Plot Archetypes in Robert Schumann's Piano Quintet and Piano Quartet Emily S

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Wind, String, & Mixed Chamber Groups

WIND, STRING, & MIXED CHAMBER GROUPS - SPRING 2019 (v 2.1) - including piano, harp, and percussion - PLEASE read the “Rules of the Road” for chamber music on the “performance” section of INSIDE MUSIC on the School of Music website: https://www.cmu.edu/cfa/music/current-students/ensembles/chamber-music.html Each group should select/elect/draft a “contact person” and submit that person’s name to the chamber music Graduate Assistant, Yalyen Savignon: [email protected] Please note that this is the second draft of the roster. All registered students have been placed, and all requests have been fulfilled. We hope that few if any further changes will need to be made. Remember, other students’ education depends on your being a reliable member of your group! IF YOU SPOT MISTAKES ON THIS LIST, PLEASE CONTACT PROF. WHIPPLE. RJW and CW, February 6, 2019 57-228 OR 57-928 SEXTETS sec A - WIND & PIANO SEXTET Alisa Smith, flute Elizabeth Mountz, oboe Elizabeth Carney, clarinet Ji Won Song, horn Andrew Hahn, bassoon Winfred Wang, piano coaches: R. James Whipple QUINTETS sec B - GRADUATE WIND QUINTET Theresa Abalos, flute Evan Tegley, oboe Alex Athitakas, clarinet Diana McLaughlin, horn Nicholas Evans, bassoon coach: Thomas Thompson sec C - “VENTUS FERRO” TBA, flute Alicia Smith, oboe Zack Neville, clarinet Ziming Zhu, horn Dreya Cherry, bassoon coach: James Gorton sec D - PROKOFIEV: Quintet in g minor Christian Bernard, oboe Bryce Kyle, clarinet TBA, violin Angela-Maureen Zollman, viola Mark Stroud, bass coach: James Gorton STRING QUARTETS 57-226 OR 57-926 1. Jasper Rogal, violin Noah Steinbaum, violin Angela Rubin,viola Kyle Johnson, cello coach: Cyrus Forough 2. -

574040-41 Itunes Beethoven

BEETHOVEN Chamber Music Piano Quartet in E flat major • Six German Dances Various Artists Ludwig van ¡ Piano Quartet in E flat major, Op. 16 (1797) 26:16 ™ I. Grave – Allegro ma non troppo 13:01 £ II. Andante cantabile 7:20 BEE(1T77H0–1O827V) En III. Rondo: Allegro, ma non troppo 5:54 1 ¢ 6 Minuets, WoO 9, Hess 26 (c. 1799) 12:20 March in D major, WoO 24 ‘Marsch zur grossen Wachtparade ∞ No. 1 in E flat major 2:05 No. 2 in G major 1:58 2 (Grosser Marsch no. 4)’ (1816) 8:17 § No. 3 in C major 2:29 March in C major, WoO 20 ‘Zapfenstreich no. 2’ (c. 1809–22/23) 4:27 ¶ 3 • No. 4 in F major 2:01 4 Polonaise in D major, WoO 21 (1810) 2:06 ª No. 5 in D major 1:50 Écossaise in D major, WoO 22 (c. 1809–10) 0:58 No. 6 in G major 1:56 5 3 Equali, WoO 30 (1812) 5:03 º 6 Ländlerische Tänze, WoO 15 (version for 2 violins and double bass) (1801–02) 5:06 6 No. 1. Andante 2:14 ⁄ No. 1 in D major 0:43 No. 2 in D major 0:42 7 No. 2. Poco adagio 1:42 ¤ No. 3. Poco sostenuto 1:05 ‹ No. 3 in D major 0:38 8 › No. 4 in D minor 0:43 Adagio in A flat major, Hess 297 (1815) 0:52 9 fi No. 5 in D major 0:42 March in B flat major, WoO 29, Hess 107 ‘Grenadier March’ No. -

