Perceptions of Medieval Settlement, 'Handbook of Later Medieval Archaeology', Oxford University Press (In Press)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chain Cottage, 329 Thorpe Road, Longthorpe, Peterborough PE3 6LU

Chain Cottage, 329 Thorpe Road, Longthorpe, Peterborough PE3 6LU Chain Cottage, 329 Thorpe Road, OUTSIDE The reception hall is entered via a traditional front A particular feature of the property is the large plot Longthorpe Peterborough PE3 6LU door, tiled flooring and stairs rising to the first floor. which extends to approximately 0.2 acres and is The sitting room has a feature fireplace, beam and approached via a side lane from Thorpe Road which A charming Grade II listed thatched cottage windows to the front and rear elevations. The leads to Longthorpe Tower. There is a gated requiring full modernisation in the heart of the dining room has a feature fireplace, beam and entrance and ample off road parking and turning popular and sought-after area of Longthorpe windows to the front and side elevation. An inner leading to a detached garage. The gardens which enjoying a large plot and offering considerable hall with tiled flooring and understairs storage are part walled require some overhaul and there is scope. cupboard leads to the kitchen/breakfast room a patio area, two outside store and gated access to which is fitted with a basic range of kitchen units the front elevation. ▪ Grade II listed thatched cottage incorporating a stainless steel single bowl, double ▪ Requires full modernisation drainer sink unit, base and eyelevel storage PRINCIPAL MEASUREMENTS ▪ 2 receptions, kitchen, cloaks/w.c. cupboards, windows to side and rear elevation and Sitting room 15’7” x 12’10” ▪ 3 bedrooms and family bathroom large walk-in pantry ( 10’9” x 7’1” ) with window to Dining room 13’1” x 12’4” ▪ Large plot, garaging, outbuilding the side elevation. -

A HISTORY of OUR CHURCH Welcome To

A HISTORY OF OUR CHURCH Welcome to our beautiful little church, named after St Botolph*, the 7th century patron saint of wayfarers who founded many churches in the East of England. The present church on this site was built in 1263 in the Early English style. This was at the request and expense of Sir William de Thorpe, whose family later built Longthorpe Tower. At first a chapel in the parish of St John it was consecrated as a church in 1850. The church has been well used and much loved for over 750 years. It is noted for its stone, brass and stained glass memorials to men killed in World War One, to members of the St John and Strong families of Thorpe Hall and to faithful members of the congregation. Below you will find: A.) A walk round tour with a plan and descriptions of items in the nave and chancel (* means there is more about this person or place in the second half of this history.) The nave and chancel have been divided into twelve sections corresponding to the numbers on the map. 1) The Children’s Corner 2) The organ area 3) The northwest window area 4) The North Aisle 5) The Horrell Window 6) The Chancel, north side 7) The Sanctuary Area 8) The Altar Rail 9) The Chancel, south side 10) The Gaskell brass plaques 11) Memorials to the Thorpe Hall families 12) The memorial book and board; the font B) The history of St Botolph, this church and families connected to it 1) St Botolph 2) The de Thorpe Family, the church and Longthorpe Tower 3) History of the church 4) The Thorpe Hall connection: the St Johns and Strongs 5) Father O-Reilly; the Oxford Movement A WALK ROUND THE CHURCH This guide takes you round the church in a clockwise direction. -

Strategic Stone Study a Building Stone Atlas of Cambridgeshire (Including Peterborough)

Strategic Stone Study A Building Stone Atlas of Cambridgeshire (including Peterborough) Published January 2019 Contents The impressive south face of King’s College Chapel, Cambridge (built 1446 to 1515) mainly from Magnesian Limestone from Tadcaster (Yorkshire) and Kings Cliffe Stone (from Northamptonshire) with smaller amounts of Clipsham Stone and Weldon Stone Introduction ...................................................................................................................................................... 1 Cambridgeshire Bedrock Geology Map ........................................................................................................... 2 Cambridgeshire Superficial Geology Map....................................................................................................... 3 Stratigraphic Table ........................................................................................................................................... 4 The use of stone in Cambridgeshire’s buildings ........................................................................................ 5-19 Background and historical context ........................................................................................................................................................................... 5 The Fens ......................................................................................................................................................................................................................... 7 South -

