Manufacturing Europe

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Public and Private Broadcast Media in Turkey: Developments and Controversies

Public and Private Broadcast Media in Turkey: Developments and Controversies Radio and television in Turkey constitute the focal point of technologic, legal, cultural, economic and political discussion. They are also considered as a power and supervision tool by those ones in the country who manage societies, political and commercial power groups and media researchers.1 Especially, TV has been viewed as the most effective tool of media in the Turkish land2. Such functions of broadcast media can serve as a channel for projecting the political views of the public.3 Over the past few years, the Turkish broadcast media has been at an extremely important position with respect to its influence on the society. Recently, an important increase is in question in the number of private radio and television organizations, where public broadcast has a long history in the nation. The swift increase in private radio-television organizations, live nested with political aims and economical purposes. Particularly, when effect of economic liberalization and globalization were experienced, the overt and covert influence of private radio-television broadcasting over democratization has been questioned by the whole society. It is simply because the present structures and objectives of private radio-television organizations are based on facilitating the works of media owners and use of their power over society. History of Turkish Broadcast Media The effect of broadcast media on the public intensifies as a result of developments in communication media and technologies, and whether these developments support democratic practices, whether the government puts pressure on broadcast media and whether broadcast media is a force for the good of the public are subjects wildly debated in Turkey. -

In Afghanistan Afsar Sadiq Shinwari* School of Journalism and Communication, Hebei University, Baoding, Hebei, China

un omm ica C tio Shinwari, J Mass Communicat Journalism 2019, 9:1 s n s a & M J o f u o Journal of r l n a a n l r i s u m o J ISSN: 2165-7912 Mass Communication & Journalism Review Article OpenOpen Access Access Media after Interim Administration (December/2001) in Afghanistan Afsar Sadiq Shinwari* School of Journalism and Communication, Hebei University, Baoding, Hebei, China Abstract The unbelievable growth of media since 2001 is one of the greatest achievements of Afghan government. Now there are almost 800 publications, 100TV and 302 FM radio stations, 6 telecommunication companies, tens of news agencies, more than 44 licensed ISPs internet provider companies and several number of production groups are busy to broadcast information, drama serial, films according to the afghan Culture, and also connected the people with each other on national and international level. Afghanistan is a nation of 30 million people, and a majority live in its 37,000 villages. But low literacy rate (38.2%) is the main obstacle in Afghanistan, most of the people who lived in rural area are not educated and they are only have focus on radio and TV broadcasting. So, the main purpose of this study is the rapid growth of media in Afghanistan after the Taliban regime, but most of those have uncertain future. Keywords: Traditional media; New media; Social media; Media law programs and also a huge number of publications, mobile Networks, press clubs, newspaper, magazines, news agencies and internet Introduction were appeared at the field of information and technology. -

Wrth2016intradiosuppl2 A16

This file is a supplement to the 2016 edition of World Radio TV Handbook, and summarises the changes to the schedules printed in the book resulting from the implementation of the 2016 “A” season schedules. Contact details and other information about the stations shown in this file can be found in the International Radio section of WRTH 2016. If you haven’t yet got your copy, the book can be ordered from Amazon, your nearest bookstore or directly from our website at www.wrth.com/_shop WRTH INTERNATIONAL RADIO SCHEDULES - MAY 2016 Notes for the International Radio section Country abbreviation codes are shown after the country name. The three-letter codes after each frequency are transmitter site codes. These, and the Area/Country codes in the Area column, can be decoded by referring to the tables in the at the end of the file. Where a frequency has an asterisk ( *) etc. after it, see the ‘ KEY ’ section at the end of the sched - ule entry. The following symbols are used throughout this section: † = Irregular transmissions/broadcasts; ‡ = Inactive at editorial deadline; ± = variable frequency; + = DRM (Digital Radio Mondiale) transmission. ALASKA (ALS) ANGOLA (AGL) KNLS INTERNATIONAL (Rlg) ANGOLAN NATIONAL RADIO (Pub) kHz: 7355, 9655, 9920, 11765, 11870 kHz: 945 Summer Schedule 2016 Summer Schedule 2016 Chinese Days Area kHz English Days Area kHz 0800-1200 daily EAs 9655nls 2200-2300 daily SAf 945mul 1300-1400 daily EAs 9655nls, 9920nls French Days Area kHz 1400-1500 daily EAs 7355nls 2100-2200 daily SAf 945mul English Days Area kHz Lingala -

