Ina Coolbrith Chit Chat Club

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ina Coolbrith of California's "Overland Trinity95 by BENJAMIN DE CASSERES

Boolcs and the Book World of The Sun, December 7, 1919. 15 Ina Coolbrith of California's "Overland Trinity95 By BENJAMIN DE CASSERES. written, you know. I have just sent down ASTWARD the star of literary cm-- town for one of my books, want 'A J and I pire takes its way. After twenty-liv-e to paste a photograph as well as auto- years Ina Donna Coolbrith, crowned graph in it to mail to you. poet laureate of California by the Panama-P- "The old Oakland literary days! Do acific Exposition, has returned to yon know you were the first. one who ever New York. Her house on Russian Hill, complimented me on my choice of reading San Francisco, the aristocratic Olympus matter? Nobody at home bothered then-hea- of the Musaj of the Pacific slope, stands over what I read. I was an eager, empty. thirsty, hungry little kid and one day It is as though California had closed a k'Prsmmm mm m:mmm at the library I drew out a volume on golden page of literary and artistic mem- Pizzaro in Pern (I was ten years old). ories in her great epic for the life of You got the book and stamped it for me; Miss Coolbrith 'almost spans the life of and as you handed it to me you praised California itself. Her active and acuto me for reading books of that nature. , brain is a storehouse of memories and "Proud ! If you only knew how proud ' anecdote of those who have immortalized your words made me! For I thought a her State in literature Bret Harte, Joa- great deal of you. -

The Outpouring of Support

Sir Harold Evans Sir Harold Evans was the editor of The Sunday Times from 1967 to 1981 and the Times in 1981. From 1990 until 1997, he was the president and publisher of Random House, and later the editorial director for US News and World Report, the New York Daily News, and The Atlantic Monthly. He edited three books by Henry Kissinger, My American Journey by Colin Powell, Game Plan: How to Conduct the U.S. Soviet Contest by Zbiginew Brzezinski; Debt and Danger: The World Economic Crisis by Harold Lever; and The Yom Kippur War by The Insight Team of The Sunday Times. He is additionally the author, in association with Edwin Taylor, of Pictures on a Page. Continuously in print for 37 years, the publication is the culmination of a five-volume series on editing and design featuring interviews by Henri Cartier Bresson, Bert Stern, Harry Benson, Bill Brandt, Eddie Adams, Andre Kertesz, Eugene Smith, and Richard Avedon. Evans' best known work, The American Century, won critical acclaim when published in 1998, staying on the New York Times bestseller list for 10 weeks. The sequel, They Made America (2004), describes the lives of some of the country's most important inventors and innovators, and was named by Fortune as one of the best books in the 75 years of that magazine's publication. The latter was adapted as a four-part television mini-series that same year and as a National Public Radio special in the USA in 2005. sirharoldevans.com Dedicated to the public exploration of the early history of New Amsterdam and New York City April 1, 2020 Hon. -

Contents Part One Page Pioneer Voices

Copyright McClur Co . A . C. g I91 7 em e 1 1 Published N ov b r , 9 7 M . N D L . L . A . L A R . To . M . G J , . TO OTHER FRIENDS I N SANTA BARBARA W HO TAU G HT M E T HE LOVELINESS OF CALIFORNIA CONTENTS P art One PAGE PIONEER VOICES Part T wo VOICES OF THE GREAT SING ERS Part T hree LIVI NG VOICES INTRODUCTION IN PREPARI NG this collection o f verse for publi ha two ! cation , I have d purposes first , to make an — - interesting book the ancient and ever living pur f l e —and pose o al makers O f good literatur second , to give to all who may desire it a volume of poems that sing and celebrate the traditions, the life , and the natural beauty o f one o f the greatest common n r wealths in the union . The roma ce and ha dship, the gayety an d the heroism o f the days o f the padres a and the later pioneers , the adventurous d sh and ’ o f -niners flare the forty , the rich , golden health and prosperity o f all the days that have followed the pioneer period — all these things are most vivid and colorful history an d tradition and have had no smal l part in creating for Californians that heritage o f naive and fierce affection — belligerent devotion to — their commonwealth and its life and customs by which they are known and with which they startle the quieter and cooler hearts o f men and women o f r o f mo e staid and sober states . -

