Tobias Revised 140115 (Clean) Kopia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fredrik Reinfeldt

2014 Press release 03 June 2014 Prime Minister's Office REMINDER: German Chancellor Angela Merkel, British Prime Minister David Cameron and Dutch Prime Minister Mark Rutte to Harpsund On Monday and Tuesday 9-10 June, Prime Minister Fredrik Reinfeldt will host a high-level meeting with German Chancellor Angela Merkel, British Prime Minister David Cameron and Dutch Prime Minister Mark Rutte at Harpsund. The European Union needs to improve job creation and growth now that the EU is gradually recovering from the economic crisis. At the same time, the EU is facing institutional changes with a new European Parliament and a new European Commission taking office in the autumn. Sweden, Germany, the UK and the Netherlands are all reform and growth-oriented countries. As far as Sweden is concerned, it will be important to emphasise structural reforms to boost EU competitiveness, strengthen the Single Market, increase trade relations and promote free movement. These issues will be at the centre of the discussions at Harpsund. Germany, the UK and the Netherlands, like Sweden, are on the World Economic Forum's list of the world's ten most competitive countries. It is natural, therefore, for these countries to come together to compare experiences and discuss EU reform. Programme points: Monday 9 June 18.30 Chancellor Merkel, PM Cameron and PM Rutte arrive at Harpsund; outdoor photo opportunity/door step. Tuesday 10 June 10.30 Joint concluding press conference. Possible further photo opportunities will be announced later. Accreditation is required through the MFA International Press Centre. Applications close on 4 June at 18.00. -

Galamiddag Hos Dd.Mm. Konungen Och Drottningen På Stockholms Slott Tisdagen Den 1 Oktober 2013, Kl

GALAMIDDAG HOS DD.MM. KONUNGEN OCH DROTTNINGEN PÅ STOCKHOLMS SLOTT TISDAGEN DEN 1 OKTOBER 2013, KL. 20.00 MED ANLEDNING AV STATSBESÖK FRÅN PORTUGAL. H.M. Konungen H.M. Drottningen H.K.H. Kronprinsessan Victoria H.K.H. Prins Daniel H.K.H. Prins Carl Philip HEDERSGÄSTER: His Excellency the President of the Portuguese Republic, Professor Aníbal Cavaco Silva and Mrs. Maria Cavaco Silva Officiell svit: Mr Rui Machete, Minister of State and for Foreign Affairs Mr António Pires de Lima, Minister for Economy Ambassador Manuel Marcelo Curto, Ambassador of Portugal to Sweden and Mrs Irina Marcelo Curto, Portugal Mr Nuno Magalhães, MP Chairman of the Parliamentary Group of the Democratic Social Centre-Popular Party Ms Maria Leonor Beleza, President of the Champalimaud Foundation Ms Francisca Almeida, MP representative of the Social Democratic Party Ms Odete João, MP representative of the Socialist Party Mr Jorge Machado, MP representative of the Communist Party Mr José Nunes Liberato, Head of the Civil House of the Presidency Ambassador António Almeida Lima, Chief of State Protocol Ambassador Luísa Bastos de Almeida, Presidential Adviser for International Relations Mr Nuno Sampaio, Presidential Adviser for Parliamentary Affairs and Local Government Ms Margarida Mealha, Adviser at the First Lady´s Office Mr José Carlos Vieira, Presidential Adviser for the Media Mr Jorge Silva Lopes, Deputy Chief of State Protocol Mr Mário Martins, Presidential Consultant for International Relations and Portuguese Communities Ms Maria Manuel Morais e Silva, Presidential -

