Doing and Undoing Child Marriage in Nepal

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

District Census Handbook, 48-Deoria, Uttar Pradesh

CENSUS 1961 DISTRICT CENSUS HANDBOOK UTT AR PR~DESH 48-DEORIA DISTRICT LUCKNOW Supcrlntcmtent, Printing and S1J.d:nOlw·y, lJ. P ..( India) 1965 Price Rs. 10.00 CONTENTS Pages i-viij I-CENSUS TABLES A-,-GENERAL POPULATION TA6,LES Area, Houses and Population II-Number of Villages, with a Population of 5,000 and ove~ and Towns with & Popul~tion under 5,000 6 III-Houseless and Institutional Population 6 Variation in Population during Sigty Years 1 1951 ropulation according to the territorial jurisdiction in 1951 and changes in area and population involved in those changes 7 Villages Classified by Population 8 • I • Towns (and Town-groups) classified by Population I io, 1!:lp1 with Variation since 1941 9 \ , New Towns added in 1961 and Towns in 1951 declassified in 1961 10 , } t (" Explanatory Note to the Appendix 10 I B-GENERAL ECONOMIC TABLES Workers and Non-workers in District and Towns classified by Sex and Broad Age-groups 12 Part A-lndustrial Classification of Workers and Non-workers by Educational Levels in Urban Areas oniy 16 Part B-Industrial Classification of Workers and Non-workers by Educp.tional Levels in Rural Areas only 18 Part A-Industrial Classification by Sex and Class of Worker of Persons at Work at Household Industry 22 Part B-Industrial Classification by Sex and Class of Worker of Persons at Work in Non-household Industry~ Trade, Business, Profession or Service 26 Part C-Inaustrial Classification by Sex and Divisions, Major Groups and Minor Groups of Persons at Work other than Cultivation 34 Occupational Clas.sification -

Endline Study Sakcham - III Project

Endline Study Sakcham - III Project Endline Evaluation Report Submitted by Nepal Evaluation & Assessment Team (NEAT) Kathmandu, Nepal Submitted to CARE Nepal February, 2016 Kathmandu Endline Evaluation of Sakcham - III Project Page | 1 Table of Contents List of Abbreviations ................................................................................................................... 3 Acknowledgements .................................................................................................................... 4 Executive Summary ................................................................................................................... 5 1. Introduction ........................................................................................................................10 1.1 Background.................................................................................................................10 1.2 Context .......................................................................................................................11 1.3 Study Objectives .........................................................................................................13 2. Methodology ......................................................................................................................14 2.1 Study Design ..............................................................................................................14 2.2 Study Scope ...............................................................................................................17 -

![Ltzt Ul/Alsf Uxgtf -K|Ltzt Slknj:T Uh]X8f, Jf0fu+Uf](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/7956/ltzt-ul-alsf-uxgtf-k-ltzt-slknj-t-uh-x8f-jf0fu-uf-417956.webp)

