Tri Hita Karana, Sacred Artistic Practices, and Musical Ecology in Bali

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Glossary.Herbst.Bali.1928.Kebyar

Bali 1928 – Volume I – Gamelan Gong Kebyar Music from Belaluan, Pangkung, Busungbiu by Edward Herbst Glossary of Balinese Musical Terms Glossary angklung Four–tone gamelan most often associated with cremation rituals but also used for a wide range of ceremonies and to accompany dance. angsel Instrumental and dance phrasing break; climax, cadence. arja Dance opera dating from the turn of the 20th century and growing out of a combination of gambuh dance–drama and pupuh (sekar alit; tembang macapat) songs; accompanied by gamelan gaguntangan with suling ‘bamboo flute’, bamboo guntang in place of gong or kempur, and small kendang ‘drums’. babarongan Gamelan associated with barong dance–drama and Calonarang; close relative of palégongan. bapang Gong cycle or meter with 8 or 16 beats per gong (or kempur) phrased (G).P.t.P.G baris Martial dance performed by groups of men in ritual contexts; developed into a narrative dance–drama (baris melampahan) in the early 20th century and a solo tari lepas performed by boys or young men during the same period. barungan gdé Literally ‘large set of instruments’, but in fact referring to the expanded number of gangsa keys and réyong replacing trompong in gamelan gong kuna and kebyar. batél Cycle or meter with two ketukan beats (the most basic pulse) for each kempur or gong; the shortest of all phrase units. bilah Bronze, iron or bamboo key of a gamelan instrument. byar Root of ‘kebyar’; onomatopoetic term meaning krébék, both ‘thunderclap’ and ‘flash of lightning’ in Balinese, or kilat (Indonesian for ‘lightning’); also a sonority created by full gamelan sounding on the same scale tone (with secondary tones from the réyong); See p. -

Balinese Dances As a Means of Tourist Attraction

BALINESE DANCES AS A MEANS OF TOURIST ATTRACTION : AN ECONOMIC PERSPECTIVE By : Lie Liana Dosen Tetap Fakultas Teknologi Informasi Universitas Stikubank Semarang ABSTRACT Makalah ini menguraikan secara ringkas Tari Bali yang ditinjau dari perspekif ekonomi dengan memanfaatkan Bali yang terkenal sebagai salah satu daerah tujuan wisata di Indonesia. Keterkenalan Bali merupakan keuntungan tersendiri bagi pelaku bisnis khususnya bisnis pariwisata. Kedatangan wisatawan asing dengan membawa dolar telah meningkatkan ekonomi masyarakat Bali, yang berarti pula devisa bagi Indonesia. Bali terkenal karena kekayaannya dalam bidang kesenian, khususnya seni tari. Tari Bali lebih disukai karena lebih glamor, ekspresif dan dinamis. Oleh karena itu seni tari yang telah ada harus dilestarikan dan dikembangkan agar tidak punah, terutama dari perspektif ekonomi. Tari Bali terbukti memiliki nilai ekonomi yang tinggi terutama karena bisa ‘go international’ dan tentunya dapat meningkatkan pemasukan devisa negara melalui sektor pariwisata. Kata Kunci: Tari, ekonomi, pariwisata, A. INTRODUCTION It is commonly known that Bali is the largest foreign and domestic tourist destination in Indonesia and is renowned for its highly developed arts, including dances, sculptures, paintings, leather works, traditional music and metalworking. Meanwhile, in terms of history, Bali has been inhabited since early prehistoric times firstly by descendants of a prehistoric race who migrated through Asia mainland to the Indonesian archipelago, thought to have first settled in Bali around 3000 BC. Stone tools dating from this time have been found near the village of Cekik in the island's west. Most importantly, Balinese culture was strongly influenced by Indian, and particularly Sanskrit, culture, in a process beginning around the 1st century AD. The name Balidwipa has been discovered from various inscriptions. -