How Sweden Is Governed Content

How Sweden is governed Content The Government and the Government Offices 3 The Prime Minister and the other ministers 3 The Swedish Government at work 4 The Government Offices at work 4 Activities of the Government Offices 5 Government agencies 7 The budget process 8 The legislative process 8 The Swedish social model 10 A democratic system with free elections 10 The Swedish administrative model – three levels 10 The Swedish Constitution 11 Human rights 12 Gender equality 12 Public access 13 Ombudsmen 13 Scrutiny of the State 14 Sweden in the world 15 Sweden and the EU 15 Sweden and the United Nations 15 Nordic cooperation 16 Facts about Sweden 17 Contact 17 2 HOW SWEDEN IS GOVERNED How Sweden is governed The Government and the Government Offices The Prime Minister and the other ministers Sweden is governed by a centre-right minority government elected in 2010 and composed of representatives of four parties: the Moderate Party, the Centre Party, the Swedish Christian Democrats and the Liberal Party. The Government consists of a prime minister and 23 ministers, each with their own portfolio. Fredrik Reinfeldt Prime Minister Lena Adelsohn Liljeroth Minister for Culture and Sports Maria Arnholm Minister for Gender Equality Beatrice Ask Minister for Justice Stefan Attefall Minister for Public Administration and Housing Carl Bildt Minister for Foreign Affairs Tobias Billström Minister for Migration and Asylum Policy Jan Björklund Minister for Education Ewa Björling Minister for Trade Anders Borg Minister for Finance Lena Ek Minister for the -

SFS Verksamhetsberättelse 0910

Dnr: O47-1/1011 SFS Verksamhetsberättelse 2009/2010 Innehållsförteckning INNEHÅLLSFÖRTECKNING ........................................................................................................................... 2 INLEDNING ......................................................................................................................................................... 4 SVERIGES FÖRENADE STUDENTKÅRERS STYRELSE 2009/2010 ......................................................... 5 Arbetsgrupper ................................................................................................................................................ 5 FORTSATT STARKT STUDENTINFLYTANDE ............................................................................................ 6 HELTID ÄR HELTID ........................................................................................................................................ 12 Arbetet för en bättre grundutbildning .......................................................................................................... 12 Ett kvalitetsbaserat resurstilldelningssystem ............................................................................................... 16 ÖVRIGA STÖRRE FRÅGOR ........................................................................................................................... 19 Studievgifter för högre utbildning ............................................................................................................... 19 Autonomipropositionen .............................................................................................................................. -

A Quantitative and Qualitative Study of the Impact of Swedish Foreign Aid on the Palestinian Economy

STOCKHOLM UNIVERSITY Department of Economic History and International Relations Master's Thesis in International Relations with specialization in Global Political Economy Spring Term 2021 Student: Waris Miratif Supervisor: Jonathan Michael Feldman A Quantitative and Qualitative Study of The Impact of Swedish Foreign Aid on the Palestinian Economy Keywords: Aid Effectiveness, Economic Growth, Two-Gap Model, Corruption, Occupation i Abstract This thesis contributes to the scholarship on aid effectiveness by evaluating the economic impact of Swedish foreign aid on the Palestinian economy (GDP) from 1999 to 2019. Econometric approaches have often been used in previous studies to assess aid effectiveness, but they are not sufficient for establishing clear conclusions, especially in a unique conflict- affected economy such as Palestine. Therefore, this study combines a mixed methods research approach involving qualitative and quantitative approaches. The primary research question is: “To what extent has Swedish foreign aid significantly contributed to the Palestinian economy during the past two decades from 1999-2019?” Two sub-questions follow the main research question: “To what extent has aid effectiveness in Palestine been affected by corruption in the Palestinian Authority and the Israeli occupation during the past two decades. The thesis uses a two-gap model of the economic growth theory by employing different techniques like inferential and descriptive statistics (quantitative research) followed by a content analysis and interviews (qualitative research) to answer the research questions. Results from the descriptive and inferential statistics and the content analysis show that Swedish aid positively affects the Palestinian economy but is limited by countervailing factors. The effectiveness of aid is constrained by the Israeli occupation and corruption in the Palestinian Authority (PA). -

