The Role of Education in Teaching Norms and Values

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

NKO) 2010 En 2012

Microdataservices Documentatierapport Nationaal Kiezers onderzoek (NKO) 2010 en 2012 Datum:24 januari 2017 19 april 2012 Microdataservices Bronvermelding Publicatie van uitkomsten geschiedt door de onderzoeksinstelling of de opdrachtgever op eigen titel. Verwijzing naar het CBS betreft uitsluitend het gebruik van de niet–openbare microdata. Deze microdata zijn onder bepaalde voorwaarden voor statistisch en wetenschappelijk onderzoek toegankelijk. Voor nadere informatie [email protected]. Dat wordt als volgt geformuleerd: “Resultaten [gedeeltelijk] gebaseerd op eigen berekeningen [naam onderzoeksinstelling, c.q. opdrachtgever] op basis van niet-openbare microdata van het Centraal Bureau voor de Statistiek betreffende het Nationaal Kiezers Onderzoek 2010 en 2012.” Engelse versie “Results based on calculations by [name of research institution or commissioning party] using non-public microdata from Statistics Netherlands.” “Under certain conditions, these microdata are accessible for statistical and scientific research. For further information: [email protected].“ . Documentatierapport NKO 2010-2012 2 Microdataservices Beschikbare bestand(en): NKO2010V1; NKO2012V1 In de Versiegeschiedenis wordt een chronologisch overzicht gegeven over dit onderwerp. De gebruiker dient rekening te houden met het volgende: Voor de persoonskenmerken en/of achtergronden dient u de beschikbare GBA- bestanden te raadplegen. Deze staan bij Zelf onderzoek doen in de catalogus onder het thema Bevolking. Voor het aanvragen van deze bestanden geldt de gebruikelijke procedure. -

THE NETHERLANDS and Literature Survey

Muslims in the EU: Cities Report Preliminary research report THE NETHERLANDS and literature survey 2007 Researchers: Froukje Demant (MA), Marcel Maussen (MA), Prof. Dr. Jan Rath Institute for Migration and Ethnic Studies (IMES) Open Society Institute Muslims in the EU - Cities Report EU Monitoring and Advocacy Program The Netherlands Table of contents Background............................................................................................................................... 5 Executive Summary ................................................................................................................. 6 Part I: Research and literature on Muslims .......................................................................... 9 1. Population ......................................................................................................................... 9 1.1 A note on the terminology and statistics ...................................................................... 9 1.2 Patterns of immigration.............................................................................................. 10 1.3 Citizenship.................................................................................................................. 13 2. Identity and religiosity................................................................................................... 14 2.1 Religosity.................................................................................................................... 14 2.2 Radicalisation of Muslim young -

Master Thesis Definitief

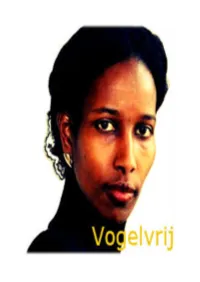

Vogelvrij Een onderzoek naar werkelijkheidsconstructies in het debat over de paspoortaffaire van Ayaan Hirsi Ali Project: MA-scriptie Film- en Televisiewetenschap Universiteit Utrecht Auteur: Linda Kloosterboer [email protected] 1ste begeleider: Dr. Rob Leurs [email protected] 2de begeleider: Dr. Judith Keilbach [email protected] Datum: Mei 2013 "The important thing is not to stop questioning. Curiosity has its own reason for existing." - Albert Einstein - Voorwoord Het is zover, voor u ligt mijn masterscriptie ´Vogelvrij’. Een onderzoek dat zich richt op het mediadebat dat losbrak nadat VARA onderzoeksjournalistiek programma ZEMBLA in mei 2006 de aflevering: ‘De Heilige Ayaan’ uitzond. Het doel van dit onderzoek is om meer inzicht te krijgen in werkelijkheidsconstructies, het ontstaan daarvan en de impact die het kan hebben op debatvoering in media, maatschappij en politiek. Twee jaar geleden ben ik met de casus in aanraking gekomen, toen ik research deed voor een interview met filmproducent René Mendel. Op de website van zijn productiemaatschappij was een trailer van de film: DE LEUGEN [2010] te zien. Na het bekijken van de trailer was ik meteen gefascineerd. Het verhaal rondom het vertrek van Ayaan Hirsi Ali, had alle elementen in zich van een fictieve dramafilm. Ware het niet dat de film gebaseerd was op gebeurtenissen die zich daadwerkelijk in 2006 hadden afgespeeld. Leugens die al eerder, in 2002, geopenbaard waren zorgden in 2006 voor een storm aan media-aandacht en leidde uiteindelijk tot de val van het kabinet Balkenende II. Hoe kon het dat leugens die al eerder in de openbaarheid waren gekomen, jaren later nog een dergelijke impact konden hebben? Het werd mijn missie hier verder inzicht in te krijgen. -

