Title <Chapter 1> Democracy and Vigilantism: the Spread of Gau

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Contest of Indian Secularism

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Helsingin yliopiston digitaalinen arkisto THE CONTEST OF INDIAN SECULARISM Erja Marjut Hänninen University of Helsinki Faculty of Social Sciences Political History Master’s thesis December 2002 Map of India I INTRODUCTION...........................................................................................................1 PRESENTATION OF THE TOPIC ....................................................................................................................3 AIMS ......................................................................................................................................................... 5 SOURCES AND LITERATURE ......................................................................................................................7 CONCEPTS ............................................................................................................................................... 12 SECULARISM..............................................................................................................14 MODERNITY ............................................................................................................................................ 14 SECULARISM ........................................................................................................................................... 16 INDIAN SECULARISM .............................................................................................................................. -

Narendra Modi Tops, Yogi Adityanath Enters List

Vol: 23 | No. 4 | April 2017 | R20 www.opinionexpress.in A MONTHLY NEWS MAGAZINE Hindu-Americans divided on Trump’s immigration policy COVER STORY SOARING HIGH The ties between India and Israel were never better The Pioneer Most Powerful Indians in 2017: Narendra Modi tops,OPINI YogiON EXPR AdityanathESS enters list 1 2 OPINION EXPRESS editorial Modi, Yogi & beyond RNI UP–ENG 70032/92, Volume 23, No 4 EDITOR Prashant Tewari – BJP is all set for the ASSOCiate EDITOR Dr Rahul Misra POLITICAL EDITOR second term in 2019 Prakhar Misra he surprise appointment of Yogi Adityanath as Uttar Pradesh Chief Minister post BUREAU CHIEF party’s massive victory in the recently concluded assembly elections indicates that Gopal Chopra (DELHI), Diwakar Shetty BJP/RSS are in mission mode for General Election 2019. The new UP CM will (MUMBAI), Sidhartha Sharma (KOLKATA), T ensure strict saffron legislation, compliance and governance to Lakshmi Devi (BANGALORE ) DIvyash Bajpai (USA), KAPIL DUDAKIA (UNITED KINGDOM) consolidate Hindutva forces. The eighty seats are vital to BJP’s re- Rajiv Agnihotri (MAURITIUS), Romil Raj election in the next parliament. PM Narendra Modi is world class Bhagat (DUBAI), Herman Silochan (CANADA), leader and he is having no parallel leader to challenge his suprem- Dr Shiv Kumar (AUS/NZ) acy in the country. In UP, poor Akhilesh and Rahul were just swept CONTENT partner aside-not by polarization, not by Hindu consolidation but simply by The Pioneer Modi’s far higher voltage personality. Pratham Pravakta However the elections in five states have proved that BJP is not LegaL AdviSORS unbeatable. -

Annual-Activity-Report-2018.Pdf

Published in July 2018 by Dr. Syama Prasad Mookerjee Research Foundation 9, Ashok Road, New Delhi-110001 Tel: +91-(0)11-23005850 E-mail: [email protected] Web: www.spmrf.org Follow us : /spmrfoundation @spmrfoundation /spmrf Copyright © Dr. Syama Prasad Mookerjee Research Foundation Design : Ajit Kumar Singh 2 Annual Report 2018 Dr. Syama Prasad Mookerjee Research Foundation, New Delhi Annual Activity Report 2018 Annual Report 2018 3 Contents Director’s Desk 05 About SPMRF 07 Activities 08 SPMRF Round Table Week 29 International Events 36 Nationalistonline.com (Hindi/English) Web 37 Portal The Nationalist E-Journals 38 Publications 39 Syama Prasad Mookerjee Resource Center 40 Reports 41 Booklets 42 SPMRF – Trustees 43 SPMRF Advisory Council 44 SPMRF Team 46 4 Annual Report 2018 Director’s Desk t the end of our annual journey, I would like to broadly outline the vision of our institution, which is to create a framework Ato spur knowledge, ideas, creative thinking and integral humanism as an ideology with public policy to influence policy decisions for development of the nation. “Whatever work you undertake, do it seriously, thoroughly and well; never leave it half-done or undone, never feel yourself satisfied unless and until you have given it your very best. Cultivate the habits of discipline and toleration. Surrender not the convictions you hold dear but learn to appreciate the points of view of your opponents.” Quote from a speech delivered by Dr. Syama Prasad Mookerjee at Scottish Church College, Kolkata on 7th December 1935. Dr. Anirban Ganguly Dr. Syama Prasad Mookerjee’s words mentioned above echo in our institution, for attaining afocus at recycling research that aims to solve policy problems the objective of educating a wider public opinion. -

