The Links Between Academic Research and Public Policies in the Field of Migration and Ethnic Relations: Selected National

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

NKO) 2010 En 2012

Microdataservices Documentatierapport Nationaal Kiezers onderzoek (NKO) 2010 en 2012 Datum:24 januari 2017 19 april 2012 Microdataservices Bronvermelding Publicatie van uitkomsten geschiedt door de onderzoeksinstelling of de opdrachtgever op eigen titel. Verwijzing naar het CBS betreft uitsluitend het gebruik van de niet–openbare microdata. Deze microdata zijn onder bepaalde voorwaarden voor statistisch en wetenschappelijk onderzoek toegankelijk. Voor nadere informatie [email protected]. Dat wordt als volgt geformuleerd: “Resultaten [gedeeltelijk] gebaseerd op eigen berekeningen [naam onderzoeksinstelling, c.q. opdrachtgever] op basis van niet-openbare microdata van het Centraal Bureau voor de Statistiek betreffende het Nationaal Kiezers Onderzoek 2010 en 2012.” Engelse versie “Results based on calculations by [name of research institution or commissioning party] using non-public microdata from Statistics Netherlands.” “Under certain conditions, these microdata are accessible for statistical and scientific research. For further information: [email protected].“ . Documentatierapport NKO 2010-2012 2 Microdataservices Beschikbare bestand(en): NKO2010V1; NKO2012V1 In de Versiegeschiedenis wordt een chronologisch overzicht gegeven over dit onderwerp. De gebruiker dient rekening te houden met het volgende: Voor de persoonskenmerken en/of achtergronden dient u de beschikbare GBA- bestanden te raadplegen. Deze staan bij Zelf onderzoek doen in de catalogus onder het thema Bevolking. Voor het aanvragen van deze bestanden geldt de gebruikelijke procedure. -

THE NETHERLANDS and Literature Survey

Muslims in the EU: Cities Report Preliminary research report THE NETHERLANDS and literature survey 2007 Researchers: Froukje Demant (MA), Marcel Maussen (MA), Prof. Dr. Jan Rath Institute for Migration and Ethnic Studies (IMES) Open Society Institute Muslims in the EU - Cities Report EU Monitoring and Advocacy Program The Netherlands Table of contents Background............................................................................................................................... 5 Executive Summary ................................................................................................................. 6 Part I: Research and literature on Muslims .......................................................................... 9 1. Population ......................................................................................................................... 9 1.1 A note on the terminology and statistics ...................................................................... 9 1.2 Patterns of immigration.............................................................................................. 10 1.3 Citizenship.................................................................................................................. 13 2. Identity and religiosity................................................................................................... 14 2.1 Religosity.................................................................................................................... 14 2.2 Radicalisation of Muslim young -

Master Thesis Definitief

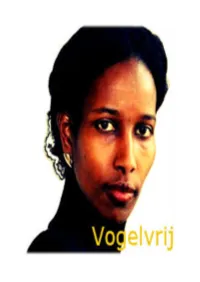

Vogelvrij Een onderzoek naar werkelijkheidsconstructies in het debat over de paspoortaffaire van Ayaan Hirsi Ali Project: MA-scriptie Film- en Televisiewetenschap Universiteit Utrecht Auteur: Linda Kloosterboer [email protected] 1ste begeleider: Dr. Rob Leurs [email protected] 2de begeleider: Dr. Judith Keilbach [email protected] Datum: Mei 2013 "The important thing is not to stop questioning. Curiosity has its own reason for existing." - Albert Einstein - Voorwoord Het is zover, voor u ligt mijn masterscriptie ´Vogelvrij’. Een onderzoek dat zich richt op het mediadebat dat losbrak nadat VARA onderzoeksjournalistiek programma ZEMBLA in mei 2006 de aflevering: ‘De Heilige Ayaan’ uitzond. Het doel van dit onderzoek is om meer inzicht te krijgen in werkelijkheidsconstructies, het ontstaan daarvan en de impact die het kan hebben op debatvoering in media, maatschappij en politiek. Twee jaar geleden ben ik met de casus in aanraking gekomen, toen ik research deed voor een interview met filmproducent René Mendel. Op de website van zijn productiemaatschappij was een trailer van de film: DE LEUGEN [2010] te zien. Na het bekijken van de trailer was ik meteen gefascineerd. Het verhaal rondom het vertrek van Ayaan Hirsi Ali, had alle elementen in zich van een fictieve dramafilm. Ware het niet dat de film gebaseerd was op gebeurtenissen die zich daadwerkelijk in 2006 hadden afgespeeld. Leugens die al eerder, in 2002, geopenbaard waren zorgden in 2006 voor een storm aan media-aandacht en leidde uiteindelijk tot de val van het kabinet Balkenende II. Hoe kon het dat leugens die al eerder in de openbaarheid waren gekomen, jaren later nog een dergelijke impact konden hebben? Het werd mijn missie hier verder inzicht in te krijgen. -

