Download Booklet

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Year's Music

This is a reproduction of a library book that was digitized by Google as part of an ongoing effort to preserve the information in books and make it universally accessible. https://books.google.com fti E Y LAKS MV5IC 1896 juu> S-q. SV- THE YEAR'S MUSIC. PIANOS FOR HIRE Cramer FOR HARVARD COLLEGE LIBRARY Pianos BY All THE BEQUEST OF EVERT JANSEN WENDELL (CLASS OF 1882) OF NEW YORK Makers. 1918 THIS^BQQKJS FOR USE 1 WITHIN THE LIBRARY ONLY 207 & 209, REGENT STREET, REST, E.C. A D VERTISEMENTS. A NOVEL PROGRAMME for a BALLAD CONCERT, OR A Complete Oratorio, Opera Recital, Opera and Operetta in Costume, and Ballad Concert Party. MADAME FANNY MOODY AND MR. CHARLES MANNERS, Prima Donna Soprano and Principal Bass of Royal Italian Opera, Covent Garden, London ; also of 5UI the principal ©ratorio, dJrtlustra, artii Sgmphoiu) Cxmctria of ©wat Jfvitain, Jtmmca anb Canaba, With their Full Party, comprising altogether Five Vocalists and Three Instrumentalists, Are now Booking Engagements for the Coming Season. Suggested Programme for Ballad and Opera (in Costume) Concert. Part I. could consist of Ballads, Scenas, Duets, Violin Solos, &c. Lasting for about an hour and a quarter. Part II. Opera or Operetta in Costume. To play an hour or an hour and a half. Suggested Programme for a Choral Society. Part I. A Small Oratorio work with Chorus. Part II. An Operetta in Costume; or the whole party can be engaged for a whole work (Oratorio or Opera), or Opera in Costume, or Recital. REPERTOIRE. Faust (Gounod), Philemon and Baucis {Gounod) (by arrangement with Sir Augustus Harris), Maritana (Wallace), Bohemian Girl (Balfe), and most of the usual Oratorios, &c. -

Université De Montréal Par Justin Bernard Faculté De Musique Thèse

Université de Montréal Notes de programme. Une histoire, des pratiques et de nouveaux usages numériques par Justin Bernard Faculté de musique Thèse présentée en vue de l’obtention du grade de doctorat en musique, option musicologie Avril 2019 © Justin Bernard, 2019 RÉSUMÉ Depuis leur émergence au milieu du XIXe siècle, les notes de programme, contenant des informations parfois détaillées sur les œuvres qui s’apprêtent à être jouées, n’ont eu de cesse de s’adresser au public de concerts. Les besoins sont multiples, voire même divergents : donner des outils de compréhension intelligibles aux novices, qui découvrent la musique de compositeurs du passé ou de compositeurs actuels, et en même temps susciter la curiosité d’auditeurs déjà initiés, qui approfondissent ainsi leurs connaissances et leur culture personnelle. Il en va des notes de programme comme d’autres outils de vulgarisation musicale, partagés entre la volonté de rendre la musique classique accessible à tous et le devoir de rigueur musicologique auquel les connaisseurs sont en droit de s’attendre. Dans cette thèse, nous allions la théorie à la pratique. Outre les résultats d’une enquête réalisée en octobre 2017 dans le cadre de trois concerts produits par l’Orchestre symphonique de Montréal (ci-après, OSM) et qui porte notamment sur l’appréciation des notes de programme, nous présentons une série de courtes vidéos de vulgarisation que nous avons préparée pour l’OSM, au cours de la saison 2015-2016. La réalisation de ces nouveaux outils numériques s’appuie sur l’analyse d’un vaste corpus de notes de programme dont nous avons dégagé les tendances et les cas plus particuliers. -

A Place for Music: John Nash, Regent Street and the Philharmonic Society of London Leanne Langley