In International Waters How Europe Can Strengthen Global Research Efforts CONTENTS

www.publicservice.co.uk European Science & Technology 15 an independent review Helga Nowotny Astrid Krag Maria Damanaki Anne Glover comments on collaboration with highlights opportunities for discusses marine developments on bringing the scientific international partners innovation in healthcare and Blue Growth evidence base to policymaking In international waters How Europe can strengthen global research efforts CONTENTS Peter Tindemans, Secretary General, Euroscience . 3 FOREWORD 3 Lauren Smith, Editor . 4 INTRODUCTION 4 How can collaboration between European and international partners be strengthened?. 9 DIGEST 9 RESEARCH A clearer path to prominence . 18 FEATURE INTERVIEW 18 Editor Lauren Smith talks to Professor Anne Glover, Chief Scientific Adviser to the European Commission, about her role in helping Europe realise its considerable innovation ambitions in the coming years Localised thinking . 22 OVERVIEW 22 European Commissioner for Regional Policy Johannes Hahn discusses how Europe’s 2020 goals can be realised through concentrating resources on the regions Banking on ‘Big Data’ . 32 All the evidence points to the development of a Digital Single Market being instrumental in future growth, as DIGITALEUROPE Director-General John Higgins highlights Ireland of opportunity. 38 Irish Minister for Research and Innovation Sean Sherlock sheds light on efforts to maximise the impact of investment Engineering excellence . 44 FEANI is committed to promoting collaborative working, representing engineers and encouraging progress, as Public Service Review explores A measure of intelligence . 48 Professor Austin Tate, Director of the AIAI, details the reality, successes and hopes for the future for artificial intelligence Granting our wishes. 52 The European Economics Association’s Mike Mariathasan and Ramon Marimon provide the economists’ perspective on research funding Hedging your vets . -

New Cooperation Agreement with India

2012 Press release 26 November 2012 Ministry of Health and Social Affairs New cooperation agreement with India Today, 26 November 2012, Sweden and India have signed a social insurance agreement that makes it easier for Swedish citizens to work in India and for Indian citizens to work in Sweden. Similar negotiations are taking place with Japan, China and South Korea. The agreement coordinates the general Indian and Swedish old-age, survivors' and disability pensions systems. It determines whether a person is to be insured in India or Sweden, thus preventing people losing the rights they have acquired and social security contributions being paid in both countries. Download The Social Security The agreement is important given that more than one hundred Swedish companies are operating in India, and Agreement between India and the number is growing every year. Sweden has similar agreements with ten other countries: Bosnia and Sweden (pdf 51 kB) Herzegovina, Canada, Cape Verde, Chile, Croatia, Israel, Morocco, Serbia, Turkey and the United States. Under the agreement, employees can be sent from their home country to work for the company in the other country for two years at the most (can be extended by a further two years). They continue to be insured for old-age, survivors' and disability pensions in their home country and pay their social insurance contributions for these insurances there. An estimated 500 Swedish citizens live in India. About 160 Swedish companies are registered in India. In addition, about 1 000 Swedish companies do business in and with the country. Roughly 8 000 Indian citizens and 20 000 people of Indian origin live in Sweden. -