Justice and Home Affairs

14817/02 (Presse 375) 2469th Council meeting - JUSTICE AND HOME AFFAIRS - Brussels, 28 - 29 November 2002 Presidents : Ms Lene ESPERSEN Minister for Justice Mr Bertel HAARDER Minister for Refugees, Immigration and Integration and Minister without Portfolio with responsibility for European Affairs of the Kingdom of Denmark Internet: http://ue.eu.int/ E-mail: [email protected] For further information call 32 2 285 95 48 32 2 285 81 11 14817/02 (Presse 375) 1 EN 28.XI.2002 CONTENTS 1 PARTICIPANTS................................................................................................................................ 5 ITEMS DEBATED FOLLOW-UP TO THE SEVILLE CONCLUSIONS ......................................................................... 6 DETERMINATION OF THE MEMBER STATE RESPONSIBLE FOR EXAMINING AN ASYLUM APPLICATION (DUBLIN II) ........................................................................................... 7 READMISSION AGREEMENTS WITH THIRD-COUNTRIES...................................................... 8 QUALIFICATION AND STATUS OF THIRD-COUNTRY NATIONALS AND STATELESS PERSONS AS REFUGEES OR AS NEEDING INTERNATIONAL PROTECTION..................................................................................................................................... 8 MINIMUM STANDARDS FOR THE RECEPTION OF ASYLUM SEEKERS IN MEMBER STATES............................................................................................................................................... 9 RETURN ACTION PROGRAMME................................................................................................ -

Comparative Study of Electoral Systems Module 3

COMPARATIVE STUDY OF ELECTORAL SYSTEMS - MODULE 3 (2006-2011) CODEBOOK: APPENDICES Original CSES file name: cses2_codebook_part3_appendices.txt (Version: Full Release - December 15, 2015) GESIS Data Archive for the Social Sciences Publication (pdf-version, December 2015) ============================================================================================= COMPARATIVE STUDY OF ELECTORAL SYSTEMS (CSES) - MODULE 3 (2006-2011) CODEBOOK: APPENDICES APPENDIX I: PARTIES AND LEADERS APPENDIX II: PRIMARY ELECTORAL DISTRICTS FULL RELEASE - DECEMBER 15, 2015 VERSION CSES Secretariat www.cses.org =========================================================================== HOW TO CITE THE STUDY: The Comparative Study of Electoral Systems (www.cses.org). CSES MODULE 3 FULL RELEASE [dataset]. December 15, 2015 version. doi:10.7804/cses.module3.2015-12-15 These materials are based on work supported by the American National Science Foundation (www.nsf.gov) under grant numbers SES-0451598 , SES-0817701, and SES-1154687, the GESIS - Leibniz Institute for the Social Sciences, the University of Michigan, in-kind support of participating election studies, the many organizations that sponsor planning meetings and conferences, and the many organizations that fund election studies by CSES collaborators. Any opinions, findings and conclusions, or recommendations expressed in these materials are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the funding organizations. =========================================================================== IMPORTANT NOTE REGARDING FULL RELEASES: This dataset and all accompanying documentation is the "Full Release" of CSES Module 3 (2006-2011). Users of the Final Release may wish to monitor the errata for CSES Module 3 on the CSES website, to check for known errors which may impact their analyses. To view errata for CSES Module 3, go to the Data Center on the CSES website, navigate to the CSES Module 3 download page, and click on the Errata link in the gray box to the right of the page. -