Justice and Home Affairs

14817/02 (Presse 375) 2469th Council meeting - JUSTICE AND HOME AFFAIRS - Brussels, 28 - 29 November 2002 Presidents : Ms Lene ESPERSEN Minister for Justice Mr Bertel HAARDER Minister for Refugees, Immigration and Integration and Minister without Portfolio with responsibility for European Affairs of the Kingdom of Denmark Internet: http://ue.eu.int/ E-mail: [email protected] For further information call 32 2 285 95 48 32 2 285 81 11 14817/02 (Presse 375) 1 EN 28.XI.2002 CONTENTS 1 PARTICIPANTS................................................................................................................................ 5 ITEMS DEBATED FOLLOW-UP TO THE SEVILLE CONCLUSIONS ......................................................................... 6 DETERMINATION OF THE MEMBER STATE RESPONSIBLE FOR EXAMINING AN ASYLUM APPLICATION (DUBLIN II) ........................................................................................... 7 READMISSION AGREEMENTS WITH THIRD-COUNTRIES...................................................... 8 QUALIFICATION AND STATUS OF THIRD-COUNTRY NATIONALS AND STATELESS PERSONS AS REFUGEES OR AS NEEDING INTERNATIONAL PROTECTION..................................................................................................................................... 8 MINIMUM STANDARDS FOR THE RECEPTION OF ASYLUM SEEKERS IN MEMBER STATES............................................................................................................................................... 9 RETURN ACTION PROGRAMME................................................................................................ -

Comparative Study of Electoral Systems Module 3

COMPARATIVE STUDY OF ELECTORAL SYSTEMS - MODULE 3 (2006-2011) CODEBOOK: APPENDICES Original CSES file name: cses2_codebook_part3_appendices.txt (Version: Full Release - December 15, 2015) GESIS Data Archive for the Social Sciences Publication (pdf-version, December 2015) ============================================================================================= COMPARATIVE STUDY OF ELECTORAL SYSTEMS (CSES) - MODULE 3 (2006-2011) CODEBOOK: APPENDICES APPENDIX I: PARTIES AND LEADERS APPENDIX II: PRIMARY ELECTORAL DISTRICTS FULL RELEASE - DECEMBER 15, 2015 VERSION CSES Secretariat www.cses.org =========================================================================== HOW TO CITE THE STUDY: The Comparative Study of Electoral Systems (www.cses.org). CSES MODULE 3 FULL RELEASE [dataset]. December 15, 2015 version. doi:10.7804/cses.module3.2015-12-15 These materials are based on work supported by the American National Science Foundation (www.nsf.gov) under grant numbers SES-0451598 , SES-0817701, and SES-1154687, the GESIS - Leibniz Institute for the Social Sciences, the University of Michigan, in-kind support of participating election studies, the many organizations that sponsor planning meetings and conferences, and the many organizations that fund election studies by CSES collaborators. Any opinions, findings and conclusions, or recommendations expressed in these materials are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the funding organizations. =========================================================================== IMPORTANT NOTE REGARDING FULL RELEASES: This dataset and all accompanying documentation is the "Full Release" of CSES Module 3 (2006-2011). Users of the Final Release may wish to monitor the errata for CSES Module 3 on the CSES website, to check for known errors which may impact their analyses. To view errata for CSES Module 3, go to the Data Center on the CSES website, navigate to the CSES Module 3 download page, and click on the Errata link in the gray box to the right of the page. -

