Hurricane Shoes and Other Stories

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

WANG (CHINA) (CHINA) ENTRY # NAME of DOG, PCCISB No

FRF 21st FRF ALL BREEDS CHAMPIONSHIP DOG SHOW November 11, 2018 SM SEASIDE MALL, CEBU CITY SHEEPDOGS AND CATTLE DOGS BORDER COLLIE ZHI WEI "AIDY" WANG (CHINA) (CHINA) ENTRY # NAME OF DOG, PCCISB No. AWARDS POINTS 1 NJYGQS THREE (CHN), PCCISB CKU-297438447/18 WD,BD,BOB,BIG-2 BJIB,BJIG 0 Owner : ZHAO QIANG KUN Breeder: LIU YUN LONG WELSH CORGI (PEMBROKE) ZHI WEI "AIDY" WANG (CHINA) (CHINA) ENTRY # NAME OF DOG, PCCISB No. AWARDS POINTS 2 NECTARLAND MACONDE (CHN), PCCISB CKU-39331966/17 WD,BD,BOB,BIG,BIS-2 5 Owner : ZHAO QIANG KUN Breeder: HUANG YU NING 3 PHIL GR CH BEST BRILLIANT VARY DAN'S (BEL), PCCISB 1482ZB3 RBD 0 Owner : JEFFREY G LIM Breeder: MAZANCHUK L M 4 PHIL GR CH ODESSA MAMMA ANAITIS (BEL), PCCISB 1334ZB3 BOS,BB 0 Owner : JEFFREY G LIM Breeder: KRAVTSOV YU PINSCHER AND SCHNAUZER - MOLOSSOID BREEDS BOXER ZHI WEI "AIDY" WANG (CHINA) (CHINA) ENTRY # NAME OF DOG, PCCISB No. AWARDS POINTS 5 X-CELLENCE MAN OF STEEL, PCCISB 12072F3 WD,BD,BOS BPIB,BPIS-2 1 Owner : DENNIS L TAN & BARBARA G TAN Breeder: DENNIS TAN & BARBARA TAN & AARON GO 7 PHIL CH X-CELLENCE LORD & TAYLOR, PCCISB 11847F3 RBD 0 Owner : DENNIS L TAN & BARBARA TAN Breeder: DENNIS L TAN & BARBARA TAN 10 X-CELLENCE GRAND MAJESTY, PCCISB 11972F3 WB,BB,BOB,BOW,BIG-3 BPB 5 Owner : DENNIS L TAN & BARBARA TAN Breeder: DENNIS L TAN & BARBARA TAN 14 KAMAKRIS'S DIVA OF X-CELLENCE (USA), PCCISB 11669F3 RWB 0 Owner : DENNIS & BARBARA TAN & KAMIRON ALYSSA BELCHEBreeder: MS KAMIRON ALYSSA BELCHER 15 PHIL GR CH X-CELLENCE LADY LUCK, PCCISB 11841F3 RBB 0 Owner : DENNIS L TAN & BARBARA TAN Breeder: DENNIS L TAN & BARBARA TAN BULLDOG ZHI WEI "AIDY" WANG (CHINA) (CHINA) ENTRY # NAME OF DOG, PCCISB No. -

This Book Was First Published in 1951 by Little, Brown and Company

This book was first published in 1951 by Little, Brown and Company. THE CATCHER IN THE RYE By J.D. Salinger © 1951 CHAPTER 1 If you really want to hear about it, the first thing you'll probably want to know is where I was born, an what my lousy childhood was like, and how my parents were occupied and all before they had me, and all that David Copperfield kind of crap, but I don't feel like going into it, if you want to know the truth. In the first place, that stuff bores me, and in the second place, my parents would have about two hemorrhages apiece if I told anything pretty personal about them. They're quite touchy about anything like that, especially my father. They're nice and all--I'm not saying that--but they're also touchy as hell. Besides, I'm not going to tell you my whole goddam autobiography or anything. I'll just tell you about this madman stuff that happened to me around last Christmas just before I got pretty run-down and had to come out here and take it easy. I mean that's all I told D.B. about, and he's my brother and all. He's in Hollywood. That isn't too far from this crumby place, and he comes over and visits me practically every week end. He's going to drive me home when I go home next month maybe. He just got a Jaguar. One of those little English jobs that can do around two hundred miles an hour. -

