Flowering Plants. Dicotyledons

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A New Species of Saurauia (Actinidiaceae) from Jharkhand State, India

J. Jpn. Bot. 84: 233–236 (2009) A New Species of Saurauia (Actinidiaceae) from Jharkhand State, India Vinay ranjan and S. C. srivastava Central National Herbarium, Botanical Survey of India Howrah–711103, INDIA E-mail: [email protected] (Received on November 25, 2008) Saurauia parasnathensis V. Ranjan & S. C. Srivastava is described from India as new to science. This species is characterized by having cymose inflorescence with many- flowered fascicles, yellow flowers and 27–35 stamens in two rows. Key words: Actinidiaceae, India, new species, Saurauia. Saurauia Willd., comprising of 300 27–35 stamens in two rows. species (Mabberley 2005), is distributed in tropical Asia and America (Cuong et al. 2007, Saurauia parasnathensis V. Ranjan & Dressler and Bayer 2004, Soejarto 2004). S. C. Srivastava, sp. nov. [Figs. 1, 2] Hooker (1874) and Paul (1993) described Specibus differt aliis Saurauia cerea eight species from British India and India, Dyer petalis flavis, inflorescentiae cymosae respectively. While collecting the materials for multifloris fasciculis et staminibus 27–35 flora of Parasnath Wildlife Sanctuary, Giridih bistratus ornata. District, Jharkhand State, India between Type: INDIA: Jharkhand State, Giridih 2004 and 2006, the first author collected District, Parasnath Wildlife Sanctuary, alt. an interesting tree species of ca.10 m high, ca.1200 m, 21 March 2005, Vinay Ranjan leafless in flowering during the month of 37947A (holotype–CAL), 37947B (isotype– March, on the hill top. A search of Indian CAL). herbaria and literature revealed that it belongs Trees up to 10 m high, branchlets to the genus Saurauia Willd. (Actinidiaceae), brownish-black with ruptured bark and scars but the characters do not match with any of inflorescence. -

Taming the Wild Stewartia©

1 Boland-Tim-2019B-Taming-Stewartia Taming the Wild Stewartia© Timothy M. Boland and Todd J. Rounsaville Polly Hill Arboretum, 809 State Road, West Tisbury, Massachusetts 02575, USA [email protected] Keywords: Asexual propagation, native trees, plant collections, seeds, Stewartia SUMMARY The Polly Hill Arboretum (PHA) began working with native stewartia in 1967. Our founder, Polly Hill, was devoted to growing trees from seed. In 2006, the Polly Hill Arboretum was recognized as the Nationally Accredited Collection holder for stewartia. This status has guided our collection development, particularly on focused seed expeditions, which began in 2007. The PHA has been successful growing both species from seed, however, overwintering survival and transplanting of juvenile plants has proved more challenging. New insights into winter storage of seedlings is beginning to shed light on this problem. Experimentation with overwintering rooted cuttings has revealed that plants have preferred temperature and chilling requirements. These new overwintering protocols have thus far yielded positive results. Recent work with tissue culture has also shown promising results with both species. Future work includes grafting superior clones of our native stewartia onto Asiatic species in an effort to overcome the problematic issues of overwintering, transplantability, and better resistance to soil borne pathogens. Our Plant Collections Network (PCN) development plan outlines our next phase work with stewartia over the upcoming several years. The results of this work will be shared in future years as we continue to bring these exceptional small flowering trees into commercial production. 2 INTRODUCTION The commitment to building Polly Hill Arboretum’s (PHA) stewartia collection is based on our founder Polly Hill’s history with the genus and our own desire to encourage the cultivation of these superb small-flowering trees in home gardens. -

A High-Quality Actinidia Chinensis (Kiwifruit) Genome Haolin Wu1,Taoma1,Minghuikang1,Fandiai1, Junlin Zhang1, Guanyong Dong2 and Jianquan Liu1,3

