The Rural Sustainable Development Through Renewable Energy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Romania National Report

Wide the SEE by Succ Mod Romania National Report Harghita Energy Management Public Service & UEM-CARDT The sole responsibility for the content of this publication lies with the authors. It does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the European Communities. The European Commission is not responsible for any use that may be made of the information contained therein. Romania National Report UEM-CARDT pag 1 Table of content A) INTRODUCTION 1. General overview of the country: 1.1. Meteorology: temperatures, global daily radiation 1.2. Anaglyph / Relief (use of territory) 1.3. Population: evolution for the last 1 year, actual situation and forecast 1.4. Macroeconomic statistics (GDP, per capita GDP, Per main sector GDP percentage, Sectors of activity, Employment – Unemployment, Indicators) 1.5. Statistical data for energy consumption, dependency on energy imports, price evolution, forecast for energy consumption, CO2 emissions (Kyoto Protocol commitments), etc B) STATE OF THE MARKET 2. Overview of the national market situation 2.1. Solar collector production and sales 2.2. Estimated solar parks in present year 2.3. Estimated annual solar thermal energy production in present year, equivalent CO2 emissions avoided in current year (on the basis of oil) 2.4. Product types and solar thermal applications 2.5. Market share of major manufacturers (per product type and application) 2.6. Sector employment 2.7. Imports - Exports C) STATE OF PRODUCTION 3. Main characteristics of production firms (size, concentration, mentality, financial capacity etc.) 4. Product technology and production methods 4.1. Product technology description of typical solar domestic hot water systems 5. Breakdown of solar systems’ cost 5.1. -

Harnessing Eu Funds for Romania's Renewable

HARNESSING EU FUNDS FOR ROMANIA’S RENEWABLE ENERGY TRANSITION Published in March 2021 by Sandbag. This report is published under a Creative Commons licence. You are free to share and adapt the report, but you must credit the authors and title, and you must share any material you create under the same licence. Principal Authors Manuel Herlo Ciara Barry Thanks We are grateful to the European Climate Foundation for helping to fund this work. The report’s conclusions remain independent. With thanks to Adrien Assous, Eusebiu Stamate and Julie Ducasse for helpful comments and input on this report, and to Laura Nazare, Raphael Hanoteaux, Martin Moise, Thomas Garabetian, Alberto Rocamora and Robert Gavriliuc for their feedback and advice. Image credits Front cover image by Karsten Würth on Unsplash. Report design Ciara Barry Copyright © Sandbag, 2021 Contents 1. Introduction 1 2. The Energy System in Romania 3 2.1 Developments in renewable energy 4 2.2 Growth in the gas sector 6 3. Funding opportunities for the Energy Transition 9 3.1 The EU budget and climate mainstreaming 9 3.2 The EU ETS as a revenue recycling scheme 12 4. Geothermal energy 16 4.1 Uses of geothermal energy 16 4.2 Assessing geothermal energy potential 17 4.3 Advantages and disadvantages of geothermal energy 18 4.4. Geothermal energy in Romania 21 5. Bioenergy 26 5.1 Sources of bioenergy 26 5.2 Evaluating bioenergy potential 28 5.3 Advantages and disadvantages of bioenergy 28 5.4 Bioenergy in Romania 30 6. Conclusion and policy recommendations 35 1. Introduction The European Union has set out a vision to become climate neutral by 2050, the first economy with net-zero greenhouse gas emissions. -

CODE of GOOD PRACTICE for RENEWABLE ENERGY in ROMANIA 2021 Dear Reader

CODE OF GOOD PRACTICE FOR RENEWABLE ENERGY IN ROMANIA 2021 Dear Reader, Carlo Pignoloni CEO, Enel Romania President of the Board, RWEA You may wonder why the Romanian Wind Energy Association (RWEA) decided to issue a Code of Good Practice for the industry now, in 2021, more than 10 years since the first wind energy projects in the country were commissioned. Wind energy, with more than 3000 MW installed, has become one of the major energy sources in the country and last year accounted for almost 14% of the total energy produced in Romania. While this is a very important share, adding to the sizeable quota of renewable energy generation in Romania, it is quite safe to say that we are far from the country’s potential. RWEA members demonstrated that they came to invest in the country for the long term, supported economic growth and technological advance and are part of the backbone of the energy sector. But there is much more left to be done. At the time when I am writing these lines, several new renewable projects have been announced in Romania by different companies, and the pipeline is expected to grow significantly. This is a welcome development, as Romania’s generation fleet is ageing and needs to be replaced quickly and at optimal costs. The country, its economy and its people need access to affordable, reliable, sustainable and modern energy and one cannot overemphasize wind’s importance. This brings me to the purpose of this Code and its timing. In order to make this transition just, we need to think of all stakeholders and improve the quality of life of citizens-customers. -

