D2.1: Draft Extended Data Policy Framework for Photon and Neutron Ris

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

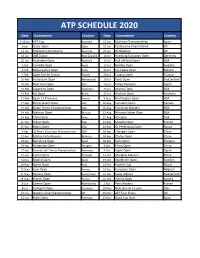

Atp Schedule 2020

ATP SCHEDULE 2020 Date Tournament Country Date Tournament Country 3-12-Jan ATP Cup Australia 22-Jun Mallorca Championships Spain 6-Jan Qatar Open Qatar 22-Jun Eastbourne International UK 13-Jan Adelaide International Australia 29-Jun Wimbledon UK 13-Jan ASB Classic New Zealand 13-Jul Hamburg European Open Germany 20-Jan Australian Open Australia 13-Jul Hall of Fame Open USA 3-Feb Cordoba Open Spain 13-Jul Nordea Open Sweden 3-Feb Maharashtra Open India 20-Jul Los Cabos Open Mexico 3-Feb Open Sud de France France 20-Jul Croatia Open Croatia 10-Feb Rotterdam Open Netherlands 20-Jul Swiss Open Switzerland 10-Feb New York Open USA 25-Jul Tokyo Olympics Japan 10-Feb Argentina Open Argentina 27-Jul Atlanta Open USA 16-Feb Rio Open Brazil 27-Jul Austrian Open Australia 17-Feb Open 13 Provence France 2-Aug Washington Open USA 17-Feb Delray Beach Open USA 10-Aug Canadian Open Canada 24-Feb Dubai Tennis Championships UAE 16-Aug Cincinnati Masters USA 24-Feb Mexican Open Mexico 23-Aug Winston-Salem Open USA 24-Feb Chile Open Chile 31-Aug US Open USA 12-Mar Indian Wells USA 21-Sep Moselle Open France 25-Mar Miami Open USA 21-Sep St. Petersburg Open Russia 6-Apr US Men's Clay Court Championships USA 28-Sep Chengdu Open China 12-Apr Monte Carlo Masters Monaco 28-Sep Zhuhai Open China 20-Apr Barcelona Open Spain 28-Sep Sofia Open Bulgaria 20-Apr Hungarian Open Hungary 5-Oct China Open China 27-Apr Bavarian Int'l Tennis Championships Germany 5-Oct Japan Open Japan 27-Apr Estoril Open Portugal 11-Oct Shanghai Masters China 3-May Madrid Open Spain 19-Oct Stockholm Open Sweden 10-May Italian Open Italy 19-Oct Kremlin Cup Russia 17-May Lyon Open France 19-Oct European Open Belgium 17-May Geneva Open Switzerland 26-Oct Swiss Indoors Switzerland 24-May French Open France 26-Oct Vienna Open Austria 8-Jun Libema Open Netherlands 2-Nov Paris Masters France 8-Jun Stuttgart Open Germany 10-Nov Next Gen ATP Finals Italy 15-Jun Queen's Club Championships UK 15-Nov ATP Tour Finals UK 15-Jun Halle Open Germany 23-Nov Davis Cup final Spain. -

PSG Storm Into Maiden Final REUTERS – LISBON

SPORT SPORT | 18 SPORT | 19 England captain Lukaku, Martinez Joe Root ‘would fire five-star Inter love’ to tour into Europa Pakistan League final WEDNESDAY 19 AUGUST 2020 Champions League: Di Maria shines as Parisians crush Leipzig 3-0 PSG storm into maiden final REUTERS – LISBON Paris Saint-Germain reached their first ever Champions League final with a 3-0 win over RB Leipzig yesterday, inspired by Argentine Angel Di Maria. Goals from Marquinhos and Di Maria put PSG 2-0 up at the interval and Juan Bernat added the third in the 56th minute for what was a comfortable victory at the Estadio da Luz. The French club, who celebrating the 50th anniversary of their founding in 1970, will meet the winner of Wednes- day's other semi between Bayern Munich and Olympique Lyonnais. The big-spending PSG were a step too far for Leipzig, who were playing in the regional leagues just 11 years ago and have outperformed all expectations by reaching the last four. With French World Cup winning forward Kylian Mbappe back in the starting line-up after fully recovering from his ankle injury, PSG's German coach Thomas Tuchel was able to field his preferred attacking trident with Bra- zilian Neymar and Di Maria. Right from the outset, PSG looked a Paris Saint-Germain’s Brazilian defender Marquinhos heads the ball and scores during the UEFA Championspions threat to the Leipzig defence with League semi-final against Leipzig at the Luz stadium in Lisbon, yesterday. Neymar clipping the post after he was slipped in by Mbappe in the sixth minute. -

