Effect of Temperature on Embryonic Development of Two Freshwater Pulmonates, Planorbarius Comeus (L.) and Planorbis Planorbis (L.)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Diversity of Echinostomes (Digenea: Echinostomatidae) in Their Snail Hosts at High Latitudes

Parasite 28, 59 (2021) Ó C. Pantoja et al., published by EDP Sciences, 2021 https://doi.org/10.1051/parasite/2021054 urn:lsid:zoobank.org:pub:9816A6C3-D479-4E1D-9880-2A7E1DBD2097 Available online at: www.parasite-journal.org RESEARCH ARTICLE OPEN ACCESS Diversity of echinostomes (Digenea: Echinostomatidae) in their snail hosts at high latitudes Camila Pantoja1,2, Anna Faltýnková1,* , Katie O’Dwyer3, Damien Jouet4, Karl Skírnisson5, and Olena Kudlai1,2 1 Institute of Parasitology, Biology Centre of the Czech Academy of Sciences, Branišovská 31, 370 05 České Budějovice, Czech Republic 2 Institute of Ecology, Nature Research Centre, Akademijos 2, 08412 Vilnius, Lithuania 3 Marine and Freshwater Research Centre, Galway-Mayo Institute of Technology, H91 T8NW, Galway, Ireland 4 BioSpecT EA7506, Faculty of Pharmacy, University of Reims Champagne-Ardenne, 51 rue Cognacq-Jay, 51096 Reims Cedex, France 5 Laboratory of Parasitology, Institute for Experimental Pathology, Keldur, University of Iceland, IS-112 Reykjavík, Iceland Received 26 April 2021, Accepted 24 June 2021, Published online 28 July 2021 Abstract – The biodiversity of freshwater ecosystems globally still leaves much to be discovered, not least in the trematode parasite fauna they support. Echinostome trematode parasites have complex, multiple-host life-cycles, often involving migratory bird definitive hosts, thus leading to widespread distributions. Here, we examined the echinostome diversity in freshwater ecosystems at high latitude locations in Iceland, Finland, Ireland and Alaska (USA). We report 14 echinostome species identified morphologically and molecularly from analyses of nad1 and 28S rDNA sequence data. We found echinostomes parasitising snails of 11 species from the families Lymnaeidae, Planorbidae, Physidae and Valvatidae. -

Liste Rouge Mollusques (Gastéropodes Et Bivalves)

2012 > L’environnement pratique > Listes rouges / Gestion des espèces > Liste rouge Mollusques (gastéropodes et bivalves) Espèces menacées en Suisse, état 2010 > L’environnement pratique > Listes rouges / Gestion des espèces > Liste rouge Mollusques (gastéropodes et bivalves) Espèces menacées en Suisse, état 2010 Publié par l’Office fédéral de l’environnement OFEV et par le Centre suisse de cartographie de la faune CSCF Berne, 2012 Valeur juridique de cette publication Impressum Liste rouge de l’OFEV au sens de l’art. 14, al. 3, de l’ordonnance Editeurs du 16 janvier 1991 sur la protection de la nature et du paysage Office fédéral de l’environnement (OFEV) (OPN; RS 451.1), www.admin.ch/ch/f/rs/45.html L’OFEV est un office du Département fédéral de l’environnement, des transports, de l’énergie et de la communication (DETEC). La présente publication est une aide à l’exécution de l’OFEV en tant Centre Suisse de Cartographie de la Faune (CSCF), Neuchâtel. qu’autorité de surveillance. Destinée en premier lieu aux autorités d’exécution, elle concrétise des notions juridiques indéterminées Auteurs provenant de lois et d’ordonnances et favorise ainsi une application Mollusques terrestres: Jörg Rüetschi, Peter Müller et François Claude uniforme de la législation. Elle aide les autorités d’exécution Mollusques aquatiques: Pascal Stucki et Heinrich Vicentini notamment à évaluer si un biotope doit être considéré comme digne avec la collaboration de Simon Capt et Yves Gonseth (CSCF) de protection (art. 14, al. 3, let. d, OPN). Accompagnement à l’OFEV Francis Cordillot, division Espèces, écosystèmes, paysages Référence bibliographique Rüetschi J., Stucki P., Müller P., Vicentini H., Claude F. -