Changes in Renewable Energy Policy and Their Implications: the Case of Romanian Producers

energies Article Changes in Renewable Energy Policy and Their Implications: The Case of Romanian Producers Nicolae Marinescu MTSAI Department, Faculty of Economic Sciences and Business Administration, Transilvania University of Brasov, 500036 Brasov, Romania; [email protected] Received: 18 November 2020; Accepted: 6 December 2020; Published: 9 December 2020 Abstract: This paper analyzes the impact of policy changes on the Romanian renewable energy producers. Attracted by a generous subsidy scheme, foreign and domestic investors flocked to the market. Consequently, the sector witnessed remarkable progress, especially in the wind power category. Romania fast approached the national target set by the European Union concerning the share of the country’s energy consumption from renewable sources. However, frequent changes in the support scheme and in the regulations issued by public authorities led to chaos. The aim of the paper was to emphasize the evolution of renewable energy policy in Romania, to investigate the incentives and their effects, and to critically assess the impact of the changes on renewable energy producers. It highlights, by means of an exploratory study and several interviews with executives of renewable energy companies, the challenges and shortcomings of policymaking. The main finding was that the revision of the subsidy scheme and the changes in energy policy that followed are the major determinants for the declining financial performance of renewable energy producers. Subsequently, some recommendations for improved policymaking are suggested, so as to re-establish the trust of investors and to promote the sustainable development of the sector. Keywords: renewable energy; energy policy; energy market; subsidies; electricity; green certificates 1. Introduction The use of renewable energy has been encouraged and supported by the European Union (EU) to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, achieve energy policy goals of sustainability, security and increased efficiency, and to reduce its dependency on foreign energy suppliers. -

Romania Empowered Lives

RENEWABLE ENERGY SNAPSHOT: Romania Empowered lives. Resilient nations. General Country Electricity Generating Information Capacity 2012 Population: 21,326,905 Surface Area: 238,390 km² 22,000 MW 10.9% Capital City: Bucharest Total Installed Capacity RE Share GDP (2012): $ 169.4 billion GDP Per Capita (2012): $ 7,943 2,378 MW Installed RE Capacity WB Ease of Doing Business: 73 Biomass Solar PV Wind Small Hydro Installed Renewable Electricity Capacity 2012 in MW 16.8 6.4 1,905 450 Technical Potential for Installed 12,100 219,700 14,000 1,100 Renewable Electricity Capacity in MW Sources : EBRD(2009); WWEA (2013); EurObserv’Er (2013); KPMG (b) (2012); ESHA (2012); World Bank(2014); Armand Consulting (2010); Renewable Facts (2013); EIA (2013); Hoogwijk and Graus (2008); Hoogwijk (2004); JRC (2011); and UNDP calculations. Key information about renewable energy in Romania Romania’s share of renewable energy to total installed capacity has risen in recent years to 11 percent by the end of 2012. In 2012, it showed the highest global growth rate for commissioned wind power plants (including only markets bigger than 200 MW of installed capacity), and 1079 MW of wind power plants was installed in that year (WWEA, 2013). This was due to a support scheme of quota obligations, minimum and maximum prices and tradable renewable energy certificates introduced in 2008. In the quota system, electricity suppliers and producers are obliged to produce a fixed quantity of renewable energy per year (increasing annually from 14 percent in 2013 to 20 percent in 2020) (Law No. 220/2008, Art. 4 [4&5]). -

HOUSING in ROMANIA Project Co-Financed from the European Regional Development Fund Through the Operational Programme Technical Assistance (OPTA) 2007-2013

Public Disclosure Authorized HOUSING IN ROMANIA Project co-financed from the European Regional Development Fund through the Operational Programme Technical Assistance (OPTA) 2007-2013 Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized TOWARDS A NATIONAL HOUSING STRATEGY Public Disclosure Authorized Regional Development Program 2 | Harmonizing Public Investments Component 4: FINAL REPORT (1) August 27, 2015 i ii Contents Abbreviations and Acronyms .............................................................................................................................................. v Currency Equivalents ........................................................................................................................................................... vii Acknowledgements ............................................................................................................................................................. viii EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ......................................................................................................................................... 1 I. INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................................... 28 1.1 Background .................................................................................................................................................... 28 1.2 Definitions ...................................................................................................................................................... -

