Ariel 35(3-4)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

AE Newsletter 2020

Colonel Shorty Powers Composite Squadron July 25, 2020 AEROSPACE Aircraft | Spacecraft | Biography | Squadron Gen. Ira C. Eaker A New Eagle Boeing to build new F-15EXs for USAF The Department of the Air Force and Boeing recently signed a deal worth 1.2 billion dollars for the first lot of eight F-15EX jets that will be delivered to Eglin Air Force Base, Florida. The aircraft will replace the oldest F-15Cs and F-15Ds in the U.S. Air Force fleet. The first two already built F-15EX aircraft will be delivered during the second quarter of 2021, while the remaining aircraft will be delivered in 2023. The Air Force plans to buy 76 F-15EX aircraft. The new F-15EX was developed to meet needs identified by the National Defense Strategy review which directed the U.S. armed services to adapt to the new threats from China and Russia. The most burdensome requirement is the need for the Air Force to add 74 new squadrons to the existing 312 squadrons by 2030. The General Ira C. Eaker was one of the forefathers of an independent Air Force. With General (then major) Spaatz, in 1929 Eaker remained aloft aboard The Question Mark, a modified Atlantic-Fokker C-2A, for nearly a week, to demonstrate a newfound capability of aerial refueling. During WWII, Eaker rose to the grade of lieutenant general and commanded the Eighth Air Force, "The Mighty Eighth" force of strategic The first F-15EX being assembled at Boeing facilities. (Photo: Boeing) Aerospace Newsletter 1 Colonel Shorty Powers Composite Squadron July 25, 2020 Eaker (continued) Air Force also seeks to lower the average aircraft age of 28 years down to 15 years without losing any capacity. -

Ulysses Awardees

Ulysses Awardees Irish Higher Project Leader - Project Leader - French Higher Funding Education Disciplinary Area Project Title Ireland France Education Institution Institution Comparing Laws with Help from Humanities including Peter Arnds IRC / Embassy TCD Renaud Colson ENSCM, Montpellier the Humanities: Translation Theory languages, Law to the Rescue of Legal Studies Novel biomarkers of interplay between neuroglobin and George Barreto HRB / Embassy UL Karim Belarbi Université de Nantes Life Sciences neuroinflammation in Parkinson’s disease Geometric Constructions of Codes Eimear Byrne IRC / Embassy UCD Martino Borello University of Lille Mathematics for Secret Sharing Schemes BOUHÉREAU: EXILE, TOLERATION Didier Poton de Humanities including Derval Conroy IRC / Embassy UCD University Paris 8 - LAGA AND CARE IN THE EARLY MODERN Xaintrailles languages PERIOD Knotting peptides for DNA Fabian Cougnon IRC / Embassy NUIG Sebastian Ulrich La Rochelle University Chemistry recognition and gene delivery Automating Segmentation and Computer Science & Kathleen Curran HRB / Embassy UCD David Bendahan Muscle Architecture Analysis from Telecommunications Aix Marseille University Diffusion Tensor Imaging The Impact of Student Exchanges Social science and Ronald Davies IRC / Embassy UCD Farid Toubal on International Trade: The Role of University of Paris- economics Cultural Similarity Dauphine -- PSL Computer Science & Three dimensional audio and Gordon Delap IRC / Embassy MU Thibaud Keller Telecommunications musical experimentation CNRS – LaBRI Multi-scale, -

Let's Go to a Comet!

Mission Rosetta Let’s go to a comet! Elsa Montagnon European Space Agency 1 What is left to explore today? 15th century Credits: ESA/AOES Medialab 21st century 2 Back to the origins… 3 What has happened since the big bang? Big bang 13 billion years ago ejects hydrogen and helium From elements to dust From water to heavy elements From dust to gas From solar cloud to the solar system: planets, asteroids, comets 4 How do we see the solar system today? Galactic Tides Nearby Stars Large Clouds LPidCtLong Period Comets Short Period Comets Galactic Tides Inner Outer Oort Oort Pluto Cloud Cloud ? Stable Stable Kuiper Belt 10 Gy 1 Gy ? 10 50 100 Alpha I, e 1000 Centauri 10^4 Ejected AU 10^5 3.10^5 5 Where are we going? Comet 67P / Churyumow-Gerasimenko 3-D reconstruction of nucleus based on 12 March, 2003 Hubble Space Telescope observations Nucleus diameter: 4km Discovered in 1969 Orbital period: 6.6 years Pole End Side Nasa, Esa and Philippe Lamy (Laboratoire d’Astrobomie Spatiale) - STScl-PRC03-26 6 A picture of the comet… Credits: ESA and European Southern Observatory 7 The Mission Rendezvous with the comet shortly after aphelion Follow the comet up to perihelion and beyond Deploy a lander on the comet surface QuickTime™ and a YUV420 codec decompressor are needed to see this picture. 8 The Journey Launch: March 2004 Launcher: Ariane 5 Rendezvous with comet: August 2014 Distance: 6.5 billions km Cruise duration: 10 years Mission duration: 2 years 9 The Cruise The comet is very far away. -