”Shoes”: a Componential Analysis of Meaning

Vol. 15 No.1 – April 2015 A Look at the World through a Word ”Shoes”: A Componential Analysis of Meaning Miftahush Shalihah [email protected]. English Language Studies, Sanata Dharma University Abstract Meanings are related to language functions. To comprehend how the meanings of a word are various, conducting componential analysis is necessary to do. A word can share similar features to their synonymous words. To reach the previous goal, componential analysis enables us to find out how words are used in their contexts and what features those words are made up. “Shoes” is a word which has many synonyms as this kind of outfit has developed in terms of its shape, which is obviously seen. From the observation done in this research, there are 26 kinds of shoes with 36 distinctive features. The types of shoes found are boots, brogues, cleats, clogs, espadrilles, flip-flops, galoshes, heels, kamiks, loafers, Mary Janes, moccasins, mules, oxfords, pumps, rollerblades, sandals, skates, slides, sling-backs, slippers, sneakers, swim fins, valenki, waders and wedge. The distinctive features of the word “shoes” are based on the heels, heels shape, gender, the types of the toes, the occasions to wear the footwear, the place to wear the footwear, the material, the accessories of the footwear, the model of the back of the shoes and the cut of the shoes. Keywords: shoes, meanings, features Introduction analyzed and described through its semantics components which help to define differential There are many different ways to deal lexical relations, grammatical and syntactic with the problem of meaning. It is because processes. -

Arthur Suydam: “Heroes Are What We Aspire to Be”

Ro yThomas’’ BXa-Ttrta ilor od usinary Comiics Fanziine DARK NIGHTS & STEEL $6.95 IN THE GOLDEN & SILVER AGES In the USA No. 59 June 2006 SUYDAM • ADAMS • MOLDOFF SIEGEL • PLASTINO PLUS: MANNING • MATERA & MORE!!! Batman TM & ©2006 DC Comics Vol. 3, No. 59 / June 2006 ™ Editor Roy Thomas Associate Editors Bill Schelly Jim Amash Design & Layout Christopher Day Consulting Editor John Morrow FCA Editor P.C. Hamerlinck Comic Crypt Editor Michael T. Gilbert Editors Emeritus Jerry Bails (founder) Contents Ronn Foss, Biljo White, Mike Friedrich Writer/Editorial: Dark Nights & Steel . 2 Production Assistant Arthur Suydam: “Heroes Are What We Aspire To Be” . 3 Eric Nolen-Weathington Interview with the artist of Cholly and Flytrap and Marvel Zombies covers, by Renee Witterstaetter. Cover Painting “Maybe I Was Just Loyal” . 14 Arthur Suydam 1950s/60s Batman artist Shelly Moldoff tells Shel Dorf about Bob Kane & other phenomena. And Special Thanks to: “My Attitude Was, They’re Not Bosses, They’re Editors” . 25 Neal Adams Richard Martines Golden/Silver Age Superman artist Al Plastino talks to Jim Kealy & Eddy Zeno about his long Heidi Amash Fran Matera and illustrious career. Michael Ambrose Sheldon Moldoff Bill Bailey Frank Motler Jerry Siegel’s European Comics! . 36 Tim Barnes Brian K. Morris When Superman’s co-creator fought for truth, justice, and the European way—by Alberto Becattini. Dennis Beaulieu Karl Nelson Alberto Becattini Jerry Ordway “If You Can’t Improve Something 200%, Then Go With The Thing John Benson Jake Oster That You Have” . 40 Dominic Bongo Joe Petrilak Modern legend Neal Adams on the late 1960s at DC Comics. -

Tracing Fairy Tales in Popular Culture Through the Depiction of Maternity in Three “Snow White” Variants