Harmonic Organization in Aaron Copland's Piano Quartet

37 At6( /NO, 116 HARMONIC ORGANIZATION IN AARON COPLAND'S PIANO QUARTET THESIS Presented to the Graduate Council of the University of North Texas in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF MUSIC By James McGowan, M.Mus, B.Mus Denton, Texas August, 1995 37 At6( /NO, 116 HARMONIC ORGANIZATION IN AARON COPLAND'S PIANO QUARTET THESIS Presented to the Graduate Council of the University of North Texas in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF MUSIC By James McGowan, M.Mus, B.Mus Denton, Texas August, 1995 K McGowan, James, Harmonic Organization in Aaron Copland's Piano Quartet. Master of Music (Theory), August, 1995, 86 pp., 22 examples, 5 figures, bibliography, 122 titles. This thesis presents an analysis of Copland's first major serial work, the Quartet for Piano and Strings (1950), using pitch-class set theory and tonal analytical techniques. The first chapter introduces Copland's Piano Quartet in its historical context and considers major influences on his compositional development. The second chapter takes up a pitch-class set approach to the work, emphasizing the role played by the eleven-tone row in determining salient pc sets. Chapter Three re-examines many of these same passages from the viewpoint of tonal referentiality, considering how Copland is able to evoke tonal gestures within a structural context governed by pc-set relationships. The fourth chapter will reflect on the dialectic that is played out in this work between pc-sets and tonal elements, and considers the strengths and weaknesses of various analytical approaches to the work. -

Brahms Reimagined by René Spencer Saller

CONCERT PROGRAM Friday, October 28, 2016 at 10:30AM Saturday, October 29, 2016 at 8:00PM Jun Märkl, conductor Jeremy Denk, piano LISZT Prometheus (1850) (1811–1886) MOZART Piano Concerto No. 23 in A major, K. 488 (1786) (1756–1791) Allegro Adagio Allegro assai Jeremy Denk, piano INTERMISSION BRAHMS/orch. Schoenberg Piano Quartet in G minor, op. 25 (1861/1937) (1833–1897)/(1874–1951) Allegro Intermezzo: Allegro, ma non troppo Andante con moto Rondo alla zingarese: Presto 23 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS These concerts are part of the Wells Fargo Advisors Orchestral Series. Jun Märkl is the Ann and Lee Liberman Guest Artist. Jeremy Denk is the Ann and Paul Lux Guest Artist. The concert of Saturday, October 29, is underwritten in part by a generous gift from Lawrence and Cheryl Katzenstein. Pre-Concert Conversations are sponsored by Washington University Physicians. Large print program notes are available through the generosity of The Delmar Gardens Family, and are located at the Customer Service table in the foyer. 24 CONCERT CALENDAR For tickets call 314-534-1700, visit stlsymphony.org, or use the free STL Symphony mobile app available for iOS and Android. TCHAIKOVSKY 5: Fri, Nov 4, 8:00pm | Sat, Nov 5, 8:00pm Han-Na Chang, conductor; Jan Mráček, violin GLINKA Ruslan und Lyudmila Overture PROKOFIEV Violin Concerto No. 1 I M E TCHAIKOVSKY Symphony No. 5 AND OCK R HEILA S Han-Na Chang SLATKIN CONDUCTS PORGY & BESS: Fri, Nov 11, 10:30am | Sat, Nov 12, 8:00pm Sun, Nov 13, 3:00pm Leonard Slatkin, conductor; Olga Kern, piano SLATKIN Kinah BARBER Piano Concerto H S ODI C COPLAND Billy the Kid Suite YBELLE GERSHWIN/arr. -