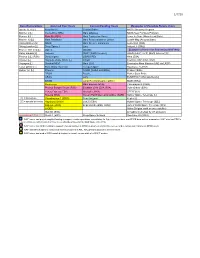

List of Missions Using SPICE (PDF)

1/7/20 Data Restorations Selected Past Users Current/Pending Users Examples of Possible Future Users Apollo 15, 16 [L] Magellan [L] Cassini Orbiter NASA Discovery Program Mariner 2 [L] Clementine (NRL) Mars Odyssey NASA New Frontiers Program Mariner 9 [L] Mars 96 (RSA) Mars Exploration Rover Lunar IceCube (Moorehead State) Mariner 10 [L] Mars Pathfinder Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter LunaH-Map (Arizona State) Viking Orbiters [L] NEAR Mars Science Laboratory Luna-Glob (RSA) Viking Landers [L] Deep Space 1 Juno Aditya-L1 (ISRO) Pioneer 10/11/12 [L] Galileo MAVEN Examples of Users not Requesting NAIF Help Haley armada [L] Genesis SMAP (Earth Science) GOLD (LASP, UCF) (Earth Science) [L] Phobos 2 [L] (RSA) Deep Impact OSIRIS REx Hera (ESA) Ulysses [L] Huygens Probe (ESA) [L] InSight ExoMars RSP (ESA, RSA) Voyagers [L] Stardust/NExT Mars 2020 Emmirates Mars Mission (UAE via LASP) Lunar Orbiter [L] Mars Global Surveyor Europa Clipper Hayabusa-2 (JAXA) Helios 1,2 [L] Phoenix NISAR (NASA and ISRO) Proba-3 (ESA) EPOXI Psyche Parker Solar Probe GRAIL Lucy EUMETSAT GEO satellites [L] DAWN Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter MOM (ISRO) Messenger Mars Express (ESA) Chandrayan-2 (ISRO) Phobos Sample Return (RSA) ExoMars 2016 (ESA, RSA) Solar Orbiter (ESA) Venus Express (ESA) Akatsuki (JAXA) STEREO [L] Rosetta (ESA) Korean Pathfinder Lunar Orbiter (KARI) Spitzer Space Telescope [L] [L] = limited use Chandrayaan-1 (ISRO) New Horizons Kepler [L] [S] = special services Hayabusa (JAXA) JUICE (ESA) Hubble Space Telescope [S][L] Kaguya (JAXA) Bepicolombo (ESA, JAXA) James Webb Space Telescope [S][L] LADEE Altius (Belgian earth science satellite) ISO [S] (ESA) Armadillo (CubeSat, by UT at Austin) Last updated: 1/7/20 Smart-1 (ESA) Deep Space Network Spectrum-RG (RSA) NAIF has or had project-supplied funding to support mission operations, consultation for flight team members, and SPICE data archive preparation. -