Wu et al. Horticulture Research (2019) 6:117 Horticulture Research https://doi.org/10.1038/s41438-019-0202-y www.nature.com/hortres ARTICLE Open Access A high-quality Actinidia chinensis (kiwifruit) genome Haolin Wu1,TaoMa1,MinghuiKang1,FandiAi1, Junlin Zhang1, Guanyong Dong2 and Jianquan Liu1,3 Abstract Actinidia chinensis (kiwifruit) is a perennial horticultural crop species of the Actinidiaceae family with high nutritional and economic value. Two versions of the A. chinensis genomes have been previously assembled, based mainly on relatively short reads. Here, we report an improved chromosome-level reference genome of A. chinensis (v3.0), based mainly on PacBio long reads and Hi-C data. The high-quality assembled genome is 653 Mb long, with 0.76% heterozygosity. At least 43% of the genome consists of repetitive sequences, and the most abundant long terminal repeats were further identified and account for 23.38% of our novel genome. It has clear improvements in contiguity, accuracy, and gene annotation over the two previous versions and contains 40,464 annotated protein-coding genes, of which 94.41% are functionally annotated. Moreover, further analyses of genetic collinearity revealed that the kiwifruit genome has undergone two whole-genome duplications: one affecting all Ericales families near the K-T extinction event and a recent genus-specific duplication. The reference genome presented here will be highly useful for further molecular elucidation of diverse traits and for the breeding of this horticultural crop, as well as evolutionary studies with related taxa. Introduction require improvement because of difficulties in assembling “ ” 1234567890():,; 1234567890():,; 1234567890():,; 1234567890():,; Kiwifruit (known as the king of fruits because of its the short reads into long contigs and scaffolds. -

Alphabetical Lists of the Vascular Plant Families with Their Phylogenetic

Colligo 2 (1) : 3-10 BOTANIQUE Alphabetical lists of the vascular plant families with their phylogenetic classification numbers Listes alphabétiques des familles de plantes vasculaires avec leurs numéros de classement phylogénétique FRÉDÉRIC DANET* *Mairie de Lyon, Espaces verts, Jardin botanique, Herbier, 69205 Lyon cedex 01, France - [email protected] Citation : Danet F., 2019. Alphabetical lists of the vascular plant families with their phylogenetic classification numbers. Colligo, 2(1) : 3- 10. https://perma.cc/2WFD-A2A7 KEY-WORDS Angiosperms family arrangement Summary: This paper provides, for herbarium cura- Gymnosperms Classification tors, the alphabetical lists of the recognized families Pteridophytes APG system in pteridophytes, gymnosperms and angiosperms Ferns PPG system with their phylogenetic classification numbers. Lycophytes phylogeny Herbarium MOTS-CLÉS Angiospermes rangement des familles Résumé : Cet article produit, pour les conservateurs Gymnospermes Classification d’herbier, les listes alphabétiques des familles recon- Ptéridophytes système APG nues pour les ptéridophytes, les gymnospermes et Fougères système PPG les angiospermes avec leurs numéros de classement Lycophytes phylogénie phylogénétique. Herbier Introduction These alphabetical lists have been established for the systems of A.-L de Jussieu, A.-P. de Can- The organization of herbarium collections con- dolle, Bentham & Hooker, etc. that are still used sists in arranging the specimens logically to in the management of historical herbaria find and reclassify them easily in the appro- whose original classification is voluntarily pre- priate storage units. In the vascular plant col- served. lections, commonly used methods are systema- Recent classification systems based on molecu- tic classification, alphabetical classification, or lar phylogenies have developed, and herbaria combinations of both. -

An Intergeneric Hybrid Between Franklinia Alatamaha and Gordonia

HORTSCIENCE 41(6):1386–1388. 2006. hybrids using F. alatamaha. Ackerman and Williams (1982) conducted extensive crosses · between F. alatamaha and Camellia L. spp. Gordlinia grandiflora (Theaceae): and produced two intergeneric hybrids, but their growth was weak and extremely slow. An Intergeneric Hybrid Between Ranney and colleagues (2003) reported suc- cessful hybridization between F. alatamaha Franklinia alatamaha and and Schima argentea Pritz. In 1974, Dr. Elwin Orton, Jr. successfully crossed G. lasianthus with F. alatamaha and produced 33 hybrids Gordonia lasianthus (Orton, 1977). Orton (1977) further reported Thomas G. Ranney1,2 that the seedlings grew vigorously during the Department of Horticultural Science, Mountain Horticultural Crops first growing season and that a number of them flowered the following year; however, Research and Extension Center, North Carolina State University, 455 all the plants eventually died, possibly be- Research Dr., Fletcher, NC 28732-9244 cause of some type of genetic incompatibility 1 or a pathogen (e.g., Phytophthora). Although Paul R. Fantz Orton’s report was somewhat discouraging, Department of Horticultural Science, Box 7603, North Carolina State hybridization between F. alatamaha and University, Raleigh, NC 27695-7609 G. lasianthus could potentially combine the cold hardiness of F. alatamaha with the ever- Additional index words. Gordonia alatamaha, Gordonia pubescens, distant hybridization, green foliage of G. lasianthus and broaden intergeneric hybridization, plant breeding, wide hybridization the genetic base for further breeding among Abstract. Franklinia alatamaha Bartr. ex Marshall represents a monotypic genus that was these genera. The objective of this report is originally discovered in Georgia, USA, but is now considered extinct in the wild and is to describe the history of and to validate new maintained only in cultivation. -