University of Groningen Populisten in De Polder Lucardie, Anthonie

University of Groningen Populisten in de polder Lucardie, Anthonie; Voerman, Gerrit IMPORTANT NOTE: You are advised to consult the publisher's version (publisher's PDF) if you wish to cite from it. Please check the document version below. Document Version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Publication date: 2012 Link to publication in University of Groningen/UMCG research database Citation for published version (APA): Lucardie, P., & Voerman, G. (2012). Populisten in de polder. Meppel: Boom. Copyright Other than for strictly personal use, it is not permitted to download or to forward/distribute the text or part of it without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), unless the work is under an open content license (like Creative Commons). Take-down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Downloaded from the University of Groningen/UMCG research database (Pure): http://www.rug.nl/research/portal. For technical reasons the number of authors shown on this cover page is limited to 10 maximum. Download date: 10-02-2018 Paul lucardie & Gerrit Voerman Omslagontwerp: Studio Jan de Boer, Amsterdam Vormgeving binnenwerk: Velotekst (B.L. van Popering), Zoetermeer Druk:Wilco,Amersfoort © 2012 de auteurs Behoudens de in of krachtens de Auteurswet van 1912 gestelde uitzonderingen mag niets uit deze uitgave worden verveelvoudigd, opgeslagen in een geautomatiseerd gegevensbestand, of openbaar gemaakt, in enige vorm of op enige wijze, hetzij elektronisch, mechanisch door fotokopieën, opnamen of enig andere manier, zonder voorafgaande schriftelijke toestemming van de uitgever. -

De Erfenis Van Fortuyn

De erfenis van Fortuyn De parlementaire en politieke nalatenschap van Pim Fortuyn Redactie: Jan Schinkelshoek Careljan Rotteveel Mansveld Deel 1 van de Montesquieu-reeks Het Montesquieu Instituut is een multifunctioneel onderzoeks- en onderwijsinstituut voor vergelijkende parlementaire geschiedenis en constitutionele ontwikkeling in Europa. Het werkt samen met andere wetenschappelijke instellingen in Nederland en in Europa. Het streeft er naar om de beschikbare kennis op dit terrein via een elektronisch kennisuitwisselingsnetwerk - waar nodig - tijdig en hanteerbaar onder handbereik van ambtenaren, bestuurders, journalisten, politici, wetenschappers én belangstellende burgers te brengen. Partners van het Montesquieu Instituut zijn - de Campus Den Haag en de Faculteit der Rechtsgeleerdheid van de Universiteit Leiden - de Capaciteitsgroep Publiekrecht van de Universiteit Maastricht - het Centrum voor Parlementaire Geschiedenis verbonden aan de Radboud Universiteit Nijmegen - het Documentatiecentrum Nederlandse Politieke Partijen van de Rijksuniversiteit Groningen - het Parlementair Documentatie Centrum van de Universiteit Leiden. © 2012 Montesquieu Instituut, Den Haag Al het materiaal uit deze bundel mag zonder toestemming vooraf en zonder vergoeding gebruikt en gereproduceerd worden voorzover dat gebeurt voor niet-commerciële doeleinden. Bij dit gebruik dient recht te worden gedaan aan de context van het materiaal en dient de auteur, de titel van de bundel en het Montesquieu Instituut als bron vermeld te worden. Het is niet toegestaan de -