Conduit 2012 N.P65

Conduit 49:Layout 1 7/9/11 20:08 Page 1 The Conduit 50th Edition Now Interactive Number 50 September 2012 - August 2013 Societies | lectures | conferences | groups | courses museums | archaeology | architecture local and family history The Conduit 2013 In compiling The Conduit this year we have tried to be totally inclusive, but appreciate that some organisations may have been omitted and note that some societies have not been able to finalise their 2012-2013 programmes at the time of publication. In this case, readers are advised to consult the website of the relevant organisation. Email and website addresses, where known, are included in The Conduit, and users of the online version can click on the relevant hyperlinks. We aim to send The Conduit to every listed local society in Cambridgeshire, as well as to museums and other relevant organisations. If you belong to an organisation whose details are not included, or which would like to receive copies of The Conduit next year, please contact the Editor, who will add your organisation’s details to the next issue. Wherever possible the information has been checked by a responsible individual in the relevant organisation, and so should be up to date at the time of printing. Further details of the activities of listed organisations are often available on their websites. Web addresses are included where known. I would finally like to thank the editor of The Conduit, Simon Barlow of the Haddon Library, for all his hard work in compiling and producing The Conduit this year. It is a considerable undertaking, but one that is very greatly valued, both by members of Cambridge Antiquarian Society and by others who use it to inform themselves of events and activities of interest across our richly historical county. -

River Nene Waterspace Study

River Nene Waterspace Study Northampton to Peterborough RICHARD GLEN RGA ASSOCIATES November 2016 ‘All rights reserved. Copyright Richard Glen Associates 2016’ Richard Glen Associates have prepared this report in accordance with the instructions of their clients, Environment Agency & the Nenescape Landscape Partnership, for their sole DQGVSHFL¿FXVH$Q\RWKHUSHUVRQVZKRXVHDQ\LQIRUPDWLRQFRQWDLQHGKHUHLQGRVRDW their own risk. River Nene Waterspace Study River Nene Waterspace Study Northampton to Peterborough On behalf of November 2016 Prepared by RICHARD GLEN RGA ASSOCIATES River Nene Waterspace Study Contents 1.0 Introduction 3.0 Strategic Context 1.1 Partners to the Study 1 3.1 Local Planning 7 3.7 Vision for Biodiversity in the Nene Valley, The Wildlife Trusts 2006 11 1.2 Aims of the Waterspace Study 1 3.1.1 North Northamptonshire Joint Core Strategy 2011-2031 7 3.8 River Nene Integrated Catchment 1.3 Key Objectives of the Study 1 3.1.2 West Northamptonshire Management Plan. June 2014 12 1.4 Study Area 1 Joint Core Strategy 8 3.9 The Nene Valley Strategic Plan. 1.5 Methodology 2 3.1.3 Peterborough City Council Local Plan River Nene Regional Park, 2010 13 1.6 Background Research & Site Survey 2 Preliminary Draft January 2016 9 3.10 Destination Nene Valley Strategy, 2013 14 1.7 Consultation with River Users, 3.2 Peterborough Long Term Transport 3.11 A Better Place for All: River Nene Waterway Providers & Local Communities 2 Strategy 2011 - 2026 & Plan, Environment Agency 2006 14 Local Transport Plan 2016 - 2021 9 1.8 Report 2 3.12 Peterborough -