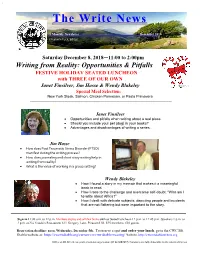

Thee Write News

F TThhee WWrriittee NNeewwss A Monthly Newsletter December 2018 Elisabeth Tuck, editor February 2015 2015 Saturday December 8, 2018—11:00 to 2:00pm Writing from Reality: Opportunities & Pitfalls FESTIVE HOLIDAY SEATED LUNCHEON with THREE OF OUR OWN Janet Finsilver, Jim Hasse & Wendy Blakeley Special Meal Selection: New York Steak, Salmon, Chicken Parmesan, or Pasta Primavera _______________________________________________________________________________________ Janet Finsilver Opportunities and pitfalls when writing about a real place. Should you include your pet (dog) in your books? Advantages and disadvantages of writing a series. Jim Hasse How does Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) manifest during the writing process? How does journaling and short story writing help in writing from reality? What is the value of working in a group setting? Wendy Blakeley How I found a story in my memoir that makes it a meaningful book to read. How I rose to the challenge and overcame self-doubt: "Who am I to write about Africa?" How I dealt with delicate subjects, depicting people and incidents that are not flattering but were important to the story. Sign-in 11:00 a.m. to 12 p.m. Members display and sell their books until our Seated Luncheon 12 p.m. to 12:45 p.m. Speakers 1 p.m. to 2 p.m. at Zio Fraedo’s Restaurant: 611 Gregory Lane, Pleasant Hill. $25 members, $30 guests. Reservation deadline: noon, Wednesday, December 5th. To reserve a spot and order your lunch, go to the CWC Mt. Diablo website at: https://cwcmtdiablo.org/current-cwc-mt-diablo-meeting/ Website, http://cwcmtdiablowriters.org CWC is an IRS 501-c3 non-profit charitable organization (ID 94-6082827). -

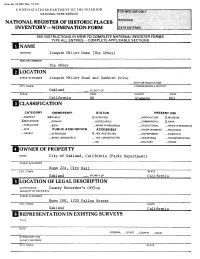

Hclassification

Form No. 10-300 (Rev. 10-74) UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OE THE INTERIOR NATIONAL PARK SERVICE NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES INVENTORY -- NOMINATION FORM SEE INSTRUCTIONS IN HOW TO COMPLETE NATIONAL REGISTER FORMS TYPE ALL ENTRIES -- COMPLETE APPLICABLE SECTIONS [NAME HISTORIC Joaquin Miller Home (The Abbey) AND/OR COMMON The Abbey LOCATION STREETS.NUMBER Joaquin Miller Road and Sanborn Drive _NOT FOR PUBLICATION CITY, TOWN CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT Oakland _.. VICINITY OF STATE CODE COUNTY CODE California 06 AT ameda 001 HCLASSIFICATION CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS PRESENT USE —DISTRICT XXPUBLIC X-OCCUPIED _ AGRICULTURE X_MUSEUM J^BUILDINGIS) —PRIVATE —UNOCCUPIED —COMMERCIAL X_PARK —STRUCTURE —BOTH —WORK IN PROGRESS —EDUCATIONAL —PRIVATE RESIDENCE —SITE PUBLIC ACQUISITION ACCESSIBLE —ENTERTAINMENT —RELIGIOUS —OBJECT _IN PROCESS X-YES: RESTRICTED —GOVERNMENT —SCIENTIFIC —BEING CONSIDERED — YES: UNRESTRICTED —INDUSTRIAL —TRANSPORTATION _NO —MILITARY —OTHER: OWNER OF PROPERTY NAME City of Oakland, California (Parks Department) STREET & NUMBER Room 224, City Hall CITY, TOWN STATE Oakland VICINITY OF California COURTHOUSE, County Recorder ! s Office REGISTRY OF DEEDS,ETC. STREET & NUMBER Room 100^ 1225 Fallen Street CITY. TOWN STATE Oakland California REPRESENTATION IN EXISTING SURVEYS TITLE DATE .FEDERAL _STATE __COUNTY _LOCAL DEPOSITORY FOR SURVEY RECORDS CITY, TOWN DESCRIPTION CONDITION CHECK ONE CHECK ONE —EXCELLENT -DETERIORATED —UNALTERED XXORIGINALSITE _MOVED DATE. X-GOOD _RUINS X_ALTERED _FAIR _UNEXPOSED DESCRIBETHE PRESENT AND ORIGINAL (IF KNOWN) PHYSICAL APPEARANCE The Joaquin Miller House is a small three-part frame building at the foot of the steep hills East of Oakland California. Composed of three single rooms joined together, the so-called "Abbey" must be seen as the most provincial of efforts to impose gothic-revival detail upon the three rooms. -