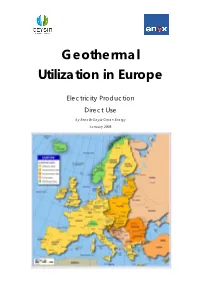

Geothermal Utilization in Europe

Geothermal Utilization in Europe Electricity Production Direct Use by Enex & Geysir Green Energy January 2008 Geysir Green Energy. Enex Table of Index 1 INTRODUCTION................................................................................................................. 2 2 HISTORY OF GEOTHERMAL UTILIZATION IN EUROPE ............................................... 2 3 GEOTHERMAL RESOURCES........................................................................................... 2 3.1 ELECTRICITY GENERATION............................................................................................... 3 3.2 DIRECT HEAT USES ......................................................................................................... 3 3.3 HOT DRY ROCK .............................................................................................................. 3 4 GEOTHERMAL UTILIZATION AND POTENTIAL IN EUROPE........................................ 3 4.1 HIGH TEMPERATURE GEOTHERMAL COUNTRIES ................................................................ 6 4.1.1 Iceland.................................................................................................................... 6 4.1.2 Italy......................................................................................................................... 7 4.1.3 Portugal - Azores ................................................................................................... 7 4.1.4 Turkey ................................................................................................................... -

US Department of State Self Study Guide for Moldova, March 2002

Description of document: US Department of State Self Study Guide for Moldova, March 2002 Requested date: 11-March-2007 Released date: 25-Mar-2010 Posted date: 19-April-2010 Source of document: Freedom of Information Act Office of Information Programs and Services A/GIS/IPS/RL U. S. Department of State Washington, D. C. 20522-8100 Fax: 202-261-8579 Note: This is one of a series of self-study guides for a country or area, prepared for the use of USAID staff assigned to temporary duty in those countries. The guides are designed to allow individuals to familiarize themselves with the country or area in which they will be posted. The governmentattic.org web site (“the site”) is noncommercial and free to the public. The site and materials made available on the site, such as this file, are for reference only. The governmentattic.org web site and its principals have made every effort to make this information as complete and as accurate as possible, however, there may be mistakes and omissions, both typographical and in content. The governmentattic.org web site and its principals shall have neither liability nor responsibility to any person or entity with respect to any loss or damage caused, or alleged to have been caused, directly or indirectly, by the information provided on the governmentattic.org web site or in this file. The public records published on the site were obtained from government agencies using proper legal channels. Each document is identified as to the source. Any concerns about the contents of the site should be directed to the agency originating the document in question. -

The European Green Deal

The European Green Deal Decarbonizing the Romanian energy sector though renewables April 2021 Contents Chapter Title Page Foreword 03 China vs. USA: a battle for decarbonization? 04 Europe’s path towards fighting climate change: The Green Deal 07 Romania’s energy market and the Green Deal 11 Low-carbon energy transition in Romania: private & public initiatives 14 What should Romania do in order to achieve Green Deal targets and 18 thrive in the renewables arena? Project team 20 About this report The support framework offered by the European Green Deal is a key driver for the transition to low emission energy industries across the European Union. The level of investments in the area of renewable energy in Romania will depend on appropriate regulations and governmental support and a perfect synchronization with current business intentions. The report analyzes current trends on the Romanian energy market, as well as other energy sector developments within large economies that reflect the importance of renewable energy adoption across the globe for a timely and appropriate response to climate change. Foreword Climate change has become a central topic on everyone’s agenda, private Nevertheless, climate change or public actors, illustrating the negationism, populism and low scientists’ concerns on the impact of adoption of renewables in some economic activities on the countries have undermined the environment. While many large efforts made so far in terms of companies across the globe have decarbonization and fighting climate expressed their commitment to a change. more sustainable world, COVID-19 has shown the vulnerabilities of the The decarbonization of Romania’s business environment. -

