Why Here? Why Now? Why JAMS? Billy Tringali

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Oi Duck-Billed Platypus! This July! Text © Kes Gray, 2018

JULY 2019 EDITION Featuring buyer’s recommends and new titles in books, DVD & Blu-ray Cats sit on gnats, dogs sit on logs, and duck-billed platypuses sit on …? Find out in the hilarious Oi Duck-billed Platypus! this July! Text © Kes Gray, 2018. Illustrations © Jim Field, 2018. Gray, © Kes Text NEW for 2019 Oi Duck-billed Platypus! 9781444937336 PB | £6.99 Platypus Sales Brochure Cover v5.indd 1 19/03/2019 09:31 P. 11 Adult Titles P. 133 Children’s Titles P. 180 Entertainment Releases THIS PUBLICATION IS ALSO AVAILABLE DIGITALLY VIA OUR WEBSITE AT WWW.GARDNERS.COM “You need to read this book, Smarty’s a legend” Arthur Smith A Hitch in Time Andy Smart Andy Smart’s early adventures are a series of jaw-dropping ISBN: 978-0-7495-8189-3 feats and bizarre situations from RRP: £9.99 which, amazingly, he emerged Format: PB Pub date: 25 July 2019 unscathed. WELCOME JULY 2019 3 FRONT COVER Oi Duck-billed Platypus! by Kes Gray Age 1 to 5. A brilliantly funny, rhyming read-aloud picture book - jam-packed with animals and silliness, from the bestselling, multi-award-winning creators of ‘Oi Frog!’ Oi! Where are duck-billed platypuses meant to sit? And kookaburras and hippopotamuses and all the other animals with impossible-to-rhyme- with names... Over to you Frog! The laughter never ends with Oi Frog and Friends. Illustrated by Jim Field. 9781444937336 | Hachette Children’s | PB | £6.99 GARDNERS PUBLICATIONS ALSO INSIDE PAGE 4 Buyer’s Recommends PAGE 8 Recall List PAGE 11 Gardners Independent Booksellers Affiliate July Adult’s Key New Titles Programme publication includes a monthly selection of titles chosen specifically for PAGE 115 independent booksellers by our affiliate July Adult’s New Titles publishers. -

The Indigenous Shôjo: Transmedia Representations of Ainu Femininity In

Journal of Anime and Manga Studies Volume 1 The Indigenous Shôjo: Transmedia Representations of Ainu Femininity in Japan’s Samurai Spirits, 1993–2019 Christina Spiker Volume 1, Pages 138-168 Abstract: Little scholarly attention has been given to the visual representations of the Ainu people in popular culture, even though media images have a significant role in forging stereotypes of indigeneity. This article investigates the role of representation in creating an accessible version of indigenous culture repackaged for Japanese audiences. Before the recent mainstream success of manga/anime Golden Kamuy (2014–), two female heroines from the arcade fighting game Samurai Spirits (Samurai supirittsu)— Nakoruru and her sister Rimururu—formed a dominant expression of Ainu identity in visual culture beginning in the mid-1990s. Working through the in-game representation of Nakoruru in addition to her larger mediation in the anime media mix, this article explores the tensions embodied in her character. While Nakoruru is framed as indigenous, her body is simultaneously represented in the visual language of the Japanese shôjo, or “young girl.” This duality to her fetishized image cannot be reconciled and is critical to creating a version of indigenous femininity that Japanese audiences could easily consume. This paper historicizes various representations of indigenous Otherness against the backdrop of Japanese racism and indigenous activism in the late 1990s and early 2000s by analyzing Nakoruru’s official representation in the game franchise, including her appearance in a 2001 OVA, alongside fan interpretations of these characters in self-published comics (dôjinshi) criticized by Ainu scholar Chupuchisekor. Keywords: Ainu, indigenous studies, shôjo, gender, arcade gaming, stereotypes Author Bio: Christina M. -

Master List of Games This Is a List of Every Game on a Fully Loaded SKG Retro Box, and Which System(S) They Appear On