Ltzt Ul/Alsf Uxgtf -K|Ltzt Slknj:T Uh]X8f, Jf0fu+Uf

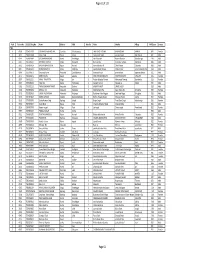

1 2 lhNnfx?sf] ul/aLsf] b/, ul/aLsf] ljifdtf / ul/aLsf] uxgtf @)^* lhNnf uf=lj=;=sf gfd ul/aLsf b/ ul/aLsf ljifdtf ul/aLsf uxgtf -k|ltzt_ -k|ltzt_ -k|ltzt_ slknj:t uh]x8f, jf0fu+uf 10(2.63) 1.88(0.61) 0.55(0.21) slknj:t km'lnsf 38.67(6.03) 9.36(2.02) 3.27(0.87) slknj:t xyf};f 17.49(3.71) 3.69(1.01) 1.17(0.38) slknj:t gGbgu/, afF;vf]/, ktl/of 45.04(6.34) 11.38(2.33) 4.07(1.03) slknj:t k6gf 31.98(5.78) 7.21(1.76) 2.38(0.7) slknj:t ljh'jf 41.77(6.05) 10.4(2.16) 3.68(0.95) slknj:t xlyxjf, njgL, lj7'jf 48.86(6.3) 13.11(2.52) 4.9(1.17) slknj:t lkk/f 39.97(6.41) 9.82(2.18) 3.48(0.95) slknj:t cle/fj, 8'd/f 39.5(6.11) 9.6(2.04) 3.37(0.86) slknj:t x/gfdk'/, an'xjf 38.43(6.46) 9.11(2.1) 3.14(0.87) slknj:t ks8L 40.75(6.14) 9.92(2.13) 3.45(0.91) slknj:t ltltlv 45.45(6.55) 11.69(2.34) 4.26(1.03) slknj:t sf]kjf 13.51(3.2) 2.68(0.76) 0.82(0.27) slknj:t df]ltk'/ 8.87(2.35) 1.71(0.56) 0.51(0.2) slknj:t lglUnxjf 24.73(4.91) 5.42(1.38) 1.78(0.53) slknj:t ltnf}/fsf]6 32.55(5.83) 7.4(1.8) 2.46(0.73) slknj:t w/dklgof 42.73(6.42) 10.72(2.24) 3.84(0.98) slknj:t hxbL 41.96(5.92) 10.5(2.03) 3.76(0.88) slknj:t k/;f]lxof, a;Gtk'/ 40.97(6.66) 9.95(2.27) 3.48(0.97) slknj:t bf]xgL,/+uk'/ 41.51(6.41) 10.28(2.23) 3.66(0.96) slknj:t uf}/L 46.11(6.78) 11.44(2.41) 4.04(1.05) slknj:t l;+xf]vf]/, a}bf}nL, ;fdl8x 42.23(6.45) 10.67(2.32) 3.84(1.02) slknj:t uf]l7xjf 41.2(6.47) 10.26(2.19) 3.68(0.95) slknj:t ;f}/fxf 47.79(6.88) 12.4(2.57) 4.51(1.16) slknj:t /fhk'/, dx'jf, wgsf}nL 43.49(5.84) 11.19(2.18) 4.06(0.98) slknj:t hogu/, enjf8 16.32(3.56) 3.39(0.94) 1.06(0.35) slknj:t -

Bangad Kupinde Municipality Profile 2074, Salyan All.Pdf

aguf8 s'lk08] gu/kflnsf aguf8 s'lk08] gu/ sfo{kflnsfsf] sfof{no ;Nofg, ^ g+= k|b]z, g]kfn gu/ kfZj{lrq @)&$ c;f/ b'O{ zAb o; gu/kflnsf cGtu{t /x]sf ;fljs b]j:yn, afd], 3fFem/Llkkn, d"nvf]nf uf=lj=;= df k|rlnt aGuf8L ;F:s[lt / ;Nofg lhNnfnfO{ g} /fli6«o tyf cGt/f{li6«o ¿kdf lrgfpg ;kmn s'lk08]bxsf] ;+of]hgaf6 gfdfs/0f ul/Psf] aguf8 s'lk08] gu/kflnsfsf] klxnf] k|sflzt b:tfj]hsf] ¿kdf cfpg nfu]sf] kfZj{lrq 5f]6f] ;dod} tof/L ug{ kfpFbf cToGt} v';L nfu]sf] 5 . /fHosf] k'g;{+/rgfsf] l;nl;nfdf :yflkt o; gu/kflnsfsf] oyfy{ ljBdfg cj:yf emNsfpg] kfZj{lrq tof/Ln] gu/sf] ljsf;sf] jt{dfg cj:yfnO{ lrlqt u/]sf] 5 . o:tf] lrq0fn] cfufdL lbgdf xfdLn] th'{df ug'{kg]{ gLlt tyf sfo{qmdx¿nfO{ k|fyldsLs/0f u/L xfdLnfO{ pknAw ;Lldt >f]t tyf ;fwgsf] clwstd ;b'kof]u u/L gu/ ljsf;nfO{ ult k|bfg ug{ cjZo klg ;xof]u k'¥ofpg] cfzf tyf ljZjf; lnPsf] 5' . o; cWoog k|ltj]bgn] k|foM ;a} If]q tyf j:t'ut oyfy{nfO{ ;d]6\g k|of; u/]sf] ePtfklg ;Lldt ;do tyf ;|f]t ;fwgsf] ;Ldfleq ul/Psf] cWoog cfkm}df k"0f{ x'g ;Sb}g . o;nfO{ ;do ;Gbe{cg';f/ kl/is[t / kl/dflh{t ug]{ bfloTj xfd|f] sfFwdf cfPsf] dxz'; xfdL ;a}n] ug'{ kg]{ x'G5 . of]hgfj4 ljsf;sf] cfwf/sf] ¿kdf /xg] of] kfZj{lrq ;dod} tof/ ug{ nufpg] gu/ sfo{kflnsfsf] ;Dk"0f{ l6d, sfo{sf/L clws[t tyf cGo j8f txdf dxTjk"0f{ lhDd]jf/L k'/f ug]{ sd{rf/L Pj+ lgjf{lrt hgk|ltlglw nufot tYofÍ pknAw u/fpg] ;Dk"0f{ ljifout sfof{no, ;+3;+:yf tyf cGo ;a}df gu/kflnsfsf] tkm{af6 cfef/ k|s6 ug{ rfxG5' . -