Conservation Bulletin 3

Conservation Bulletin, Issue 3, October 1987 Area Conservation Strategy 1–2 Editorial 2 Conservation Studio 3 Grants, April – July 1987 4 What price Fleet Street? 5 What is a building? 6–7 Diary dates 7 Ancient monuments in the countryside 8–9 Tilestones 9–10 Civic Trust Regeneration Unit 10 Listing decisions 10 Archaeological resource management 11 Excavations at Birdoswald 1987 12 (NB: page numbers are those of the original publication) AREA CONSERVATION STRATEGY We asked Peter Robshaw of the Civic Trust to comment on our Area Conservation Strategy discussion paper. He writes: The Discussion Paper ‘Area Conservation Strategy’ contains much to commend it. In particular, it envisages some redistribution of grant-aid to needier areas and indicates a greater readiness on the part of English Heritage to be more interventionist in local planning and conservation issues. The former may not be too welcome to those local authorities in whose areas Town Schemes and Section 10 grants have been available for some considerable time, while the latter may not please those local authorities where the level of conservation activity is fairly low. But for those who care about safeguarding the historic fabric of our cities, towns, and villages, these proposals are very welcome. It seems reasonable to expect that in those cases where grants have been available and taken up over a long period, a rolling programme of conservation schemes should become self-sustaining without the continued help of English Heritage as local confidence is built up. This would serve to free scarce resources for the hard-pressed areas, such as industrial towns in the north of England where there is often a rich architectural inheritance with inadequate funding to maintain it. -

(Public Pack)Agenda Document for Planning and Environmental

Public Document Pack AB PLANNING AND ENVIRONMENTAL PROTECTION COMMITTEE TUESDAY 23 MARCH 2021 1.30 PM VENUE: Peterborough City Council Youtube page AGENDA Page No 1. Apologies for Absence 2. Declarations of Interest At this point Members must declare whether they have a disclosable pecuniary interest, or other interest, in any of the items on the agenda, unless it is already entered in the register of members’ interests or is a “pending notification “ that has been disclosed to the Solicitor to the Council. 3. Members' Declaration of intention to make representations as Ward Councillor 4. Minutes of the Meeting Held on: 3 - 22 To approve the minutes of the meeting held on: 26 January 2021; and 23 February 2021 5. Development Control and Enforcement Matters 5.1 19/00347/FUL - Ferry Meadows Country Park Ham Lane Orton 23 - 160 Waterville Peterborough. Recording of Council Meetings: Any member of the public may film, audio-record, take photographs and use social media to report the proceedings of any meeting that is open to the public. Audio-recordings of meetings may be published on the Council’s website. A protocol on this facility is available at: http://democracy.peterborough.gov.uk/ecSDDisplay.aspx?NAME=Protocol%20on%20the%20use%20of%20Recor ding&ID=690&RPID=2625610&sch=doc&cat=13385&path=13385 Committee Members: Councillors: G Casey (Vice Chairman), C Harper (Chairman), P Hiller, R Brown, Warren, Hussain, Iqbal, Jones, B Rush, Hogg and Bond Substitutes: Councillors: N Sandford, Simons, M Jamil and E Murphy Further information about this meeting can be obtained from Karen Dunleavy on telephone 01733 296334452233 or by email – [email protected] 1 CASE OFFICERS: Planning and Development Team: Nicholas Harding, Sylvia Bland, Janet Maclennan, David Jolley, Louise Simmonds,, Amanda McSherry, Matt Thomson, Asif Ali, Michael Freeman, Jack Gandy, Carry Murphy, Mike Roberts, Karen Ip, Shaheeda Montgomery and Susan Shenston Minerals and Waste: Alan Jones Compliance: Jason Grove, Amy Kelley and Alex Wood-Davis NOTES: 1. -

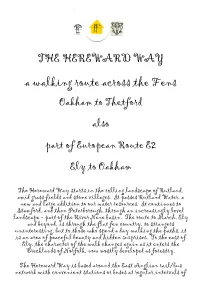

THE HEREWARD WAY a Walking Route Across the Fens Oakham to Thetford Also Part of European Route E2 Ely to Oakham