A Place for Music: John Nash, Regent Street and the Philharmonic Society of London Leanne Langley On 6 February 1813 a bold and imaginative group of music professionals, thirty in number, established the Philharmonic Society of London. Many had competed directly against each other in the heady commercial environment of late eighteenth-century London – setting up orchestras, promoting concerts, performing and publishing music, selling instruments, teaching. Their avowed aim in the new century, radical enough, was to collaborate rather than compete, creating one select organization with an instrumental focus, self-governing and self- financed, that would put love of music above individual gain. Among their remarkable early rules were these: that low and high sectional positions be of equal rank in their orchestra and shared by rotation, that no Society member be paid for playing at the group’s concerts, that large musical works featuring a single soloist be forbidden at the concerts, and that the Soci- ety’s managers be democratically elected every year. Even the group’s chosen name stressed devotion to a harmonious body, coining an English usage – phil-harmonic – that would later mean simply ‘orchestra’ the world over. At the start it was agreed that the Society’s chief vehicle should be a single series of eight public instrumental concerts of the highest quality, mounted during the London season, February or March to June, each year. By cooperation among their fee-paying members, they hoped to achieve not only exciting performances but, crucially, artistic continuity and a steady momentum for fine music that had been impossible before, notably in the era of the high-profile Professional Concert of 1785-93 and rival Salomon-Haydn Concert of 1791-2, 1794 and Opera Concert of 1795. -

The Pedagogical Legacy of Johann Nepomuk Hummel

ABSTRACT Title of Document: THE PEDAGOGICAL LEGACY OF JOHANN NEPOMUK HUMMEL. Jarl Olaf Hulbert, Doctor of Philosophy, 2006 Directed By: Professor Shelley G. Davis School of Music, Division of Musicology & Ethnomusicology Johann Nepomuk Hummel (1778-1837), a student of Mozart and Haydn, and colleague of Beethoven, made a spectacular ascent from child-prodigy to pianist- superstar. A composer with considerable output, he garnered enormous recognition as piano virtuoso and teacher. Acclaimed for his dazzling, beautifully clean, and elegant legato playing, his superb pedagogical skills made him a much sought after and highly paid teacher. This dissertation examines Hummel’s eminent role as piano pedagogue reassessing his legacy. Furthering previous research (e.g. Karl Benyovszky, Marion Barnum, Joel Sachs) with newly consulted archival material, this study focuses on the impact of Hummel on his students. Part One deals with Hummel’s biography and his seminal piano treatise, Ausführliche theoretisch-practische Anweisung zum Piano- Forte-Spiel, vom ersten Elementar-Unterrichte an, bis zur vollkommensten Ausbildung, 1828 (published in German, English, French, and Italian). Part Two discusses Hummel, the pedagogue; the impact on his star-students, notably Adolph Henselt, Ferdinand Hiller, and Sigismond Thalberg; his influence on musicians such as Chopin and Mendelssohn; and the spreading of his method throughout Europe and the US. Part Three deals with the precipitous decline of Hummel’s reputation, particularly after severe attacks by Robert Schumann. His recent resurgence as a musician of note is exemplified in a case study of the changes in the appreciation of the Septet in D Minor, one of Hummel’s most celebrated compositions. -