Jaarboek Parlementaire Geschiedenis 2002 Nieuwkomers in De Politiek

Jaarboek Parlementaire Geschiedenis 2002 Nieuwkomers in de politiek Jaarboek Parlementaire Geschiedenis Nieuwkomers in de politiek Redactie: C.C. van Baaien W. Breedveld J.W.L. Brouwer P.G.T.W. van Griensven J.J.M. Ramakers W.R Secker Centrum voor Parlementaire Geschiedenis, Nijmegen Sdu Uitgevers, Den Haag Foto omslag: Hollandse Hoogte Vormgeving omslag: Wim Zaat, Moerkapelle Zetwerk: Wil van Dam, Utrecht Druk en afwerking: A-D Druk BV, Zeist © 2002, Centrum voor Parlementaire Geschiedenis, Nijmegen Alle rechthebbenden van illustraties hebben wij getracht te achterhalen. Mocht u desondanks menen aanspraak te maken op een vergoeding, clan verzoeken wij u contact op te nemen met de uitgever. Niets uit deze uitgave mag worden verveelvoudigd en/of openbaar gemaakt door middel van druk, fotokopie, microfilm of op welke andere wijze dan ook zonder voorafgaande schriftelijke toestemming van de uitgever. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form, by print, photoprint, microfilm or any other means without written permission from the publisher. isbn 90 12 09574 3 issn 1566-5054 Inhoud Ten geleide 7 Artikelen 9 Paul Lucardie, Van profeten en zwepen, regeringspartners en volkstribunen. Een beschouwing over de opkomst en rol van nieuwe partijen in het Nederlandse poli tieke bestel 10 Koen Vossen, Dominees, rouwdouwers en klungels. Nieuwkomers in de Tweede Kamer 1918-1940 20 Marco Schikhof, Opkomst, ontvangst en ‘uitburgering’ van een nieuwe partij en een nieuwe politicus. Ds’ 70 en Wim Drees jr. 29 Anne Bos en Willem Breedveld, Verwarring en onvermogen. De pers, de politiek en de opkomst van Pim Fortuyn 39 Jos de Beus, Volksvertegenwoordigers van ver. -

Collectie Pim Fortuyn Audio-Visueel

Collectie Pim Fortuyn Audio-Visueel Verzameling van televisie- en radioopnamen van en over (de dood van) Pim Fortuyn en daaraan gerelateerde onderwerpen, opgenomen over de periode 6 mei 2002 - mei 2005 door LPF-aanhanger Henk Roos te Bunschoten-Spakenburg. Televisie 1 [1w.-1/2] Opnamen van 6 mei 2002, vanaf 18.25 uur: uitzendingen Extra Journaal / Twee Vandaag / NOS Journaal / NOS Actueel, 1 DVD. Betreft o.m.: reacties Wim Kok, politici, justitie; straatbeelden, opening condoleanceregister; laatste radiointerview, beelden aanslag. 2 [2w.-3/4] Opnamen van 6 mei 2002, vervolg DVD 1, uitzendingen NOS Actueel; NOS Late Nieuws, 1 DVD. Betreft o.m.: reacties Wim Kok, Klaas de Vries en Benk Korthals. 3 [3w.-5/6] Opnamen van 7 mei 2002, vanaf 07:00 uur: diverse uitzendingen NOS (Extra) Journaal / NOS Actueel, 1 DVD. Betreft o.m.: reacties Europese leiders, Harry Mens, J. 't Hoofd, Bram Peper, A. Koekoek, poltici, straatbeelden, overzicht Europese kranten, persconferentie Wim Kok en Mat Herben (LPF) 4 [4w.-7] Opnamen van 7 mei 2002, vanaf 12:00 uur: diverse uitzendingen NOS (Extra) Nieuws, 1 DVD. Betreft o.m.: persconferentie G.T. Hofstee (justitie) en M. Berndsen (politie) e.a., arrestatiefoto's Volkert van der G., persconferentie Wim Kok over doorgang verkiezingen, herdenking in Eerste Kamer, Gerrit Braks, Wim Kok, reacties: lijsttrekkers Jeltje van Nieuwenhoven, Mat Herben, Winnie de Jong, Jan Peter Balkenende, reacties: Willem Alexander en Maxima vanaf de Antillen, persconferentie Feyenoord, Ivo Opstelten en doorgaan van Europacupfinale, straatbeelden massaal bloemen leggen. 5 [5w.-8/9] Opnamen van 7 mei 2002, vanaf 18:00 uur: diverse uitzendingen Twee Vandaag / NOS Nieuws / NOS Sportjournaal, 1 DVD. -

Personalization of Political Newspaper Coverage: a Longitudinal Study in the Dutch Context Since 1950