Twenty-Five Years of Consumer Bankruptcy in Continental Europe: Internalizing Negative Externalities and Humanizing Justice in Denmark Y Jasonj

Twenty-five Years of Consumer Bankruptcy in Continental Europe: Internalizing Negative Externalities and Humanizing Justice in Denmark y JasonJ. Kilborn*, John Marshall Law School, Chicago, USA Abstract This paper explores the problems and processes that led to the birth of consumer bankruptcy in continental Europe, a process that began in Denmark in January1972 andculminatedwiththe adoption of the Danish consumer debt adjust- ment act, G×ldssaneringslov, on 9 May 1984. While this law is often described in primarily humanitarian terms, in the sense of o¡ering a respite to ‘‘hopelessly indebted’’ individuals, both the motivation for the law and its intended scope were not simply accretions on an already multi-layered welfare system. Instead, the law was designedprimarilyasapragmatic responseto economically wastefulcollections activities that imposed negative externalities on debtors, creditors, and especially Danish societyand state co¡ers; the law was intendedto forcecreditorsto internalize (or eliminate) these externalities with respect to all debtors unable to pay their debts within a reasonable period of 5 years. The paper also examines the growing pains of this new system. The law originally left signi¢cant administrative discretion to judges, which produced vast disparities in treatment of cases in di¡erent regions of the country. Ultimately, a reform implemented in October 2005 made the system more accessible, more unitary throughout the country, and more humane. The e¡ects of this reform are already visible in statistical observations of the system, though signi¢cant regional variations persist. Giventhe striking coincidence in tim- ing, this paper also o¡ers brief comparative comments on the parallel designöbut verydi¡erente¡ectöof the most signi¢cant reformofthe USconsumerbankruptcy law, also e¡ective in October 2005. -

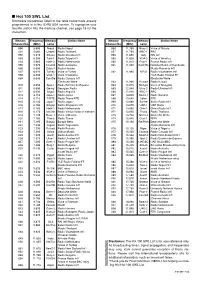

Hot 100 SWL List Shortwave Frequencies Listed in the Table Below Have Already Programmed in to the IC-R5 USA Version

I Hot 100 SWL List Shortwave frequencies listed in the table below have already programmed in to the IC-R5 USA version. To reprogram your favorite station into the memory channel, see page 16 for the instruction. Memory Frequency Memory Station Name Memory Frequency Memory Station Name Channel No. (MHz) name Channel No. (MHz) name 000 5.005 Nepal Radio Nepal 056 11.750 Russ-2 Voice of Russia 001 5.060 Uzbeki Radio Tashkent 057 11.765 BBC-1 BBC 002 5.915 Slovak Radio Slovakia Int’l 058 11.800 Italy RAI Int’l 003 5.950 Taiw-1 Radio Taipei Int’l 059 11.825 VOA-3 Voice of America 004 5.965 Neth-3 Radio Netherlands 060 11.910 Fran-1 France Radio Int’l 005 5.975 Columb Radio Autentica 061 11.940 Cam/Ro National Radio of Cambodia 006 6.000 Cuba-1 Radio Havana /Radio Romania Int’l 007 6.020 Turkey Voice of Turkey 062 11.985 B/F/G Radio Vlaanderen Int’l 008 6.035 VOA-1 Voice of America /YLE Radio Finland FF 009 6.040 Can/Ge Radio Canada Int’l /Deutsche Welle /Deutsche Welle 063 11.990 Kuwait Radio Kuwait 010 6.055 Spai-1 Radio Exterior de Espana 064 12.015 Mongol Voice of Mongolia 011 6.080 Georgi Georgian Radio 065 12.040 Ukra-2 Radio Ukraine Int’l 012 6.090 Anguil Radio Anguilla 066 12.095 BBC-2 BBC 013 6.110 Japa-1 Radio Japan 067 13.625 Swed-1 Radio Sweden 014 6.115 Ti/RTE Radio Tirana/RTE 068 13.640 Irelan RTE 015 6.145 Japa-2 Radio Japan 069 13.660 Switze Swiss Radio Int’l 016 6.150 Singap Radio Singapore Int’l 070 13.675 UAE-1 UAE Radio 017 6.165 Neth-1 Radio Netherlands 071 13.680 Chin-1 China Radio Int’l 018 6.175 Ma/Vie Radio Vilnius/Voice -