December 2011

Ellipsaria Vol. 13 - No. 4 December 2011 Newsletter of the Freshwater Mollusk Conservation Society Volume 13 – Number 4 December 2011 FMCS 2012 WORKSHOP: Incorporating Environmental Flows, 2012 Workshop 1 Climate Change, and Ecosystem Services into Freshwater Mussel Society News 2 Conservation and Management April 19 & 20, 2012 Holiday Inn- Athens, Georgia Announcements 5 The FMCS 2012 Workshop will be held on April 19 and 20, 2012, at the Holiday Inn, 197 E. Broad Street, in Athens, Georgia, USA. The topic of the workshop is Recent “Incorporating Environmental Flows, Climate Change, and Publications 8 Ecosystem Services into Freshwater Mussel Conservation and Management”. Morning and afternoon sessions on Thursday will address science, policy, and legal issues Upcoming related to establishing and maintaining environmental flow recommendations for mussels. The session on Friday Meetings 8 morning will consider how to incorporate climate change into freshwater mussel conservation; talks will range from an overview of national and regional activities to local case Contributed studies. The Friday afternoon session will cover the Articles 9 emerging science of “Ecosystem Services” and how this can be used in estimating the value of mussel conservation. There will be a combined student poster FMCS Officers 47 session and social on Thursday evening. A block of rooms will be available at the Holiday Inn, Athens at the government rate of $91 per night. In FMCS Committees 48 addition, there are numerous other hotels in the vicinity. More information on Athens can be found at: http://www.visitathensga.com/ Parting Shot 49 Registration and more details about the workshop will be available by mid-December on the FMCS website (http://molluskconservation.org/index.html). -

Invertebrate Animals (Metazoa: Invertebrata) of the Atanasovsko Lake, Bulgaria

Historia naturalis bulgarica, 22: 45-71, 2015 Invertebrate Animals (Metazoa: Invertebrata) of the Atanasovsko Lake, Bulgaria Zdravko Hubenov, Lyubomir Kenderov, Ivan Pandourski Abstract: The role of the Atanasovsko Lake for storage and protection of the specific faunistic diversity, characteristic of the hyper-saline lakes of the Bulgarian seaside is presented. The fauna of the lake and surrounding waters is reviewed, the taxonomic diversity and some zoogeographical and ecological features of the invertebrates are analyzed. The lake system includes from freshwater to hyper-saline basins with fast changing environment. A total of 6 types, 10 classes, 35 orders, 82 families and 157 species are known from the Atanasovsko Lake and the surrounding basins. They include 56 species (35.7%) marine and marine-brackish forms and 101 species (64.3%) brackish-freshwater, freshwater and terrestrial forms, connected with water. For the first time, 23 species in this study are established (12 marine, 1 brackish and 10 freshwater). The marine and marine- brackish species have 4 types of ranges – Cosmopolitan, Atlantic-Indian, Atlantic-Pacific and Atlantic. The Atlantic (66.1%) and Cosmopolitan (23.2%) ranges that include 80% of the species, predominate. Most of the fauna (over 60%) has an Atlantic-Mediterranean origin and represents an impoverished Atlantic-Mediterranean fauna. The freshwater-brackish, freshwater and terrestrial forms, connected with water, that have been established from the Atanasovsko Lake, have 2 main types of ranges – species, distributed in the Palaearctic and beyond it and species, distributed only in the Palaearctic. The representatives of the first type (52.4%) predomi- nate. They are related to the typical marine coastal habitats, optimal for the development of certain species. -

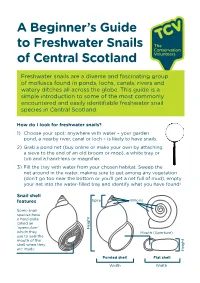

Freshwater Snail Guide

A Beginner’s Guide to Freshwater Snails of Central Scotland Freshwater snails are a diverse and fascinating group of molluscs found in ponds, lochs, canals, rivers and watery ditches all across the globe. This guide is a simple introduction to some of the most commonly encountered and easily identifiable freshwater snail species in Central Scotland. How do I look for freshwater snails? 1) Choose your spot: anywhere with water – your garden pond, a nearby river, canal or loch – is likely to have snails. 2) Grab a pond net (buy online or make your own by attaching a sieve to the end of an old broom or mop), a white tray or tub and a hand-lens or magnifier. 3) Fill the tray with water from your chosen habitat. Sweep the net around in the water, making sure to get among any vegetation (don’t go too near the bottom or you’ll get a net full of mud), empty your net into the water-filled tray and identify what you have found! Snail shell features Spire Whorls Some snail species have a hard plate called an ‘operculum’ Height which they Mouth (Aperture) use to seal the mouth of the shell when they are inside Height Pointed shell Flat shell Width Width Pond Snails (Lymnaeidae) Variable in size. Mouth always on right-hand side, shells usually long and pointed. Great Pond Snail Common Pond Snail Lymnaea stagnalis Radix balthica Largest pond snail. Common in ponds Fairly rounded and ’fat’. Common in weedy lakes, canals and sometimes slow river still waters. pools. -