Food Insecurity and Undernutrition in Nepal

SMALL AREA ESTIMATION OF FOOD INSECURITY AND UNDERNUTRITION IN NEPAL GOVERNMENT OF NEPAL National Planning Commission Secretariat Central Bureau of Statistics SMALL AREA ESTIMATION OF FOOD INSECURITY AND UNDERNUTRITION IN NEPAL GOVERNMENT OF NEPAL National Planning Commission Secretariat Central Bureau of Statistics Acknowledgements The completion of both this and the earlier feasibility report follows extensive consultation with the National Planning Commission, Central Bureau of Statistics (CBS), World Food Programme (WFP), UNICEF, World Bank, and New ERA, together with members of the Statistics and Evidence for Policy, Planning and Results (SEPPR) working group from the International Development Partners Group (IDPG) and made up of people from Asian Development Bank (ADB), Department for International Development (DFID), United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), UNICEF and United States Agency for International Development (USAID), WFP, and the World Bank. WFP, UNICEF and the World Bank commissioned this research. The statistical analysis has been undertaken by Professor Stephen Haslett, Systemetrics Research Associates and Institute of Fundamental Sciences, Massey University, New Zealand and Associate Prof Geoffrey Jones, Dr. Maris Isidro and Alison Sefton of the Institute of Fundamental Sciences - Statistics, Massey University, New Zealand. We gratefully acknowledge the considerable assistance provided at all stages by the Central Bureau of Statistics. Special thanks to Bikash Bista, Rudra Suwal, Dilli Raj Joshi, Devendra Karanjit, Bed Dhakal, Lok Khatri and Pushpa Raj Paudel. See Appendix E for the full list of people consulted. First published: December 2014 Design and processed by: Print Communication, 4241355 ISBN: 978-9937-3000-976 Suggested citation: Haslett, S., Jones, G., Isidro, M., and Sefton, A. (2014) Small Area Estimation of Food Insecurity and Undernutrition in Nepal, Central Bureau of Statistics, National Planning Commissions Secretariat, World Food Programme, UNICEF and World Bank, Kathmandu, Nepal, December 2014. -

Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA)

Chapter 3 Project Evaluation and Recommendations 3-1 Project Effect It is appropriate to implement the Project under Japan's Grant Aid Assistance, because the Project will have the following effects: (1) Direct Effects 1) Improvement of Educational Environment By replacing deteriorated classrooms, which are danger in structure, with rainwater leakage, and/or insufficient natural lighting and ventilation, with new ones of better quality, the Project will contribute to improving the education environment, which will be effective for improving internal efficiency. Furthermore, provision of toilets and water-supply facilities will greatly encourage the attendance of female teachers and students. Present(※) After Project Completion Usable classrooms in Target Districts 19,177 classrooms 21,707 classrooms Number of Students accommodated in the 709,410 students 835,820 students usable classrooms ※ Including the classrooms to be constructed under BPEP-II by July 2004 2) Improvement of Teacher Training Environment By constructing exclusive facilities for Resource Centres, the Project will contribute to activating teacher training and information-sharing, which will lead to improved quality of education. (2) Indirect Effects 1) Enhancement of Community Participation to Education Community participation in overall primary school management activities will be enhanced through participation in this construction project and by receiving guidance on various educational matters from the government. 91 3-2 Recommendations For the effective implementation of the project, it is recommended that HMG of Nepal take the following actions: 1) Coordination with other donors As and when necessary for the effective implementation of the Project, the DOE should ensure effective coordination with the CIP donors in terms of the CIP components including the allocation of target districts. -