Dx Magazine 12/2003

12 - 2003 All times mentioned in this DX MAGAZINE are UTC - Alle Zeiten in diesem DX MAGAZINE sind UTC Staff of WORLDWIDE DX CLUB: PRESIDENT AND CHIEF EDITOR ..C WWDXC Headquarters, Michael Bethge, Postfach 12 14, D-61282 Bad Homburg, Germany B daytime +49-6102-2861, evening/weekend +49-6172-390918 F +49-6102-800999 E-Mail: [email protected] V Internet: http://www.wwdxc.de BROADCASTING NEWS EDITOR . C Dr. Jürgen Kubiak, Goltzstrasse 19, D-10781 Berlin, Germany E-Mail: [email protected] LOGBOOK EDITOR .............C Ashok Kumar Bose, Apt. #421, 3420 Morning Star Drive, Mississauga, ON, L4T 1X9, Canada V E-Mail: [email protected] QSL CORNER EDITOR ..........C Richard Lemke, 60 Butterfield Crescent, St. Albert, Alberta, T8N 2W7, Canada V E-Mail: [email protected] TOP NEWS EDITOR (Internet) ....C Wolfgang Büschel, Hoffeld, Sprollstrasse 87, D-70597 Stuttgart, Germany V E-Mail: [email protected] TREASURER & SECRETARY .....C Karin Bethge, Urseler Strasse 18, D-61348 Bad Homburg, Germany NEWCOMER SERVICE OF AGDX . C Hobby-Beratung, c/o AGDX, Postfach 12 14, D-61282 Bad Homburg, Germany (please enclose return postage) Each of the editors mentioned above is self-responsible for the contents of his composed column. Furthermore, we cannot be responsible for the contents of advertisements published in DX MAGAZINE. We have no fixed deadlines. Contributions may be sent either to WWDXC Headquarters or directly to our editors at any time. If you send your contributions to WWDXC Headquarters, please do not forget to write all contributions for the different sections on separate sheets of paper, so that we are able to distribute them to the competent section editors. -

Download Pdf Here

THE POPULAR PRESS HOLDINGS IN THE MIDDLE EAST DEPARTMENT JOSEPH REGENSTEIN LIBRARY UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO Introduction: Survey of the Popular Press in the Islamic World 1 I. Arabic 25 II. Armenian, Azeri, Georgian, Kurdish and Russian 44 III. English, French and Hebrew 46 IV. Persian 54 V. Ottoman / Turkish 107 Appendices: 163 Persian Newspapers published in India, Middle Eastern Newspapers at CRL, Middle Eastern Newspapers Currently Received by the Library Official Gazettes in the Middle East Department Select bibliographies are included at the end of each section. Though compilation of this list was stopped in the mid1990s, we believe it remains useful to library patrons as it contains information about materials that are not in the library catalog and thus can be found no other way. In the years since, new materials have been acquired, some uncataloged materials have been cataloged, and some items have been moved. It is important to communicate with the Middle East Department to determine how to access materials—especially those listed as uncataloged. For further information, please consult a staff member in the Middle East Department office, JRL 560 (open Monday through Friday, 9AM to 5PM), or contact Marlis Saleh (details at http://guides.lib.uchicago.edu/mideast). Middle Eastern Popular Press 1 1. INTRODUCTION: SURVEY OF THE POPULAR PRESS IN THE ISLAMIC WORLD. Background: The introduction of a popular newspaper and serial press to the Islamic world came with the introduction of the western newspaper form itself, in part a product of 18th century European, particularly French, influence on the Ottoman government in Istanbul, and Napoleon's invasion of Egypt in 17981801. -