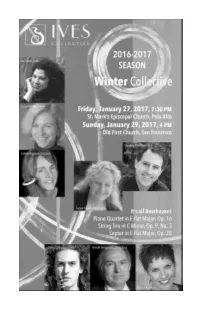

Ives 2017 Winter Program Book

IVES COLLECTIVE Season 2 Spring Collective Roy Malan, violin; Roberta Freier, violin Susan Freier, viola; Stephen Harrison, cello Elizabeth Schumann, piano Susanne Mentzer, mezzo soprano Friday,Please May 5,save 2017, these7:30 PM dates! St. Mark’s Episcopal Church, Palo Alto Sunday, May 7, 2016, 4PM Old First Church, San Francisco Ottorino Respighi: Il Tramonto Johannes Brahms: Songs for Voice, Viola and Piano, Op. 91 Johannes Brahms: Piano Quartet in C minor, Op. 60 Salon Concert Our Salon series, moderated by musicologist, Dr. Derek Katz, takes place in the intimacy and comfort of a beautiful Palo Alto homes. We invite you to experience music in a setting that eliminates the boundaries between artist and listener. Together with our “house guests” we share ideas about musical interpretation and inspiration over champagne and appetizers. Spring Salon April 30, 2017, 4 PM Johannes Brahms: Piano Quartet in C Minor, Op. 60 These intimate spaces seat a maximum of 50 guests. Street parking is available. 2 Winter Collective IVES COLLECTIVE Kay Stern, violin; Susan Freier, viola Stephen Harrison, cello; Susan Vollmer, horn Julie Green Gregorian, bassoon; Carlos Ortega, clarinet Arnold Gregorian, string bass; Lori Lack, piano It’s all Beethoven! (1770-1827) Piano Quartet in E-flat Major, Op. 16 (1796) Grave – Allegro, ma non troppo Andante cantabile Rondo: Allegro, ma non troppo String Trio in C minor, Op. 9, No.3 (1798) Allegro con spirito Adagio con espressione Scherzo: Allegro molto e vivace Finale: Presto Intermission Septet in E-flat Major, Op. 20 (1799) Adagio - Allegro con brio Adagio cantabile Tempo di Menuetto Andante con Variazioni Scherzo: Allegro molto e vivace Andante con molto Marcia - Presto 3 The Young Beethoven in Vienna and Chamber Music Beethoven left his childhood home of Bonn for Vienna, where he would remain for the rest of his life, in 1792. -

WALTON, William Turner Piano Quartet / Violin Sonata / Toccata (M

WALTON, William Turner Piano Quartet / Violin Sonata / Toccata (M. Jones, S.-J. Bradley, T. Lowe, A. Thwaite) Notes to performers by Matthew Jones Walton, Menuhin and ‘shifting’ performance practice The use of vibrato and audible shifts in Walton’s works, particularly the Violin Sonata, became (somewhat unexpectedly) a fascinating area of enquiry and experimentation in the process of preparing for the recording. It is useful at this stage to give some historical context to vibrato. As late as in Joseph Joachim’s treatise of 1905, the renowned violinist was clear that vibrato should be used sparingly,1 through it seems that it was in the same decade that the beginnings of ‘continuous vibrato use’ were appearing. In the 1910s Eugene Ysaÿe and Fritz Kreisler are widely credited with establishing it. Robin Stowell has suggested that this ‘new’ vibrato began to evolve partly because of the introduction of chin rests to violin set-up in the early nineteenth century.2 I suspect the evolution of the shoulder rest also played a significant role, much later, since the freedom in the left shoulder joint that is more accessible (depending on the player’s neck shape) when using a combination of chin and shoulder rest facilitates a fluid vibrato. Others point to the adoption of metal strings over gut strings as an influence. Others still suggest that violinists were beginning to copy vocal vibrato, though David Milsom has observed that the both sets of musicians developed the ‘new vibrato’ roughly simultaneously.3 Mark Katz persuasively posits the idea that much of this evolution was due to the beginning of the recording process. -

Female Composer Segment Catalogue

FEMALE CLASSICAL COMPOSERS from past to present ʻFreed from the shackles and tatters of the old tradition and prejudice, American and European women in music are now universally hailed as important factors in the concert and teaching fields and as … fast developing assets in the creative spheres of the profession.’ This affirmation was made in 1935 by Frédérique Petrides, the Belgian-born female violinist, conductor, teacher and publisher who was a pioneering advocate for women in music. Some 80 years on, it’s gratifying to note how her words have been rewarded with substance in this catalogue of music by women composers. Petrides was able to look back on the foundations laid by those who were well-connected by family name, such as Clara Schumann and Fanny Mendelssohn-Hensel, and survey the crop of composers active in her own time, including Louise Talma and Amy Beach in America, Rebecca Clarke and Liza Lehmann in England, Nadia Boulanger in France and Lou Koster in Luxembourg. She could hardly have foreseen, however, the creative explosion in the latter half of the 20th century generated by a whole new raft of female composers – a happy development that continues today. We hope you will enjoy exploring this catalogue that has not only historical depth but a truly international voice, as exemplified in the works of the significant number of 21st-century composers: be it the highly colourful and accessible American chamber music of Jennifer Higdon, the Asian hues of Vivian Fung’s imaginative scores, the ancient-and-modern syntheses of Sofia Gubaidulina, or the hallmark symphonic sounds of the Russian-born Alla Pavlova. -