University of Louisville ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository College of Arts & Sciences Senior Honors Theses College of Arts & Sciences 5-2014 Reflective tales : tracing fairy tales in popular culture through the depiction of maternity in three “Snow White” variants. Alexandra O'Keefe University of Louisville Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.library.louisville.edu/honors Part of the Children's and Young Adult Literature Commons, and the Comparative Literature Commons Recommended Citation O'Keefe, Alexandra, "Reflective tales : tracing fairy tales in popular culture through the depiction of maternity in three “Snow White” variants." (2014). College of Arts & Sciences Senior Honors Theses. Paper 62. http://doi.org/10.18297/honors/62 This Senior Honors Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the College of Arts & Sciences at ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in College of Arts & Sciences Senior Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. This title appears here courtesy of the author, who has retained all other copyrights. For more information, please contact [email protected]. O’Keefe 1 Reflective Tales: Tracing Fairy Tales in Popular Culture through the Depiction of Maternity in Three “Snow White” Variants By Alexandra O’Keefe Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for Graduation summa cum laude University of Louisville March, 2014 O’Keefe 2 The ability to adapt to the culture they occupy as well as the two-dimensionality of literary fairy tales allows them to relate to readers on a more meaningful level. -

Saturday, May 9, 2020 @ 12 PM South East Mississippi Livestock 7677 US Hwy 49 • Hattiesburg, MS

Saturday, May 9, 2020 @ 12 PM South East Mississippi Livestock 7677 US Hwy 49 • Hattiesburg, MS INDEX OF CONSIGNORS FOR PUREBRED CATTLE Thursday, May 7, 2020 Preview Cattle CONSIGNOR . .LOTS Bogue Chitto Cattle Co., Tyler Kohen, MS 662.574.1176.............C-F Friday, May 8, 2020 Lee Cattle, Asa Lee, MS 610.916.6138 . G Preview Cattle All Day B & P Brahmans, Matt Pounds, AL 334.590.7535...................H Bogue Chitto Cattle Co., Tyler Kohen, MS 662.574.1176...............I Raymond Doreck, TX 409.392.8599..............................J Sale Day Schedule Ward Cattle, Tyson Ward, FL 863.287.7415 ....................... K Bogue Chitto Cattle Co., Tyler Kohen, MS 662.574.1176.............1-6 Saturday, May 9, 2020 Miskmon Ranch, Rick Miskmon, TX 214.546.5366................7-13 Ward Cattle, Tyson Ward, FL 863.287.7415 ....................14-19 Preview Cattle until 11:00 Pickett Farms, Michael Pickett, LA 318.663.1978 ...............20-23 Lee Cattle, Asa Lee, MS 610.916.6138 . 24 Lunch 11:00 provided by Bogue Chitto Cattle RS Cattle, Robbie Saucier, MS 228.731.4710...................25-26 Sale . 12:00 Big Hat Cattle, Walter Honea, TN 931.993.1077 ................... 27 Anderson Brahman, MS 601.270.1062 . .28-40 Wedgeworth Cattle, Lance Wedgeworth, MS 228.860.6088 ........41-45 Auctioneer Sidewinder Cattle, Ed Shehee, FL 850.572.6595 ................46-54 Philip Gilstrap B&P Brahmans, Matt Pounds, AL 334.590.7535...................55-59 Tyler Farms, Wes Tyler, AL 256-673-2672 .....................60-63 McCartney Farms, Tater McCartney, LA 318.316.3886............64-73 Sales Managers Ricky Hughes, AR 501.844.5624 ............................74-78 L & MC Farms, Leo Calligaro 321.277.2055....................79-85 Philip Gilstrap . -

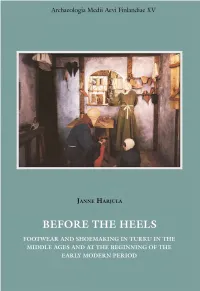

Footwear and Shoemaking in Turku in the Middle Ages and at the Beginning of the Early Modern Period