Master List of Games This is a list of every game on a fully loaded SKG Retro Box, and which system(s) they appear on. Keep in mind that the same game on different systems may be vastly different in graphics and game play. In rare cases, such as Aladdin for the Sega Genesis and Super Nintendo, it may be a completely different game. System Abbreviations: • GB = Game Boy • GBC = Game Boy Color • GBA = Game Boy Advance • GG = Sega Game Gear • N64 = Nintendo 64 • NES = Nintendo Entertainment System • SMS = Sega Master System • SNES = Super Nintendo • TG16 = TurboGrafx16 1. '88 Games ( Arcade) 2. 007: Everything or Nothing (GBA) 3. 007: NightFire (GBA) 4. 007: The World Is Not Enough (N64, GBC) 5. 10 Pin Bowling (GBC) 6. 10-Yard Fight (NES) 7. 102 Dalmatians - Puppies to the Rescue (GBC) 8. 1080° Snowboarding (N64) 9. 1941: Counter Attack ( Arcade, TG16) 10. 1942 (NES, Arcade, GBC) 11. 1943: Kai (TG16) 12. 1943: The Battle of Midway (NES, Arcade) 13. 1944: The Loop Master ( Arcade) 14. 1999: Hore, Mitakotoka! Seikimatsu (NES) 15. 19XX: The War Against Destiny ( Arcade) 16. 2 on 2 Open Ice Challenge ( Arcade) 17. 2010: The Graphic Action Game (Colecovision) 18. 2020 Super Baseball ( Arcade, SNES) 19. 21-Emon (TG16) 20. 3 Choume no Tama: Tama and Friends: 3 Choume Obake Panic!! (GB) 21. 3 Count Bout ( Arcade) 22. 3 Ninjas Kick Back (SNES, Genesis, Sega CD) 23. 3-D Tic-Tac-Toe (Atari 2600) 24. 3-D Ultra Pinball: Thrillride (GBC) 25. 3-D WorldRunner (NES) 26. 3D Asteroids (Atari 7800) 27. -

Graphic No Vels & Comics

GRAPHIC NOVELS & COMICS SPRING 2020 TITLE Description FRONT COVER X-Men, Vol. 1 The X-Men find themselves in a whole new world of possibility…and things have never been better! Mastermind Jonathan Hickman and superstar artist Leinil Francis Yu reveal the saga of Cyclops and his hand-picked squad of mutant powerhouses. Collects #1-6. 9781302919818 | $17.99 PB Marvel Fallen Angels, Vol. 1 Psylocke finds herself in the new world of Mutantkind, unsure of her place in it. But when a face from her past returns only to be killed, she seeks vengeance. Collects Fallen Angels (2019) #1-6. 9781302919900 | $17.99 PB Marvel Wolverine: The Daughter of Wolverine Wolverine stars in a story that stretches across the decades beginning in the 1940s. Who is the young woman he’s fated to meet over and over again? Collects material from Marvel Comics Presents (2019) #1-9. 9781302918361 | $15.99 PB Marvel 4 Graphic Novels & Comics X-Force, Vol. 1 X-Force is the CIA of the mutant world—half intelligence branch, half special ops. In a perfect world, there would be no need for an X-Force. We’re not there…yet. Collects #1-6. 9781302919887 | $17.99 PB Marvel New Mutants, Vol. 1 The classic New Mutants (Sunspot, Wolfsbane, Mirage, Karma, Magik, and Cypher) join a few new friends (Chamber, Mondo) to seek out their missing member and go on a mission alongside the Starjammers! Collects #1-6. 9781302919924 | $17.99 PB Marvel Excalibur, Vol. 1 It’s a new era for mutantkind as a new Captain Britain holds the amulet, fighting for her Kingdom of Avalon with her Excalibur at her side—Rogue, Gambit, Rictor, Jubilee…and Apocalypse. -