Talaat Pasha's Report on the Armenian Genocide.Fm

Gomidas Institute Studies Series TALAAT PASHA’S REPORT ON THE ARMENIAN GENOCIDE by Ara Sarafian Gomidas Institute London This work originally appeared as Talaat Pasha’s Report on the Armenian Genocide, 1917. It has been revised with some changes, including a new title. Published by Taderon Press by arrangement with the Gomidas Institute. © 2011 Ara Sarafian. All Rights Reserved. ISBN 978-1-903656-66-2 Gomidas Institute 42 Blythe Rd. London W14 0HA United Kingdom Email: [email protected] CONTENTS Introduction by Ara Sarafian 5 Map 18 TALAAT PASHA’S 1917 REPORT Opening Summary Page: Data and Calculations 20 WESTERN PROVINCES (MAP) 22 Constantinople 23 Edirne vilayet 24 Chatalja mutasarriflik 25 Izmit mutasarriflik 26 Hudavendigar (Bursa) vilayet 27 Karesi mutasarriflik 28 Kala-i Sultaniye (Chanakkale) mutasarriflik 29 Eskishehir vilayet 30 Aydin vilayet 31 Kutahya mutasarriflik 32 Afyon Karahisar mutasarriflik 33 Konia vilayet 34 Menteshe mutasarriflik 35 Teke (Antalya) mutasarriflik 36 CENTRAL PROVINCES (MAP) 37 Ankara (Angora) vilayet 38 Bolu mutasarriflik 39 Kastamonu vilayet 40 Janik (Samsun) mutasarriflik 41 Nigde mutasarriflik 42 Kayseri mutasarriflik 43 Adana vilayet 44 Ichil mutasarriflik 45 EASTERN PROVINCES (MAP) 46 Sivas vilayet 47 Erzerum vilayet 48 Bitlis vilayet 49 4 Talaat Pasha’s Report on the Armenian Genocide Van vilayet 50 Trebizond vilayet 51 Mamuretulaziz (Elazig) vilayet 52 SOUTH EASTERN PROVINCES AND RESETTLEMENT ZONE (MAP) 53 Marash mutasarriflik 54 Aleppo (Halep) vilayet 55 Urfa mutasarriflik 56 Diyarbekir vilayet -

Mardin Sancağinda Mülki Ve Askeri Memurlarin Görev

Uluslararası Sosyal Araştırmalar Dergisi / The Journal of International Social Research Cilt: 13 Sayı: 71 Haziran 2020 & Volume: 13 Issue: 71 June 2020 www.sosyalarastirmalar.com Issn: 1307 - 9581 MARDİN SANCAĞINDA MÜLKİ VE ASKERİ MEMURLARIN GÖREV SUİSTİMALLERİ ÜZERİNE BİR DEĞERLENDİRME (1900 - 1920) AN EVALUATION ON THE WRONGDOINGS OF CIVIL AND MILITARY OFFICERS IN MARDIN SANJAK (1900 - 1920) Bilal ALTAN Ö z et Mardin idari statüsü olarak 19. yüzyılın ikinci yarısından Cumhuriyete kadar uzanan süreçte Diyarbekir Vilayetine bağlı bir sancaktır. Osmanlı İmparatorluğu’nda Tanzimat Devrinde merkeziyetçiliği modern anlamda artıracak düzenlemeler mülki ve askeri alana da yansımıştır. İdari teşkilattaki değişim yeni memurlukların ortaya çıkmasında etki li olmuştur. Çıkartılan kanunlarla memurların görev ve sorumlulukları ayrı ayrı belirlenmiştir. Tüm İ mparatorlukta tayin edilen memurlardan görevini hakkıyla ifa edenler olduğu gibi görev suiistimaline giden memurlar da oldukça fazlaydı. Bu çalışmada 20. y üzyılın başlarında Mardin sancak merkezi ile sancağa bağlı Cizre, Midyat, Nusaybin ve Savur kazalarında görev ifa eden mülki ve askeri memurların kanunlara aykırı mahiyette yolsuzluk, usulsüzlük, rüşvet gibi memuriyetle bağdaşmayacak davranışlar sergilemel erine dair muhtelif görev suistimalleri değerlendirmek amaçlanmıştır. Anahtar Kelimeler: Mardin Sancağı, Mülki, Askeri, Memur, Tahkikat . Abstract Mardin had the administrative status of a sanjak affiliated to Diyarbekir Province from the second half of the 19th century until the establishment of the republic. The arrangements that increased centralization in the modern sense in the Tanzimat Era in the Ottoman Empire were also reflected in the civil and military fields. The change in the administrative organization was also effective in the emergence of new civil services. The duties and responsibilities of civil servants are determined separately with the laws introduced. -