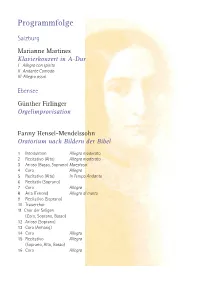

Programmfolge

Programmfolge Salzburg Marianne Martines Klavierkonzert in A-Dur I Allegro con spirito II Andante Comodo III Allegro assai Ebensee Günther Firlinger Orgelimprovisation Fanny Hensel-Mendelssohn Oratorium nach Bildern der Bibel 1 Intoduktion Allegro moderato 2 Recitativo (Alto) Allegro moderato 3 Arioso (Basso, Soprano) Maestoso 4 Coro Allegro 5 Recitativo (Alto) In Tempo Andante 6 Recitativ (Soprano) 7 Coro Allegro 8 Aria (Tenore) Allegro di molto 9 Recitativo (Soprano) 10 Trauerchor 11 Chor der Seligen (Coro, Soprano, Basso) 12 Arioso (Soprano) 13 Coro (Anhang) 14 Coro Allegro 15 Recitativo Allegro (Soprano, Alto, Basso) 16 Coro Allegro Programmnotizen Die Orgelimprovisation (Günther Firlinger) Das Konzert in Ebensee versteht sich als Portraitkonzert für die neu restaurierte und 1814: Der Kongress tanzt konzipierte Orgel der katholischen Pfarrkirche. (auf dem Vulkan) Die eingangs erklingende Improvisation stellt die Persönlichkeit des Instrumentes mit all ihren Klangmöglichkeiten und Farben in der Sprache des 20. Jahrhunderts vor. Der Akzent ist Beschäftigte sich die Gender Studies Reihe des Wintersemesters 13/14 mit Bertha v. Französisch, im Stile der großen Organisten-Komponisten Tradition eines Olivier Messiaen Suttner, die am Vorabend des Ersten Weltkrieges starb, so wird im Sommersemester 14 und oder Jean Langlais, zu dessen SchülerInnenkreis sich der Organist und Komponist Günther Wintersemester 14/15 das Jahr 1814 ins Zentrum gestellt. Firlinger zählt. Es ist die Zeit des Biedermeier, jene gar nicht so harmlose Zeit, die das Biedermeier selber Mitten im Oratorium wird sich dann die Hauptperson des Abends erneut zu Wort melden, noch gar nicht kannte. Das Ende der napoleonischen Kriege und der Wiener Kongress stehen diesmal in der Sprache des Bruders der Komponistin. -

George Polgreen Bridgetower (1779-1860)

George Polgreen Bridgetower (1779-1860) BLACK EUROPEANS: A British Library Online Gallery feature by guest curator Mike Phillips George Augustus Polgreen Bridgetower was probably born on 29 February 1780 (though some authorities give 11 October 1778) at Biała in Poland. His father, who went by the names John Frederick or Friedrich de August Bridgetower, worked in the household of Prince Esterházy, and gave several different stories about his background (the favourite being that he was an African prince. He was also “supposed by friends” to be the son of an Indian princess). The name Bridgetower favours the speculation that he was from Barbados (capital: Bridgetown). George’s mother was a Polish woman referred to as Maria or Mary Ann. Prince Esterházy’s family seat was actually in the castle Esterháza in Hungary (now Austria), which possessed an opera house and a puppet theatre, and boasted the composer Joseph Haydn as Kappelmeister. If Bridgetower was a child prodigy, destiny also provided him with the best possible environment and training. He made his performing début as a violinist, aged nine or 10, at the Concert Spirituel in Paris in April 1789. The journal Le Mercure de France raved about his performance, concluding that “his talent is one of the best replies one can give to philosophers who wish to deprive people of his nation and his colour of the opportunity to distinguish themselves in the arts”. After Paris, the Bridgetowers, father and son, turn up next in Windsor. According to Mrs Papendiek, Queen Charlotte’s assistant keeper of the wardrobe - “In 1789 An African Prince of the name Bridgetower, came to Windsor with a view of introducing his son, a most possessing lad of ten years old, and a fine violin player. -

UCL CMC Newsletter No.5

UCL Chamber Music Club Newsletter No.5 October 2015 In this issue: Welcome to our newsletter Welcome to the fifth issue of the Chamber Mu- Cohorts of muses, sic Club Newsletter and its third year of pub- unaccompanied lication. We offer a variety of articles, from a composers and large survey of last season’s CMC concerts – now a ensembles – a view on the regular feature – to some reflections, informed sixty-third season - by both personal experience and scholarship, page 2 on the music of Sibelius and Nielsen (whose 150th anniversaries are celebrated in the first UCLU Music Society concert of our new season). In the wake of UC- concerts this term - Opera’s production last March of J.C. Bach’s page 8 Amadis de Gaule we have a brief review and two articles outlining the composer’s biogra- UCOpera’s production of phy and putting him in a wider context. The Amadis de Gaule, CMC concert last February based on ‘the fig- UCL Bloomsbury Theatre, ure 8’ has prompted an article discussing some 23-28 March 2015 - aspects of the topic ‘music and numbers’. Not page 9 least, our ‘meet the committee’ series continues with an interview with one of our newest and Meet the committee – youngest committee members, Jamie Parkin- Jamie Parkinson - son. page 9 We hope you enjoy reading the newslet- A biographical sketch of ter. We also hope that more of our readers Johann Christian Bach will become our writers! Our sixth issue is (1735-82): composer, scheduled for February 2016, and any material impresario, keyboard on musical matters – full-length articles (max- player and freemason - imum 3000 words), book or concert reviews – page 12 will be welcome. -