The 1970 Osaka Expo And/As Science Fiction

Swarthmore College Works Japanese Faculty Works Japanese 12-1-2011 The 1970 Osaka Expo And/As Science Fiction William O. Gardner Swarthmore College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://works.swarthmore.edu/fac-japanese Part of the Japanese Studies Commons Recommended Citation William O. Gardner. (2011). "The 1970 Osaka Expo And/As Science Fiction". Review Of Japanese Culture And Society. Volume 28, 26-43. https://works.swarthmore.edu/fac-japanese/16 This work is brought to you for free by Swarthmore College Libraries' Works. It has been accepted for inclusion in Japanese Faculty Works by an authorized administrator of Works. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The 1970 Osaka Expo and/ as Science Fiction William 0. Gardner B i{ I The Japan World Exposition of 1970, hosted by the city of Suita, Osaka and organized I around the idealistic theme of the "Progress and Harmony for Mankind," was the first world's fair held in an Asian country, and attracted a record 64 million visitors. Through its integration of advanced technology, immersive multi-media environments, and eye-popping architecture, Expo '70 projected Japan as a simulation-site for a future I I society. Indeed, many journalistic accounts heralded the expo as "mirai no toshi" (city of the future), just as the 1939-40 New York World's Fair had been cast as the "World of Tomorrow." At the same time, Expo '70 enacted an elaborate staging of Japan's relationship with the outside world, through massive "international" events such as the opening ceremony attended by the Showa emperor. -

Universidade De São Paulo Faculdade De

UNIVERSIDADE DE SÃO PAULO FACULDADE DE FILOSOFIA, LETRAS E CIÊNCIAS HUMANAS DEPARTAMENTO DE LETRAS ORIENTAIS PROGRAMA DE PÓS-GRADUAÇÃO EM LÍNGUA, LITERATURA E CULTURA JAPONESA PRISCILA GEROLDE GAVA A mitologia judaico-cristã e o herói japonês: a jornada mítica de Mudō Setsuna no mangá Angel Sanctuary Versão Corrigida São Paulo 2018 PRISCILA GEROLDE GAVA A mitologia judaico-cristã e o herói japonês: a jornada mítica de Mudō Setsuna no mangá Angel Sanctuary Versão Corrigida Dissertação de Mestrado apresentada ao Programa de Pós-Graduação em Língua, Literatura e Cultura Japonesa da Faculdade de Filosofia, Letras e Ciências Humanas da Universidade de São Paulo, como parte dos requisitos para obtenção do título de Mestre em Letras. Área de Concentração: Língua, Literatura e Cultura Japonesa Orientadora: Profª. Drª. Neide Hissae Nagae São Paulo 2018 Autorizo a reprodução e divulgação total ou parcial deste trabalho, por qualquer meio convencional ou eletrônico, para fins de estudo e pesquisa, desde que citada a fonte. O presente trabalho foi realizado com apoio da Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior - Brasil (CAPES) - Código de Financiamento 001. GAVA, P. G. A mitologia judaico-cristã e o herói japonês: a jornada mítica de Mudō Setsuna no mangá Angel Sanctuary. Dissertação (Mestrado em Língua, Literatura e Cultura Japonesa) – Faculdade de Filosofia, Letras e Ciências Humanas, Universidade de São Paulo, São Paulo, 2018. Aprovado em: Banca Examinadora Prof. Dr.____________________________Instituição:____________________________ Julgamento:_________________________ Assinatura:____________________________ Prof. Dr.____________________________Instituição:____________________________ Julgamento:_________________________ Assinatura:____________________________ Prof. Dr.____________________________Instituição:____________________________ Julgamento:_________________________ Assinatura:____________________________ AGRADECIMENTOS À Professora Doutora Neide Hissae Nagae pela orientação, apoio e paciência durante essa jornada no Mestrado. -

Protoculture Addicts #61

Sample file CONTENTS 3 ○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○ PROTOCULTURE ✾ PRESENTATION ........................................................................................................... 4 STAFF WHAT'S GOING ON? ANIME & MANGA NEWS .......................................................................................................... 5 Claude J. Pelletier [CJP] — Publisher / Manager VIDEO & MANGA RELEASES ................................................................................................... 6 Martin Ouellette [MO] — Editor-in-Chief PRODUCTS RELEASES .............................................................................................................. 8 Miyako Matsuda [MM] — Editor / Translator NEW RELEASES ..................................................................................................................... 10 MODEL NEWS ...................................................................................................................... 47 Contributors Aaron Dawe Kevin Lilliard, James S. Taylor REVIEWS Layout LIVE-ACTION ........................................................................................................................ 15 MODELS .............................................................................................................................. 46 The Safe House MANGA .............................................................................................................................. 54 Cover PA PICKS ............................................................................................................................ -