95 Status of Brucellosis in Dairy Cattle of Kapilvastu

Nepalese Vet J. 34: 95-100 STATUS OF BRUCELLOSIS IN DAIRY CATTLE OF KAPILVASTU AND BHAKTAPUR DISTRICTS OF NEPAL B. Ghimire1, S. Thapa Chhetri2 and D. R. Khanal3* 1Asia Network for Sustainable Agriculture Bioresources (ANSAB), Kathmandu 2Agriculture and Forestry University, Rampur, Chitwan 3Animal Health Research Division, Nepal Agricultural Research Council, Lalitpur (*email: [email protected]) ABSTRACT Brucellosis is a zoonotic disease that causes abortion in dairy cattle. To find out its status, serological tests were conducted, during June-July 2013, in 48 sera samples from dairy cattle (23 from Kapilvastu and 25 from Bhaktapur districts) having the recent history of abortion. Out of 48 samples 6 (12.5%) were positive on Rose Bengal Plate Test. Among 6 positive samples, 2 (8.69%) were from Kapilvastu and 4 (16%) from Bhakhtapur. Considering the positive cases of brucellosis in the dairy pocket areas and its threat of transmission to other animals and human, a suitable preventive and control measures including the regular test and segregation of sero-positive animals, effective quarantine, legislative measures and awareness programs for farmers, veterinarian, technicians and stakeholders are recommended. Keywords: abortion, brucella, cattle, rose bengal plate test, zoonosis INTRODUCTION Brucellosis is one of the most widespread bacterial zoonotic diseases of cattle, buffalo, swine, goats, sheep, dogs and human, resulting into tremendous economic losses in endemic regions. In human, it causes Malta or Mediterranean fever (Godfroid et al., 2005). It is caused by gram- negative coccobacilli of the genus Brucella that contains a group of very closely related bacteria. The first member of the group, Brucella melitensis, affects primarily sheep and goats. -

ZSL National Red List of Nepal's Birds Volume 5

The Status of Nepal's Birds: The National Red List Series Volume 5 Published by: The Zoological Society of London, Regent’s Park, London, NW1 4RY, UK Copyright: ©Zoological Society of London and Contributors 2016. All Rights reserved. The use and reproduction of any part of this publication is welcomed for non-commercial purposes only, provided that the source is acknowledged. ISBN: 978-0-900881-75-6 Citation: Inskipp C., Baral H. S., Phuyal S., Bhatt T. R., Khatiwada M., Inskipp, T, Khatiwada A., Gurung S., Singh P. B., Murray L., Poudyal L. and Amin R. (2016) The status of Nepal's Birds: The national red list series. Zoological Society of London, UK. Keywords: Nepal, biodiversity, threatened species, conservation, birds, Red List. Front Cover Back Cover Otus bakkamoena Aceros nipalensis A pair of Collared Scops Owls; owls are A pair of Rufous-necked Hornbills; species highly threatened especially by persecution Hodgson first described for science Raj Man Singh / Brian Hodgson and sadly now extinct in Nepal. Raj Man Singh / Brian Hodgson The designation of geographical entities in this book, and the presentation of the material, do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of participating organizations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, or area, or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect those of any participating organizations. Notes on front and back cover design: The watercolours reproduced on the covers and within this book are taken from the notebooks of Brian Houghton Hodgson (1800-1894). -