Spain Entrepreneurial Nation Strategy 36 2.4

Spain Entrepreneurial Nation June 2021 Cover photo: David Gavi in Unsplash Document developed by: Foreword by the President of the Government 7 1. Executive Summary 13 2. En-route towards an Entrepreneurial Nation 25 2.1. Productivity Challenge as a Guarantee of Resillience when Facing a Crisis 27 2.2. A National Mission 34 2.3. The Spain Entrepreneurial Nation Strategy 36 2.4. An Invitation 42 3. Situation analysis and diagnosis 45 3.1. The Goals 48 3.1.1. The Investment Goal 49 3.1.2. The Talent Goal 51 3.1.3. The Scalability Goal 54 3.1.4. The Entrepreneurial Public Sector Goal 56 3.2. Driving Sectors 58 3.2.1. Industry 60 3.2.2. Tourism and culture 62 3.2.3. Movility 64 3.2.4. Health 66 3.2.5. Construction and Materials 67 3.2.6. Energy and Ecological Transition 68 3.2.7. Banking and Finance 69 3.2.8. Digital and Telecommunications 70 3.2.9. Agroindustry 71 3.2.10. Biotechnology 72 3.3. The Gaps 74 3.3.1. The Gender Gap 76 3.3.2. The Territorial Gap 78 3.3.3. The Socioeconomic Gap 80 3.3.4. The Generational Gap 82 4. Strategic Measures for Spain Entrepreneurial Nationa 85 4.1. Priority Measures 88 4.2. Investment 98 4.3. Entrepreneurial Public Sector 108 4.4. Scalability 114 4.4. Talent 120 5. How to Contribute to the Mission: Spain Entrepreneurial Nation 131 6. The Key Figures behind an Entrepreneurial Nation 137 6.1. -

2020-Atp-Calendar.Pdf

2020 SEASON Week Start Date City Current Tournament Name Surface Draw 1 Jan 3 Brisbane, Perth, Sydney ⁶ ATP Cup H 24 Teams Jan 6 Doha ⁸ Qatar ExxonMobil Open H 28 2 Jan 13 Adelaide ⁸ Adelaide International H 28 Jan 13 Auckland ⁸ ASB Classic H 28 3 Jan 20 Melbourne H Australian 128 Open* H 128 4 5 Feb 3 Córdoba Córdoba Open CL 28 Feb 3 Montpellier Open Sud de France IH 28 Feb 3 Pune Tata Open Maharashtra H 28 6 Feb 10 Rotterdam ABN AMRO World Tennis Tournament IH 32 Feb 10 Buenos Aires Argentina Open CL 28 Feb 10 New York New York Open IH 28 7 Feb 17 Rio de Janeiro Rio Open presented by Claro CL 32 Feb 17 Delray Beach Delray Beach Open by VITACOST.com H 32 Feb 17 Marseille Open 13 Provence IH 28 8 Feb 24 Acapulco ⁸ Abierto Mexicano Telcel presentado por HSBC H 32 Feb 24 Dubai ⁸ Dubai Duty Free Tennis Championships H 32 Feb 24 São Paulo Brasil Open ICL 28 9 Mar 6 Davis Cup Qualifiers* 10 Mar 12 Indian Wells ⁵ BNP Paribas Open H 96 11 12 Mar 25 Miami ⁴ Miami Open presented by Itaú H 96 13 14 Apr 6 Houston Fayez Sarofim & Co. U.S. Men’s Clay Court Championship CL 28 Apr 6 Marrakech Grand Prix Hassan II CL 32 15 Apr 12 Monte-Carlo ¹ Rolex Monte-Carlo Masters CL 56 16 Apr 20 Barcelona Barcelona Open Banc Sabadell CL 48 Apr 20 Budapest Hungarian Open CL 28 17 Apr 27 Estoril Millennium Estoril Open CL 28 Apr 27 Munich BMW Open by FWU CL 28 18 May 3 Madrid ¹ Mutua Madrid Open CL 56 19 May 10 Rome ¹ Internazionali BNL d’Italia CL 56 20 May 17 Geneva ¹ ˒ ⁸ Banque Eric Sturdza Geneva Open CL 28 May 17 Lyon ¹ ˒ ⁸ Open Parc Auvergne-Rhône-Alpes Lyon CL 28 21 May 24 Paris ¹ H Roland 128 Garros* CL 128 22 23 Jun 8 ’s-Hertogenbosch Libema Open G 28 Jun 8 Stuttgart MercedesCup G 28 24 Jun 15 Halle 28. -