The State, Democracy and Social Movements

The Dynamics of Conflict and Peace in Contemporary South Asia This book engages with the concept, true value, and function of democracy in South Asia against the background of real social conditions for the promotion of peaceful development in the region. In the book, the issue of peaceful social development is defined as the con- ditions under which the maintenance of social order and social development is achieved – not by violent compulsion but through the negotiation of intentions or interests among members of society. The book assesses the issue of peaceful social development and demonstrates that the maintenance of such conditions for long periods is a necessary requirement for the political, economic, and cultural development of a society and state. Chapters argue that, through the post-colo- nial historical trajectory of South Asia, it has become commonly understood that democracy is the better, if not the best, political system and value for that purpose. Additionally, the book claims that, while democratization and the deepening of democracy have been broadly discussed in the region, the peace that democracy is supposed to promote has been in serious danger, especially in the 21st century. A timely survey and re-evaluation of democracy and peaceful development in South Asia, this book will be of interest to academics in the field of South Asian Studies, Peace and Conflict Studies and Asian Politics and Security. Minoru Mio is a professor and the director of the Department of Globalization and Humanities at the National Museum of Ethnology, Japan. He is one of the series editors of the Routledge New Horizons in South Asian Studies and has co-edited Cities in South Asia (with Crispin Bates, 2015), Human and International Security in India (with Crispin Bates and Akio Tanabe, 2015) and Rethinking Social Exclusion in India (with Abhijit Dasgupta, 2017), also pub- lished by Routledge. -

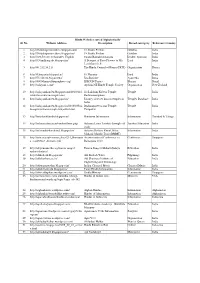

1.Hindu Websites Sorted Alphabetically

Hindu Websites sorted Alphabetically Sl. No. Website Address Description Broad catergory Reference Country 1 http://18shaktipeetasofdevi.blogspot.com/ 18 Shakti Peethas Goddess India 2 http://18shaktipeetasofdevi.blogspot.in/ 18 Shakti Peethas Goddess India 3 http://199.59.148.11/Gurudev_English Swami Ramakrishnanada Leader- Spiritual India 4 http://330milliongods.blogspot.in/ A Bouquet of Rose Flowers to My Lord India Lord Ganesh Ji 5 http://41.212.34.21/ The Hindu Council of Kenya (HCK) Organisation Kenya 6 http://63nayanar.blogspot.in/ 63 Nayanar Lord India 7 http://75.126.84.8/ayurveda/ Jiva Institute Ayurveda India 8 http://8000drumsoftheprophecy.org/ ISKCON Payers Bhajan Brazil 9 http://aalayam.co.nz/ Ayalam NZ Hindu Temple Society Organisation New Zealand 10 http://aalayamkanden.blogspot.com/2010/11/s Sri Lakshmi Kubera Temple, Temple India ri-lakshmi-kubera-temple.html Rathinamangalam 11 http://aalayamkanden.blogspot.in/ Journey of lesser known temples in Temples Database India India 12 http://aalayamkanden.blogspot.in/2010/10/bra Brahmapureeswarar Temple, Temple India hmapureeswarar-temple-tirupattur.html Tirupattur 13 http://accidentalhindu.blogspot.in/ Hinduism Information Information Trinidad & Tobago 14 http://acharya.iitm.ac.in/sanskrit/tutor.php Acharya Learn Sanskrit through self Sanskrit Education India study 15 http://acharyakishorekunal.blogspot.in/ Acharya Kishore Kunal, Bihar Information India Mahavir Mandir Trust (BMMT) 16 http://acm.org.sg/resource_docs/214_Ramayan An international Conference on Conference Singapore -