Cultural Landscape of Bali Province (Indonesia) No 1194Rev

International Assistance from the World Heritage Fund for preparing the Nomination Cultural Landscape of Bali Province 30 June 2001 (Indonesia) Date received by the World Heritage Centre No 1194rev 31 January 2007 28 January 2011 Background This is a deferred nomination (32 COM, Quebec City, Official name as proposed by the State Party 2008). The Cultural Landscape of Bali Province: the Subak System as a Manifestation of the Tri Hita Karana The World Heritage Committee adopted the following Philosophy decision (Decision 32 COM 8B.22): Location The World Heritage Committee, Province of Bali 1. Having examined Documents WHC-08/32.COM/8B Indonesia and WHC-08/32.COM/INF.8B1, 2. Defers the examination of the nomination of the Brief description Cultural Landscape of Bali Province, Indonesia, to the Five sites of rice terraces and associated water temples World Heritage List in order to allow the State Party to: on the island of Bali represent the subak system, a a) reconsider the choice of sites to allow a unique social and religious democratic institution of self- nomination on the cultural landscape of Bali that governing associations of farmers who share reflects the extent and scope of the subak system of responsibility for the just and efficient use of irrigation water management and the profound effect it has water needed to cultivate terraced paddy rice fields. had on the cultural landscape and political, social and agricultural systems of land management over at The success of the thousand year old subak system, least a millennia; based on weirs to divert water from rivers flowing from b) consider re-nominating a site or sites that display volcanic lakes through irrigation tunnels onto rice the close link between rice terraces, water temples, terraces carved out of the flanks of mountains, has villages and forest catchment areas and where the created a landscape perceived to be of great beauty and traditional subak system is still functioning in its one that is ecologically sustainable. -

The Islamic Traditions of Cirebon

the islamic traditions of cirebon Ibadat and adat among javanese muslims A. G. Muhaimin Department of Anthropology Division of Society and Environment Research School of Pacific and Asian Studies July 1995 Published by ANU E Press The Australian National University Canberra ACT 0200, Australia Email: [email protected] Web: http://epress.anu.edu.au National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Muhaimin, Abdul Ghoffir. The Islamic traditions of Cirebon : ibadat and adat among Javanese muslims. Bibliography. ISBN 1 920942 30 0 (pbk.) ISBN 1 920942 31 9 (online) 1. Islam - Indonesia - Cirebon - Rituals. 2. Muslims - Indonesia - Cirebon. 3. Rites and ceremonies - Indonesia - Cirebon. I. Title. 297.5095982 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. Cover design by Teresa Prowse Printed by University Printing Services, ANU This edition © 2006 ANU E Press the islamic traditions of cirebon Ibadat and adat among javanese muslims Islam in Southeast Asia Series Theses at The Australian National University are assessed by external examiners and students are expected to take into account the advice of their examiners before they submit to the University Library the final versions of their theses. For this series, this final version of the thesis has been used as the basis for publication, taking into account other changes that the author may have decided to undertake. In some cases, a few minor editorial revisions have made to the work. The acknowledgements in each of these publications provide information on the supervisors of the thesis and those who contributed to its development. -

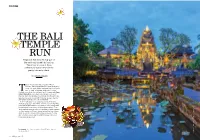

THE BALI TEMPLE RUN Temples in Bali Share the Top Spot on the Must-Visit List with Its Beaches

CULTURE THE BALI TEMPLE RUN Temples in Bali share the top spot on the must-visit list with its beaches. Take a look at some of these architectural marvels that dot the pretty Indonesian island. TEXT ANURAG MALLICK he sun was about to set across the cliffs of Uluwatu, the stony headland that gave the place its name. Our guide, Made, explained that ulu is ‘land’s end’ or ‘head’ in Balinese, while watu is ‘stone’. PerchedT on a rock at the southwest tip of the peninsula, Pura Luhur Uluwatu is a pura segara (sea temple) and one of the nine directional temples of Bali protecting the island. We gaped at the waves crashing 230 ft below, unaware that the real spectacle was about to unfold elsewhere. A short walk led us to an amphitheatre overlooking the dramatic seascape. In the middle, around a sacred lamp, fifty bare-chested performers sat in concentric rings, unperturbed by the hushed conversations of the packed audience. They sat in meditative repose, with cool sandalwood paste smeared on their temples and flowers tucked behind their ears. Sharp at six, chants of cak ke-cak stirred the evening air. For the next one hour, we sat open-mouthed in awe at Bali’s most fascinating temple ritual. Facing page: Pura Taman Saraswati is a beautiful water temple in the heart of Ubud. Elena Ermakova / Shutterstock.com; All illustrations: Shutterstock.com All illustrations: / Shutterstock.com; Elena Ermakova 102 JetWings April 2017 JetWings April 2017 103 CULTURE The Kecak dance, filmed in movies such as There are four main types of temples in Bali – public Samsara and Tarsem Singh’s The Fall, was an temples, village temples, family temples for ancestor worship, animated retelling of the popular Hindu epic and functional temples based on profession. -