Chapter 21: Literature: John Muir

Mount Shasta Annotated Bibliography Chapter 21 Literature: John Muir John Muir's exceptional mental and physical stamina enabled him to rigorously pursue, often in solitary fashion, the exploration of California's mountains. In the Fall of 1874 and the Spring of 1875 he climbed Mt. Shasta three times. Among the entries listed in this section are Muir's pocket notebooks kept during these climbs. His 1875 notebook contains many detailed drawings of the Shasta region. In one case, on April 28, 1875, he drew from the summit of Mt. Shasta a picture depicting an approaching storm, a storm similar to the one which would two days later, on another climb of the mountain, trap him and his climbing partner Jerome Fay on the summit of Mt. Shasta. Also listed in this section are the reports of A. F. Rodgers, who had hired Muir and Fay in the Spring of 1875 to go and take summit barometric readings. Rodgers wrote a fascinating report which vividly details the appearance and condition of Muir and Fay immediately following the overnight ordeal on April 30, 1875. Muir himself wrote stories of the ordeal that were published in several sources, including Harper's Magazine in 1877 and Picturesque California in 1888. Many of Muir's other published works describe Mt. Shasta. His earliest Mt. Shasta writings were a series of five articles printed in the San Francisco Daily Evening Bulletin in 1874 and 1875; these have been edited and published by Robert Engberg as part of John Muir: Summering in the Sierra (not the same book as Muir's own book My First Summer in the Sierra). -

The American Side of the Line: Eagle City's Origins As an Alaska Gold Rush Town As

THE AMERICAN SIDE OF THE LINE Eagle City’s Origins as an Alaskan Gold Rush Town As Seen in Newspapers and Letters, 1897-1899 National Park Service Edited and Notes by Chris Allan THE AMERICAN SIDE OF THE LINE Eagle City’s Origins as an Alaskan Gold Rush Town National Park Service Yukon-Charley Rivers National Preserve 2019 Acknowledgments I want to thank the staff of the Alaska State Library’s Historical Collections, the University of Alaska Fairbanks’s Alaska and Polar Regions Collections & Archives, the University of Washington’s Special Collections, and the Eagle Historical Society for caring for and making available the photographs in this volume. For additional copies contact: Chris Allan National Park Service 4175 Geist Road Fairbanks, Alaska 99709 Printed in Fairbanks, Alaska February 2019 Front Cover: Buildings in Eagle’s historic district, 2007. The cabin (left) dates from the late 1890s and features squared-off logs and a corrugated metal roof. The red building with clapboard siding was originally part of Ft. Egbert and was moved to its present location after the fort was decommissioned in 1911. Both buildings are owned by Dr. Arthur S. Hansen of Fairbanks. Photograph by Chris Allan, used with permission. Title Page Inset: Map of Alaska and Canada from 1897 with annotations in red from 1898 showing gold-rich areas. Note that Dawson City is shown on the wrong side of the international boundary and Eagle City does not appear because it does not yet exist. Courtesy of Library of Congress (G4371.H2 1897). Back Cover: Miners at Eagle City gather to watch a steamboat being unloaded, 1899. -

