ERICAN LOCAL COLOR in the BRITISH ISLES Lawson, Jr

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ina Coolbrith of California's "Overland Trinity95 by BENJAMIN DE CASSERES

Boolcs and the Book World of The Sun, December 7, 1919. 15 Ina Coolbrith of California's "Overland Trinity95 By BENJAMIN DE CASSERES. written, you know. I have just sent down ASTWARD the star of literary cm-- town for one of my books, want 'A J and I pire takes its way. After twenty-liv-e to paste a photograph as well as auto- years Ina Donna Coolbrith, crowned graph in it to mail to you. poet laureate of California by the Panama-P- "The old Oakland literary days! Do acific Exposition, has returned to yon know you were the first. one who ever New York. Her house on Russian Hill, complimented me on my choice of reading San Francisco, the aristocratic Olympus matter? Nobody at home bothered then-hea- of the Musaj of the Pacific slope, stands over what I read. I was an eager, empty. thirsty, hungry little kid and one day It is as though California had closed a k'Prsmmm mm m:mmm at the library I drew out a volume on golden page of literary and artistic mem- Pizzaro in Pern (I was ten years old). ories in her great epic for the life of You got the book and stamped it for me; Miss Coolbrith 'almost spans the life of and as you handed it to me you praised California itself. Her active and acuto me for reading books of that nature. , brain is a storehouse of memories and "Proud ! If you only knew how proud ' anecdote of those who have immortalized your words made me! For I thought a her State in literature Bret Harte, Joa- great deal of you. -

Hclassification

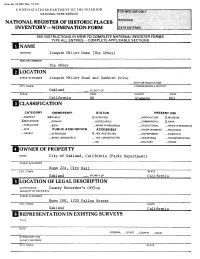

Form No. 10-300 (Rev. 10-74) UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OE THE INTERIOR NATIONAL PARK SERVICE NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES INVENTORY -- NOMINATION FORM SEE INSTRUCTIONS IN HOW TO COMPLETE NATIONAL REGISTER FORMS TYPE ALL ENTRIES -- COMPLETE APPLICABLE SECTIONS [NAME HISTORIC Joaquin Miller Home (The Abbey) AND/OR COMMON The Abbey LOCATION STREETS.NUMBER Joaquin Miller Road and Sanborn Drive _NOT FOR PUBLICATION CITY, TOWN CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT Oakland _.. VICINITY OF STATE CODE COUNTY CODE California 06 AT ameda 001 HCLASSIFICATION CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS PRESENT USE —DISTRICT XXPUBLIC X-OCCUPIED _ AGRICULTURE X_MUSEUM J^BUILDINGIS) —PRIVATE —UNOCCUPIED —COMMERCIAL X_PARK —STRUCTURE —BOTH —WORK IN PROGRESS —EDUCATIONAL —PRIVATE RESIDENCE —SITE PUBLIC ACQUISITION ACCESSIBLE —ENTERTAINMENT —RELIGIOUS —OBJECT _IN PROCESS X-YES: RESTRICTED —GOVERNMENT —SCIENTIFIC —BEING CONSIDERED — YES: UNRESTRICTED —INDUSTRIAL —TRANSPORTATION _NO —MILITARY —OTHER: OWNER OF PROPERTY NAME City of Oakland, California (Parks Department) STREET & NUMBER Room 224, City Hall CITY, TOWN STATE Oakland VICINITY OF California COURTHOUSE, County Recorder ! s Office REGISTRY OF DEEDS,ETC. STREET & NUMBER Room 100^ 1225 Fallen Street CITY. TOWN STATE Oakland California REPRESENTATION IN EXISTING SURVEYS TITLE DATE .FEDERAL _STATE __COUNTY _LOCAL DEPOSITORY FOR SURVEY RECORDS CITY, TOWN DESCRIPTION CONDITION CHECK ONE CHECK ONE —EXCELLENT -DETERIORATED —UNALTERED XXORIGINALSITE _MOVED DATE. X-GOOD _RUINS X_ALTERED _FAIR _UNEXPOSED DESCRIBETHE PRESENT AND ORIGINAL (IF KNOWN) PHYSICAL APPEARANCE The Joaquin Miller House is a small three-part frame building at the foot of the steep hills East of Oakland California. Composed of three single rooms joined together, the so-called "Abbey" must be seen as the most provincial of efforts to impose gothic-revival detail upon the three rooms. -