Introduction

Cambridge University Press 0521624444 - Varieties of Javanese Religion: An Anthropological Account Andrew Beatty Excerpt More information 1 Introduction This book is about religion in Java ± its diverse forms, controversies, and reconciliations; more abstractly it is about cultural difference and syncretism. At a time when anthropology is increasingly preoccupied with cultural pluralism in the West, and with the challenges to personal identity, mutual tolerance, and social harmony that it presents, the example of Java reminds us that some of the more `traditional' societies have been dealing with similar problems for quite some time. The varieties of Javanese religion are, of course, well known, thanks to a number of excellent studies. In what follows, however, my chief interest is in the effect of diversity upon Javanese religion. In looking at the mutual in¯uences of Islamic piety, mysticism, Hinduism, and folk tradition upon each other, and at their different compromises with the fact of diversity, I hope to give a credible and dynamic account of how religion works in a complex society. The setting for this book ± Banyuwangi in the easternmost part of Java ± is particularly appropriate to such an enterprise. In the standard viewof things, the various forms of Javanese religion are unevenly distributed among village, market, court/palace, and town. Although most communities contain orthodox Muslims as well as practitioners of other tendencies (Koentjaraningrat 1985: 318), a rough spatial separa- tion along religious and cultural lines (or a polarization within the most heterogeneous villages) has, allegedly, been characteristic of Java from the early years of the century (Jay 1963), though the sharpness of divisions has ¯uctuated with political developments. -

Santosh-Francis Scale of Attitude Toward Hinduism

University of Warwick institutional repository: http://go.warwick.ac.uk/wrap This paper is made available online in accordance with publisher policies. Please scroll down to view the document itself. Please refer to the repository record for this item and our policy information available from the repository home page for further information. To see the final version of this paper please visit the publisher’s website. Access to the published version may require a subscription. Author(s): C. B. J. Lesmana, Niko Tiliopoulos and Leslie J. Francis Article Title: The Internal Consistency Reliability of the Santosh-Francis Scale of Attitude toward Hinduism among Balinese Hindus Year of publication: 2011 Link to published article: http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1007/s11407-011-9108-5 Publisher statement: The original publication is available at www.springerlink.com Running head: SANTOSH-FRANCIS SCALE OF ATTITUDE TOWARD HINDUISM 1 The internal consistency reliability of the Santosh-Francis Scale of Attitude toward Hinduism among Balinese Hindus C. B. J. Lesmana Udayana University, Denpasar, Indonesia Niko Tiliopoulos The University of Sydney, Australia Leslie J. Francis* The University of Warwick, UK Author note: *Corresponding author: Leslie J Francis Warwick Religions & Education Research Unit Institute of Education The University of Warwick Coventry CV4 7AL United Kingdom Tel: +44 (0)24 7652 2539 Fax: +44 (0)24 7657 2638 Email: [email protected] C:\Users\Leslie\Desktop\Sandy Hughes\Articles\Tiliopoulos\S-F Scale Balinese Hindus.doc 02/02/2012 SANTOSH-FRANCIS ATTITUDE TOWARD BALINESE HINDUS 2 Abstract The present paper intends to make a contribution to the empirical psychology of religion among Hindus. -

