Diplomats As Musical Agents in the Age of Haydn

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Rise of the Tenor Voice in the Late Eighteenth Century: Mozart’S Opera and Concert Arias Joshua M

University of Connecticut OpenCommons@UConn Doctoral Dissertations University of Connecticut Graduate School 10-3-2014 The Rise of the Tenor Voice in the Late Eighteenth Century: Mozart’s Opera and Concert Arias Joshua M. May University of Connecticut - Storrs, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://opencommons.uconn.edu/dissertations Recommended Citation May, Joshua M., "The Rise of the Tenor Voice in the Late Eighteenth Century: Mozart’s Opera and Concert Arias" (2014). Doctoral Dissertations. 580. https://opencommons.uconn.edu/dissertations/580 ABSTRACT The Rise of the Tenor Voice in the Late Eighteenth Century: Mozart’s Opera and Concert Arias Joshua Michael May University of Connecticut, 2014 W. A. Mozart’s opera and concert arias for tenor are among the first music written specifically for this voice type as it is understood today, and they form an essential pillar of the pedagogy and repertoire for the modern tenor voice. Yet while the opera arias have received a great deal of attention from scholars of the vocal literature, the concert arias have been comparatively overlooked; they are neglected also in relation to their counterparts for soprano, about which a great deal has been written. There has been some pedagogical discussion of the tenor concert arias in relation to the correction of vocal faults, but otherwise they have received little scrutiny. This is surprising, not least because in most cases Mozart’s concert arias were composed for singers with whom he also worked in the opera house, and Mozart always paid close attention to the particular capabilities of the musicians for whom he wrote: these arias offer us unusually intimate insights into how a first-rank composer explored and shaped the potential of the newly-emerging voice type of the modern tenor voice. -

A Passion for Opera the DUCHESS and the GEORGIAN STAGE

A Passion for Opera THE DUCHESS AND THE GEORGIAN STAGE A Passion for Opera THE DUCHESS AND THE GEORGIAN STAGE PAUL BOUCHER JEANICE BROOKS KATRINA FAULDS CATHERINE GARRY WIEBKE THORMÄHLEN Published to accompany the exhibition A Passion for Opera: The Duchess and the Georgian Stage Boughton House, 6 July – 30 September 2019 http://www.boughtonhouse.co.uk https://sound-heritage.soton.ac.uk/projects/passion-for-opera First published 2019 by The Buccleuch Living Heritage Trust The right of Paul Boucher, Jeanice Brooks, Katrina Faulds, Catherine Garry, and Wiebke Thormählen to be identified as the authors of the editorial material and as the authors for their individual chapters, has been asserted in accordance with sections 77 and 78 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the authors. ISBN: 978-1-5272-4170-1 Designed by pmgd Printed by Martinshouse Design & Marketing Ltd Cover: Thomas Gainsborough (1727-1788), Lady Elizabeth Montagu, Duchess of Buccleuch, 1767. Portrait commemorating the marriage of Elizabeth Montagu, daughter of George, Duke of Montagu, to Henry, 3rd Duke of Buccleuch. (Cat.10). © Buccleuch Collection. Backdrop: Augustus Pugin (1769-1832) and Thomas Rowlandson (1757-1827), ‘Opera House (1800)’, in Rudolph Ackermann, Microcosm of London (London: Ackermann, [1808-1810]). © The British Library Board, C.194.b.305-307. Inside cover: William Capon (1757-1827), The first Opera House (King’s Theatre) in the Haymarket, 1789. -