Solar Orbiter Assessment Study and Model Payload

Solar Orbiter assessment study and model payload N.Rando(1), L.Gerlach(2), G.Janin(4), B.Johlander(1), A.Jeanes(1), A.Lyngvi(1), R.Marsden(3), A.Owens(1), U.Telljohann(1), D.Lumb(1) and T.Peacock(1). (1) Science Payload & Advanced Concepts Office, (2) Electrical Engineering Department, (3) Research and Scientific Support Department, European Space Agency, ESTEC, Postbus 299, NL-2200AG, Noordwijk, The Netherlands (4) Mission Analysis Office, European Space Agency, ESOC, Darmstadt, Germany ABSTRACT The Solar Orbiter mission is presently in assessment phase by the Science Payload and Advanced Concepts Office of the European Space Agency. The mission is confirmed in the Cosmic Vision programme, with the objective of a launch in October 2013 and no later than May 2015. The Solar Orbiter mission incorporates both a near-Sun (~0.22 AU) and a high-latitude (~ 35 deg) phase, posing new challenges in terms of protection from the intense solar radiation and related spacecraft thermal control, to remain compatible with the programmatic constraints of a medium class mission. This paper provides an overview of the assessment study activities, with specific emphasis on the definition of the model payload and its accommodation in the spacecraft. The main results of the industrial activities conducted with Alcatel Space and EADS-Astrium are summarized. Keywords: Solar physics, space weather, instrumentation, mission assessment, Solar Orbiter 1. INTRODUCTION The Solar Orbiter mission was first discussed at the Tenerife “Crossroads” workshop in 1998, in the framework of the ESA Solar Physics Planning Group. The mission was submitted to ESA in 2000 and then selected by ESA’s Science Programme Committee in October 2000 to be implemented as a flexi-mission, with a launch envisaged in the 2008- 2013 timeframe (after the BepiColombo mission to Mercury) [1]. -

ESA & ESOC Overview

NASA PM Challenge 2010 Developing the International Program/Project Management Community 9/10 February 2010 Dr. Bettina Böhm Program & Project Manager Career at ESA | Bettina Böhm | ESA/HQ | 23/11/09 | Page 1 Used with Permission PURPOSE OF ESA / ACTIVITIES “To provide for and promote, for exclusively Space science peaceful purposes, cooperation among Human spaceflight European states in space research and Exploration technology and their space applications.” Earth observation Launchers [Article 2 of ESA Convention] Navigation ESA is one of the few space agencies Telecommunications in the world to combine responsibility Technology in all areas of space activity. Operations Program & Project Manager Career at ESA | Bettina Böhm | ESA/HQ | 23/11/09 | Page 2 ESA FACTS AND FIGURES Over 30 years of experience 18 Member States 2080 staff, thereof 880 in Program Directorates, 790 in Operations and Technical Support and 410 in other Support Directorates 3 500 million Euros budget Over 60 satellites designed and tested Over 60 satellites operated in-flight and 8 missions rescued 16 scientific satellites in operation Five types of launcher developed More than 180 launches made Program & Project Manager Career at ESA | Bettina Böhm | ESA/HQ | 23/11/09 | Page 3 ESA Locations EAC (Cologne) Salmijaervi ESTEC Astronaut training (Noordwijk) Satellite technology development and testing Harwell ESOC ESA HQ (Darmstadt) (Paris) Brussels Satellite operations and ground system technology development ESAC (Villanueva de la Cañada Oberpfaffenhofen -

(IES) Measurement of the Development of Pickup Ions from Comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko

PUBLICATIONS Geophysical Research Letters RESEARCH LETTER The Rosetta Ion and Electron Sensor (IES) measurement 10.1002/2015GL063939 of the development of pickup ions from comet Key Point: 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko • IES observed low-energy ions in August 2014, at an 80 km distance R. Goldstein1, J. L. Burch1, P. Mokashi1, T. Broiles1, K. Mandt1, J. Hanley1, T. Cravens2, A. Rahmati2, from the comet M. Samara3, G. Clark3, M. Hässig1,4, and J. M. Webster1 1Southwest Research Institute, San Antonio, Texas, USA, 2Physics and Astronomy, University of Kansas, Lawrence, Kansas, USA, 3 4 Correspondence to: NASA Goddard Space Flight Center, Greenbelt, Maryland, USA, Physikalisches Institut, University of Bern, Bern, Switzerland R. Goldstein, [email protected] Abstract The Rosetta Ion and Electron Sensor (IES) has been measuring solar wind ions intermittently since exiting from hibernation in May 2014. On 19 August, when Rosetta was ~80 km from the comet Citation: Goldstein, R., et al. (2015), The Rosetta Ion 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko, which was ~3.5 AU from the Sun, IES began to see ions at its lowest energy and Electron Sensor (IES) measurement range, ~4–10 eV. We identify these as ions created from neutral species emitted by the comet nucleus, of the development of pickup ions from photoionized by solar UV radiation in the neighborhood of the Rosetta spacecraft (S/C), and attracted by the comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko, Geophys. Res. Lett., 42,3093–3099, small negative potential of the S/C resulting from the population of thermal electrons. Later, IES began to doi:10.1002/2015GL063939. see higher-energy ions that we identify as having been picked up and accelerated by the solar wind. -