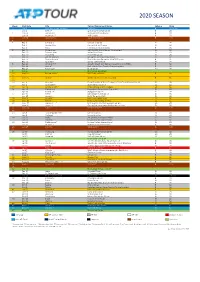

Atp Tour2020 Season

ATP TOUR 2020 SEASON As of 2 December 2019 WEEK START DATE CITY TOURNAMENT NAME SURFACE DRAW 1 3 JAN BRISBANE, PERTH, SYDNEY 6 ATP Cup H 24 Teams 6 JAN DOHA 8 Qatar ExxonMobil Open H 28 2 13 JAN ADELAIDE 1, 8 Adelaide International H 28 13 JAN AUCKLAND 8 ASB Classic H 28 3 20 JAN MELBOURNE Australian Open* H 128 4 5 3 FEB CORDOBA Cordoba Open CL 28 3 FEB MONTPELLIER Open Sud de France IH 28 3 FEB PUNE Tata Open Maharashtra H 28 6 10 FEB ROTTERDAM ABN AMRO World Tennis Tournament IH 32 CALENDAR 2020 10 FEB BUENOS AIRES Argentina Open CL 28 10 FEB NEW YORK New York Open IH 28 7 17 FEB RIO DE JANEIRO Rio Open presented by Claro CL 32 17 FEB DELRAY BEACH Delray Beach Open by VITACOST.com H 32 17 FEB MARSEILLE Open 13 Provence IH 28 8 24 FEB ACAPULCO 8 Abierto Mexicano Telcel presentado por HSBC H 32 24 FEB DUBAI 8 Dubai Duty Free Tennis Championships H 32 24 FEB SANTIAGO Chile Open CL 28 9 6 MAR Davis Cup Qualifiers* 10 12 MAR INDIAN WELLS 5 BNP Paribas Open H 96 11 12 25 MAR MIAMI 4 Miami Open presented by Itau H 96 13 14 6 APR HOUSTON Fayez Sarofim & Co. U.S. Men’s Clay Court Championship CL 28 6 APR MARRAKECH Grand Prix Hassan II CL 32 15 12 APR MONTE CARLO 1 Rolex Monte-Carlo Masters CL 56 16 20 APR BARCELONA Barcelona Open Banc Sabadell CL 48 20 APR BUDAPEST Hungarian Open CL 28 17 27 APR ESTORIL Millennium Estoril Open CL 28 27 APR MUNICH BMW Open by FWU CL 28 18 3 MAY MADRID 1 Mutua Madrid Open CL 56 19 10 MAY ROME 1 Internazionali BNL d’Italia CL 56 20 17 MAY GENEVA 1, 8 Banque Eric Sturdza Geneva Open CL 28 17 MAY LYON 1, 8 Open -

The Economic Impact of Open Data Opportunities for Value Creation in Europe the ECONOMIC IMPACT of OPEN DATA

EUROPEAN DATA PORTAL The Economic Impact of Open Data Opportunities for value creation in Europe THE ECONOMIC IMPACT OF OPEN DATA This study has been prepared by Capgemini Invent as part of the European Data Portal. The European Data Portal is an initiative of the European Commission, implemented with the support of a consortium led by Capgemini Invent, including Intrasoft International, Fraunhofer Fokus, con.terra, Sogeti, 52North, Time.Lex, the Lisbon Council, and the University of Southampton. The Publications Office of the European Union is responsible for contract management of the European Data Portal. For more information about this paper, please contact: European Commission Directorate General for Communications Networks, Content and Technology Unit G.1 Data Policy and Innovation Daniele Rizzi – Policy Officer Email: [email protected] European Data Portal Gianfranco Cecconi, European Data Portal Lead Email: [email protected] Written by: Esther Huyer Email: [email protected] Laura van Knippenberg Email: [email protected] With contributions by: Eline Lincklaen Arriëns Marit Blank Last update: 26.01.2020 www: https://europeandataportal.eu/ @: [email protected] PDF ISBN: 978-92-78-42108-3 doi: 10.2830/63132 OA-04-20-043-EN-N © European Union, 1998-2020 The Commission’s document reuse policy is based on Decision 2011/833/EU. Except where otherwise stated, the editorial content of this website is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International licence. This means that you can reuse this content provided you acknowledge the source and indicate any changes you have made. To use or reproduce content not owned by the EU, you may need to seek permission directly from the rights holders. -