University of Groningen Populisten in De Polder Lucardie, Anthonie

University of Groningen Populisten in de polder Lucardie, Anthonie; Voerman, Gerrit IMPORTANT NOTE: You are advised to consult the publisher's version (publisher's PDF) if you wish to cite from it. Please check the document version below. Document Version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Publication date: 2012 Link to publication in University of Groningen/UMCG research database Citation for published version (APA): Lucardie, P., & Voerman, G. (2012). Populisten in de polder. Meppel: Boom. Copyright Other than for strictly personal use, it is not permitted to download or to forward/distribute the text or part of it without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), unless the work is under an open content license (like Creative Commons). Take-down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Downloaded from the University of Groningen/UMCG research database (Pure): http://www.rug.nl/research/portal. For technical reasons the number of authors shown on this cover page is limited to 10 maximum. Download date: 10-02-2018 Paul lucardie & Gerrit Voerman Omslagontwerp: Studio Jan de Boer, Amsterdam Vormgeving binnenwerk: Velotekst (B.L. van Popering), Zoetermeer Druk:Wilco,Amersfoort © 2012 de auteurs Behoudens de in of krachtens de Auteurswet van 1912 gestelde uitzonderingen mag niets uit deze uitgave worden verveelvoudigd, opgeslagen in een geautomatiseerd gegevensbestand, of openbaar gemaakt, in enige vorm of op enige wijze, hetzij elektronisch, mechanisch door fotokopieën, opnamen of enig andere manier, zonder voorafgaande schriftelijke toestemming van de uitgever. -

De Erfenis Van Fortuyn

De erfenis van Fortuyn De parlementaire en politieke nalatenschap van Pim Fortuyn Redactie: Jan Schinkelshoek Careljan Rotteveel Mansveld Deel 1 van de Montesquieu-reeks Het Montesquieu Instituut is een multifunctioneel onderzoeks- en onderwijsinstituut voor vergelijkende parlementaire geschiedenis en constitutionele ontwikkeling in Europa. Het werkt samen met andere wetenschappelijke instellingen in Nederland en in Europa. Het streeft er naar om de beschikbare kennis op dit terrein via een elektronisch kennisuitwisselingsnetwerk - waar nodig - tijdig en hanteerbaar onder handbereik van ambtenaren, bestuurders, journalisten, politici, wetenschappers én belangstellende burgers te brengen. Partners van het Montesquieu Instituut zijn - de Campus Den Haag en de Faculteit der Rechtsgeleerdheid van de Universiteit Leiden - de Capaciteitsgroep Publiekrecht van de Universiteit Maastricht - het Centrum voor Parlementaire Geschiedenis verbonden aan de Radboud Universiteit Nijmegen - het Documentatiecentrum Nederlandse Politieke Partijen van de Rijksuniversiteit Groningen - het Parlementair Documentatie Centrum van de Universiteit Leiden. © 2012 Montesquieu Instituut, Den Haag Al het materiaal uit deze bundel mag zonder toestemming vooraf en zonder vergoeding gebruikt en gereproduceerd worden voorzover dat gebeurt voor niet-commerciële doeleinden. Bij dit gebruik dient recht te worden gedaan aan de context van het materiaal en dient de auteur, de titel van de bundel en het Montesquieu Instituut als bron vermeld te worden. Het is niet toegestaan de -

Jaarboek Parlementaire Geschiedenis 2002 Nieuwkomers in De Politiek

Jaarboek Parlementaire Geschiedenis 2002 Nieuwkomers in de politiek Jaarboek Parlementaire Geschiedenis Nieuwkomers in de politiek Redactie: C.C. van Baaien W. Breedveld J.W.L. Brouwer P.G.T.W. van Griensven J.J.M. Ramakers W.R Secker Centrum voor Parlementaire Geschiedenis, Nijmegen Sdu Uitgevers, Den Haag Foto omslag: Hollandse Hoogte Vormgeving omslag: Wim Zaat, Moerkapelle Zetwerk: Wil van Dam, Utrecht Druk en afwerking: A-D Druk BV, Zeist © 2002, Centrum voor Parlementaire Geschiedenis, Nijmegen Alle rechthebbenden van illustraties hebben wij getracht te achterhalen. Mocht u desondanks menen aanspraak te maken op een vergoeding, clan verzoeken wij u contact op te nemen met de uitgever. Niets uit deze uitgave mag worden verveelvoudigd en/of openbaar gemaakt door middel van druk, fotokopie, microfilm of op welke andere wijze dan ook zonder voorafgaande schriftelijke toestemming van de uitgever. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form, by print, photoprint, microfilm or any other means without written permission from the publisher. isbn 90 12 09574 3 issn 1566-5054 Inhoud Ten geleide 7 Artikelen 9 Paul Lucardie, Van profeten en zwepen, regeringspartners en volkstribunen. Een beschouwing over de opkomst en rol van nieuwe partijen in het Nederlandse poli tieke bestel 10 Koen Vossen, Dominees, rouwdouwers en klungels. Nieuwkomers in de Tweede Kamer 1918-1940 20 Marco Schikhof, Opkomst, ontvangst en ‘uitburgering’ van een nieuwe partij en een nieuwe politicus. Ds’ 70 en Wim Drees jr. 29 Anne Bos en Willem Breedveld, Verwarring en onvermogen. De pers, de politiek en de opkomst van Pim Fortuyn 39 Jos de Beus, Volksvertegenwoordigers van ver. -