Diplomats As Musical Agents in the Age of Haydn

HAYDN: The Online Journal of the Haydn Society of North America Volume 5 Number 2 Fall 2015 Article 2 November 2015 Diplomats as Musical Agents in the Age of Haydn Mark Ferraguto Follow this and additional works at: https://remix.berklee.edu/haydn-journal Recommended Citation Ferraguto, Mark (2015) "Diplomats as Musical Agents in the Age of Haydn," HAYDN: The Online Journal of the Haydn Society of North America: Vol. 5 : No. 2 , Article 2. Available at: https://remix.berklee.edu/haydn-journal/vol5/iss2/2 This Work in Progress is brought to you for free and open access by Research Media and Information Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in HAYDN: The Online Journal of the Haydn Society of North America by an authorized editor of Research Media and Information Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 1 Ferraguto, Mark "Diplomats as Musical Agents in the Age of Haydn." HAYDN: Online Journal of the Haydn Society of North America 5.2 (Fall 2015), http://haydnjournal.org. © RIT Press and Haydn Society of North America, 2015. Duplication without the express permission of the author, RIT Press, and/or the Haydn Society of North America is prohibited. Diplomats as Musical Agents in the Age of Haydn by Mark Ferraguto Abstract Vienna’s embassies were major centers of musical activity throughout the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. Resident diplomats, in addition to being patrons and performers, often acted as musical agents, facilitating musical interactions within and between courts, among individuals and firms, and in their private salons. Through these varied activities, they played a vital role in shaping a transnational European musical culture. -

MUSIC in the EIGHTEENTH CENTURY Western Music in Context: a Norton History Walter Frisch Series Editor

MUSIC IN THE EIGHTEENTH CENTURY Western Music in Context: A Norton History Walter Frisch series editor Music in the Medieval West, by Margot Fassler Music in the Renaissance, by Richard Freedman Music in the Baroque, by Wendy Heller Music in the Eighteenth Century, by John Rice Music in the Nineteenth Century, by Walter Frisch Music in the Twentieth and Twenty-First Centuries, by Joseph Auner MUSIC IN THE EIGHTEENTH CENTURY John Rice n W. W. NORTON AND COMPANY NEW YORK ē LONDON W. W. Norton & Company has been independent since its founding in 1923, when William Warder Norton and Mary D. Herter Norton first published lectures delivered at the People’s Institute, the adult education division of New York City’s Cooper Union. The firm soon expanded its program beyond the Institute, publishing books by celebrated academics from America and abroad. By midcentury, the two major pillars of Norton’s publishing program— trade books and college texts—were firmly established. In the 1950s, the Norton family transferred control of the company to its employees, and today—with a staff of four hundred and a comparable number of trade, college, and professional titles published each year—W. W. Norton & Company stands as the largest and oldest publishing house owned wholly by its employees. Copyright © 2013 by W. W. Norton & Company, Inc. All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America Editor: Maribeth Payne Associate Editor: Justin Hoffman Assistant Editor: Ariella Foss Developmental Editor: Harry Haskell Manuscript Editor: JoAnn Simony Project Editor: Jack Borrebach Electronic Media Editor: Steve Hoge Marketing Manager, Music: Amy Parkin Production Manager: Ashley Horna Photo Editor: Stephanie Romeo Permissions Manager: Megan Jackson Text Design: Jillian Burr Composition: CM Preparé Manufacturing: Quad/Graphics—Fairfield, PA Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Rice, John A. -