February 2020

FEBRUARY 2020 President Cecilie McIntyre [email protected] Page 1-3 IC Morning Teas 7 ASB Classic Weeks. th Hon Sec. Angela Hart [email protected] Page 3 Date for 2020 AGM & Dinner 17 May Page 4 ACE Philanthropy Programme Update Vice President Russell Tills [email protected] Page 5 Blast From The Past Judy Tinnock Hon Treasurer Chris Ronayne [email protected] Page 6 Possible future of Classic Men’s Week Link to IC Council website www.ictennis.net Page 7 Julian Tatum Rod Laver Junior Challenge Have a look through this website and click the flags to see news of the other countries. Page 8-12 Drop Shots Morning and afternoon teas. We have continued our tradition of inviting all IC Members and a guest to our teas, held on both Mondays of the International Men's and Women’s Tournaments. Thanks to Tennis Auckland for the ticket arrangements. The photos are available to all who wish to see them on our Cluster link. https://cluster.co/i/XVX3DXDD We had around 70 at each and all enjoyed catching up with their tennis friends. The new Members introduced were Julie Turner, Robin Denton, and Hon Members Peter Kiely and Tony Woolf , here with ICNZ President Cecilie McIntyre. Thanks to those who came from around the country to join in. As you will see ( on Page 2 ) one of the new Members invited, Troy Tipene was unable to be with us, as he was starting a new job but his message was read out and commented on favourably by many. -

CESSDA Strengthening and Widening

Ref. Ares(2017)4265698 - 31/08/2017 Research and Innovation Action CESSDA Strengthening and Widening Project Number: 674939 Start Date of Project: 01/08/2015 Duration: 27 months Deliverable 3.6 Final integrated audit report Dissemination Level Public Due Date of Deliverable 31/07/2017 Actual Submission Date 31/08/2017 Work Package WP 3 Task 3.2 Type Report EC Approval Status 16 November 2017 Version V1.4 Number of Pages p.1 – p.69 Abstract: This is a follow-up of D3.2 County report. Focus is on identifying what development steps can be proposed to tackle the obstacles in the way of achieving the widened and strengthened CESSDA ERIC. The maturity of data archive service (DAS) in most European countries was audited. The analysis contains elements of the wider data sharing ecosystem. The information in this document reflects only the author’s views and the European Community is not liable for any use that may be made of the information contained therein. The information in this document is provided “as is” without guarantee or warranty of any kind, express or implied, including but not limited to the fitness of the information for a particular purpose. The user thereof uses the information at his/ her sole risk and liability. 1 D3.6 – v. 1.4 History Version Date Reason Revised by 0.1 30/04/2017 First draft results chapters Task leader Subtasks lead 0.2 16/06/2017 Editorial review partners 0.3 23/06/2017 Final integral version Task leader IEN, FFZG, 0.4 3/07/2017 WP leader and subtasks lead partners approval FORS, NSD, SND, UKDA 1.0 7/07/2017 -

Final Report Providing Policy-Relevant Comparative Analysis on the Subject Matter

MORE4 study Support data collection and analysis concerning mobility patterns and career paths of researchers PPMI, IDEA Consult and WIFO February 2021 MORE4 study: Support data collection and analysis concerning mobility patterns and career paths of researchers European Commission Directorate-General for Research & Innovation Directorate A — Directorate A — ERA & Innovation Unit A.3 — R&I Actors and Research Careers Email: [email protected] [email protected] European Commission B-1049 Brussels Manuscript completed in February 2021. This document has been prepared for the European Commission, however, it reflects the views only of the authors, and the European Commission is not liable for any consequence stemming from the reuse of this publication. More information on the European Union is available on the internet (http://europa.eu). PDF ISBN 978-92-76-34099-7 doi: 10.2777/645537 KI-02-21-455-EN-N Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union, 2021 © European Union, 2021 The reuse policy of European Commission documents is implemented based on Commission Decision 2011/833/EU of 12 December 2011 on the reuse of Commission documents (OJ L 330, 14.12.2011, p. 39). Except otherwise noted, the reuse of this document is authorised under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International (CC-BY 4.0) licence (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/). This means that reuse is allowed provided appropriate credit is given and any changes are indicated. For any use or reproduction of elements that are not owned by the European Union, permission may need to be sought directly from the respective right holders. -