Collectie Pim Fortuyn Audio-Visueel

Collectie Pim Fortuyn Audio-Visueel Verzameling van televisie- en radioopnamen van en over (de dood van) Pim Fortuyn en daaraan gerelateerde onderwerpen, opgenomen over de periode 6 mei 2002 - mei 2005 door LPF-aanhanger Henk Roos te Bunschoten-Spakenburg. Televisie 1 [1w.-1/2] Opnamen van 6 mei 2002, vanaf 18.25 uur: uitzendingen Extra Journaal / Twee Vandaag / NOS Journaal / NOS Actueel, 1 DVD. Betreft o.m.: reacties Wim Kok, politici, justitie; straatbeelden, opening condoleanceregister; laatste radiointerview, beelden aanslag. 2 [2w.-3/4] Opnamen van 6 mei 2002, vervolg DVD 1, uitzendingen NOS Actueel; NOS Late Nieuws, 1 DVD. Betreft o.m.: reacties Wim Kok, Klaas de Vries en Benk Korthals. 3 [3w.-5/6] Opnamen van 7 mei 2002, vanaf 07:00 uur: diverse uitzendingen NOS (Extra) Journaal / NOS Actueel, 1 DVD. Betreft o.m.: reacties Europese leiders, Harry Mens, J. 't Hoofd, Bram Peper, A. Koekoek, poltici, straatbeelden, overzicht Europese kranten, persconferentie Wim Kok en Mat Herben (LPF) 4 [4w.-7] Opnamen van 7 mei 2002, vanaf 12:00 uur: diverse uitzendingen NOS (Extra) Nieuws, 1 DVD. Betreft o.m.: persconferentie G.T. Hofstee (justitie) en M. Berndsen (politie) e.a., arrestatiefoto's Volkert van der G., persconferentie Wim Kok over doorgang verkiezingen, herdenking in Eerste Kamer, Gerrit Braks, Wim Kok, reacties: lijsttrekkers Jeltje van Nieuwenhoven, Mat Herben, Winnie de Jong, Jan Peter Balkenende, reacties: Willem Alexander en Maxima vanaf de Antillen, persconferentie Feyenoord, Ivo Opstelten en doorgaan van Europacupfinale, straatbeelden massaal bloemen leggen. 5 [5w.-8/9] Opnamen van 7 mei 2002, vanaf 18:00 uur: diverse uitzendingen Twee Vandaag / NOS Nieuws / NOS Sportjournaal, 1 DVD. -

Dorette Corbey Over De Harde Politieke Strijd in Europa Het Moet Schoner

# Rood 07dev. 21-11-2005 10:31 Pagina 1 RLedenblad van de Partijood van de Arbeid • 2e jaargang • nummer 7 • december 2005 Afscheid van Ruud Koole Het rapport Goed wonen: voor iedereen, van iedereen Let op: 9 en 10 december Het Congres Dorette Corbey over de harde politieke strijd in Europa Het moet schoner Dorette Corbey (48) is Europarlementariër Sterk en sociaal # Rood 07dev. 21-11-2005 10:31 Pagina 2 Op school vinden ze het de rode loper maar raar dat ze zoveel tijd De Rode Loper wordt uitgerold voor PvdA’ers die normaal gesproken achter in de politiek steekt, maar de schermen werken. Meestal willen ze dat ook graag. Voor een portret in bij de Jonge Socialisten (JS) Rood wordt deze keer een uitzondering gemaakt voor Isabelle Buhre, kan ze haar ei kwijt. Isabelle hoofdredacteur van Lava, het ledenblad van de JS. Buhre (16) is al sinds haar twaalfde actief lid. Sinds Tekst Maarten Jan Griethuysen Foto Tessa Posthuma de Boer kort is ze hoofdredacteur van Lava en steekt ze al haar vrije tijd in de JS. ‘Ik kom niet uit een rood nest’ Eigenlijk mag je pas lid worden van de Jonge Socialisten vanaf 14 jaar, maar Isabelle werd al actief bij haar lokale JS- Isabelle Buhre (16) wil afdeling op haar twaalfde. ‘Iedereen de Eerste Kamer in denkt altijd dat ik uit een rood nest kom, als ze horen dat ik zo jong al actief werd bij de PvdA, maar dat is niet waar. Ik ben me gaan interesseren in de politiek omdat ik de opkomst van Pim Fortuyn zo boeiend vond. -