Folk Taxonomy, Nomenclature, Medicinal and Other Uses, Folklore, and Nature Conservation Viktor Ulicsni1* , Ingvar Svanberg2 and Zsolt Molnár3

Ulicsni et al. Journal of Ethnobiology and Ethnomedicine (2016) 12:47 DOI 10.1186/s13002-016-0118-7 RESEARCH Open Access Folk knowledge of invertebrates in Central Europe - folk taxonomy, nomenclature, medicinal and other uses, folklore, and nature conservation Viktor Ulicsni1* , Ingvar Svanberg2 and Zsolt Molnár3 Abstract Background: There is scarce information about European folk knowledge of wild invertebrate fauna. We have documented such folk knowledge in three regions, in Romania, Slovakia and Croatia. We provide a list of folk taxa, and discuss folk biological classification and nomenclature, salient features, uses, related proverbs and sayings, and conservation. Methods: We collected data among Hungarian-speaking people practising small-scale, traditional agriculture. We studied “all” invertebrate species (species groups) potentially occurring in the vicinity of the settlements. We used photos, held semi-structured interviews, and conducted picture sorting. Results: We documented 208 invertebrate folk taxa. Many species were known which have, to our knowledge, no economic significance. 36 % of the species were known to at least half of the informants. Knowledge reliability was high, although informants were sometimes prone to exaggeration. 93 % of folk taxa had their own individual names, and 90 % of the taxa were embedded in the folk taxonomy. Twenty four species were of direct use to humans (4 medicinal, 5 consumed, 11 as bait, 2 as playthings). Completely new was the discovery that the honey stomachs of black-coloured carpenter bees (Xylocopa violacea, X. valga)were consumed. 30 taxa were associated with a proverb or used for weather forecasting, or predicting harvests. Conscious ideas about conserving invertebrates only occurred with a few taxa, but informants would generally refrain from harming firebugs (Pyrrhocoris apterus), field crickets (Gryllus campestris) and most butterflies. -

Species Distinction and Speciation in Hydrobioid Gastropoda: Truncatelloidea)

Andrzej Falniowski, Archiv Zool Stud 2018, 1: 003 DOI: 10.24966/AZS-7779/100003 HSOA Archives of Zoological Studies Review inhabit brackish water habitats, some other rivers and lakes, but vast Species Distinction and majority are stygobiont, inhabiting springs, caves and interstitial hab- itats. Nearly nothing is known about the biology and ecology of those Speciation in Hydrobioid stygobionts. Much more than 1,000 nominal species have been de- Mollusca: Caeno- scribed (Figure 1). However, the real number of species is not known, Gastropods ( in fact. Not only because of many species to be discovered in the fu- gastropoda ture, but mostly since there are no reliable criteria, how to distinguish : Truncatelloidea) a species within the group. Andrzej Falniowski* Department of Malacology, Institute of Zoology and Biomedical Research, Jagiellonian University, Poland Abstract Hydrobioids, known earlier as the family Hydrobiidae, represent a set of truncatelloidean families whose members are minute, world- wide distributed snails inhabiting mostly springs and interstitial wa- ters. More than 1,000 nominal species bear simple plesiomorphic shells, whose variability is high and overlapping between the taxa, and the soft part morphology and anatomy of the group is simplified because of miniaturization, and unified, as a result of necessary ad- aptations to the life in freshwater habitats (osmoregulation, internal fertilization and eggs rich in yolk and within the capsules). The ad- aptations arose parallel, thus represent homoplasies. All the above facts make it necessary to use molecular markers in species dis- crimination, although this should be done carefully, considering ge- netic distances calibrated at low taxonomic level. There is common Figure 1: Shells of some of the European representatives of Truncatelloidea: A believe in crucial place of isolation as a factor shaping speciation in - Ecrobia, B - Pyrgula, C-D - Dianella, E - Adrioinsulana, F - Pseudamnicola, G long-lasting completely isolated habitats. -