Research Data Framework (Rdaf): Motivation, Development, and a Preliminary Framework Core

NIST Special Publication 1500-18 Research Data Framework (RDaF): Motivation, Development, and A Preliminary Framework Core Robert J. Hanisch Debra L. Kaiser Bonnie C. Carroll This publication is available free of charge from: https://doi.org/10.6028/NIST.SP.1500-18 NIST Special Publication 1500-18 Research Data Framework (RDaF): Motivation, Development, and A Preliminary Framework Core Robert J. Hanisch Debra L. Kaiser Office of Data and Informatics Material Measurement Laboratory Bonnie C. Carroll Consultant Information International Associates Oak Ridge, TN This publication is available free of charge from: https://doi.org/10.6028/NIST.SP.1500-18 February 2021 U.S. Department of Commerce Wynn Coggins, Acting Secretary National Institute of Standards and Technology James K. Olthoff, Performing the Non-Exclusive Functions and Duties of the Under Secretary of Commerce for Standards and Technology & Director, National Institute of Standards and Technology Certain commercial entities, equipment, or materials may be identified in this document in order to describe an experimental procedure or concept adequately. Such identification is not intended to imply recommendation or endorsement by the National Institute of Standards and Technology, nor is it intended to imply that the entities, materials, or equipment are necessarily the best available for the purpose. Publications in the SP1500 subseries are intended to capture external perspectives related to NIST standards, measurement, and testing-related efforts. These external perspectives can come from industry, academia, government, and others. These reports are intended to document external perspectives and do not represent official NIST positions. The opinions, recommendations, findings, and conclusions in this publication do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of NIST or the United States Government. -

2020 PO Box 302-145 North Harbour, Auckland 0751

TENNIS NZ Te Pūrongo a Tēnehi Aotearoa Tennis New Zealand AUT Millennium, 17 Antares Place, Rosedale 0632 2019-2020 PO Box 302-145 North Harbour, Auckland 0751 P: +64 9 528 5428 E: [email protected] TENNIS NZ ANNUAL REPORT 2019-2020 Ngā Kaupapa Matua BOARD CHAIR & CEO REPORT 5 ENABLE 7 WIN 17 SECURE 21 AFFILIATE REPORTS 25 AWARDS 33 RESULTS & RANKINGS 35 GOVERNANCE 43 FINANCIAL 45 DRIVE 60 OUR MISSION BUILDING COMMUNITY THROUGH TENNIS OUR VISION TENNIS - ACCESSIBLE AND THRIVING 3 4 TENNIS NZ ANNUAL REPORT 2019-2020 2019/2020 has been a year of stretch and challenge. The Coach Development team continued to develop We began the 2020 year positively, by delivering There have been some staff changes through this Throughout 2019 we planned for and delivered one the Coach Develoment Framework further by the largest calendar of summer events we have year. We farewelled Simon Rea as High Performance of our most ambitious years of programmes and offering the first Club Pro course since 2014 and attempted in many years. However only 17 days Director and our National Coach Christophe tournaments. offering more modular opportunities as requested after completing the Davis Cup Tie in Auckland, New Lambert stepped up to replace him. Patrick Landy from participant feedback. Workshops continue Zealand went into Level 4 lockdown. Due to having (Coach Development Manager) returned to his The strategic focus has continued to be framed by to be offered throughout the country to enable completed most of our summer season and the home country of Australia and Gayle Vaughan was our three key pillars of enable, win and secure. -

Self-Assessment DANS for Periodic Evaluation of the Institute

Self-assessment DANS for periodic evaluation of the institute Version 1.7 06-10-2017 Content Preface: DANS and the Standard Evaluation Protocol ................................................. 2 Introduction ......................................................................................................... 3 1. Organisation .................................................................................................... 4 1.1. Mission .................................................................................................. 4 1.2. Governance ............................................................................................ 4 1.3. Composition and staff .............................................................................. 5 1.4. Finances ................................................................................................ 5 1.5. Organisation development ........................................................................ 5 2. Strategy .......................................................................................................... 7 3. Results achieved in the past six years (2011-2016) ............................................... 8 3.1 Quality of DANS research data services ...................................................... 8 3.2 Scientific quality of research at DANS ....................................................... 10 3.3 PhD students ........................................................................................ 10 3.4 Relevance to society .............................................................................