Numbers 1 & 2 Spring & Fall 2008

Jeffers Studies Volume 12 Numbers 1 & 2 Spring & Fall 2008 A Double Issue Including a Special Section of Early and Unpublished Work Contents Editor’s Note iii Articles Kindred Poets of Carmel: The Philosophical and Aesthetic Affinities of George Sterling and Robinson Jeffers John Cusatis 1 The Ghost of Robinson Jeffers Temple Cone 13 Jeffers’s Isolationism Robert Zaller 27 Special Section of Early and Unpublished Work The Collected Early Verse of Robinson Jeffers: A Supplement Robert Kafka 43 Haunted Coast Dirk Aardsma, Transcriber and Editor 57 Book Review The Collected Letters of Robinson Jeffers with Selected Letters of Una Jeffers, Volume One, 1890 –1930 Reviewed by Gere S. diZerega, M.D. 77 News and Notes 93 Contributors 99 Cover photo: Robinson Jeffers and George Sterling, c. 1926. Courtesy Jeffers Literary Properties. George Hart Editor’s Note This double issue of volume 12 of Jeffers Studies continues our commit- ment to present readers with original Jeffers material—photos, drafts, unpublished and obscure work, and so on—that will aid and enhance scholarship and interest readers in general. The special section in this volume contains two such items: a supplement to The Collected Early Verse and a transcription of an unpublished manuscript from Occidental College’s Jeffers collection. Robert Kafka has unearthed eight poems from Jeffers’s early years that have never before been collected. Four of the poems originally appeared in The Los Angeles Times, and the other four were included in correspondence or uncatalogued archival collec- tions. One manuscript was given to a one-time girlfriend, and we are happy to reproduce an image of it and a photo of the young lady, Vera Placida Gardner. -

Public Opinion and News Reporting: Different Viewpoints, Changing Perspectives

Public Opinion and News Reporting: Different Viewpoints, Changing Perspectives Grades: 7-HS Subjects: History, Oregon History, Civics, Social Studies Suggested Time Allotment: 1-2 class periods Lesson Background: Our impressions of events can often be influenced by the manner in which they are reported to us in the media. Begin by staging a class discussion of some recent news event(s) that have caused controversy. Can the students think of any news stories that strongly divide public opinions? Any that have been reported in a variety of different ways, depending on which television channels you watch or magazines you read? Can they think of examples where they thought one way or formed a certain opinion about a certain news event, only to have their minds change and opinion shift later, when more information came to light in the media? Moving on from this discussion, the lesson can demonstrate these issues of perspective. Lesson #1: Joaquin Miller—Genius or Cad? Joaquin Miller was the pen name of Cincinnatus Heine Miller, a colorful and controversial poet of the nineteenth century. (Read a detailed biography of Joaquin Miller on Wikipedia, here.) Known in his day as the ‘Poet of the Sierras,’ the ‘Byron of the Rockies,’ and the ‘Bard of Oregon,’ Miller became a celebrity throughout the United States, and especially in England. He was an associate of such enduring literary figures as Ambrose Bierce and Brett Hart. However, it could be argued that Miller’s fame came more from the popular image he created for himself—frontiersman, outdoorsman—than from the actual quality of his literary work. -

6 My Bright Abyss: Thoughts on Modern Belief 34 Why Science

EXPLORING THE INTEGRATION OF FAITH, JUSTICE, AND THE INTELLECTUAL LIFE IN JESUIT, CATHOLIC explore HIGHER EDUCATION P UBLISHED BY THE I GNATIAN C ENTER AT S ANTA C LARA U NIVERSITY SPRING 2014 VOL. 17 6 My Bright Abyss: 18 Why Is God for 34 Why Science 46 The Fragility Thoughts on Christians Good Needs God of Faith Modern Belief for Nothing? Published by the Ignatian Center for Jesuit Education at Santa Clara University SPRING 2014 EXPLORING THE INTEGRATION OF FAITH, JUSTICE, AND THE INTELLECTUAL LIFE IN JESUIT, CATHOLIC HIGHER EDUCATION Michael C. McCarthy, S.J. ’87 Executive Director Theresa Ladrigan-Whelpley Editor Elizabeth Kelley Gillogly ’93 Managing Editor Amy Kremer Gomersall ’88 Design Ignatian Center Advisory Board Margaret Taylor, Chair Katie McCormick Gerri Beasley Charles Barry Dennis McShane, M.D. Patti Boitano Russell Murphy Jim Burns Mary Nally Ternan Simon Chin Saasha Orsi 4 Dialogue and Depth: Nicole Clawson William Rewak, S.J. Michael Engh, S.J. Exploring What Good Is God? Jason Rodriguez Frederick Ferrer Richard Saso Introduction to Spring 2014 explore Javier Gonzalez Robert Scholla, S.J. Michael Hack BY THERESA LADRIGAN-WHELPLEY Gary Serda Catherine Horan-Walker Catherine Wolff Tom Kelly Michael Zampelli, S.J. Michael McCarthy, S.J. 6 My Bright Abyss: Thoughts on Modern Belief explore is published once per year by the Ignatian Center for Jesuit Education at Santa Clara University, BY CHRISTIAN WIMAN 500 El Camino Real, Santa Clara, CA 95053-0454. 408-554-6917 (tel) 408-551-7175 (fax) www.scu.edu/ignatiancenter 10 On Modern Faith: “Out of the The views expressed in explore do not necessarily represent the views of the Ignatian Center. -