Robert Schumann (1810-1856) Piano Quartet in E Op 47 (1842

Robert Schumann (1810-1856) Piano Quartet in E♭ Op 47 (1842) Sostenuto assai — Allegro ma non troppo Scherzo. Molto vivace Andante cantabile Finale. Vivace Coming after his 'Liederjahre' of 1840 and the subsequent 'Symphonic Year' of 1841, 1842 was Schumann's 'Chamber Music Year': three string quartets, the particularly successful piano quintet and today's piano quartet. Such creativity may have been initiated by Schumann at last winning, in July 1840, the protracted legal case in which his ex-teacher Friedrich Wieck, attempted to forbid him from marrying Wieck's daughter, the piano virtuoso Clara. They were married on 12 September 1840, the day before Clara's 21st birthday. 1842, however, did not start well for the Schumanns. Robert accompanied Clara at the start of her concert tour of North Germany, but he tired of being in her shadow, returned home to Leipzig in a state of deep melancholy, and comforted himself with beer, champagne and, unable to compose, contrapuntal exercises. Clara's father spread an unfounded and malicious rumour that the Schumanns had separated. However, in April Clara returned and Robert started a two-month study of the string quartets of Haydn, Mozart and Beethoven. During June he wrote the first two of his own three quartets, the third following in July. He dedicated them to his Leipzig friend and colleague Felix Mendelssohn. The three quartets were first performed on September 13, for Clara's birthday. She thought them 'new and, at the same time, lucid, finely worked and always in quartet idiom' - a comment reflecting Schumann the critic's own view that the ‘proper’ quartet style should avoid ‘symphonic furore’ and aim rather for a conversational tone in which ‘everyone has something to say’. -

Spohr and Schumann

SPOHR AND SCHUMANN by Keith Warsop OR MOST PEOPLE the link between Louis Spohr and Robert Schumann is limited to the latter's negative criticism of the Historrcai Symphony. In fact, the two musicians had a high regard for each other's compositions even though they each sometimes had reservations about particular aspects of certain individual works. Unfortunately, Spohr broke off his memoirs when he reached June 1838 shortly before he and Schumann met for the first time so we do not have his considered thoughts about Schumann's music in general. However, in the section of the memoirs added by his second wife, Marianne, after Spohr's death, she records that after the stay in Carlsbad detailed by Spohr in the last paragraphs he wrote down himself, they stopped in Leipzig on their way home. There, Marianne continues, "it was a source of great pleasure to him to make the long-desired acquaintance of Robert Schumann who, though in other respects exceedingly quiet and reserved, yet evinced his admiration of Spohr with great warmth and gratified him by the performanee of several of his interesting fantasias. " The two composers had, however, been in touch a few months before through the agency of a third composer, Felix Mendelssohn. On 24th November 1836, Mendelssohn wrote to Spohr requesting a song for inclusion in the wedding album of his new bride, Cdcilie Jeanrenaud, and on l3th December wrote again to thank Spohr for the song 'Was mir wohl tibrig bliebe', WoO96 (later included by Spohr as No.5 of his Op.139 Lieder collection). -

Download Program Notes

Notes on the Program By James M. Keller, Program Annotator, The Leni and Peter May Chair Piano Quintet in F minor, Op. 34 Johannes Brahms ohannes Brahms was 29 years old in 1862, seated at the other piano. Ironically, critics Jwhen he embarked on this seminal mas- now complained that the work lacked the terpiece of the chamber-music repertoire, sort of warmth that string instruments would though the work would not reach its final have provided — the opposite of Joachim’s form as his Piano Quintet until two years objection. Unlike the original string-quintet later. He was no beginner in chamber music version, which Brahms burned, the piano when he began this project. He had already duet was published — and is still performed written dozens of ensemble works before and appreciated — as his Op. 34bis. he dared to publish one, his B-major Piano By this time, however, Brahms must have Trio (Op. 8) of 1853–54. Among those early, grown convinced of the musical merits of his unpublished chamber pieces were 20-odd material and, with some coaxing from his string quartets, all of which he consigned friend Clara Schumann, he gave the piece to destruction prior to finally publishing his one more try, incorporating the most idiom- three mature works in that classic genre in atic aspects of both versions. The resulting the 1870s. In truth, he did get some use out Piano Quintet, the composer’s only essay of those early quartets — to paper the walls in that genre (and no wonder, after all that and ceilings of his apartment. -