Kingdom Plantae

KIWIFRUIT Kingdom Plantae - Plants Subkingdom Tracheobionta - Vascular plants Superdivision Spermatophyta - Seed plants Division Magnoliophyta - Flowering plants Class Magnoliopsida - Dicotyledons Subclass Dilleniidae Order Theales Family Actinidiaceae - Chinese Gooseberry family Genus Actinidia Lindl. - Actinidia Species Actinidia Deliciosa - Kiwi Fruit Kiwi FACTS . Kiwi fruit gets its name from the kiwi bird, a flightless bird native to New Zealand. .Native to China where they called it the “macaque peach” . Contains just as much potassium as a banana. Useful for improving asthmatic conditions in children and preventing colon cancer. .Contain a protein dissolving enzyme called actinidin which can cause allergic reactions . Kiwi History Almost all kiwi fruit in commerce belong to a few cultivators of Actininidia deliciosa: Hayward, Chico, and Saanichton 12 which are almost all indistiguishable from each other First appeared in Southern China and is still considered its national fruit. Introduced to the western world in the beginning of the 20th century when missionaries from China brought them to New Zealand 1952 Kiwifruits were exported to New England 1958 the first kiwifruits were exported to California 1970 the first crop of kiwifruits were successfully harvested in California 1991 a new variety of golden kiwifruit was developed named Hort16A As of today the leading producers are Italy, New Zealand, Chile, France, Greece, Japan, and the USA Kiwi Cultivation Planted in a moderately sunny place and vines should be protected -

ACTINIDIACEAE 1. ACTINIDIA Lindley, Nat. Syst. Bot., Ed. 2, 439

ACTINIDIACEAE 猕猴桃科 mi hou tao ke Li Jianqiang (李建强)1, Li Xinwei (李新伟)1; Djaja Djendoel Soejarto2 Trees, shrubs, or woody vines. Leaves alternate, simple, shortly or long petiolate, not stipulate. Flowers bisexual or unisexual or plants polygamous or functionally dioecious, usually fascicled, cymose, or paniculate. Sepals (2 or 3 or)5, imbricate, rarely valvate. Petals (4 or)5, sometimes more, imbricate. Stamens 10 to numerous, distinct or adnate to base of petals, hypogynous; anthers 2- celled, versatile, dehiscing by apical pores or longitudinally. Ovary superior, disk absent, locules and carpels 3–5 or more; placentation axile; ovules anatropous with a single integument, 10 or more per locule; styles as many as carpels, distinct or connate (then only one style), generally persistent. Fruit a berry or leathery capsule. Seeds not arillate, with usually large embryos and abundant endosperm. Three genera and ca. 357 species: Asia and the Americas; three genera (one endemic) and 66 species (52 endemic) in China. Economically, kiwifruit (Actinidia chinensis var. deliciosa) is an important fruit, which originated in central China and is especially common along the Yangtze River (well known as yang-tao). Now, it is widely cultivated throughout the world. For additional information see the paper by X. W. Li, J. Q. Li, and D. D. Soejarto (Acta Phytotax. Sin. 45: 633–660. 2007). Liang Chou-fen, Chen Yong-chang & Wang Yu-sheng. 1984. Actinidiaceae (excluding Sladenia). In: Feng Kuo-mei, ed., Fl. Reipubl. Popularis Sin. 49(2): 195–301, 309–334. 1a. Trees or shrubs; flowers bisexual or plants functionally dioecious .................................................................................. 3. Saurauia 1b. -