The 40Th Annual Conference on South Asia (2011)

2011 40th Annual Conference on South Asia Paper Abstracts Center for South Asia University of Wisconsin - Madison Aaftaab, Naheed Claiming Middle Class: Globalization, IT, and exclusionary practices in Hyderabad In this paper, I propose that middle class identity in the IT sector can be read as part of an “identity politics” that claim certain rights and benefits from governmental bodies both at the national and international levels. India’s economic growth since the 1991 liberalization has been attended by the growth of the middle classes through an increase in employment opportunities, such as those in the IT sector. The claims to middle class status are couched in narratives of professional affiliations that shape culturally significant components of middle class identities. The narratives rely on the ability of IT professionals to reconcile the political identities of nationalism while simultaneously belonging to a global work force. IT workers and the industry at large are symbols of India’s entry into the global scene, which, in turn, further reinforces the patriotic and nationalist rhetoric of “Indianness.” This global/national identity, however, exists through exclusionary practices that are evident in the IT sector despite the management’s assertions that the industry’s success is dependent on “merit based” employment practices. Using ethnographic data, I will examine middle class cultural and political claims as well as exclusionary practices in professional settings of the IT industry in order to explore the construction of new forms of identity politics in India. 40th Annual Conference on South Asia, 2011 1 Acharya, Anirban Right To (Sell In) The City: Neoliberalism and the Hawkers of Calcutta This paper explores the struggles of urban street vendors in India especially during the post liberalization era. -

Hindu Websites Sorted Alphabetically Sl

Hindu Websites sorted Alphabetically Sl. No. Website Address Description Broad catergory Reference Country 1 http://18shaktipeetasofdevi.blogspot.com/ 18 Shakti Peethas Goddess India 2 http://18shaktipeetasofdevi.blogspot.in/ 18 Shakti Peethas Goddess India 3 http://199.59.148.11/Gurudev_English Swami Ramakrishnanada Leader- Spiritual India 4 http://330milliongods.blogspot.in/ A Bouquet of Rose Flowers to My Lord India Lord Ganesh Ji 5 http://41.212.34.21/ The Hindu Council of Kenya (HCK) Organisation Kenya 6 http://63nayanar.blogspot.in/ 63 Nayanar Lord India 7 http://75.126.84.8/ayurveda/ Jiva Institute Ayurveda India 8 http://8000drumsoftheprophecy.org/ ISKCON Payers Bhajan Brazil 9 http://aalayam.co.nz/ Ayalam NZ Hindu Temple Society Organisation New Zealand 10 http://aalayamkanden.blogspot.com/2010/11/s Sri Lakshmi Kubera Temple, Temple India ri-lakshmi-kubera-temple.html Rathinamangalam 11 http://aalayamkanden.blogspot.in/ Journey of lesser known temples in Temples Database India India 12 http://aalayamkanden.blogspot.in/2010/10/bra Brahmapureeswarar Temple, Temple India hmapureeswarar-temple-tirupattur.html Tirupattur 13 http://accidentalhindu.blogspot.in/ Hinduism Information Information Trinidad & Tobago 14 http://acharya.iitm.ac.in/sanskrit/tutor.php Acharya Learn Sanskrit through self Sanskrit Education India study 15 http://acharyakishorekunal.blogspot.in/ Acharya Kishore Kunal, Bihar Information India Mahavir Mandir Trust (BMMT) 16 http://acm.org.sg/resource_docs/214_Ramayan An international Conference on Conference Singapore -