2011 Biodiversity Snapshot. Isle of Man Appendices

UK Overseas Territories and Crown Dependencies: 2011 Biodiversity snapshot. Isle of Man: Appendices. Author: Elizabeth Charter Principal Biodiversity Officer (Strategy and Advocacy). Department of Environment, Food and Agriculture, Isle of man. More information available at: www.gov.im/defa/ This section includes a series of appendices that provide additional information relating to that provided in the Isle of Man chapter of the publication: UK Overseas Territories and Crown Dependencies: 2011 Biodiversity snapshot. All information relating to the Isle or Man is available at http://jncc.defra.gov.uk/page-5819 The entire publication is available for download at http://jncc.defra.gov.uk/page-5821 1 Table of Contents Appendix 1: Multilateral Environmental Agreements ..................................................................... 3 Appendix 2 National Wildife Legislation ......................................................................................... 5 Appendix 3: Protected Areas .......................................................................................................... 6 Appendix 4: Institutional Arrangements ........................................................................................ 10 Appendix 5: Research priorities .................................................................................................... 13 Appendix 6 Ecosystem/habitats ................................................................................................... 14 Appendix 7: Species .................................................................................................................... -

The Genus Bilharziella Vs. Other Bird Schistosomes in Snail Hosts from One of the Major Recreational Lakes in Poland

Knowl. Manag. Aquat. Ecosyst. 2021, 422, 12 Knowledge & © A. Stanicka et al., Published by EDP Sciences 2021 Management of Aquatic https://doi.org/10.1051/kmae/2021013 Ecosystems Journal fully supported by Office www.kmae-journal.org français de la biodiversité RESEARCH PAPER The genus Bilharziella vs. other bird schistosomes in snail hosts from one of the major recreational lakes in Poland Anna Stanicka1,*, Łukasz Migdalski1, Kamila Stefania Zając2, Anna Cichy1, Dorota Lachowska-Cierlik3 and Elzbieta_ Żbikowska1 1 Faculty of Biological and Veterinary Sciences, Department of Invertebrate Zoology and Parasitology, Nicolaus Copernicus University in Torun, Lwowska 1, 87-100 Torun, Poland 2 Institute of Environmental Sciences, Jagiellonian University, Gronostajowa 7, 30-387 Krakow, Poland 3 Institute of Zoology and Biomedical Research, Jagiellonian University, Gronostajowa 9, 30-387 Krakow, Poland Received: 3 November 2020 / Accepted: 4 March 2021 Abstract – Bird schistosomes are commonly established as the causative agent of swimmer’s itch À a hyper- sensitive skin reaction to the penetration of their infective larvae. The aim of the present study was to investigate the prevalence of the genus Bilharziella in comparison to other bird schistosome species from Lake Drawsko À one of the largest recreational lakes in Poland, struggling with the huge problem of swimmer’s itch. In total, 317 specimens of pulmonate snails were collected and examined. The overall digenean infection was 35.33%. The highest bird schistosome prevalence was observed for Bilharziella sp. (4.63%) in Planorbarius corneus, followed by Trichobilharzia szidati (3.23%) in Lymnaea stagnalis and Trichobilharzia sp. (1.3%) in Stagnicola palustris. The location of Bilharziella sp. -

The Interactive Effects of Predators, Resources, and Disturbance On

Florida International University FIU Digital Commons FIU Electronic Theses and Dissertations University Graduate School 4-23-2010 The nI teractive Effects of Predators, Resources, and Disturbance on Freshwater Snail Populations from the Everglades Clifton B. Ruehl Florida International University, [email protected] DOI: 10.25148/etd.FI10080412 Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.fiu.edu/etd Part of the Biology Commons, Other Ecology and Evolutionary Biology Commons, Population Biology Commons, and the Terrestrial and Aquatic Ecology Commons Recommended Citation Ruehl, Clifton B., "The nI teractive Effects of Predators, Resources, and Disturbance on Freshwater Snail Populations from the Everglades" (2010). FIU Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 266. https://digitalcommons.fiu.edu/etd/266 This work is brought to you for free and open access by the University Graduate School at FIU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in FIU Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of FIU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FLORIDA INTERNATIONAL UNIVERSITY Miami, Florida THE INTERACTIVE EFFECTS OF PREDATORS, RESOURCES, AND DISTURBANCE ON FRESHWATER SNAIL POPULATIONS FROM THE EVERGLADES A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in BIOLOGY by Clifton Benjamin Ruehl 2010 To: Dean Kenneth Furton choose the name of dean of your college/school College of Arts and Sciences choose the name of your college/school This dissertation, written by Clifton Benjamin Ruehl, and entitled The Interactive Effects of Predators, Resources, and Disturbance on Freshwater Snail Populations from the Everglades, having been approved in respect to style and intellectual content, is referred to you for judgment. -

Rote Liste Weichtiere (Schnecken Und Muscheln)