No Slide Title

Birds Netting is an effective Sunburn of Clusters way to protect against bird damage Usually caused by clusters suddenly Early sunburn becoming exposed to sun due to loss (or Late sunburn removal) of leaves during hot weather Kiwiberries & kiwifruit Kiwiberries Actinidia arguta • Adapted to most regions of Oregon • Cold hardy; does need protection from frost in spring • Fruit vine ripen • Small fruit with tropical flavor notes • Skin is edible • Separate male and female plants (except some self- fertility for ‘Issai’) • Prune using same methods as kiwifruit Kiwiberry cultivars “Fuzzy” Kiwifruit Actinidia deliciosa Hayward Issai Ananasnaya • Adapted to warmer regions of western Oregon • Vine needs 225 to 240 frost-free days • Only hardy to 10o F • Very late (doesn’t vine ripen) • Pick just before heavy fall frost Ken’s Red • Large fruit. Skin covered with brown “fuzz” • Good, sweet flavor when ripened • Prune using same methods as kiwiberries Unripe vine ripe Dr. Bernadine Strik, Oregon State University 31 Cordons and Canes Cane Trunk & head of vine • Cordons are permanent parts of the vine • Plants are naturally supporting spurs or vining and are ideally fruiting canes trained to a single • Two cordons per vine trunk Cordon common in all training Head • Kiwifruit vines live for a systems long time so the trunk • Canes are “one-year-old” can get very large in – shoots that grew last diameter Trunk year • The “head” of the vine • Buds will be evident on is at the top of the these one-year-old canes trunk • Canes are selected and Dormant -

New Combinations in Actinidiaceae from China

New Combinations in Actinidiaceae from China Li Xin-Wei Herbarium (HIB), Wuhan Botanical Garden of Chinese Academy of Sciences, Wuhan 430074, People’s Republic of China; Graduate School of the Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100039, People’s Republic of China Li Jian-Qiang Herbarium (HIB), Wuhan Botanical Garden of Chinese Academy of Sciences, Wuhan 430074, People’s Republic of China. [email protected] (author for correspondence) Soejarto Djaja Djendoel College of Pharmacy, University of Illinois at Chicago, 833 S. Wood Street, Chicago, Illinois 60612, U.S.A. ABSTRACT . During the revision of Actinidiaceae for The taxonomy of Saurauia Willdenow is much less the Flora of China, two new combinations are confusing than that of Actinidia, although the trichome proposed, Actinidia fulvicoma var. cinerascens (C. F. and other characters exhibit considerable variation; Liang) J. Q. Li & D. D. Soejarto and Saurauia we recognize 13 species from China. polyneura var. paucinervis (C. F. Liang & Y. S. Wang) J. Q. Li & D. D. Soejarto. 1. Actinidia fulvicoma Hance, J. Bot. 23: 321. Key words: Actinidia, China, Guangxi, Saurauia, 1885. TYPE: China. Guangdong: Luo-Fu-Shan, Xizang. May 1883, B. C. Henry s.n. (holotype, K). 1a. Actinidia fulvicoma var. cinerascens (C. F. In the first comprehensive revision of Actinidia Liang) J. Q. Li & D. D. Soejarto, comb. nov. Lindley, Dunn recognized 24 species in four sections, Basionym: Actinidia cinerascens C. F. Liang, Fl. i.e., sections Ampulliferae Dunn, Leiocarpae Dunn, Reipubl. Popularis Sin. 49(2): 252–254, 320– Maculatae Dunn, and Vestitae Dunn (Dunn, 1911). 321. 1984. TYPE: China. Guangdong: Luofu Later, H. -

Techniques for Detecting Actinidia Resistance to Leafrollers

Horticultural Insects 51 TECHNIQUES FOR DETECTING ACTINIDIA RESISTANCE TO LEAFROLLERS C.E. MCKENNA1, S.J. DOBSON1 and P.G. CONNOLLY2 1HortResearch, No. 1 Rd., RD2, Te Puke, New Zealand 2HortResearch, Private Bag 92169, Auckland, New Zealand Corresponding author: [email protected] ABSTRACT Hayward and Hort16A kiwifruit are susceptible to attack by the brownheaded leafroller (BHLR), Ctenopseustis obliquana, but the incidence and severity of damage to Hayward can be twice that of Hort16A. Three bioassay techniques were tested for their ability to detect differences in the relative susceptibility of the two kiwifruit cultivars to BHLR larvae. No differences were detected when larvae were reared on artificial diets containing Hayward or Hort16A plant material. Signifi cantly more larvae survived when reared on Hayward versus Hort16A leaf discs. Caging larvae onto leaves and fruit resulted in significantly more damage to Hayward compared with Hort16A. Measuring larval survival after 21 days on leaf discs, or the incidence and severity of damage caused by larvae caged on leaves or fruit, are both potential techniques for screening Actinidia plant material for resistance to leafrollers. Keywords: leafrollers, kiwifruit, host plant resistance, selection tools. INTRODUCTION Leafroller caterpillars (Lepidoptera: Tortricidae) are the most damaging pests of kiwifruit in New Zealand. At least six species of leafroller can be found on kiwifruit vines including the brownheaded leafrollers (BHLR), Ctenopseustis obliquana (Walker) and C. herana (Felder and Rogenhofer); the greenheaded leafrollers (GHLR), Planotortrix excessana (Walker) and P. octo Dugdale; the blacklyre leafroller (BLLR), Cnephasia jactatana (Walker); and the lightbrown apple moth (LBAM), Epiphyas postvittana (Walker). All species are endemic with the exception of LBAM. -