Sailor Mars Meet Maroku

sailor mars meet maroku By GIRNESS Submitted: August 11, 2005 Updated: August 11, 2005 sailor mars and maroku meet during a battle then fall in love they start to go futher and futher into their relationship boy will sango be mad when she comes back =:) hope you like it Provided by Fanart Central. http://www.fanart-central.net/stories/user/GIRNESS/18890/sailor-mars-meet-maroku Chapter 1 - sango leaves 2 Chapter 2 - sango leaves 15 1 - sango leaves Fanart Central A.whitelink { COLOR: #0000ff}A.whitelink:hover { BACKGROUND-COLOR: transparent}A.whitelink:visited { COLOR: #0000ff}A.BoxTitleLink { COLOR: #000; TEXT-DECORATION: underline}A.BoxTitleLink:hover { COLOR: #465584; TEXT-DECORATION: underline}A.BoxTitleLink:visited { COLOR: #000; TEXT-DECORATION: underline}A.normal { COLOR: blue}A.normal:hover { BACKGROUND-COLOR: transparent}A.normal:visited { COLOR: #000020}A { COLOR: #0000dd}A:hover { COLOR: #cc0000}A:visited { COLOR: #000020}A.onlineMemberLinkHelper { COLOR: #ff0000}A.onlineMemberLinkHelper:hover { COLOR: #ffaaaa}A.onlineMemberLinkHelper:visited { COLOR: #cc0000}.BoxTitleColor { COLOR: #000000} picture name Description Keywords All Anime/Manga (0)Books (258)Cartoons (428)Comics (555)Fantasy (474)Furries (0)Games (64)Misc (176)Movies (435)Original (0)Paintings (197)Real People (752)Tutorials (0)TV (169) Add Story Title: Description: Keywords: Category: Anime/Manga +.hack // Legend of Twilight's Bracelet +Aura +Balmung +Crossovers +Hotaru +Komiyan III +Mireille +Original .hack Characters +Reina +Reki +Shugo +.hack // Sign +Mimiru -

Newsletter 08/07 DIGITAL EDITION Nr

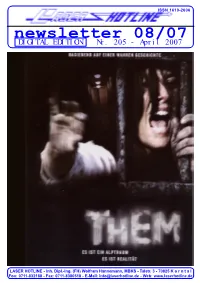

ISSN 1610-2606 ISSN 1610-2606 newsletter 08/07 DIGITAL EDITION Nr. 205 - April 2007 Michael J. Fox Christopher Lloyd LASER HOTLINE - Inh. Dipl.-Ing. (FH) Wolfram Hannemann, MBKS - Talstr. 3 - 70825 K o r n t a l Fon: 0711-832188 - Fax: 0711-8380518 - E-Mail: [email protected] - Web: www.laserhotline.de Newsletter 08/07 (Nr. 205) April 2007 editorial Gefühlvoll, aber nie kitschig: Susanne Biers Hallo Laserdisc- und DVD-Fans, da wieder ganz schön viel zusammen- Familiendrama über Lügen und Geheimnisse, liebe Filmfreunde! gekommen. An Nachschub für Ihr schmerzhafte Enthüllungen und tiefgreifenden Kaum ist Ostern vorbei, überraschen Entscheidungen ist ein Meisterwerk an Heimkino fehlt es also ganz bestimmt Inszenierung und Darstellung. wir Sie mit einer weiteren Ausgabe nicht. Unsere ganz persönlichen Favo- unseres Newsletters. Eigentlich woll- riten bei den deutschen Veröffentli- Schon lange hat sich der dänische Film von ten wir unseren Bradford-Bericht in chungen: THEM (offensichtlich jetzt Übervater Lars von Trier und „Dogma“ genau dieser Ausgabe präsentieren, emanzipiert, seine Nachfolger probieren andere doch im korrekten 1:2.35-Bildformat) Wege, ohne das Gelernte über Bord zu werfen. doch das Bilderbuchwetter zu Ostern und BUBBA HO-TEP. Zwei Titel, die Geblieben ist vor allem die Stärke des hat uns einen Strich durch die Rech- in keiner Sammlung fehlen sollten und Geschichtenerzählens, der Blick hinter die nung gemacht. Und wir haben es ge- bestimmt ein interessantes Double- Fassade, die Lust an der Brüchigkeit von nossen! Gerne haben wir die Tastatur Beziehungen. Denn nichts scheint den Dänen Feature für Ihren nächsten Heimkino- verdächtiger als Harmonie und Glück oder eine gegen Rucksack und Wanderschuhe abend abgeben würden. -