FIGURE 8.1 I EUROPE Stretching from Iceland in the Atlantic to The

FIGURE 8.1 I EUROPE Stretching from Iceland in the Atlantic to the Black Sea, Europe includes 40 countries, ranging in size from large states, such as France and Germany, to the microstates of Liechtenstein, Andorra, San Marino, and Monaco. Currently the population of the region is about 531 mil- lion. Europe is highly urbanized and, for the most part, relatively wealthy, par- ticularly the western portion. However, economic and social differences between eastern and western Europe remain a problem. (left) Migration re- mains one of Europe’s most troublesome issues. While some immigrates will- ingly embrace European values and culture, others prefer to remain more distant by resisting cultural and political integration. In Britain, for example, there is ongoing debate about Muslim women wearing their traditional veils. (Dave Thompson/AP Wide World Photos) 8 Europe SETTING THE BOUNDARIES The European region is small compared to the United roots. The Greeks and Romans divided their worlds into problematic. Now some geography textbooks extend States. In fact, Europe from Iceland to the Black Sea the three continents of Europe, Asia, and Africa sepa- Europe to the border with Russia, which places the would fit easily into the eastern two-thirds of North rated by the Mediterranean Sea, the Red Sea, and the two countries of Ukraine and Belarus, former Soviet America. A more apt comparison would be Canada, Bosporus Strait. A northward extension of the Black Sea republics, in eastern Europe. Though an argument can as Europe, too, is a northern region. More than half was thought to separate Europe from Asia, and only in be made for that expanded definition of Europe, recent of Europe lies north of the 49th parallel, the line of the 16th century was this proven false. -

Choosing Between the Anglo-Saxon Model and a European-Style Alternative

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Research Papers in Economics CPB Discussion Paper No 40 October 2004 Is the American Model Miss World? Choosing between the Anglo-Saxon model and a European-style alternative Henri L.F. de Groot, Richard Nahuis and Paul J.G. Tang The responsibility for the contents of this CPB Discussion Paper remains with the author(s) CPB Netherlands Bureau for Economic Policy Analysis Van Stolkweg 14 P.O. Box 80510 2508 GM The Hague, the Netherlands Telephone +31 70 338 33 80 Telefax +31 70 338 33 50 Internet www.cpb.nl ISBN 90-5833-196-2 2 Abstract in English In Lisbon, the European Union has set itself the goal to become the most competitive economy in the world in 2010 without harming social cohesion and the environment. The motivation for introducing this target is the substantially higher GDP per capita of US citizens. The difference in income is mainly a difference in the number of hours worked per employee. In terms of productivity per hour and employment per inhabitant, several European countries score equally well or even better than the United States, while at the same time they outperform the United States with a more equal distribution of income. The European social models are at least as interesting as the US model that is often considered a role model. In an empirical analysis for OECD countries, we aim to unravel ‘the secret of success’. Our regression results show that income redistribution (through a social security system) does not necessarily lead to lower participation and higher unemployment, provided that countries supplement it with active labour market policies. -

Migration, Memory and Mythification: Relocation of Suleymani Tribes on the Northern Ottoman–Iranian Frontier

Middle Eastern Studies ISSN: 0026-3206 (Print) 1743-7881 (Online) Journal homepage: https://www.tandfonline.com/loi/fmes20 Migration, memory and mythification: relocation of Suleymani tribes on the northern Ottoman–Iranian frontier Erdal Çiftçi To cite this article: Erdal Çiftçi (2018) Migration, memory and mythification: relocation of Suleymani tribes on the northern Ottoman–Iranian frontier, Middle Eastern Studies, 54:2, 270-288, DOI: 10.1080/00263206.2017.1393623 To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/00263206.2017.1393623 Published online: 06 Nov 2017. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 361 View Crossmark data Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at https://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=fmes20 MIDDLE EASTERN STUDIES, 2018 VOL. 54, NO. 2, 270–288 https://doi.org/10.1080/00263206.2017.1393623 Migration, memory and mythification: relocation of Suleymani tribes on the northern Ottoman–Iranian frontier Erdal Cift¸ ci¸ a,b aHistory Department, Bilkent University, Ankara, Turkey; bHistory Department, Mardin Artuklu University, Mardin, Turkey Although some researchers have studied the relationship between hereditary Kurdish emirs and the Ottoman central government, there has been little discussion of the role played by Kurdish tribes, and Kurdish tribes in general have been omitted from scholars’ narratives. Researchers have mostly discussed how Idris-i Bidlisi became an intermediary between the Ottoman central government and the disinherited Kurdish emirs, some of whom had been removed from power by the Safavids. In this article, we will not focus on the condominium between the Ottoman central government and the Kurdish emirs, but rather, we will draw attention to the roles played by the Kurdish tribes – specifically, the role played by the Suleymani tribes during the period dominated by local political upheaval in the sixteenth century.