Preparing the Shaanxi-Qinling Mountains Integrated Ecosystem Management Project (Cofinanced by the Global Environment Facility)

Technical Assistance Consultant’s Report Project Number: 39321 June 2008 PRC: Preparing the Shaanxi-Qinling Mountains Integrated Ecosystem Management Project (Cofinanced by the Global Environment Facility) Prepared by: ANZDEC Limited Australia For Shaanxi Province Development and Reform Commission This consultant’s report does not necessarily reflect the views of ADB or the Government concerned, and ADB and the Government cannot be held liable for its contents. (For project preparatory technical assistance: All the views expressed herein may not be incorporated into the proposed project’s design. FINAL REPORT SHAANXI QINLING BIODIVERSITY CONSERVATION AND DEMONSTRATION PROJECT PREPARED FOR Shaanxi Provincial Government And the Asian Development Bank ANZDEC LIMITED September 2007 CURRENCY EQUIVALENTS (as at 1 June 2007) Currency Unit – Chinese Yuan {CNY}1.00 = US $0.1308 $1.00 = CNY 7.64 ABBREVIATIONS ADB – Asian Development Bank BAP – Biodiversity Action Plan (of the PRC Government) CAS – Chinese Academy of Sciences CASS – Chinese Academy of Social Sciences CBD – Convention on Biological Diversity CBRC – China Bank Regulatory Commission CDA - Conservation Demonstration Area CNY – Chinese Yuan CO – company CPF – country programming framework CTF – Conservation Trust Fund EA – Executing Agency EFCAs – Ecosystem Function Conservation Areas EIRR – economic internal rate of return EPB – Environmental Protection Bureau EU – European Union FIRR – financial internal rate of return FDI – Foreign Direct Investment FYP – Five-Year Plan FS – Feasibility -

Phylogeny of Rosids! ! Rosids! !

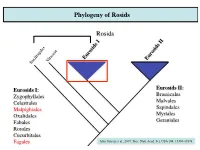

Phylogeny of Rosids! Rosids! ! ! ! ! Eurosids I Eurosids II Vitaceae Saxifragales Eurosids I:! Eurosids II:! Zygophyllales! Brassicales! Celastrales! Malvales! Malpighiales! Sapindales! Oxalidales! Myrtales! Fabales! Geraniales! Rosales! Cucurbitales! Fagales! After Jansen et al., 2007, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 104: 19369-19374! Phylogeny of Rosids! Rosids! ! ! ! ! Eurosids I Eurosids II Vitaceae Saxifragales Eurosids I:! Eurosids II:! Zygophyllales! Brassicales! Celastrales! Malvales! Malpighiales! Sapindales! Oxalidales! Myrtales! Fabales! Geraniales! Rosales! Cucurbitales! Fagales! After Jansen et al., 2007, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 104: 19369-19374! Alnus - alders A. rubra A. rhombifolia A. incana ssp. tenuifolia Alnus - alders Nitrogen fixation - symbiotic with the nitrogen fixing bacteria Frankia Alnus rubra - red alder Alnus rhombifolia - white alder Alnus incana ssp. tenuifolia - thinleaf alder Corylus cornuta - beaked hazel Carpinus caroliniana - American hornbeam Ostrya virginiana - eastern hophornbeam Phylogeny of Rosids! Rosids! ! ! ! ! Eurosids I Eurosids II Vitaceae Saxifragales Eurosids I:! Eurosids II:! Zygophyllales! Brassicales! Celastrales! Malvales! Malpighiales! Sapindales! Oxalidales! Myrtales! Fabales! Geraniales! Rosales! Cucurbitales! Fagales! After Jansen et al., 2007, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 104: 19369-19374! Fagaceae (Beech or Oak family) ! Fagaceae - 9 genera/900 species.! Trees or shrubs, mostly northern hemisphere, temperate region ! Leaves simple, alternate; often lobed, entire or serrate, deciduous