Article Does Surveillance Intersect with Religious

Does Surveillance Intersect with Religious Article Freedom? The Dialectics of Religious Tolerance and (Re)Proselytism in India Today Jijo James Indiparambil Katholieke Universiteit Leuven, Belgium [email protected] Abstract An individual is enveloped today by a vast network of automated, integrated, globalised, and ubiquitous surveillance that sweeps into all spheres of one’s life. One’s religious adherences and practices are no exception to this. The surveillance of religion, seen globally today, is yet another intrusion into the lives of people in India. Recently, it has taken on another dimension as issues of proselytism (conversion) and the movement of “Ghar Wapsi” or homecoming (reconversion) increasingly endanger the peaceful coexistence of India’s population. Growing religious intolerance to religious minorities under the influence of Hindutva—an ideological persuasion to establish the hegemony of Hindu beliefs and way of life—increases this distorted behaviour and encourages Hindu fundamentalism. This paper investigates this issue of state surveillance of religious minorities, focusing on certain political conspiracies and the perverted behaviour of some religious fundamentalist groups operating behind the veneer of constitutional secularism and state-determined coercive power control. With an analytical and critical discourse methodology, this paper argues that minority religious communities in India are key targets of surveillance and subject to manipulative (political and religious) interests that go against Indian liberalism. Thus, we find in the Indian case a categorical dissimilarity with the West regarding the focus of religious surveillance. Introduction The surveillance of religion, now witnessed around the globe, is an emerging issue of controversy in India. To many, it seems yet another intrusion into individual lives. -

E Sangh Parivar

Shadow Armies Fringe Organizations and Foot Soldiers of Hindutva Dhirendra K. Jha JUGGERNAUT BOOKS KS House, 118 Shahpur Jat, New Delhi 110049, India First published in hardback by Juggernaut Books 2017 Published in paperback 2019 Copyright © Dhirendra K. Jha 2017 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, transmitted, or stored in a retrieval system in any form or by any means without the written permission of the publisher. e views and opinions expressed in this book are the author’s own. e facts contained herein were reported to be true as on the date of publication by the author to the publishers of the book, and the publishers are not in any way liable for their accuracy or veracity. ISBN 9789353450199 Typeset in Adobe Caslon Pro by R. Ajith Kumar, New Delhi Printed at Manipal Technologies Ltd, India Contents Introduction 1. Sanatan Sanstha 2. Hindu Yuva Vahini 3. Bajrang Dal 4. Sri Ram Sene 5. Hindu Aikya Vedi 6. Abhinav Bharat 7. Bhonsala Military School 8. Rashtriya Sikh Sangat Notes Acknowledgements A Note on the Author Introduction India has seen astonishing growth in the politics of Hindutva over the last three decades. Several strands of this brand of politics – not just the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) but also those working for it in the shadows – have shot into prominence. ey are all fuelled by a single motive: to ensure that one particular community, the Hindus, has the exclusive right to define our national identity. e Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS), a pan-Indian organization comprising chauvinistic Hindu men, is the vanguard of this politics. -

When Cop Joined Kar Sevaks to Shout Jai Shri Ram OFFERS FADNAVIS SANJAY KAW Name of Sanjay Kaul