Term-List-For-Ch4-Asian-Theatre-2

Asian Theatre: India, China, Korea, Japan, Indonesia, & Cambodia Cultural Periods and Events Theatrical Developments Persons Aryan migration & caste system Natya-Shastra (rasas & the Bharata Muni & Abhinavagupta Vedic & Gandhara Periods spectator’s liberation) Shūdraka & Kalidasa Hinduism & Sanskrit texts Islamic invasions actor-manager (sudtradhara) Buddhism (promising what?) shamanic rituals jester (vidushaka) Hellenistic influence court entertainments with string-puller (sudtradhara) Classical Period & Ashoka Jester Ming sheng, dan, jing, & chou (meanings) Theravada & Mahayana wrestling & Baixi men & women who played across gender Gupta golden age impersonations, dances, & women who led troupes Medieval Period acrobatics, sword tricks Guan Hanqing Muslim invasions small plays of song and dance Tang Xianzu Chola Dynasty Pear Garden & adjutant Li Yu Early Modern Period plays Kan’ami & Zeami Mughal Empire red light districts with shite & shite-tsure (across gender), waki, Colonial Period with British East southern dramas & waki-tsure, & kyogen India Company variety show musicals chorus of 8 men, musicians, & onstage British Raj with one star singing per stagehand (kuroko) Dramatic Performances Act act Okuni Contemporary Period complex, poetic dramas onnagata Shang, Zhou, Qin, Han, Jin, kun operas with plaintive Chikamatsu Northern & Southern, Sui, Tang, music & flowing Danjuro I Song, Yuan, Ming, & Qing melodies/dancing chanter, 3 puppeteers per puppet, & Dynasties Beijing Opera (jingju) as shamisen player nationalist & communist rulers -

Bonnie Simoa, Dance

Applicant For Paid Sabbatical Application Information Name: Bonnie Simoa Department/Division: Dance/Arts Ext.: 5645 Email address: [email protected] FTE: 1.0 Home Phone: 541.292.4417 Years at Lane under contract: 17 (Since Fall 1999) Previous paid sabbatical leave dates (if applicable): 2 # of terms of paid sabbatical leave awarded in the past: 2 Sabbatical Project Title: Intangible Cultural Heritage: Legong and Beyond Term(s) requested for leave: Spring Leave Location(s): Bali, Indonesia Applicant Statement: I have read the guidelines and criteria for sabbatical leave, and I understand them. If accepted, I agree to complete the sabbatical project as described in my application as well as the written and oral reports. I understand that I will not be granted a sabbatical in the future if I do not follow these guidelines and complete the oral and written reports. (The committee recognizes that there may be minor changes to the timeline and your proposed plan.) Applicant signature: Bonnie Simoa Date: 2/1/16 1 Bonnie Simoa Sabbatical Application 2017 Intangible Cultural Heritage: Legong and Beyond 1. INTENT and PLAN This sabbatical proposal consists of travel to Bali, Indonesia to build on my knowledge and understanding of traditional Balinese dance. While my previous sabbatical in 2010 focused primarily on the embodiment and execution of the rare Legong Keraton Playon, this research focuses on the contextual placement of the dance in relation to its roots, the costume as a tool for transcendence, and the related Sanghyang Dedari trance-dance. The 200 year-old Legong Keraton Playon has been the focus of my research, for which I have gained international recognition. -

The Origins of Balinese Legong

STEPHEN DAVIES The origins of Balinese legong Introduction In this paper I discuss the origin of the Balinese dance genre of legong. I date this from the late nineteenth century, with the dance achieving its definitive form in the period 1916-1932. These conclusions are at odds with the most common history told for legong, according to which it first appeared in the earliest years of the nineteenth century. The genre Legong is a secular (balih-balihan) Balinese dance genre.1 Though originally as- sociated with the palace,2 legong has long been performed in villages, espe- cially at temple ceremonies, as well as at Balinese festivals of the arts. Since the 1920s, abridged versions of legong dances have featured in concerts organized for tourists and in overseas tours by Balinese orchestras. Indeed, the dance has become culturally emblematic, and its image is used to advertise Bali to the world. Traditionally, the dancers are three young girls; the servant (condong), who dances a prelude, and two legong. All wear elaborate costumes of gilded cloth with ornate accessories and frangipani-crowned headdresses.3 The core 1 Proyek pemeliharaan 1971. Like all Balinese dances, legong is an offering to the gods. It is ‘secu- lar’ in that it is not one of the dance forms permitted in the inner yards of the temple. Though it is performed at temple ceremonies, the performance takes place immediately outside the temple, as is also the case with many of the other entertainments. The controversial three-part classification adopted in 1971 was motivated by a desire to prevent the commercialization of ritual dances as tourist fare. -