The Anacreontic Society, the Antient

L_.0 un NUI MAYNOOTH 0 11 s c o i 1 na hÉireann Mé Nuad The music of three Dublin musical societies of the late eighteenth and nineteenth centuries: The Anacreontic Society, The Antient Concerts Society and The Sons of Handel. A descriptive catalogue. Catherine Mary Pia Kiely-Ferris Volume IV of IV: The Antient Concerts Society Bound Sets Catalogue and Appendices Thesis submitted to National University of Ireland, Maynooth for the Degree of Master of Literature in Music. Head of Department: Professor Gerard Gillen Music Department National University of Ireland, Maynooth Maynooth Co. Kildare Supervisor: Dr Barra Boydell Music Department National University of Ireland, Maynooth Maynooth Co. Kildare July 2005 TABLE OF CONTENTS Volume IV of IV 1: Cataloguing procedures and user guide............................................. 1 2: The Antient Concerts Society Bound Sets Catalogue....................12 3: Appendix A: The Anacreontic Society: composers and repertoire........................................................................................ 274 4: Appendix B: The Anacreontic Society: order of works within Bound Sets...................................................................................... 282 5: Appendix C: The Antient Concerts Society: composers and repertoire........................................................................................ 290 6: Appendix D: The Antient Concerts Society: order of works within Bound Sets..................................................................................... -

Rhetorical Concepts and Mozart: Elements of Classical Oratory in His Drammi Per Musica

Rhetorical Concepts and Mozart: elements of Classical Oratory in his drammi per musica A thesis submitted to the University of Newcastle in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Philosophy Heath A. W. Landers, BMus (Hons) School of Creative Arts The University of Newcastle May 2015 The thesis contains no material which has been accepted for the award of any other degree or diploma in any university or other tertiary institution and, to the best of my knowledge and belief, contains no material previously published or written by another person, except where due reference has been made in the text. I give consent to the final version of my thesis being made available worldwide when deposited in the University’s Digital Repository, subject to the provisions of the Copyright Act 1968. Candidate signature: Date: 06/05/2015 In Memory of My Father, Wayne Clive Landers (1944-2013) Requiem aeternam dona ei, Domine: et lux perpetua luceat ei. Acknowledgments Foremost, my sincerest thanks go to Associate Professor Rosalind Halton of the University Of Newcastle Conservatorium Of Music for her support and encouragement of my postgraduate studies over the past four years. I especially thank her for her support of my research, for her advice, for answering my numerous questions and resolving problems that I encountered along the way. I would also like to thank my co-supervisor Conjoint Professor Michael Ewans of the University of Newcastle for his input into the development of this thesis and his abundant knowledge of the subject matter. My most sincere and grateful thanks go to Matthew Hopcroft for his tireless work in preparing the musical examples and finalising the layout of this dissertation. -

Haydn's the Creation

Program Notes In the fall of 1790, a man appeared at Haydn’s rooms in Vienna with the abrupt introduction, “I am Salomon of London and have come to fetch you. Tomorrow we will arrange an accord.” Johann Peter Salomon’s meeting with the 58-year old Haydn was a turning point in Haydn’s long career. Under the impresario’s canny direction, Haydn’s two extended visits to London were not only extremely lucrative, but also musically invigorating, and he wrote some of his greatest works including his last twelve symphonies and his last six concert masses after 1791. And his sojourn in London directly led to what is perhaps his most popular work, the extraordinary and daringly original oratorio The Creation. Salomon’s proposal came at a particularly appropri- ate time for Haydn. Haydn was arguably the most renowned composer in Europe, despite having spent the last 30 years in the service of the House of Es- terházy. Prince Nikolaus entertained lavishly and took every opportunity to showcase his increasingly famous Kapellmeister, arranging elaborate musical evenings and even building an amphitheater where Haydn could present operas. The prince gave Haydn the opportunity to accept outside commissions and to publish, and there arose such an insatiable de- mand for Haydn’s music that pirated editions flourished and unscrupulous publishers actually affixed Haydn’s name to music written by his brother Michael, his pupils, and even random composers. But Prince Nikolaus sud- denly died in 1790, and his successor Prince Anton disbanded most of the Esterházy musical establishment. Haydn retained his nominal position as Kapellmeister, but had no official duties and was no longer required to be in residence. -