The American Side of the Line: Eagle City's Origins As an Alaska Gold Rush Town As

THE AMERICAN SIDE OF THE LINE Eagle City’s Origins as an Alaskan Gold Rush Town As Seen in Newspapers and Letters, 1897-1899 National Park Service Edited and Notes by Chris Allan THE AMERICAN SIDE OF THE LINE Eagle City’s Origins as an Alaskan Gold Rush Town National Park Service Yukon-Charley Rivers National Preserve 2019 Acknowledgments I want to thank the staff of the Alaska State Library’s Historical Collections, the University of Alaska Fairbanks’s Alaska and Polar Regions Collections & Archives, the University of Washington’s Special Collections, and the Eagle Historical Society for caring for and making available the photographs in this volume. For additional copies contact: Chris Allan National Park Service 4175 Geist Road Fairbanks, Alaska 99709 Printed in Fairbanks, Alaska February 2019 Front Cover: Buildings in Eagle’s historic district, 2007. The cabin (left) dates from the late 1890s and features squared-off logs and a corrugated metal roof. The red building with clapboard siding was originally part of Ft. Egbert and was moved to its present location after the fort was decommissioned in 1911. Both buildings are owned by Dr. Arthur S. Hansen of Fairbanks. Photograph by Chris Allan, used with permission. Title Page Inset: Map of Alaska and Canada from 1897 with annotations in red from 1898 showing gold-rich areas. Note that Dawson City is shown on the wrong side of the international boundary and Eagle City does not appear because it does not yet exist. Courtesy of Library of Congress (G4371.H2 1897). Back Cover: Miners at Eagle City gather to watch a steamboat being unloaded, 1899. -

Public Opinion and News Reporting: Different Viewpoints, Changing Perspectives

Public Opinion and News Reporting: Different Viewpoints, Changing Perspectives Grades: 7-HS Subjects: History, Oregon History, Civics, Social Studies Suggested Time Allotment: 1-2 class periods Lesson Background: Our impressions of events can often be influenced by the manner in which they are reported to us in the media. Begin by staging a class discussion of some recent news event(s) that have caused controversy. Can the students think of any news stories that strongly divide public opinions? Any that have been reported in a variety of different ways, depending on which television channels you watch or magazines you read? Can they think of examples where they thought one way or formed a certain opinion about a certain news event, only to have their minds change and opinion shift later, when more information came to light in the media? Moving on from this discussion, the lesson can demonstrate these issues of perspective. Lesson #1: Joaquin Miller—Genius or Cad? Joaquin Miller was the pen name of Cincinnatus Heine Miller, a colorful and controversial poet of the nineteenth century. (Read a detailed biography of Joaquin Miller on Wikipedia, here.) Known in his day as the ‘Poet of the Sierras,’ the ‘Byron of the Rockies,’ and the ‘Bard of Oregon,’ Miller became a celebrity throughout the United States, and especially in England. He was an associate of such enduring literary figures as Ambrose Bierce and Brett Hart. However, it could be argued that Miller’s fame came more from the popular image he created for himself—frontiersman, outdoorsman—than from the actual quality of his literary work. -