(Sub)Peripheries. Giordano, Christian

NICOLAUS COPERNICUS UNIVERSITY DEPARTMENT OF SOCIOLOGY 23’ 2017 Toruń 2017 ADVISORY COUNCIL Anna Bandler (Slovak Agricultural University), David Brown (Cornell University, USA), Krzysztof Gorlach (Jagiellonian University, Poland), Andrzej Kaleta (Nicolaus Copernicus University, Poland), Miguel Angel Sobrado (National University of Costa Rica), Irén Szörényiné Kukorelli (Hungarian Academy of Sciencies, Hungary), Michal Lošták (Czech University of life Sciences, Czech Republic), Feng Xingyuan (Chinese Academy of Social Sciences) EDITORIAL BOARD Christian Giordano – Member László J. Kulcsár – Member Monika Kwiecińska-Zdrenka – Managing Editor Lutz Laschewski – Member Iwona Leśniewicz – Editorial Assistant Elwira Piszczek – Deputy Editor Nigel Swain – Member Th e journal is published annually by Th e Nicolaus Ccopernicus University in Toruń, Poland Contact: 87–100 Toruń, Fosa Staromiejska 1a, Poland www.soc.uni.torun.pl/eec, [email protected] Eastern European Countryside from the beginning of May 2007 Index ®, Social Scisearch® and Journal citation Reports/Social Sciences Edition ThThe e issue issue 21’2015 23’2017 is isfi nancedco-financed by the Polishby the Ministry Ministry ofof ScienceScience andand Higher Higher Education Education – – grant785-P-DUN-2017 1144/P-DUN/2015 ENGLISH LANGUAGE EDITOR Th e electronic version is published at: © Copyright by Uniwersytet Mikołaja Kopernika ISSN 1232–8855 NICOLAUS COPERNICUS UNIVERSITY ul. Gagarina 11, 87–100 Toruń Print: Nicolaus Copernicus University Press Edition: 300 copies Contents Articles and studies Krystyna Szafraniec, Paweł Szymborski, Krzysztof Wasielewski Between the School and Labour Market. Rural Areas and Rural Youth in Poland, Romania and Russia....................................... 5 Tésits Róbert, Alpek Levente Social Innovations for the Disadvantaged Rural Regions: Hungarian Experiences of the New Type Social Cooperatives....................... 27 Yuliana Yarkova, Emil Mutafov Rural Areas in Bulgaria - Investigation on Some Factors for Development . -

21 Doi: 10.24818/18423264/53.3.19.02

Economic Computation and Economic Cybernetics Studies and Research, Issue 3/2019; Vol. 53 ________________________________________________________________________________ Professor Liviu Stelian BEGU, PhD Department of Statistics and Econometrics The Bucharest University of Economic Studies E-mail: [email protected] Associate Professor Ioana Teodora MESTER, PhD Lectures Ramona SIMUT, PhD Lectures Mariana SEHLEANU, PhD Lectures Diana PERTICAS, PhD Department of Economics and Business University of Oradea, Oradea ECONOMIC AND ENVIRONMENTAL IMPLICATIONS OF ENERGY TAXES: EVIDENCE FROM ROMANIA Abstract. This study investigates the relationship between the energy taxes from Romanian and several explanatory variables related to economic growth, carbon dioxide emissions, renewable and non-renewable energy in the country. After reviewing the main relevant aspects and contributions related to the relation between these variables, we launched and tested three hypotheses related to the possible causal relationship between energy taxes, gross domestic product (GDP), carbon dioxide emissions (CO2), renewable energy types and non-renewable energy by using the Johansen cointegration test and Granger causality. The Granger causality test yields evidence of a long-run Granger causality running from: GDP to energy taxes, CO2 to energy taxes, renewable energy types to energy taxes, respectively from energy taxes to CO2, renewable and non-renewable energy types. Regarding the evidence of a short-run unidirectional causal relationship between variables, there is one from CO2 and non-renewable to energy taxes, respectively from energy taxes to renewable energy types. Keywords: energy; tax; economic growth; renewable energy; carbon dioxide emission. JEL classification: C32, O4, Q2, Q4, Q3 1. Introduction In the context of ensuring sustainable development, the study of the influence of environmental taxes, both from an economic and environmental perspective, becomes crucial. -

R O M a N I A

R O M A N I A Regular Review of Energy Effi ciency Policies 2006 PEEREA Energy Charter Protocol on Energy Effi ciency and Related Environmental Aspects Aspects Environmental Related and ciency Effi Energy on Protocol Charter Energy Energy Charter Protocol on Energy Efficiency and Related Environmental Aspects PEEREA Romania REGULAR REVIEW 2006 Part I: Trends in energy and energy efficiency policies, instruments and actors TABLE OF CONTENTS 0. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY......................................................................... 1 1. INTRODUCTION ..................................................................................... 6 2. BACKGROUND: ENERGY POLICIES AND PRICES ............................ 8 2.1. Energy Policy - General Trends and Objectives .......................................................................8 2.2. Energy Policy Implementation..................................................................................................12 2.3. Energy Prices..............................................................................................................................14 3. END-USE SECTORS ............................................................................ 17 3.1. Residential Sector.......................................................................................................................19 3.2. Industrial Sector.........................................................................................................................22 3.3. Services Sector............................................................................................................................24