c m y k c m y k HE SIAN GE T NEWA DELHI SUNDAY 10 NOVEMBER 2019 A www.asianage.com RNI No. 57290/94, Regd No: DL-SW-05/4189/15-17 Vol. 26 No. 264 | 48 PAGES | `5.00 RAM LALLA COMES HOME, A NEW MASJID TO RISE SC calls Babri’s demolition a crime, but says Hindus’ claim on land is stronger 5 judges pronounce TODAY IS the day to unanimous verdict forget any bitterness one may have; there PRAMOD KUMAR is no place for fear, NEW DELHI, NOV. 9 INSiDE bitterness and In an unprecedented case negativity in new based on faith and belief, RAM TEMPLE India the Supreme Court on Saturday “unanimously” NARENDRA MODI, paved the way for the con- WORK TO Prime Minister struction of Lord Ram’s temple at Ayodhya as it BEGIN IN APRIL IT IS A moment of rejected the Muslim claim over the disputed site and ● The RSS is now hop- fulfilment for me handed over the entire ing to lay the temple’s because God 1,500 square yard of the foundation stone on the Almighty had given “composite” disputed area ‘Ram Navmi’ next April. me an opportunity to comprising the inner and make my own humble the outer court yard of the ■ REPORT ON PAGE 4 now demolished Babri contribution to the Masjid to a trust that mass movement would construct the tem- ple and would be set up by RAJIV GANDHI’S L.K. ADVANI, the Central government in Veteran BJP leader next three months. BLUNDERS The disputed land would THE SUPREME remain in the custody of HELPED BJP RISE Court’s the statutory receiver till verdict has come. -

Case Comment on S.P. Mittal V. Union of India

An Open Access Journal from The Law Brigade (Publishing) Group 142 ELECTORAL POLITICS AND SECULARISM: LEGAL FACET Written by Debasmita Bhattacharjee* & Carol Elsa Zachariah** * 3rd Year BA LLB Student, School of Law, Christ University ** 3rd Year BA LLB Student, School of Law, Christ University INTRODUCTION A layman perception of secularism will encompass a view of religious coexistence. However, such a narrow thought doesn't suffice the true spirit of the same. As quoted by Shashi Tharoor, the Member of Parliament, Lok Sabha from Thiruvananthapuram, Kerala, “Western dictionaries define secularism as absence of religion but Indian secularism does not mean that irreligiousness. It means profusion of religions." Mere coexistence is insufficient to indicate if equality persists between the existing religions.1 Thus, secularism might fail to serve the very purpose for which it was introduced into the Indian society: equal protection to all religions. India might have officially declared itself a secular country in the year 1976 when the words secular and socialist were added to the Preamble through the 42nd amendment, but a very careful analysis of the Constitution of India will very well indicate that secularism had always been an innate part of the political ambition of the Drafting Committee. Article 15 under Chapter III of the Constitution of India dictates that no individual will be discriminated by the state on the ground of religions. Other fundamental rights which supplement the efforts in preserving the status of a secular state include articles 16, 17, 25, 26, 27 and 28. In Chapter IV, articles 44 and 46 highlight the state's endeavour to further ensure equality among religions through a mechanism of Uniform Civil Code and through promotion of the economic and 1 Historian Romila Thapar Breaks Down What Secularism Is And Is Not In The Indian Context, YOUTH KI AWAAZ (2018), https://www.youthkiawaaz.com/2015/10/secularism-in-india-romila-thapar/ (last visited May 31, 2018). -

Constructing Nation and History

Constructing Nation and History Hindu Mahasabha in Colonial North India 1915-1930 Prabhu Narain Bapu Thesis submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of Oriental and African Studies University of London November 2009 ProQuest Number: 11010467 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 11010467 Published by ProQuest LLC(2018). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 Dedicated to ... Gurdwara Sri Guru Singh Sabha, Southall, London Gurdwara Guru Nanak Nishkam Sewak Jatha [UK], Hounslow, London Gurdwara Sri Guru Singh Sabha, Hounslow, London Declaration for PhD thesis I have read and understood regulation 17.9 of the Regulations for students of the School of Oriental and African Studies concerning plagiarism.I undertake that all the material presented for examination is my own work and has not been written for me, in whole or in part by any other person.I also undertake that any quotation or paraphrase from the published or unpublished work of another person has been duly acknowledged Iin present the