Janne Harjula Before the Heels Footwear and Shoemaking in Turku in the Middle Ages and at the Beginning of the Early Modern Period Archaeologia Medii Aevi Finlandiae XV Suomen keskiajan arkeologian seura – Sällskapet för medeltidsarkeologi i Finland Janne Harjula Before the Heels Footwear and Shoemaking in Turku in the Middle Ages and at the Beginning of the Early Modern Period Suomen keskiajan arkeologian seura Turku Editorial Board: Anders Andrén, Knut Drake, David Gaimster, Georg Haggrén, Markus Hiekkanen, Werner Meyer, Jussi-Pekka Taavitsainen and Kari Uotila Editor Janne Harjula Language revision Colette Gattoni Layout Jouko Pukkila Cover design Janne Harjula and Jouko Pukkila Published with the kind support of Emil Aaltonen Memorial Fund and Fingrid Plc Cover image Reconstruction of a medieval shoemaker’s workshop. Produced for an exhibition introducing the 15th and 16th centuries. Technical realization: Schweizerisches Waffeninstitut Grandson. Photograph: K. P. Petersen. © 1987 Museum für Vor- und Frühgeschichte SMPK Berlin. Back cover images Children’s shoes from excavations in Turku. Janne Harjula/Turku Provincial Museum. ISBN: ISSN: 1236-5882 Saarijärven Offset Oy Saarijärvi 2008 5 CONTENTS Preface 9 Introduction 11 Questions and the definition of the study 12 Research history 13 Material and methodology 17 PART I: FOOTWEAR 21 1. SHOE TYPES IN TURKU 21 1.1 One-piece shoes 22 1.1.1 The type definition and research history of one-piece shoes in Turku 22 1.1.2 The number and types of one-piece shoes 22 1.1.2.1 Cutting patterns -

Ref. Wxdoctor

My name is Keith Heidorn. If you asked me to describe myself in the context of the Weather Doctor, I would tell you that I am both an artist and a scientist who is deeply involved with the weather and other atmospheric phenomena on many levels. I have had a love affair with the weather for about 45 years. You see, I think that weather is the most sensual aspect of life, stimulating all my senses at one time or another and often several at once. I was born in Chicago and grew up in northeastern Illinois where I first fell in love with the weather. The Great Lakes region has its variety of weather extremes generally with a rapid turnover of daily weather events. http://www.glenallenweather.com/historylinks/wxdoc/jan.htm Ref. Weather Doctor United States 1 April 1923, Eastern States: Residents awake to "April Fool's Day" bitterly cold temperatures: -34 °F (-36.7 °C) at Bergland Michigan and to 16 °F (-8.9 °C) in Georgia. 1 April 1987, White Fish Bay, Wisconsin: Tornado strikes during a snow squall and damages a mobile home. 2 April 1975, Chicago, Illinois: O'Hare Airport is closed as 10.9 inches (27.7 cm) of snow buries the Windy City. The storm is the city's biggest snowstorm so late in season, dumping as much as 20 inches (51 cm) across northeastern Illinois. 2 April 2006, Central Mississippi Valley/Ohio Valley: Widespread severe weather produces a major tornadic outbreak As many as 86 tornadoes are reported across Iowa, Illinois, Missouri, Arkansas, Kentucky, Indiana and Tennessee. -

Sagawkit Acceptancespeechtran

Screen Actors Guild Awards Acceptance Speech Transcripts TABLE OF CONTENTS INAUGURAL SCREEN ACTORS GUILD AWARDS ...........................................................................................2 2ND ANNUAL SCREEN ACTORS GUILD AWARDS .........................................................................................6 3RD ANNUAL SCREEN ACTORS GUILD AWARDS ...................................................................................... 11 4TH ANNUAL SCREEN ACTORS GUILD AWARDS ....................................................................................... 15 5TH ANNUAL SCREEN ACTORS GUILD AWARDS ....................................................................................... 20 6TH ANNUAL SCREEN ACTORS GUILD AWARDS ....................................................................................... 24 7TH ANNUAL SCREEN ACTORS GUILD AWARDS ....................................................................................... 28 8TH ANNUAL SCREEN ACTORS GUILD AWARDS ....................................................................................... 32 9TH ANNUAL SCREEN ACTORS GUILD AWARDS ....................................................................................... 36 10TH ANNUAL SCREEN ACTORS GUILD AWARDS ..................................................................................... 42 11TH ANNUAL SCREEN ACTORS GUILD AWARDS ..................................................................................... 48 12TH ANNUAL SCREEN ACTORS GUILD AWARDS .................................................................................... -