Hon Är Favorit Till Att Bli Liberalernas Nästa Partiledare

Hon är favorit till att bli Liberalernas nästa partiledare Igår meddelade Jan Björklund att han avgår som Liberalernas partiledare, och nu kan Unibet presentera odds på vem som tar över efter den gamle majoren. Favorit i oddslistan är Nyamko Sabuni, tätt följd av Cecilia Malmström och Mats Persson. Efter att Jan Björklund meddelade sin avgång har spekulationerna kring vem som ska ta över ordförandeskapet för L rullat igång. Enligt oddsen från Unibet är det ovisst, med knappt favoritskap för Nyamko Sabuni, Cecilia Malmström och Mats Persson. Blir det Sabuni eller Malmström som tar över är det blott andra gången en kvinna styr partiet. – Liberalerna har endast haft en kvinnlig partiledare, och det var Maria Leissner under andra halvan av 90-talet. Sabuni är knapp favorit, men det är oerhört jämnt i oddslistan, och bakom topptrion återfinns exempelvis Birgitta Ohlsson, säger Henrik Holm, spelexpert på Unibet. Birgitta Ohlsson spelas till oddset 5.00, precis som den förre partisekreteraren Johan Pehrson. Den nuvarande partisekreteraren Maria Arnholm står i oddset 10.00, och ett spel på den förre integrationsministern Erik Ullenhag ger 15 gånger pengarna. – Birgitta Ohlsson är ju den som de senaste åren legat närmast till hands att efterträda Björklund. Det blir väldigt intressant att se vem som blir ny partiledare, Ohlsson är inte speciellt långt efter i oddslistan och kanske är det hennes tur nu, säger Henrik Holm, spelexpert på Unibet. Unibet odds på vem som blir Liberalernas nästa partiledare: Nyamko Sabuni 4.50 Cecilia Malmström 4.75 Mats Persson 4.75 Birgitta Ohlsson 5.00 Johan Pehrson 5.00 Gulan Avci 5.50 Maria Arnholm 10.00 Erik Ullenhag 15.00 Se uppdaterade odds här: https://www.unibet.se/betting#filter/politics/sweden/in_the_spotlight/1005291630 För mer information, vänligen kontakta: Henrik Holm, spelexpert på Unibet, 070-875 41 31, [email protected] Om Unibet Unibet grundades 1997 och är en del av Kindred Group, en speloperatör noterat på Nasdaq Stockholm. -

Nyamko Sabuni +46 8 405 10 00

2011 Press release 21 September 2011 Ministry of Education and Research Major investments in education in the Budget Bill The Budget Bill contains major investments in education. These include a maths boost with continuing professional development for teachers, a teacher reform with career stages for good teachers, a quality drive in humanities and social sciences at higher education institutions, and more places on training programmes for doctors, dentists and nurses. More places will also be available on Master of Science in Engineering programmes. Below is a description of the most important reforms in the area of education in this autumn's budget. Higher status for the teaching profession and improved skills in schools To break the downward trend in learning outcomes among Swedish pupils, it is necessary to strengthen teachers' skills and the status of the teaching profession. In the Budget Bill, SEK 3.8 billion has been allocated for the years 2012-2015 to strengthen teachers' skills and raise the status of the teaching profession. Career development reform The Government is allocating funds for a career development reform, with advancement stages for professionally skilled teachers in compulsory and upper secondary school. The advancement stages, together with any qualifications required, will be described in the Education Act. Salaries and terms of employment will be set by the parties in the usual way. The state will cover the costs incurred by education authorities through the reform in the form of government grants. Boost for Teachers II Boost for Teachers II is being introduced. This is an investment in continuing professional development, which will mean that teachers who have accreditation but are not qualified in one of the subjects or for one of the year groups they teach will be offered education to meet the qualification requirements. -