Exploring the Solar Poles and the Heliosphere from High Helio-Latitude

A white paper submitted to ESA for the Voyage 2050 long- term plan ? A journey to the polar regions of a star: Exploring the solar poles and the heliosphere from high helio-latitude Louise Harra ([email protected]) and the solar polar team PMOC/WRC, Dorfstrasse 33, CH-7260 Davos Dorf & ETH-Zürich, Switzerland [Image: Polar regions of major Solar System bodies. Top left, clockwise - Near-surface zonal flows around the solar north pole Bogart et al. (2015); Earth’s changing magnetic field from ESA’s Swarm constellation; Southern polar cap of Mars from ESA’s ExoMars; Jupiter’s poles from the NASA Juno mission; Saturn’s poles from the NASA Cassini mission.] Overview We aim to embark on one of humankind’s great journeys – to travel over the poles of our star, with a spacecraft unprecedented in its technology and instrumentation – to explore the polar regions of the Sun and their effect on the inner heliosphere in which we live. The polar vantage point provides a unique opportunity for major scientific advances in the field of heliophysics, and thus also provides the scientific underpinning for space weather applications. It has long been a scientific goal to study the poles of the Sun, illustrated by the NASA/ESA International Solar Polar Mission that was proposed over four decades ago, which led to the flight of ESA’s Ulysses spacecraft (1990 to 2009). Indeed, with regard to the Earth, we took the first tentative steps to explore the Earth’s polar regions only in the 1800s. Today, with the aid of space missions, key measurements relating to the nature and evolution of Earth’s polar regions are being made, providing vital input to climate-change models. -

Alejandro Cardesín Moinelo ESA Science Operations Center Mars Express & Exomars 2016 (Slides Courtesy of Christian Erd & Peter Falkner, ESA-ESTEC)

Alejandro Cardesín Moinelo ESA Science Operations Center Mars Express & ExoMars 2016 (slides courtesy of Christian Erd & Peter Falkner, ESA-ESTEC) ESAC, 7th February 2017 Mission Flow Diagram Slide 2 Space Mission Timeline: Phases Slide 3 Science Mission Design Process Slide 4 Science Objectives – Requirements - Solutions Science Objective is the high level motivation • Which scientific question/application purpose shall the WHY? project address and what answer is sought Requirement is the translation of this objective into verifiable statements of what is needed to achieve the objective With detailed quantities (unambiguous) • WHAT? • Several levels of detail • Traceable, all the way back to the top level • Careful with conflicting requirements Solution is the response to the all requirements • There can be several solutions meeting requirements HOW? • Non-compliance needs to be negotiated Slide 5 Conflicting Requirements Farm “Optimal” Animal : Eierlegende Wollmilchsau (famous Austrian animal) Slide 6 Trade-off Trade-off allows exploring alternative solutions to a baseline Most common criteria: mass, cost budget; several System Performance system properties can be translated into them Power consumption generation of more power solar array size mass Higher telemetry volume larger HGA, more power for TM&C mass High performance complex solutions Cost more effort for verification Mass longer integration time cost Slide 7 Mission Segments, Systems & Subsystems Slide 8 Mission Analysis Launch Transfer trajectory Insertion into -