Americana Bibliographies Books in All Fields

Sale 490 Thursday, October 11, 2012 11:00 AM Fine Literature - Americana Bibliographies Books in All Fields Auction Preview Tuesday, October 9, 9:00 am to 5:00 pm Wednesday, October 10, 9:00 am to 5:00 pm Thursday, October 11, 9:00 am to 11:00 am Other showings by appointment 133 Kearny Street 4th Floor:San Francisco, CA 94108 phone: 415.989.2665 toll free: 1.866.999.7224 fax: 415.989.1664 [email protected]:www.pbagalleries.com REAL-TIME BIDDING AVAILABLE PBA Galleries features Real-Time Bidding for its live auctions. This feature allows Internet Users to bid on items instantaneously, as though they were in the room with the auctioneer. If it is an auction day, you may view the Real-Time Bidder at http://www.pbagalleries.com/realtimebidder/ . Instructions for its use can be found by following the link at the top of the Real-Time Bidder page. Please note: you will need to be logged in and have a credit card registered with PBA Galleries to access the Real-Time Bidder area. In addition, we continue to provide provisions for Absentee Bidding by email, fax, regular mail, and telephone prior to the auction, as well as live phone bidding during the auction. Please contact PBA Galleries for more information. IMAGES AT WWW.PBAGALLERIES.COM All the items in this catalogue are pictured in the online version of the catalogue at www.pbagalleries. com. Go to Live Auctions, click Browse Catalogues, then click on the link to the Sale. CONSIGN TO PBA GALLERIES PBA is always happy to discuss consignments of books, maps, photographs, graphics, autographs and related material. -

Literature in Rochester 1865 - 1905 by NATALIE F

Edited by DEXTER PERKINS, City HirtoGm and BLAKE MCKELVBY. Assistant City Hirtorian VOL. x JANUARY, 1948 No. 1 Literature in Rochester 1865 - 1905 By NATALIE F. HAWLEY At the end of the Civil War, Rochesterians-along with Americans elsewhere-became increasingly absorbed in the commercial and in- dustrial activities which were mushrooming all over the land. A city far different from the Yankee town of the fifties was developing along the Genesee. In the bustle of expansion, much of the old classical tradition was neglected and many conventional social patterns were outgrown. But in due course, increasing wealth, a new emphasis upon social events and social accomplishments, provided the occasion for an earnest, if somewhat indiscriminate search for culture. Social pretensions alone could not account for the revival of the literary arts however. The club movement, growing from a need to replace the inadequate social groups of earlier days, and accelerated by the increasing activity of women as society leaders, gave real nourishment to literary interests. It was in these social-literary clubs that the sober scholarship of local professors and theologians, at a discount for many years, worked best to provide a sound base for the creative and critical efforts of those newly awakened to the pleasures of literature. Out of an abundance of amorphous material, we have tried to choose those groups and individuals who most surely represent the significant trends and tastes of the period rather than to select our own favorites or to establish an arbitrary standard of the best which Roch- ester has contributed to prose and poetry. -

Joaquin and Juanita Miller Collection

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt9x0nd6bs No online items Guide to the Joaquin and Juanita Miller Collection Processed by Katie Hassan and Kelley Wolfe Bachli Special Collections, Honnold/Mudd Library Libraries of The Claremont Colleges 800 Dartmouth Avenue Claremont, CA 91711 Phone: (909) 607-3977 Fax: (909) 621-8681 Email: [email protected] URL: http://libraries.claremont.edu/sc/default.html © 2007 Claremont University Consortium. All rights reserved. Guide to the Joaquin and Juanita H2007.4 1 Miller Collection Guide to the Joaquin and Juanita Miller Collection Collection number: H2007.4 Special Collections, Honnold/Mudd Library Libraries of The Claremont Colleges Claremont, California Processed by: Processed by Katie Hassan and Kelley Wolfe Bachli Date Completed: 2007 September Encoded by: Kelley Wolfe Bachli © 2004 Claremont University Consortium. All rights reserved. Descriptive Summary Title: Joaquin and Juanita Miller collection Dates: 1878-1941 Collection number: H2007.4 Creator: Miller, Joaquin, 1837-1913 Creator: Miller, Juanita Joaquina, 1880-1970 Collection Size: 2 boxes Repository: Claremont Colleges. Library. Special Collections, Honnold/Mudd Library. Claremont, CA 91711 Abstract: The collection contains correspondence, photographs, printed materials, and manuscript materials from 1878-1941. Among the manuscript material is an unpublished manuscript titled �When I was Emperor.� All of the photographs are of Joaquin Miller, some accompanied by his daughter and Dr. Frederick Cook. Physical location: Please consult repository. Languages: Languages represented in the collection: English Access Collection open for research. Publication Rights All requests for permission to publish must be submitted in writing to Special Collections. Preferred Citation [Identification of item], Joaquin and Juanita Miller collection. -