An Assessment of School Deworming Program in Surkhet and Kailali District

2010 AN ASSESSMENT OF SCHOOL DEWORMING PROGRAM IN SURKHET AND KAILALI DISTRICT 2010 Nepal Health Research Council Acknowledgement I am grateful to all the members of steering committee of Nutrition unit of Nepal Health Research Council (NHRC) for their efforts and commitment for the completion of this report. I am greatly indebted to Dr. Laxmi Raj Pathak, Dr. Baburam Marasini and Mr. Rajkumar Pokharel for their invaluable advice in this project. I would like to give thanks to Dr. Shanker Pratap Singh, Member Secretary for his kind contribution in this study. I express my special thanks to core research team, Dr. Gajananda Prakash Bhandari, Senior Epidemiologist, Ms. Femila Sapkota, Research Officer, Ms. Chandika Shrestha Assistant Research Officer and Ms. Kritika Paudel, Senior Research Assistant of Nepal Health Research Council for their great effort in proposal development, data collection, and data analysis and further more in completion of research project. I extend my sincere thanks to the D(P)HO and DEO office of Surkhet and Kailali district. Similarly, I am very pleased to acknowledge all the school teachers, parents and health institution incharge of the selected schools and health institution who helped by providing the valuable data and information without which the research could not have been accomplished. I am highly indebted to resource person and school inspector of DEO Surkhet and Kailali for their help during data collection. Similarly, special thanks go to BaSE office, Kailali for the valuable information. I express thanks to all the enumerators for their endless labor and hard working during data collection. Lastly, I am grateful to all those direct and indirect hands for help and support in successful completion of the study. -

The Nepal Smallholder Irrigation Market Initiative (SIMI) WINROCK/IDE/CEAPRED/SAPPROS

Increasing Rural Income through Micro Irrigation & Market Integration The Nepal Smallholder Irrigation Market Initiative (SIMI) WINROCK/IDE/CEAPRED/SAPPROS USAID Cooperative Agreement No. 367-A-00-03-00116-00 Nepal SIMI Annual (Fourth Quarter) Performance Report 2005 July 1, 2004 – June 30, 2005 (F.Y. 2004/5) Nepal SIMI Performance Report No. 8 Mailing Address GPO 8975, EPC 2560, Bakhundol, Lalitpur Tel: (977-1) 5535565 Fax: 5520846 E-mail: [email protected] Table of Contents 1.0 Background…………………………………………………………………………..1 1.1 SIMI goals………………………………………………………………………...2 1.2 Partners…………………………………………………………………………...2 2.0 Expected Results (Output or Indicators)……...……………………………………3 3.0 SIMI Indicator Target Performance………..……………………………….……..3 3.1 Activities………………………………………………………………………..5 3.1.1 Program Mobilization…………………………………………………5 3.1.2 Supply Chain Development……………………………………………5 3.1.3 Social Marketing……………………………………………………….7 3.1.4 Market Development…………………………………………………..7 3.1.5 Collaborative Partnerships and Linkages with Government……….8 3.1.6 Water Source Development…………………………………………...8 3.1.7 Gender Program……………………………………………………….8 3.1.8 Monitoring and Evaluation……………………………………………9 3.1.9 Success Stories………………………………………………………...10 3.1.10 Component wise Highlighted Program……………………………...18 3.2 Activities Planned for the Next Three Months……………………………...30 4.0 Statement of Work………………………………………………………………….31 5.0 Administrative Information………………………………………………………..31 6.0 Financial Information………………………………………………………………33 Annex A Nepal SIMI Project Areas…………………………………………………...34 -