What Handel Taught the Viennese About the Trombone

291 What Handel Taught the Viennese about the Trombone David M. Guion Vienna became the musical capital of the world in the late eighteenth century, largely because its composers so successfully adapted and blended the best of the various national styles: German, Italian, French, and, yes, English. Handel’s oratorios were well known to the Viennese and very influential.1 His influence extended even to the way most of the greatest of them wrote trombone parts. It is well known that Viennese composers used the trombone extensively at a time when it was little used elsewhere in the world. While Fux, Caldara, and their contemporaries were using the trombone not only routinely to double the chorus in their liturgical music and sacred dramas, but also frequently as a solo instrument, composers elsewhere used it sparingly if at all. The trombone was virtually unknown in France. It had disappeared from German courts and was no longer automatically used by composers working in German towns. J.S. Bach used the trombone in only fifteen of his more than 200 extant cantatas. Trombonists were on the payroll of San Petronio in Bologna as late as 1729, apparently longer than in most major Italian churches, and in the town band (Concerto Palatino) until 1779. But they were available in England only between about 1738 and 1741. Handel called for them in Saul and Israel in Egypt. It is my contention that the influence of these two oratorios on Gluck and Haydn changed the way Viennese composers wrote trombone parts. Fux, Caldara, and the generations that followed used trombones only in church music and oratorios. -

Mozart's Piano

MOZART’S PIANO Program Notes by Charlotte Nediger J.C. BACH SYMPHONY IN G MINOR, OP. 6, NO. 6 Of Johann Sebastian Bach’s many children, four enjoyed substantial careers as musicians: Carl Philipp Emanuel and Wilhelm Friedemann, born in Weimar to Maria Barbara; and Johann Christoph Friedrich and Johann Christian, born some twenty years later in Leipzig to Anna Magdalena. The youngest son, Johann Christian, is often called “the London Bach.” He was by far the most travelled member of the Bach family. After his father’s death in 1750, the fifteen-year-old went to Berlin to live and study with his brother Emanuel. A fascination with Italian opera led him to Italy four years later. He held posts in various centres in Italy (even converting to Catholicism) before settling in London in 1762. There he enjoyed considerable success as an opera composer, but left a greater mark by organizing an enormously successful concert series with his compatriot Carl Friedrich Abel. Much of the music at these concerts, which included cantatas, symphonies, sonatas, and concertos, was written by Bach and Abel themselves. Johann Christian is regarded today as one of the chief masters of the galant style, writing music that is elegant and vivacious, but the rather dark and dramatic Symphony in G Minor, op. 6, no. 6 reveals a more passionate aspect of his work. J.C. Bach is often cited as the single most important external influence on Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart. Mozart synthesized the wide range of music he encountered as a child, but the one influence that stands out is that of J.C. -

Beethoven to Drake Featuring Daniel Bernard Roumain, Composer & Violinist

125 YEARS Beethoven to Drake Featuring Daniel Bernard Roumain, composer & violinist TEACHER RESOURCE GUIDE 87TH Annual Young People’s Concert William Boughton, Music Director Thank you for taking the NHSO’s musical journey: Beethoven to Drake Dear teachers, Many of us were so lucky to have such dedicated and passionate music teachers growing up that we decided to “take the plunge” ourselves and go into the field. In a time when we must prove how essential the arts are to a child’s growth, the NHSO is committed to supporting the dedication, passion, and excitement that you give to your students on a daily basis. We look forward to traveling down these roads this season with you and your students, and are excited to present the amazing Daniel Bernard Roumain. As a gifted composer and performer who crosses multiple musical genres, DBR inspires audience members with his unique take on Hip Hop, traditional Haitian music, and Classical music. This concert will take you and your students through the history of music - from the masters of several centuries ago up through today’s popular artists. This resource guide is meant to be a starting point for creation of your own lesson plans that you can tailor directly to the needs of your individual classrooms. The information included in each unit is organized in list form to quickly enable you to pick and choose facts and activities that will benefit your students. Each activity supports one or more of the Core Arts standards and each of the writing activities support at least one of the CCSS E/LA anchor standards for writing. -

The Compositional Influence of Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart on Ludwig Van Beethoven’S Early Period Works