Galaxies and Stars Form and Evolve

BR-262 European Space Agency • 8-10 rue Mario-Nikis 75738 Paris Cedex 15 Tel. (33) 1.53.69.71.55 Fax (33) 1.53.69.76.90 There are also Public Relations offices at the following ESA establishments: • ESTEC Noordwijk The Netherlands Tel. (31) 71.565.3006 Fax (31) 71.565.6040 • ESOC Darmstadt Germany Tel. (49) 6151.90.2696 Exploring the Fax (49) 6151.90.2961 • EAC Cologne Germany formation of Tel. (49) 2203.60.010 Fax (49) 2203.60.0166 • ESRIN Frascati Galaxies and Italy Tel. (39) 6.94.18.02.60 Fax (39) 6.94.18.02.57 Stars ESA Science Programme Communication Service Tel: +31 71 565 3223 Fax: +31 71 565 4101 http://sci.esa.int HERSCHEL HERSCHEL a Contact: ESA Communications c/o ESTEC, PO Box 299, 2200 AG Noordwijk, The Netherlands Tel. (31) 71 565 3400 - Fax (31) 71 565 5433 a COVER_HERSCHEL.indd 1 22/8/07 13:06:16 About ESA The European Space Agency (ESA) was formed on 31 May 1975. It has 17 Member States: Austria, Belgium, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Ireland, Italy, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, Norway, Portugal, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland and the United Kingdom. The ESA Science Programme has launched a series of innovative and successful missions. Highlights of the programme include: Cassini-Huygens is one of the ISO, which studied cool gas clouds and most ambitious planetary exploration efforts planetary atmospheres. Everywhere it looked, ever attempted. After a seven-year journey, the it found water in surprising abundance. Cassini orbiter began studying the Saturnian system in great detail, and the Huygens probe descended onto Saturn’s giant moon Titan, , the first space observatory ever unveiling an amazing cold but Earth-like world. -

Ulyssesulysses

UlyssesUlysses Achievements: first in situ investigation of the inner heliosphere from the solar equator to the poles; first exploration of the dusk sector of Jupiter’s magnetosphere; fastest spacecraft at launch (15.4 km/s) Launch date: 6 October 1990 Mission end: planned September 2004 Launch vehicle/site: NASA Space Shuttle Discovery from Kennedy Space Center, USA Launch mass: 370 kg (including 55 kg scientific payload) Orbit: heliocentric, 1.34x5.4 AU, inclined 79.1° to ecliptic, 6.2 year period Principal contractors: Dornier (prime), British Aerospace (AOCS, HGA), Fokker (thermal, nutation damper), FIAR (power), Officine Galileo (Sun sensors), Laben (data handling), Thomson-CSF (telecommand), MBB (thrusters)] Ulysses is making the first-ever of the heliosphere, and slow wind study of the particles and fields in confined to the equatorial regions), the inner heliosphere at all solar the discovery that high- and low- latitudes, including the polar latitude regions of the heliosphere regions. A Jupiter flyby in February are connected in a much more 1992 deflected Ulysses out of the systematic way than previously ecliptic plane into a high-inclination thought, the first-ever direct solar orbit, bringing it over the Sun’s measurement of interstellar gas south pole for the first time in (both in neutral and ionised state) September 1994 and its north pole and dust particles, and the precise 10.5 months later. Ulysses spent a measurement of cosmic-ray isotopes. total of 234 days at latitudes >70°, These, together with numerous other reaching a maximum 80.2° in both important findings, have resulted in hemispheres. The mission was more than 700 publications to date originally to end in September 1995, in the scientific literature. -

The Exploration of the Heliosphere in Three Dimensions with Ulysses – a Case Study in International Cooperation

Fisk 16-12-2005 11:00 Pagina 15 15 The Exploration of the Heliosphere in Three Dimensions with Ulysses – A Case Study in International Cooperation L.A. Fisk Department of Atmospheric, Oceanic and Space Sciences, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, USA On 6 October 1990, the Ulysses spacecraft was launched to begin the explo- ration of the heliosphere in three dimensions, that vast region of space carved out by the influence of the Sun. A European Space Agency (ESA) spacecraft, launched and tracked by NASA, with instruments provided by both Europe and the United States, Ulysses is a classic example of international cooperation. Like all classic examples, however, Ulysses provides lessons on what to do and what not to do. (The Ulysses mission has had many names, from the Out-of-the- Ecliptic Mission to the International Solar Polar Mission to its current name, Ulysses, which was given to it in 1984. The mission has been the same, but the name has changed, and so for simplicity in this article, we will use the name Ulysses throughout.) Figure 1. Ulysses, also known as the Out-of-the-Ecliptic or International Solar Polar Mission The Solar System and Beyond: Ten Years of ISSI Fisk 16-12-2005 11:00 Pagina 16 16 L.A. Fisk Ulysses has been a long saga, dating from the early 1970s and continuing even today. It had its initial trials and, like all good stories, it ends in triumph. I will relate that story here, for the lessons it provides. The Ulysses story is also inter- twined with the ISSI story.