The Complete Stories

The Complete Stories by Franz Kafka a.b.e-book v3.0 / Notes at the end Back Cover : "An important book, valuable in itself and absolutely fascinating. The stories are dreamlike, allegorical, symbolic, parabolic, grotesque, ritualistic, nasty, lucent, extremely personal, ghoulishly detached, exquisitely comic. numinous and prophetic." -- New York Times "The Complete Stories is an encyclopedia of our insecurities and our brave attempts to oppose them." -- Anatole Broyard Franz Kafka wrote continuously and furiously throughout his short and intensely lived life, but only allowed a fraction of his work to be published during his lifetime. Shortly before his death at the age of forty, he instructed Max Brod, his friend and literary executor, to burn all his remaining works of fiction. Fortunately, Brod disobeyed. Page 1 The Complete Stories brings together all of Kafka's stories, from the classic tales such as "The Metamorphosis," "In the Penal Colony" and "The Hunger Artist" to less-known, shorter pieces and fragments Brod released after Kafka's death; with the exception of his three novels, the whole of Kafka's narrative work is included in this volume. The remarkable depth and breadth of his brilliant and probing imagination become even more evident when these stories are seen as a whole. This edition also features a fascinating introduction by John Updike, a chronology of Kafka's life, and a selected bibliography of critical writings about Kafka. Copyright © 1971 by Schocken Books Inc. All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. Published in the United States by Schocken Books Inc., New York. Distributed by Pantheon Books, a division of Random House, Inc., New York. -

Seasons Change. Quality Endures

SEASONS CHANGE. QUALITY ENDURES. SPRING STYLES 2015 WARWICK AND ROGUE IN WALNUT (PAGE 8) HANDCRAFTED SPRING HAS SPRUNG A LEGACY WORTH CARRYING ON Artic blast. Polar vortex. Snowmageddon—winter these days feels more like a horror movie or disaster flick than a season. But your reward for the cold temps, icy winds and record snowfall is here: our Spring catalog featuring our latest designs perfect for the new year and the new you. With the weather transitioning from cold to warm you need to be prepared for anything. That means having a pair of our shoes with an all-weather Dainite sole. Made of rubber and studded for extra grip without the extra grime that comes with ridging, these soles let you navigate April showers without breaking your stride. Speaking of breaks, spring is a great time for one. If you are out on the open road or hopping on a plane, the styles in our Drivers Collection are comfortable and convenient travel footwear. Available in a variety of designs and colors, there is one For nearly a century we have (or more) to match your destination as well as your personality. PAGE 33 PAGE 14 continued to adhere to our 212-step manufacturing process Enjoy the Spring catalog and the sunnier days ahead. because great craftsmanship cannot and should not be Warm regards, rushed. To that end, during upper sewing, our skilled cutters and sewers still create the upper portion of each shoe by hand using time-tested methods, hand-cut pieces of leather PAUL GRANGAARD and dependable, decades-old President and CEO sewing machines. -

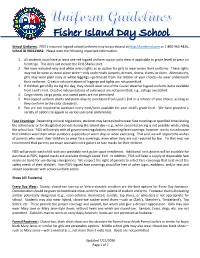

2020-2021 School Uniforms

Fisher Island Day School School Uniforms: FIDS’s required, logoed school uniforms may be purchased at http://landsend.com or 1-800-963-4816, School ID 900123852. Please note the following important information: 1. All students must have at least one red logoed uniform top (or polo dress if applicable to grade level) to wear on field trips. This does not include the FIDS Sharks shirt. 2. We have included navy and white micro tights as an option for girls to wear under their uniforms. These tights may not be worn as stand-alone attire—only underneath jumpers, dresses, shorts, skorts, or skirts. Alternatively, girls may wear plain navy or white leggings—purchased from the retailer of your choice—to wear underneath their uniforms. Creative interpretations of leggings and tights are not permitted. 3. If children get chilly during the day, they should wear one of the Cooler Weather logoed uniform items available from Land’s End. Creative interpretations of outerwear are not permitted; e.g., college sweatshirt. 4. Cargo shorts, cargo pants, and sweat pants are not permitted. 5. Non-logoed uniform shorts and pants may be purchased from Land’s End or a retailer of your choice, as long as they conform to the color standards. 6. You are not required to purchase every item/color available for your child’s grade level. We have provided a variety of options to appeal to various personal preferences. Face Coverings: Depending on local regulations, students may be required to wear face coverings at specified times during the school year or for designated periods during the school day—e.g., when social distancing is not possible while; riding the school bus.