2012 > Umwelt-Vollzug > Rote Listen / Artenmanagement > Rote Liste Weichtiere (Schnecken und Muscheln) Gefährdete Arten der Schweiz, Stand 2010 > Umwelt-Vollzug > Rote Listen / Artenmanagement > Rote Liste Weichtiere (Schnecken und Muscheln) Gefährdete Arten der Schweiz, Stand 2010 Herausgegeben vom Bundesamt für Umwelt BAFU und vom Schweizer Zentrum für die Kartografie der Fauna SZKF/CSCF Bern, 2012 Rechtlicher Stellenwert dieser Publikation Impressum Rote Liste des BAFU im Sinne von Artikel 14 Absatz 3 der Verordnung Herausgeber vom 16. Januar 1991 über den Natur- und Heimatschutz (NHV; Bundesamt für Umwelt (BAFU) des Eidg. Departements für Umwelt, SR 451.1) www.admin.ch/ch/d/sr/45.html Verkehr, Energie und Kommunikation (UVEK), Bern. Schweizerisches Zentrum für die Kartografie der Fauna (SZKF/CSCF), Diese Publikation ist eine Vollzugshilfe des BAFU als Aufsichtsbehörde Neuenburg. und richtet sich primär an die Vollzugsbehörden. Sie konkretisiert unbestimmte Rechtsbegriffe von Gesetzen und Verordnungen und soll Autoren eine einheitliche Vollzugspraxis fördern. Sie dient den Vollzugs- Landschnecken: Jörg Rüetschi, Peter Müller und François Claude behörden insbesondere dazu, zu beurteilen, ob Biotope als schützens- Wassermollusken: Pascal Stucki und Heinrich Vicentini wert zu bezeichnen sind (Art. 14 Abs. 3 Bst. d NHV). in Zusammenarbeit mit Simon Capt und Yves Gonseth (CSCF) Begleitung BAFU Francis Cordillot, Abteilung Arten, Ökosysteme, Landschaften Zitierung Rüetschi J., Stucki P., Müller P., Vicentini H., Claude F. 2012: Rote Liste -

Mollusca) 263-272 © Biologiezentrum Linz/Austria; Download Unter

ZOBODAT - www.zobodat.at Zoologisch-Botanische Datenbank/Zoological-Botanical Database Digitale Literatur/Digital Literature Zeitschrift/Journal: Linzer biologische Beiträge Jahr/Year: 2003 Band/Volume: 0035_1 Autor(en)/Author(s): Mitov Plamen Genkov, Dedov Ivailo K., Stoyanov Ivailo Artikel/Article: Teratological data on Bulgarian Gastropoda (Mollusca) 263-272 © Biologiezentrum Linz/Austria; download unter www.biologiezentrum.at Linzer biol. Beitr. 35/1 263-272 30.6.2003 Teratological data on Bulgarian Gastropoda (Mollusca) P. MlTOV, I. DEDOV & I. STOYANOV Abstract: During faunistic investigations in diverse regions of Bulgaria, 8 gastropod specimens (6 species) with diverse morphological anomalies of the shell and body were found. These include specimens of: 1) Rapana venosa (VALENCIENNES 1846) with atypical, high-conic (scalarid) shells; 2) Planorbis planorbis (LINNAEUS 1758) with an aberrantly (deviation from the coiling surface) coiled shell; 3) Stagnicola palustris (O. F. MÜLLER 1774) with an entirely uncoiled shell; 4) Laciniaria plicata (DRAPARNAUD 1801) with abnormally uncoiled last whorl accompanied with a bend of the axis of the shell spires; 5) Umax {Umax) punctulatus SORDELLI 1870 with an abnormal formation of the posterior part of foot; and 6) Helix pomatia rhodopensis KOBELT 1906 with an oddly shaped ommathophore. These observations are attributed to mechanical injuries (traumatic or caused by parasite invasion trough the mantle), genetic anomalies, atavisms, and regenerative processes. Key words: Gastropoda, anomalies, Bulgaria. Introduction In the malacological literature, many anomalies of the shell (ROSSMÄSSLER 1835, 1837, 1914, SIMROTH 1908, 1928, SLAVI'K 1869, ULICNY 1892, FRANKENBERGER 1912, GEYER 1927, KNIGHTA 1930, PETRBOK 1939, 1943, DUCHON 1943, SCHILDER & SCHILDER 1953 (after KOVANDA 1956), ROTARIDES & SCHLESCH 1951, KOVANDA 1956, JACKIEWICZ 1965, PETRUCCIOLI 1996 among others), the body (SIMROTH 1908 among others), and the radulae (BECK 1912 (after SIMROTH 1908), BOR et al.