 425000 426000 427000 428000 429000 1000 1100 1200 1300 1400 1500 1600 1700 1800 1900 2000 2100 Slope angle (degrees) 80 75 70 65 60 NOTES 55 Observed soundings have been reduced to Chart Datum 50 defined as 0.7859 m below LAT, 45 1.985 m below mean sea level (MSL 1993-1994), 40 and 4.0123 m below the fixed height of Benchmark 22 on Funafuti, Tuvalu 35 30 25 Date of Survey 08/09 to 24/10/2004 20 Acquisition system Reson SeaBat 8160 multibeam echosounder Collection software Hypack 4.3 15 Processing software Hypack 4.3A 10 Data presentation Surfer 8.03 5 Survey vessel M.V. Turagalevu 0 Backdrop image is a 2003 IKONOS satellite image rectified using differential GPS ground control points. NOT TO BE USED FOR NAVIGATION LOCATION 0 m 4° S 500 m 1000 m 9298000 9299000 9300000 9301000 9302000 9303000 9304000 9305000 9306000 9307000 9308000420000 9309000 9310000 9311000 9312000 9313000 421000 422000 423000 424000 425000 426000 427000 428000 429000 9298000 9299000 9300000 9301000 9302000 9303000 9304000 9305000 9306000 9307000 9308000 9309000 9310000 9311000 9312000 9313000 Nanumea 6° S 1500 m INSET Nanumanga Niutao Gradient slope angle map generated from 20 m 2000 m gridded multibeam bathymetry. Nui Red indicates higher slope angles. -

Coastal Erosion and Management of Amatuku Island, Funafuti Atoll, Tuvalu

COASTAL EROSION AND MANAGEMENT OF AMATUKU ISLAND, FUNAFUTI ATOLL, TUVALU Chunting Xue SOPAC Secretariat August 1996 SOPAC Technical Report 234 This project was funded by the Government of the People's Republic of China [3] TABLE OF CONTENTS Page SUMMARY.................................................................................................................................. 6 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS............................................................................................................. 7 INTRODUCTION........................................................................................................................ 7 STUDY METHODS .................................................................................................................. 11 DEVELOPMENT HISTORY ..................................................................................................... 11 REEF FLAT AND BEACH........................................................................................................ 12 COASTAL EROSION............................................................................................................... 19 BORROW PIT AND CHANNEL ............................................................................................... 27 COASTAL MANAGEMENT ....................................................................................................... 31 CONCLUSIONS ....................................................................................................................... 31 RECOMMENDATIONS -

The Biology and Geology of Tuvalu: an Annotated Bibliography

ISSN 1031-8062 ISBN 0 7305 5592 5 The Biology and Geology of Tuvalu: an Annotated Bibliography K. A. Rodgers and Carol' Cant.-11 Technical Reports of the Australian Museu~ Number-t TECHNICAL REPORTS OF THE AUSTRALIAN MUSEUM Director: Technical Reports of the Australian Museum is D.J.G . Griffin a series of occasional papers which publishes Editor: bibliographies, catalogues, surveys, and data bases in J.K. Lowry the fields of anthropology, geology and zoology. The journal is an adjunct to Records of the Australian Assistant Editor: J.E. Hanley Museum and the Supplement series which publish original research in natural history. It is designed for Associate Editors: the quick dissemination of information at a moderate Anthropology: cost. The information is relevant to Australia, the R.J. Lampert South-west Pacific and the Indian Ocean area. Invertebrates: Submitted manuscripts are reviewed by external W.B. Rudman referees. A reasonable number of copies are distributed to scholarly institutions in Australia and Geology: around the world. F.L. Sutherland Submitted manuscripts should be addressed to the Vertebrates: Editor, Australian Museum, P.O. Box A285, Sydney A.E . Greer South, N.S.W. 2000, Australia. Manuscripts should preferably be on 51;4 inch diskettes in DOS format and ©Copyright Australian Museum, 1988 should include an original and two copies. No part of this publication may be reproduced without permission of the Editor. Technical Reports are not available through subscription. New issues will be announced in the Produced by the Australian Museum Records. Orders should be addressed to the Assistant 15 September 1988 Editor (Community Relations), Australian Museum, $16.00 bought at the Australian Museum P.O. -

Pacific Islands

THE PACIFIC ISLANDS POLITICS, ECONOMICS, AND INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS TE'O I.J. FAIRBAIRN CHARLES E. MORRISON RICHARD W. BAKER SHEREE A. GROVES THE PACIFIC ISLANDS THE EAST-WEST CENTER was established in Hawaii in 1960 by the United States Congress "to promote better relations and understand ing between the United States and the nations of Asia and the Pacific through cooperative study, training, and research:' Some 2,000 research fellows, graduate students, and professionals in business and government each year work with the Center's interna tional staff on major Asia-Pacific issues relating to population, economic and trade policies, resources and the environment, culture and com munication, and international relations. Since 1960, more than 27,000 men and women from the region have participated in the Center's cooperative programs. Officially known as the Center for Cultural and Technical Inter change Between East and West, Inc., the Center is a public, non-profit institution with an international board of governors. Principal funding comes from the United States Congress. Support also comes from more than twenty Asian and Pacific governments, as well as private agen cies and corporations. THE INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS PROGRAM (JRP) became an autonomous program within the East-West Center in 1989. The Program advances the Center's overall objectives through work on foreign poli cy and related political, economic, and security issues. Program pri orities are to 1) promote research and dialogue directed toward creating a stable, peaceful Asia/Pacific community; 2) identify issues in U.S. re lations with the Asia/Pacific region and recommend means of strength ening these relations; 3) improve understanding of individual societies of the region through cooperative research; and 4) promote contact and dialogue among the region's future leaders. -

The Case-Study of Fongafale, Atool of Funafuti

Shoreline of human-impacted coralline atolls: need for a concerted management. The case-study of Fongafale, atoll of Funafuti, Tuvalu Caroline Rufin The atoll of Funafuti (Tuvalu archipelago) is located in the South Pacific Ocean at latitude 8.31° South and longitude 179.13° East (Figure 1). According to its morphology, Fongafale island (atoll of Funafuti) can be split into three distinct geographical areas, i.e. the northern, central and southern parts. The present study deals with the central part, which results from the deposition of sediments from the two other areas following North and South longshore drifts. Marshall •• Islands, 1o·N Kiribati! . ~ ~· ... ' ... .. ·. ~ Samoa .. o_. •• Vanuatu b •! ; . b\ Fiji ,::::1 . ~ 0 Tonga .. ' '· : .... 2o·s New .. ~.'•. ' •• Caledon~. • • • 100· 110· 180' 170' 160"W Source : from Mclean et Hosking. 1991 Figure 1 Localisation of Tuvalu within the Pacific Bassin. 436 Coral reefs in the Pacifie: Status and monitoring, Resources and management Through the example of Fongafale island, the present study is aimed at thinking about the manage ment of low coralline islands confronted with erosion problems most often in relation with excessive coastal planning. This thought will be developed in terms of global geography while taking into account ail the environmental conditions. Our purpose will be not to demonstrate which of the two factors, Man or Nature, is the more disturb ing. However, from the analysis of our data set it is clear that the contribution of the former is greater than that of the latter. We will first draw a schedule of Fongafale lagoon shoreline from aerial pictures and topographical readings; it will be essential to understand the environmental problems which this atoll is submitted to.