Portland State University PDXScholar Young Historians Conference Young Historians Conference 2018 Apr 18th, 12:30 PM - 1:45 PM The Compositional Influence of olfW gang Amadeus Mozart on Ludwig van Beethoven’s Early Period Works Mary L. Krebs Clackamas High School Follow this and additional works at: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/younghistorians Part of the Musicology Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Krebs, Mary L., "The Compositional Influence of olfW gang Amadeus Mozart on Ludwig van Beethoven’s Early Period Works" (2018). Young Historians Conference. 7. https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/younghistorians/2018/oralpres/7 This Event is brought to you for free and open access. It has been accepted for inclusion in Young Historians Conference by an authorized administrator of PDXScholar. Please contact us if we can make this document more accessible: [email protected]. THE COMPOSITIONAL INFLUENCE OF WOLFGANG AMADEUS MOZART ON LUDWIG VAN BEETHOVEN’S EARLY PERIOD WORKS Mary Krebs Honors Western Civilization Humanities March 19, 2018 1 Imagine having the opportunity to spend a couple years with your favorite celebrity, only to meet them once and then receiving a phone call from a relative saying your mother was about to die. You would be devastated, being prevented from spending time with your idol because you needed to go care for your sick and dying mother; it would feel as if both your dream and your reality were shattered. This is the exact situation the pianist Ludwig van Beethoven found himself in when he traveled to Vienna in hopes of receiving lessons from his role model, Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart. -

Vivaldi's Four Seasons

Vivaldi's Four Seasons Paul Dyer AO Artistic Director 2019 Australian Brandenburg Orchestra SYDNEY PROGRAM City Recital Hall Telemann Concerto for 4 Violins in G major, TWV 40:201 Friday 1 November 7:00PM Directed by Matthew Bruce, Baroque violin Saturday 2 November 2:00PM Telemann Ouverture-Suite in C major, Water Music, TWV 55:C3 (Matinee) Directed by Ben Dollman, Baroque violin Saturday 2 November 7:00PM i Ouverture Wednesday 6 November 7:00PM ii Sarabande. Die schlafende Thetis (The sleeping Thetis) Wednesday 13 November 7:00PM iii Bourée. Die erwachende Thetis (Thetis awakening) Friday 15 November 7:00PM iv Loure. Der verliebte Neptunus (Neptune in love) Parramatta (Riverside Theatres) v Gavotte. Die spielenden Najaden (Playing Naiads) Monday 4 November 7:00pm vi Harlequinade. Der scherzenden Tritonen (The joking Triton) vii Der stürmende Aeolus (The stormy Aeolus) MELBOURNE viii Menuet. Der angenehme Zephir (The pleasant Zephir) Melbourne Recital Centre ix Gigue. Ebbe und Fluth (Ebb and Flow) Saturday 9 November 7:00PM x Canarie. Die lustigen Bots Leute (The merry Boat People) Sunday 10 November 5:00PM Interval Vivaldi Le Quattro Stagioni (The Four Seasons), Op. 8 No. 1-4 Solo Baroque violin, Shaun Lee-Chen Concerto No. 1 La primavera (Spring), RV 269 i Allegro ii Largo iii Allegro Concerto No. 2 L’estate (Summer), RV 315 i Allegro non molto–Allegro ii Adagio–Presto–Adagio iii Presto Concerto No. 3 L’autunno (Autumn), RV 293 i Allegro ii Adagio molto iii Allegro Concerto No. 4 L’inverno (Winter), RV 297 i Allegro non molto ii Largo iii Allegro CHAIRMAN’S 11 Proudly supporting our guest artists. -