Haydn’S Creation and Enlightenment Theology

Haydn’s Creation and Enlightenment Theology MARK BERRY AYDN’S TWO GREAT ORATORIOS, The Creation and The Seasons (Die Schöpfung and Die Jahreszeiten) stand as monuments—on either side of the year 1800—to the Enlightenment and to the Austrian Enlightenment in particular. This is not to claim H “ ”— that they have no connection with what would often be considered more progressive broadly speaking, romantic—tendencies. However, like Haydn himself, they are works that, if a choice must be made, one would place firmly in the eighteenth century, “long” or otherwise. The age of musical classicism was far from dead by 1800, likewise the “Age of Enlightenment.” It is quite true that one witnesses in both the emergence of distinct national, even “nationalist,” tendencies.1 Yet these intimately connected “ages” remain essentially cosmopolitan, especially in the sphere of intellectual history and “high” culture. Haydn’s oratorios not only draw on Austrian tradition; equally important, they are also shaped by broader influence, especially the earlier English Enlightenment, in which the texts of both works have their origins. The following essay considers the theology of The Creation with reference to this background and, to a certain extent, also attempts the reverse, namely, to consider the Austrian Enlightenment in the light of a work more central to its concerns than might have been expected. Composers have always been subject to intellectual influences from without the strictly musical realm, even if this is not an object of inquiry to which great attention has always been devoted. The most cursory comparison of, say, texts set by Bach and those by Haydn would note a difference in intellectual milieu. -

The Bach Family There Has Never Been a Dynasty Like It! We Have

The Bach Family There has never been a dynasty like it! We have Johann Sebastian Bach to thank for much of the Genealogy as well. In the region of Thuringia, the name of Bach was synonymous with music, but they were also a 'family' experiencing the ups and downs of 17th & 18th century life, from happy marriages and joyful family music-making in this devoutly Lutheran community to coping with infant mortality and dysfunctional behaviour. The Bach Family encountered the lot. In this page, we visit the lives of key members of this remarkable family, a family that was humble in its intent, served the community, were appropriately deferential to their various patrons or princes, and whose music lives on through our performances today. Joh. Seb. Bach's ancestors set the tone and musical direction, but this particular family member raised the bar higher in scale and invention. Sebastian taught his own sons too, plus many of the offspring of his relatives. His eldest sons Wilhelm Friedemann and Carl Philipp Emanuel certainly held their Father in high regard, but also wanted to plough their own furrow - not easy even then. Others either held church or court positions and one travelled first to Italy and then to Georgian London in order to ply his trade - Johann Christian Bach, the youngest son. The family's ancestry goes back to the late 16th/early 17th centuries to a certain Vitus (Veit) Bach (d.1619) who left his native Hungary and came to live in Wechmar, near Gotha in Thuringia. He was a baker by trade. -

Playing with Art: Musical Arrangements As Educational Tools in Van Swieten’S Vienna

Playing with Art: Musical Arrangements as Educational Tools in van Swieten’s Vienna WIEBKE THORMÄHLEN We have the honour of announcing that the Creation, which was re- cently issued in score, may now be had not only in quintets for 2 vio- lins, 2 violas and violoncello arranged by Hrn. Anton Wranizky, but also for the klavier or fortepiano with all vocal parts arranged by Hrn. Sigmund Neukomm with every precision, energy and great fidelity to the beauties and originality of the full score. 342 Wiener Zeitung In March 1800, the Viennese publisher Artaria is- sued this announcement in the Wiener Zeitung, offering Joseph Haydn’s Creation arranged for string quintet. It is clear in a letter Haydn sent to Georg August Griesinger in October 1801 that the composer ap- proved of this arrangement: he applauded Anton Wranitzky’s skill in producing it and suggested that he should be invited to arrange The Seasons as well.1 What is more, Haydn’s letter shows that the question The epigraph is from the Wiener Zeitung, 24 (1800); quoted and trans. in H. C. Robbins Landon, Haydn: Chronicle and Works: The Years of “The Creation,” 1796–1800 (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1977), 542. 1 “As far as the arrangement of the Seasons for quartet or quintet is concerned, I think that Herr Wranizky, (Kapellmeister) at Prince Lobkowitz, should receive the pref- erence, not only because of his fine arrangement of the Creation, but also because I am The Journal of Musicology, Vol. 27, Issue 3, pp. 342–376, ISSN 0277-9269, electronic ISSN 1533-8347.