JURNAL SIMBOLIKA Ritualisasi Kesenian Barong Dalam Estetika

Jurnal Simbolika: Research and Learning in Comunication Study 6(1) April 2020 ISSN 2442-9198 (Print) ISSN 2442-9996 (Online) JURNAL SIMBOLIKA Research and Learning in Comunication Study Available online http://ojs.uma.ac.id/index.php/simbolika DOI: https://doi.org/10.31289/simbollika.v6i1.3240 Ritualisasi Kesenian Barong dalam Estetika Budaya: Studi Eksploratif Komunikasi Intra Personal Masyarakat Kota Beribadat Ritualization’s Art of Barong in Aesthetic Culture: Explorative Study of Intra Personal Communication as a City Worship Community Tika Ristia Djaya Program Studi Ilmu Komunikasi, Fakultas Ilmu Sosial dan Ilmu Politik, Universitas Selamat Sri, Kendal, Jawa Tengah, Indonesia Diterima:22 Desember 2019; Disetujui: 19 April 2020; Dipublish: 27 April 2020 Abstrak Tujuan dari penelitian ini adalah untuk mengetahui cara pemain barong melakukan ritual, tanggapan masyarakat terhadap ritual yang dilakukan oleh para pemain barong dan pengaruh ritual terhadap perilaku personal pemain barong Singo Kencono di Kendal Jawa Tengah. Penelitian ini menggunakan metode kualitatif dengan pendekatan eksploratif. Hasil dari penelitian menunjukkan bahwa ritual yang dilakukan pemain barong diantaranya adalah lek-lekan di malam hari sebelum pementasan dan disertai dengan pengajian, menggunakan sesaji semacam jajan pasar, pisang, bunga dan telor. Masyarakat modern memaknai sesaji tersebut sebagai seni dalam budaya, bukan aliran kepercayaan yang dipercayai sebagai pedoman kepercayaan kehidupannya. Ritual tidak menyebabkan pengaruh negatif pada pemain barong tetapi justru meningkatkan ketaqwaan terhadap Tuhan Yang Maha Esa. Kesenian barong Singo Kencono dibentuk guna nguri-uri budaya meskipun sudah banyak perubahan sesuai dengan perkembangan jaman tetapi tetap tidak menghilangkan budaya asli, selain itu kesenian barong Singo Kencono ini dibentuk dan dimainkan untuk menghibur masyarakat. -

04 Days Bali Exploration

Booth no: 7H12 NATAS offer -200/- Per couple Tour Code: E3N-DPS Incredible Odyssey 04 Days Bali exploration Bali: Indonesia’s most famous island, is located to the west of Java in the Lesser Sunda Islands. It is world-renowned for its scenic rice terraces, fragrant cuisine, stunning beaches and a galore of culture and tradition. With its elaborate temples, endless coastline, some of the world's best coral reefs, waterfalls and retreats, Bali combines leisure and adventure, spiritual awakening and hard-partying all into one island that people from all over the world come to lose themselves in. The island boasts some of the best sunsets and sunrises, enough to captivate and entice you into never leaving this place. Home to the coral reefs of Tulamben, the mountain peaks of Kintamani, the beaches and scenic routes of Seminyak and Kuta, with ancient temples and traditional village life of Ubud, Bali's charm is boundless, as are its opportunities for fun. I T I N E R A R Y Day 01: ARRIVE BALI INTERNATIONAL FLIGHT + SUN SET TOUR D Arrive Bali airport and met by your English-speaking driver. Meet & greet and transfer to your land transport to reach your hotel for freshening up. Depending upon the landing time of your flight, we may proceed directly to Uluwatu for the majestic Sun set. Visit the Uluwatu temple or known as the rock cliff temple in the southern Bali islands. You will admire the beautiful view of sunset view and the Indian ocean. Further we will enjoy and be apart of the dance performance of Kecak dance near the temple.