THE HEREWARD WAY a walking route across the Fens Oakham to Thetford also part of European Route E2 Ely to Oakham The Hereward Way starts in the rolling landscape of Rutland, amid grass fields and stone villages. It passes Rutland Water, a new and large addition to our water resources. It continues to Stamford, and then Peterborough, through an increasingly level landscape - part of the River Nene basin. The route to March, Ely and beyond, is through the flat fen country, to strangers uninteresting, but to those who spend a day walking the paths, it is an area of peaceful beauty and hidden surprises. To the east of Ely, the character of the walk changes again as it enters the Brecklands of Norfolk, now mostly developed as forestry. The Hereward Way is based around the East Anglian rail/bus network with convenient stations or buses at regular intervals of about 16kms. This route is dedicated to two indomitable fenmen John and John ------------ooooooo0ooooooo------------ Acknowledgements The development of the Hereward Way would not have been possible without a great deal of help from a large number of people, and my grateful thanks are extended as follows. To those walkers in the surrounding region who have expressed an interest in, and walked, parts of the original route. To Dr & Mrs Moreton, Henry Bridge and John Andrews, for particular encouragement at the conception. To the local Groups of the Ramblers' Association in Thetford, Cambridge, Peterborough, Stamford and Northampton; and the Footpath Officers and other officers of the County and District Councils, who provided additional information and support. -

Thomas Deacon Booklet

The Legacy of Thomas Deacon Produced by Thomas Deacon Foundation Thomas Deacon was a wealthy wool merchant and 1651 philanthropist. Born in 1651, he married Mary Thomas Deacon born Harvey of Spalding in 1673. 1673 Thomas was a prominent figure in the local area, Married Mary Harvey of owning a number of properties within Spalding Peterborough and the surrounding area, including farms, cottages and Longthorpe Tower. 1679 Became a Peterborough Thomas Deacon died on 19 August 1721, and was Feoffee laid to rest on 24 August 1721 in Peterborough Cathedral. 1683 Appointed Governor of Town Estates 1701 Acquired New Manor The Deacon (Longthorpe Tower) Memorial in Peterborough 1704 Cathedral. Appointed High Sheriff of Each year a Wreath Northampton Laying Ceremony takes place in 1721 honour of the Died on 19 August founder, Thomas Deacon. QuidQuid Agas Prudenter Agas Thomas Deacon bequeathed in his Will, dated 13 January 1719, that: ‘...My messuage and two freehold cottages and appurtenances the orchard, garden, yards and barns… assign my freehold farm… all profits from time to time and at all times for ever, however arising and proceeding…to be duly applied for the endowing and setting up of a school and schoolhouse in Peterborough… for teaching and instructing twenty poor boys…to read, write and cast accounts…’ The Will gave the responsibility and management of the school to the Vicar of St John Baptist, Peterborough and the Feoffees. The Will devised the following for the benefit of the school: i) Willow Hall Farm, including 231 acres 21 poles plus farm buildings ii) Newborough, 2 acres 0 roods 26 poles iii) Padmholme (Flag Fen) 4 acres 1 rood iv) Barsonly Close, Whittlesey, 28 acres v) Unspecified land at Stanground whose rent goes to Willow Hall Farm Feoffees, silmilar to todays local councillors, were a form of local government who in 1571 were entrusted (emfeoffeed) by other citiizens to control and administer land and charities in and around Extract of Thomas Deacon’s Will from Peterborough. -

Conference Programme

ANNUAL CONFERENCE 10th JULY TO 14th JULY 2015 THE ARCHITECTURE, ART AND ARCHAEOLOGY OF PETERBOROUGH CATHEDRAL AND THE SOKE OF PETERBOROUGH DRAFT PROGRAMME (11.06.2015) Friday 10th July 12.30 – 1.50pm Registration open at The Bull Hotel for collection of badges and conference packs. 1.00 – 1.50pm Sandwich lunch provided at The Bull Hotel. Please note that it is an approximately 5-7 minute walk from the hotel to the John Clare Theatre. 2.00 – 2.15pm John Clare Theatre: Welcome from the BAA President and Introductions Session 1 Chaired by Richard Halsey 2.15 – 2.45pm Charles O’Brien Revising Pevsner 2.45 – 3.15pm Stephen Upex The Roman Occupation of the Lower Nene Valley 3.15 – 3.45pm Tea at the John Clare Theatre 1 of 7 Session 2 Chaired by David Stocker 3.45 – 4.15pm Rosemary Cramp The Pre-Conquest Sculpture of Peterborough and Its Surrounding Area 4.15 – 4.45pm Richard Gem Peterborough – Medeshamstede: A Review of the Evidence for the Anglo-Saxon Abbey Church 4.45 – 5.15pm T. A. Heslop The Missal of Robert of Jumièges and Manuscript Production in Peterborough c.1015–35 5.15 – 5.30pm Coach pickup at the John Clare Theatre 5.30 – 7.15pm Visit to Flag Fen where the President’s reception is held. 7.15 – 8.00pm Checking in at The Bull Hotel 8.00pm Dinner at The Bull Hotel A two-course buffet dinner. Please ensure that you have signed up for one of the four groups for the site visits and put the appropriate coloured sticky label on your badge. -