Personalization of Political Newspaper Coverage: a Longitudinal Study in the Dutch Context Since 1950

Personalization of political newspaper coverage: a longitudinal study in the Dutch context since 1950 Ellis Aizenberg, Wouter van Atteveldt, Chantal van Son, Franz-Xaver Geiger VU University, Amsterdam This study analyses whether personalization in Dutch political newspaper coverage has increased since 1950. In spite of the assumption that personalization increased over time in The Netherlands, earlier studies on this phenomenon in the Dutch context led to a scattered image. Through automatic and manual content analyses and regression analyses this study shows that personalization did increase in The Netherlands during the last century, the changes toward that increase however, occurred earlier on than expected at first. This study also shows that the focus of reporting on politics is increasingly put on the politician as an individual, the coverage in which these politicians are mentioned however became more substantive and politically relevant. Keywords: Personalization, content analysis, political news coverage, individualization, privatization Introduction When personalization occurs a focus is put on politicians and party leaders as individuals. The context of the news coverage in which they are mentioned becomes more private as their love lives, upbringing, hobbies and characteristics of personal nature seem increasingly thoroughly discussed. An article published in 1984 in the Dutch newspaper De Telegraaf forms a good example here, where a horse race betting event, which is attended by several ministers accompanied by their wives and girlfriends is carefully discussed1. Nowadays personalization is a much-discussed phenomenon in the field of political communication. It can simply be seen as: ‘a process in which the political weight of the individual actor in the political process increases 1 Ererondje (17 juli 1984). -

Report on Intercountry Adoption

Report on Intercountry Adoption “All things of value are defenceless” Report on Intercountry Adoption “All things of value are defenceless” Committee on Lesbian Parenthood and Intercountry Adoption 29 may 2008 Chair N.A. Kalsbeek Members Prof. G.R. de Groot Prof. F. Juffer A.P. van der Linden E.C.C. Punselie E. Steendijk A.W.M. Willems Secretariat H. Lenters M.H.J. van Slooten-Benders H.A.T. Verleg The subtitle for this report has been taken from the works of the poet Lucebert Report on Intercountry Adoption - “All things of value are defenceless” Contents Preface 5 Summary and recommendations 7 1. Introduction 19 1.1 Remit 19 1.2 The best interests of the child 19 1.3 The interests of the biological parents 23 1.4 The interests of (prospective) adoptive parents 23 1.5 Content of this report 24 2. The vulnerability of the adoption process 25 2.1 Introduction 25 2.2 Reasons for the relatively limited number of foreign children eligible for adoption 25 2.3 Vulnerability of the process 27 2.4 When is intercountry adoption ethically responsible? 31 3. The adoption procedure 35 3.1 Introduction 35 3.2 The current situation in relation to checks on the adoption procedure 35 3.3 Intercountry adoption from non-Convention countries 36 3.3.1 Certificate of approval 36 3.3.2 Authorisation per country 38 3.3.3 Authority to issue a designation order 39 3.3.4 Mediation through private or independent adoption 40 3.3.5 The granting of provisional residence permits 43 3.4 Full and Simple adoption 44 3.4.1 Introduction 44 3.4.2 Conversion from simple to full adoption 47 3.5 The activities performed by the accredited bodies 48 3.5.1 Quality Framework 48 3.5.2 Minimum number of adoption mediations 49 3.5.3 Subsidisation of accredited bodies 50 3.6 Financial aspects of intercountry adoption 51 3.7 International supervision 52 3.8 Consequences of introducing stricter measures for assessment and supervision 53 4.