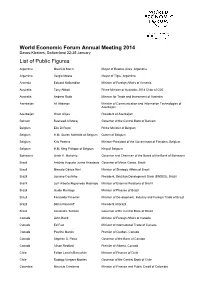

List of Public Figures

World Economic Forum Annual Meeting 2014 Davos-Klosters, Switzerland 22-25 January List of Public Figures Argentina Mauricio Macri Mayor of Buenos Aires, Argentina Argentina Sergio Massa Mayor of Tigre, Argentina Armenia Edward Nalbandian Minister of Foreign Affairs of Armenia Australia Tony Abbott Prime Minister of Australia; 2014 Chair of G20 Australia Andrew Robb Minister for Trade and Investment of Australia Azerbaijan Ali Abbasov Minister of Communication and Information Technologies of Azerbaijan Azerbaijan Ilham Aliyev President of Azerbaijan Bahrain Rasheed Al Maraj Governor of the Central Bank of Bahrain Belgium Elio Di Rupo Prime Minister of Belgium Belgium H.M. Queen Mathilde of Belgium Queen of Belgium Belgium Kris Peeters Minister-President of the Government of Flanders, Belgium Belgium H.M. King Philippe of Belgium King of Belgium Botswana Linah K. Mohohlo Governor and Chairman of the Board of the Bank of Botswana Brazil Antônio Augusto Junho Anastasia Governor of Minas Gerais, Brazil Brazil Marcelo Côrtes Neri Minister of Strategic Affairs of Brazil Brazil Luciano Coutinho President, Brazilian Development Bank (BNDES), Brazil Brazil Luiz Alberto Figueiredo Machado Minister of External Relations of Brazil Brazil Guido Mantega Minister of Finance of Brazil Brazil Fernando Pimentel Minister of Development, Industry and Foreign Trade of Brazil Brazil Dilma Rousseff President of Brazil Brazil Alexandre Tombini Governor of the Central Bank of Brazil Canada John Baird Minister of Foreign Affairs of Canada Canada Ed Fast Minister -

Föredragningslista

Föredragningslista 2009/10:125 Tisdagen den 25 maj 2010 Kl. (uppehåll för gruppmöten ca kl. 16.00-18.00) 13.00 Interpellationssvar ____________________________________________________________ Justering av protokoll 1 Protokollet från sammanträdet onsdagen den 19 maj Meddelande om frågestund Torsdagen den 27 maj kl.14.00 2 Följande statsråd kommer att delta: Näringsminister Maud Olofsson (c) Finansminister Anders Borg (m) Kulturminister Lena Adelsohn Liljeroth (m) Statsrådet Tobias Krantz (fp) Statsrådet Birgitta Ohlsson (fp) Meddelande om ändring i kammarens sammanträdesplan Måndagen den 14 juni 3 Arbetsplenum tidigareläggs och börjar kl. 9.00 Anmälan om fördröjda svar på interpellationer 4 2009/10:357 av Alf Eriksson (s) Statligt stöd till ny kärnkraft 5 2009/10:367 av Peter Eriksson (mp) Elcertifikat till gammal elproduktion 6 2009/10:387 av Thomas Strand (s) Folkhögskolelärares behov av Lärarlyftet 7 2009/10:388 av Hans Stenberg (s) Vattenskotrar 8 2009/10:396 av Jasenko Omanovic (s) Specialpedagogiska skolmyndigheten 9 2009/10:404 av Lennart Axelsson (s) Försäljning av receptfria läkemedel 1 (4) Tisdagen den 25 maj 2010 ______________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ Svar på interpellationer Interpellationer upptagna under samma punkt besvaras i ett sammanhang Justitieminister Beatrice Ask (m) 10 2009/10:285 av Peter Hultqvist (s) Lagrådets kritik mot regeringens lagförslag 11 2009/10:379 av Carina Adolfsson Elgestam (s) Granskningskommission inom -

Annual Report 2006 Every Human Being Is Entitled to a Life in Dignity

Annual Report 2006 Every human being is entitled to a life in dignity. This has been agreed by the nations of the world in the Universal Declaration on Human Rights. The rights perspective and the perspectives of the poor constitute the points of departure of Sweden’s policy for global development. Sida works on the basis of these perspectives to strengthen the possibilities available to poor people to assert their rights and interests. We work to strengthen the right of poor people to participate in decisions and to counteract discrimination. Poverty has many different causes and expressions. Sida’s work is therefore always being adapted to the situation in question. Some of the fields that are important to work with to reduce poverty are protection of the environment and sustainable development; peace and security; democracy; equality between women and men; social development, and economic growth. Development must always be driven by the society in which it takes place. Annual Report 2006 Contents Introduction ................................................................7 Sida’s organisation ...........................................................10 Sida’sboard................................................................11 Members of Sida’s Research Council . .............................................12 Sida’s management 2006 . ...................................................12 Policy area: International development cooperation . ..........................13 Goals, perspectives and central component elements in development