Nicolas Namoradze Honens Prize Laureate Chamber Music / Works for Piano & Voice

NICOLAS NAMORADZE HONENS PRIZE LAUREATE CHAMBER MUSIC / WORKS FOR PIANO & VOICE K. Agócs Immutable Dreams (quintet) Bartók Piano Quintet Beethoven Sonata for Piano and Violin in A Major Op. 12 No. 2 Quintet for Piano and Winds Op. 16 Sonata for Piano and Horn in F Major Op. 17 Sonata for Piano and Violin in F Major Op. 24 Sonata for Piano and Cello in A Major Op. 69 Sonata for Piano and Cello in D Major Op. 102 No. 2 Brahms Piano Trio in B Major Op. 8 Piano Quartet in G minor Op. 25 selections from Waltzes Op. 39 Sonata for Piano and Violin in G Major Op. 78 Sonata for Piano and Cello in F Major Op. 99 Piano Trio in C minor Op. 101 Britten Gemini Variations for flute, violin and piano four-hands (Secondo) Cartan Introduction et Allegro for Piano and Wind Quintet Castiglioni Quickly—Variations for Chamber Ensemble Copland Appalachian Spring (chamber version for 13 players) Why do the shut me out of heaven? (voice and piano) Danzon Cubano (Piano I) Rodeo Hoe-Down (Piano I) Debussy Sonata for Piano and Violin L. 140 La Mer (transcription for piano four-hands / Secondo) Jeux (transcription for two pianos: Roques / Primo) Petite Suite (Secondo) Prélude à l’après-midi d’une faune (transcription for two pianos / Piano I) Prélude à l’après-midi d’une faune (transcription for piano four-hands: Ravel / Secondo) Danses sacrée et profane (transcription for two pianos / Piano II) Dvorak selections from Slavonic Dances Opp. 46 & 72 Dohnányi selections from Ruralia Hungarica Op. -

A Study of Ludwig Van Beethoven's Piano Sonata Op. 111

Southern Illinois University Carbondale OpenSIUC Research Papers Graduate School Fall 11-4-2011 A STUDY OF LUDWIG VAN BEETHOVEN’S PIANO SONATA OP. 111, ROBERT SCHUMANN’S OP.6 AND MAURICE RAVEL’S JEUX D’EAU Ji Hyun Kim [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://opensiuc.lib.siu.edu/gs_rp Recommended Citation Kim, Ji Hyun, "A STUDY OF LUDWIG VAN BEETHOVEN’S PIANO SONATA OP. 111, ROBERT SCHUMANN’S OP.6 AND MAURICE RAVEL’S JEUX D’EAU" (2011). Research Papers. Paper 174. http://opensiuc.lib.siu.edu/gs_rp/174 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at OpenSIUC. It has been accepted for inclusion in Research Papers by an authorized administrator of OpenSIUC. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A STUDY OF LUDWIG VAN BEETHOVEN’S PIANO SONATA OP. 111, ROBERT SCHUMANN’S OP.6 AND MAURICE RAVEL’S JEUX D’EAU by JI HYUN KIM B.M., CHUNG- ANG University, 2006 A Research Paper Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Master of Music Degree School of Music in the Graduate School Southern Illinois University Carbondale November 2011 RESEARCH PAPER APPROVAL A STUDY OF LUDWIG VAN BEETHOVEN’S PIANO SONATA OP. 111, ROBERT SCHUMANN’S OP.6 AND MAURICE RAVEL’S JEUX D’EAU By JI HYUN KIM A Research Paper Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Music in the field of Piano Performance Approved by: Dr. Junghwa Lee, Chair Dr. Eric Mandat Dr.