Chapter 20: Literature: Joaquin Miller

Mount Shasta Annotated Bibliography Chapter 20 Literature: Joaquin Miller "There loomed Mount Shasta, with which my name, if remembered at all, will be remembered." So wrote Joaquin Miller in his 1873 classic Mt. Shasta novel, Life Amongst the Modocs: Unwritten History. Miller was a young gold miner in the Mt. Shasta region from 1854 until 1857. Remarkable among extant Miller materials is his 1850s diary which, among other things, records his living for an entire year in Squaw Valley on the southern flank of Mt. Shasta. It was a year in which he lived with an Indian woman among her tribe. His experience living among the Indians, mostly out of contact with white people, gave him an unprecedented sympathy for the Indian and for nature. In later life Miller wrote book after book and poem after poem utilizing the themes he had learned from experience during those early years. Several of Miller's books, including the 1873 Unwritten History..., the 1884 Memorie and Rime, and the 1900 True Bear Stories, contain considerable autobiographical material about his life at Mt. Shasta. Note that Miller was a man far ahead of his times, and critics up until the late 20th Century did not fully appreciate his unconventional philosophy. Miller created a retreat for the homeless, spearheaded the first California Arbor Day, personally planted thousands of trees over a period of decades, founded an artistic commune based on the teachings of silence and nature, and wanted it to be known that he worked with his hands. Miller's 1885 log cabin, which still stands in Rock Creek National Park in Washington, D. -

Joaquin Miller, Poet Laureate of Oregon

Joaquin Miller, Poet Laureate of Oregon By Thomas Leander Moorhouse Joaquin Miller was an Oregon writer and poet who first found fame in Britain by portraying himself as a flamboyant western frontiersman, telling colorfully exaggerated stories, wearing buckskin clothing and a Mexican sombrero, and, later in life, sporting a flowing white beard. Amateur Pendleton photographer Thomas Leander “Lee” Moorhouse took this photograph in about 1907, perhaps when Miller was visiting eastern Oregon. In 1852, Cincinnatus Hiner Miller (1837-1913) moved with his parents to the Willamette Valley. He lived in various parts of the state and at one time was the editor of the Eugene Democratic Register. Later on, he and his second wife, poet Minnie Myrtle, lived in a cabin in Canyon City, Grant County, which has since been preserved as a tourist attraction and museum. In 1870, Miller left his wife and Oregon, moving to San Francisco and then Great Britain in an effort to find fame as a poet and writer. He changed his name to Joaquin in honor of a legendary California outlaw, Joaquin Murieta, and found success with the 1871 publication of his book, Songs of the Sierras. In early 1880s, Miller returned to the United States and lived for a while in a cabin he built in Washington D.C. before moving to Oakland, California. A tireless self-promoter, Miller told stories about gold mining and Indian fighting that probably had little connection to his actual life history. Accused of being a liar, Miller reportedly responded “I am not a liar. I simply exaggerate the truth.” Some critics have asserted that Miller’s literary work was unoriginal and mediocre. -