Jack London Collection

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/tf8q2nb2xs No online items Inventory of the Jack London Collection Processed by The Huntington Library staff; machine-readable finding aid created by Gabriela A. Montoya Manuscripts Department The Huntington Library 1151 Oxford Road San Marino, California 91108 Phone: (626) 405-2203 Fax: (626) 449-5720 Email: [email protected] URL: http://www.huntington.org/huntingtonlibrary.aspx?id=554 © 1998 The Huntington Library. All rights reserved. Inventory of the Jack London 1 Collection Inventory of the Jack London Collection The Huntington Library San Marino, California Contact Information Manuscripts Department The Huntington Library 1151 Oxford Road San Marino, California 91108 Phone: (626) 405-2203 Fax: (626) 449-5720 Email: [email protected] URL: http://www.huntington.org/huntingtonlibrary.aspx?id=554 Processed by: David Mike Hamilton; updated by Sara S. Hodson Date Completed: July 1980; updated May 1993 Encoded by: Gabriela A. Montoya © 1998 The Huntington Library. All rights reserved. Descriptive Summary Title: Jack London Collection Creator: London, Jack, 1876-1916 Extent: 594 boxes Repository: The Huntington Library San Marino, California 91108 Language: English. Access Collection is open to qualified researches by prior application through the Reader Services Department. For more information please go to following URL. Publication Rights In order to quote from, publish, or reproduce any of the manuscripts or visual materials, researchers must obtain formal permission from the office of the Library Director. In most instances, permission is given by the Huntington as owner of the physical property rights only, and researchers must also obtain permission from the holder of the literary rights In some instances, the Huntington owns the literary rights, as well as the physical property rights. -

George Sterling Papers M0021

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/tf8m3nb3dv No online items Guide to the George Sterling Papers M0021 Department of Special Collections and University Archives 1999, revised 2017 Green Library 557 Escondido Mall Stanford 94305-6064 [email protected] URL: http://library.stanford.edu/spc Guide to the George Sterling M0021167 1 Papers M0021 Language of Material: English Contributing Institution: Department of Special Collections and University Archives Title: George Sterling papers source: Blaettler, Rudolph source: Bynner, Witter source: Bender, Albert M. (Albert Maurice), 1866-1941 Creator: Sterling, George, 1869-1926 Identifier/Call Number: M0021 Identifier/Call Number: 167 Physical Description: 1 Linear Feet(2 boxes) Date (inclusive): 1909-1942 Date (bulk): 1920-1926 Abstract: George Sterling (1869–1926) was an American writer, poet and playwright based in the San Francisco, California Bay Area. Immediate Source of Acquisition The majority of the Sterling papers came to Stanford as a gift of Rudolf Blaettler, collector. The Bynner-Sterling correspondence is a gift of Witter Bynner. (Oct 1960) Biographical / Historical American poet and playwright George Sterling was born in Sag Harbor, N.Y. on December 1, 1869. He was educated on the East Coast and attended St. Charles College in Maryland. In 1896 he married Carrie Rand of Oakland, California, and from 1898 to 1908 he was private secretary to Frank C. Havens of that city. Sterling's first volume of poems, " Testimony of the Suns and Other Poems, was published in 1903. After that time, there were nine other volumes and a number of separate poems published. From 1908 to 1915, Sterling was one of the leaders of the artist colony at Carmel, California.