TSLC PMT Result

Page 62 of 132 Rank Token No SLC/SEE Reg No Name District Palika WardNo Father Mother Village PMTScore Gender TSLC 1 42060 7574O15075 SOBHA BOHARA BOHARA Darchula Rithachaupata 3 HARI SINGH BOHARA BIMA BOHARA AMKUR 890.1 Female 2 39231 7569013048 Sanju Singh Bajura Gotree 9 Gyanendra Singh Jansara Singh Manikanda 902.7 Male 3 40574 7559004049 LOGAJAN BHANDARI Humla ShreeNagar 1 Hari Bhandari Amani Bhandari Bhandari gau 907 Male 4 40374 6560016016 DHANRAJ TAMATA Mugu Dhainakot 8 Bali Tamata Puni kala Tamata Dalitbada 908.2 Male 5 36515 7569004014 BHUVAN BAHADUR BK Bajura Martadi 3 Karna bahadur bk Dhauli lawar Chaurata 908.5 Male 6 43877 6960005019 NANDA SINGH B K Mugu Kotdanda 9 Jaya bahadur tiruwa Muga tiruwa Luee kotdanda mugu 910.4 Male 7 40945 7535076072 Saroj raut kurmi Rautahat GarudaBairiya 7 biswanath raut pramila devi pipariya dostiya 911.3 Male 8 42712 7569023079 NISHA BUDHa Bajura Sappata 6 GAN BAHADUR BUDHA AABHARI BUDHA CHUDARI 911.4 Female 9 35970 7260012119 RAMU TAMATATA Mugu Seri 5 Padam Bahadur Tamata Manamata Tamata Bamkanda 912.6 Female 10 36673 7375025003 Akbar Od Baitadi Pancheswor 3 Ganesh ram od Kalawati od Kalauti 915.4 Male 11 40529 7335011133 PRAMOD KUMAR PANDIT Rautahat Dharhari 5 MISHRI PANDIT URMILA DEVI 915.8 Male 12 42683 7525055002 BIMALA RAI Nuwakot Madanpur 4 Man Bahadur Rai Gauri Maya Rai Ghodghad 915.9 Female 13 42758 7525055016 SABIN AALE MAGAR Nuwakot Madanpur 4 Raj Kumar Aale Magqar Devi Aale Magar Ghodghad 915.9 Male 14 42459 7217094014 SOBHA DHAKAL Dolakha GhangSukathokar 2 Bishnu Prasad Dhakal -

Displacemect of People from Terai District

KAPILBASTU DISTRICT: REPORTED DISPLACEMENT - as of 5 November, 2007 82°30'0"E 82°37'30"E 82°45'0"E 82°52'30"E 83°0'0"E 83°7'30"E Maidan Juluke Siddhara Arghakhanchi Bela Thada Simalapani Gangapraspur Gadhawa Gobardiya D a n g 27°45'0"N Map Locator 050 100 200 300 Dubiya Kilometers 204 IDPs (32 families) at Ghumchir, 27°45'0"N Shivagadhi BagargangaVDC Saljhundi Malwar Shivapur Motipur Koilabas Mahendrakot Barakulpur Banganga Gugauli 992+ IDPs at Shankarpur, Shivagadhi VDC 400 IDPs (80 families) at Chunna, Barakulpur VDC Gajehada Budhi Kopawa Rudrapur Jayanagar Chanai Hariharpur Birpur Kapilbastu Hathausa 27°37'30"N Nigalihawa Thunhiya Patna 27°37'30"N Rajpur Khurhuriya Manpur Patthardaihiya Bishunpur Lalpur Mahuwa Jahadi Jawabhari Balaramwapur Dhankauli Tilaurakot Patariya Udayapur Fulika Sadi Administrative Boundaries Ganeshpur Rupandehi Baraipur Ramnagar Maharajganj Bhalubari District Bahadurganj KapilbastuN.P.Infrustructure Damage by VDC Bhagwanpur VidhyaNagar (based on DSP data as of 26 Oct. 2007) $+ Dharmpaniya Nandanagar VDC 140 Sauraha Taulihawa Pakadi Major Roads Ajigara 120 Sisawa120 Dohani Shipanagar Dumara Highway Sirsihawa Kajarhawa Baskhaur Purusottampur 96 Kushhawa 100 Feeder Road KrishnaNagar Milmi Labani Singhkhor Gotihawa Gauri Basantapur Masina 27°30'0"N District Road 80 Haranampur74 71 n n 27°30'0"N o 64 Abhirawa o i Harduona i t t Other Road c 60 c Bithuwa e e r Parsohiya r i i Somdiha Baluhawa District HQ D Bedauli Titirkhi $+ D 37 t t 40 n n Bijuwa Most affected VDCs based on Killings/household destroyed e e m m 18 e Pipra e 20 Rangapur15 Hathihawa v v 12 Municipalities o o 7 2 3 M M 2 Water bodies 0 The majority of displaced in India have reportedly Barakulpur Birpur Bishunpur Ganeshpur Khurhuriya KrishnaNagar Motipur Patthardaihiya IDP Concentrations Sum of House destroyed Sum of House partial damage / looted Sum of huts burned returned to Nepal, however organisations estimate 400+ Sum of Shops destroyed Sum of Hotels Sum of Petrol pumps remain with host families / relatives.