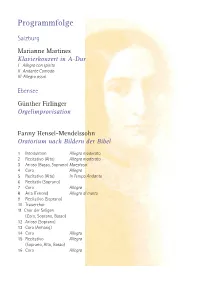

Programmfolge

Programmfolge Salzburg Marianne Martines Klavierkonzert in A-Dur I Allegro con spirito II Andante Comodo III Allegro assai Ebensee Günther Firlinger Orgelimprovisation Fanny Hensel-Mendelssohn Oratorium nach Bildern der Bibel 1 Intoduktion Allegro moderato 2 Recitativo (Alto) Allegro moderato 3 Arioso (Basso, Soprano) Maestoso 4 Coro Allegro 5 Recitativo (Alto) In Tempo Andante 6 Recitativ (Soprano) 7 Coro Allegro 8 Aria (Tenore) Allegro di molto 9 Recitativo (Soprano) 10 Trauerchor 11 Chor der Seligen (Coro, Soprano, Basso) 12 Arioso (Soprano) 13 Coro (Anhang) 14 Coro Allegro 15 Recitativo Allegro (Soprano, Alto, Basso) 16 Coro Allegro Programmnotizen Die Orgelimprovisation (Günther Firlinger) Das Konzert in Ebensee versteht sich als Portraitkonzert für die neu restaurierte und 1814: Der Kongress tanzt konzipierte Orgel der katholischen Pfarrkirche. (auf dem Vulkan) Die eingangs erklingende Improvisation stellt die Persönlichkeit des Instrumentes mit all ihren Klangmöglichkeiten und Farben in der Sprache des 20. Jahrhunderts vor. Der Akzent ist Beschäftigte sich die Gender Studies Reihe des Wintersemesters 13/14 mit Bertha v. Französisch, im Stile der großen Organisten-Komponisten Tradition eines Olivier Messiaen Suttner, die am Vorabend des Ersten Weltkrieges starb, so wird im Sommersemester 14 und oder Jean Langlais, zu dessen SchülerInnenkreis sich der Organist und Komponist Günther Wintersemester 14/15 das Jahr 1814 ins Zentrum gestellt. Firlinger zählt. Es ist die Zeit des Biedermeier, jene gar nicht so harmlose Zeit, die das Biedermeier selber Mitten im Oratorium wird sich dann die Hauptperson des Abends erneut zu Wort melden, noch gar nicht kannte. Das Ende der napoleonischen Kriege und der Wiener Kongress stehen diesmal in der Sprache des Bruders der Komponistin. -

Unwrap the Music Concerts with Commentary

UNWRAP THE MUSIC CONCERTS WITH COMMENTARY UNWRAP VIVALDI’S FOUR SEASONS – SUMMER AND WINTER Eugenie Middleton and Peter Thomas UNWRAP THE MUSIC VIVALDI’S FOUR SEASONS SUMMER AND WINTER INTRODUCTION & INDEX This unit aims to provide teachers with an easily usable interactive resource which supports the APO Film “Unwrap the Music: Vivaldi’s Four Seasons – Summer and Winter”. There are a range of activities which will see students gain understanding of the music of Vivaldi, orchestral music and how music is composed. It provides activities suitable for primary, intermediate and secondary school-aged students. BACKGROUND INFORMATION CREATIVE TASKS 2. Vivaldi – The Composer 40. Art Tasks 3. The Baroque Era 45. Creating Music and Movement Inspired by the Sonnets 5. Sonnets – Music Inspired by Words 47. 'Cuckoo' from Summer Xylophone Arrangement 48. 'Largo' from Winter Xylophone Arrangement ACTIVITIES 10. Vivaldi Listening Guide ASSESSMENTS 21. Transcript of Film 50. Level One Musical Knowledge Recall Assessment 25. Baroque Concerto 57. Level Two Musical Knowledge Motif Task 28. Programme Music 59. Level Three Musical Knowledge Class Research Task 31. Basso Continuo 64. Level Three Musical Knowledge Class Research Task – 32. Improvisation Examples of Student Answers 33. Contrasts 69. Level Three Musical Knowledge Analysis Task 34. Circle of Fifths 71. Level Three Context Questions 35. Ritornello Form 36. Relationship of Rhythm 37. Wordfind 38. Terminology Task 1 ANTONIO VIVALDI The Composer Antonio Vivaldi was born and lived in Italy a musical education and the most talented stayed from 1678 – 1741. and became members of the institution’s renowned He was a Baroque composer and violinist.