Languages for America”: Dialects, Race, and National

UNIVERSITY OF OKLAHOMA GRADUATE COLLEGE “LANGUAGES FOR AMERICA”: DIALECTS, RACE, AND NATIONAL IDENTITY IN NINETEENTH-CENTURY AMERICAN LITERATURE A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE FACULTY in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY By THOMAS LEE WHITE, JR. Norman, Oklahoma 2011 “LANGUAGES FOR AMERICA”: DIALECTS, RACE, AND NATIONAL IDENTITY IN NINETEENTH-CENTURY AMERICAN LITERATURE A DISSERTATION APPROVED FOR THE DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH BY Dr. Daniel Cottom, Chair Dr. Francesca Sawaya Dr. Timothy Murphy Dr. Ronald Schliefer Dr. Benjamin Alpers © Copyright by THOMAS LEE WHITE, JR. 2011 All Rights Reserved. Acknowledgements To my God, thank you for your grace. To my beautiful wife, Tara, and family, thank you for your love. To the members of my committee, specifically Dr. Daniel Cottom, thank you for your patience. iv Table of Contents Introduction…………………………………………………………………………1 “By Shaint Patrick”: Irish American Dialect in H.H. Brackenridge’s Modern Chivalry ……………………………………………………...……………..26 “Ain’t Princerple Precious?”: Yankee Dialect in James Russell Lowell’ s The Biglow Papers …………………………………………………………74 Cooking the “Liddle Tedails”: German American Dialect in Charles Godfrey Leland’s Hans Breitmann Ballads ………………………………………122 The “Melican Man”: Asian American Dialect and Bret Harte’s Truthful James Poems…………………………………………………….……………….165 “Delinquents of Some Kind”: White and Black Dialect in Charles W. Chesnutt’s The Colonel’s Dream…….………………………………….. 191 v Abstract I argue the process of institutionalizing linguistic stereotypes began as authors during the nineteenth century pursued ways of characterizing the voices of literary figures using nontraditional languages. Literary dialects became a method for visualizing perceived racial differences among various minority groups and influenced the stereotypes associated with each discourse community. -

The Indiana Boyhood of the Poet of the Sierras by GLENE

The Indiana Boyhood of the Poet of the Sierras By GLENE. VEACH Joaquin Miller’s name has long been a distinguished name. If he had written nothing else, that grand poem “The Great Discoverer” would have assured his fame. Who is not familiar with the lilting cadence of this, his most poignant masterpiece? It is to be found in numerous an- thologies and was long a classic of the grade school readers. With the publication of Songs of the Sierras, Songs of the Sun-Lands, The Ship in the Desert, and other productions, the critics immediately recognized the genius of the man from whose hand these poems came. In many instances crude, fre- quently unpoetic in the accepted sense, there was nevertheless a distinct individuality about all of his work that marked Joaquin Miller as a literary lion, though strangely enough, it was by England that he was so recognized first, instead of by his homeland. Representative of the marked esteem in which his work is held by collectors, one could cite the figures in book auction records, revealing the sums which have been paid for copies of first editions of his poems and for his autographed letters. Joaquin Miller (christened Cincinnatus Hiner Miller), was born at Liberty, Indiana, on November 10, 1841.l He left his home in Indiana at the age of ten or eleven, with his parents, and never returned to Indiana. He once said that his first impression of life, his first memory, was looking out of a window at a great bon-fire which illuminated the darkness of night with its ruddy glow. -

Lost Silent Feature Films

List of 7200 Lost U.S. Silent Feature Films 1912-29 (last updated 11/16/16) Please note that this compilation is a work in progress, and updates will be posted here regularly. Each listing contains a hyperlink to its entry in our searchable database which features additional information on each title. The database lists approximately 11,000 silent features of four reels or more, and includes both lost films – 7200 as identified here – and approximately 3800 surviving titles of one reel or more. A film in which only a fragment, trailer, outtakes or stills survive is listed as a lost film, however “incomplete” films in which at least one full reel survives are not listed as lost. Please direct any questions or report any errors/suggested changes to Steve Leggett at [email protected] $1,000 Reward (1923) Adam And Evil (1927) $30,000 (1920) Adele (1919) $5,000 Reward (1918) Adopted Son, The (1917) $5,000,000 Counterfeiting Plot, The (1914) Adorable Deceiver , The (1926) 1915 World's Championship Series (1915) Adorable Savage, The (1920) 2 Girls Wanted (1927) Adventure In Hearts, An (1919) 23 1/2 Hours' Leave (1919) Adventure Shop, The (1919) 30 Below Zero (1926) Adventure (1925) 39 East (1920) Adventurer, The (1917) 40-Horse Hawkins (1924) Adventurer, The (1920) 40th Door, The (1924) Adventurer, The (1928) 45 Calibre War (1929) Adventures Of A Boy Scout, The (1915) 813 (1920) Adventures Of Buffalo Bill, The (1917) Abandonment, The (1916) Adventures Of Carol, The (1917) Abie's Imported Bride (1925) Adventures Of Kathlyn, The (1916) Ableminded Lady,