Personalization of political newspaper coverage: a longitudinal study in the Dutch context since 1950 Ellis Aizenberg, Wouter van Atteveldt, Chantal van Son, Franz-Xaver Geiger VU University, Amsterdam This study analyses whether personalization in Dutch political newspaper coverage has increased since 1950. In spite of the assumption that personalization increased over time in The Netherlands, earlier studies on this phenomenon in the Dutch context led to a scattered image. Through automatic and manual content analyses and regression analyses this study shows that personalization did increase in The Netherlands during the last century, the changes toward that increase however, occurred earlier on than expected at first. This study also shows that the focus of reporting on politics is increasingly put on the politician as an individual, the coverage in which these politicians are mentioned however became more substantive and politically relevant. Keywords: Personalization, content analysis, political news coverage, individualization, privatization Introduction When personalization occurs a focus is put on politicians and party leaders as individuals. The context of the news coverage in which they are mentioned becomes more private as their love lives, upbringing, hobbies and characteristics of personal nature seem increasingly thoroughly discussed. An article published in 1984 in the Dutch newspaper De Telegraaf forms a good example here, where a horse race betting event, which is attended by several ministers accompanied by their wives and girlfriends is carefully discussed1. Nowadays personalization is a much-discussed phenomenon in the field of political communication. It can simply be seen as: ‘a process in which the political weight of the individual actor in the political process increases 1 Ererondje (17 juli 1984). -

Leaving the Netherlands

LEAVING THE NETHERLANDS Twenty years of voluntary return policy in the Netherlands (1989-2009) IOM P.O. Box 10796 2501 HT The Hague The Netherlands Ned 0/1/551 T 2010 10#539 IOM RApportomslag_NR03 A4_DEF.indd 1 06-12-2010 16:08:35 LEAVING THE NETHERLANDS Twenty years of voluntary return policy in the Netherlands (1989-2009) November 2010 Researchers Christian Mommers Evi Velthuis Editor Esther van Zadel Produced with a contribution of the European Return Fund Return. Not necessarily a step backward. IOM is committed to the principle that humane and orderly migration benefits migrants and society. As an intergovernmental body, IOM acts with its partners in the international community to assist in meeting the operational challenges of migration; advance understanding of migration issues; and uphold the human dignity and well-being of migrants. This research report is published within the framework of the project ‘(Re)assessing assisted voluntary return: the Netherlands in a European perspective’. The project was financed by the European Return Fund and the Dutch Ministry of Justice. Publisher: International Organization for Migration Mission in the Netherlands P.O. Box 10796 2501 HT The Hague The Netherlands Tel: +31 70 31 81 500 Fax: +31 70 33 85 454 E-mail: [email protected] Internet: www.iom-nederland.nl ISBN 978-92-9068-580-7 Copyright © 2010 International Organization for Migration (IOM) All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form by any means electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without prior written permission of the publisher. -

Lions of Tawhid in the Polder Paul Aarts and Fadi Hirzalla

Forensic researchers work outside an Islamic school in Eindhoven, November 8, 2004. A bomb ripped through the school that morning, causing serious damage to the entrance, but no injuries, police said. EPA/RoberT Vos/Landov Lions of Tawhid in the Polder Paul Aarts and Fadi Hirzalla The murder of the controversial filmmaker Theo van Gogh by a radical Islamist youth induced a deep national trauma in the Netherlands. Very quickly, debate about the murder and the subsequent outbreak of anti-Muslim violence led to a larger and disturbing debate about the place of Muslims and Islam in the traditionally tolerant country—and the meaning of tolerance itself. he second of November 2004 delivered a rude shock to his chest with a knife. The letter was addressed to Ayaan to Dutch society—long viewed by itself and by others Hirsi Ali, a Somalian-born ex-Muslim and a member of the Tas the most liberal and tolerant in Europe. Early in the Dutch parliament who had collaborated with Van Gogh on morning on that day, a radical Islamist named Mohammed his latest film, Submission, which the two of them made to Bouyeri awaited the filmmaker and provocateur Theo van “draw attention to the oppression of women in Islam.” In the Gogh near his residence in Amsterdam. When he spotted film, a woman appears veiled but semi-nude, her body cov- Van Gogh on his bike heading to work, Bouyeri shot and ered with whiplash marks and Qur’anic verses. “You mince stabbed him multiple times before pinning a five-page letter no words about your hostility to Islam,” Bouyeri’s letter