A HISTORY of OUR CHURCH Welcome to Our Beautiful Little

A HISTORY OF OUR CHURCH Welcome to our beautiful little church, named after St Botolph*, the 7th century patron saint of wayfarers who founded many churches in the East of England. The present church on this site was built in 1263 in the Early English style. This was at the request and expense of Sir William de Thorpe, whose family later built Longthorpe Tower. At first a chapel in the parish of St John it was consecrated as a church in 1850. The church has been well used and much loved for over 750 years. It is noted for its stone, brass and stained glass memorials to men killed in World War One, to members of the St John and Strong families of Thorpe Hall and to faithful members of the congregation. Below you will find: A.) A walk round tour with a plan and descriptions of items in the nave and chancel (* means there is more about this person or place in the second half of this history.) The nave and chancel have been divided into twelve sections corresponding to the numbers on the map. 1) The Children’s Corner 2) The organ area 3) The northwest window area 4) The North Aisle 5) The Horrell Window 6) The Chancel, north side 7) The Sanctuary Area 8) The Altar Rail 9) The Chancel, south side 10) The Gaskell brass plaques 11) Memorials to the Thorpe Hall families 12) The memorial book and board; the font B) The history of St Botolph, this church and families connected to it 1) St Botolph 2) The de Thorpe Family, the church and Longthorpe Tower 3) History of the church 4) The Thorpe Hall connection: the St Johns and Strongs 5) Father O-Reilly; the Oxford Movement A WALK ROUND THE CHURCH This guide takes you round the church in a clockwise direction. -

Revised-Office of the Dead in English Books of Hours

?41 ;225/1 ;2 ?41 01-0 59 1937-90+ 58-31 -90 8@>5/ 59 ?41 .;;6 ;2 4;@=> -90 =17-?10 ?1A?>! /# &')%"/# &)%% >BQBI >DIFLL - ?IFRJR >TCMJSSFE GOQ SIF 0FHQFF OG <I0 BS SIF @NJUFQRJSX OG >S# -NEQFVR '%&& 2TLL MFSBEBSB GOQ SIJR JSFM JR BUBJLBCLF JN =FRFBQDI,>S-NEQFVR+2TLL?FWS BS+ ISSP+$$QFRFBQDI"QFPORJSOQX#RS"BNEQFVR#BD#TK$ <LFBRF TRF SIJR JEFNSJGJFQ SO DJSF OQ LJNK SO SIJR JSFM+ ISSP+$$IEL#IBNELF#NFS$&%%'($'&%* ?IJR JSFM JR PQOSFDSFE CX OQJHJNBL DOPXQJHIS THE OFFICE OF THE DEAD IN ENGLAND: IMAGE AND MUSIC IN THE BOOK OF HOURS AND RELATED TEXTS, C. 1250- C. 1500 SARAH SCHELL SUBMITTED FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY SCHOOL OF ART HISTORY, UNIVERSITY OF ST ANDREWS DECEMBER, 2009 1 ABSTRACT This study examines the illustrations that appear at the Office of the Dead in English Books of Hours, and seeks to understand how text and image work together in this thriving culture of commemoration to say something about how the English understood and thought about death in the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries. The Office of the Dead would have been one of the most familiar liturgical rituals in the medieval period, and was recited almost without ceasing at family funerals, gild commemorations, yearly minds, and chantry chapel services. The Placebo and Dirige were texts that many people knew through this constant exposure, and would have been more widely known than other 'death' texts such as the Ars Moriendi. The images that are found in these books reflect wider trends in the piety and devotional practice of the time.