Read Book Angel Sanctuary: of Mushrooms and Boys

ANGEL SANCTUARY: OF MUSHROOMS AND BOYS PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Kaori Yuki | 200 pages | 06 Jul 2009 | Viz Media, Subs. of Shogakukan Inc | 9781421501260 | English | San Francisco, United States Angel Sanctuary: Of Mushrooms and Boys PDF Book An English-language translation was licensed in North America by Central Park Media , which published it on 10 July and re-released it on 24 May Archived from the original on 15 August Angel Sanctuary was critically and commercially well-received by English-language readers and critics, with Yuki's art and narrative highlighted as its strengths. After Rosiel absorbs Sandolphon to gain his power, an act which speeds up Rosiel's physical and mental decay, Sandolphon's remnants possess her, causing her to see Setsuna as a monster. Retrieved 23 October Buy Angel Sanctuary, Vol. Active Anime. Retrieved 14 May Description - Angel Sanctuary, Vol. Delta Vision. More information about this seller Contact this seller 3. I believe every angel has a different endgame in mind. Proceed to Basket. Realizing they cannot bear to be separated, Setsuna and Sara run away together and consummate their love, hoping to start a new life together. Godchild, Vol. Characters like to make sudden pronouncements of betrayals, and then monologue for pages and pages about what it meant. We are open! Original video animation. Manga:The Complete Guide. United Kingdom. Archived from the original on 16 February Archived from the original on 11 June Kaori Yuki. She now inhabits the body of Setsuna Mudo, a troubled teen in love with his sister Sara. Create a Want BookSleuth Can't remember the title or the author of a book? Captured and branded a fallen angel , Alexiel was punished by having her body frozen and her soul endlessly reincarnated as a human whose life is full of misery. -

Vol. 3 Issue 4 July 1998

Vol.Vol. 33 IssueIssue 44 July 1998 Adult Animation Late Nite With and Comics Space Ghost Anime Porn NYC: Underground Girl Comix Yellow Submarine Turns 30 Frank & Ollie on Pinocchio Reviews: Mulan, Bob & Margaret, Annecy, E3 TABLE OF CONTENTS JULY 1998 VOL.3 NO.4 4 Editor’s Notebook Is it all that upsetting? 5 Letters: [email protected] Dig This! SIGGRAPH is coming with a host of eye-opening films. Here’s a sneak peak. 6 ADULT ANIMATION Late Nite With Space Ghost 10 Who is behind this spandex-clad leader of late night? Heather Kenyon investigates with help from Car- toon Network’s Michael Lazzo, Senior Vice President, Programming and Production. The Beatles’Yellow Submarine Turns 30: John Coates and Norman Kauffman Look Back 15 On the 30th anniversary of The Beatles’ Yellow Submarine, Karl Cohen speaks with the two key TVC pro- duction figures behind the film. The Creators of The Beatles’Yellow Submarine.Where Are They Now? 21 Yellow Submarine was the start of a new era of animation. Robert R. Hieronimus, Ph.D. tells us where some of the creative staff went after they left Pepperland. The Mainstream Business of Adult Animation 25 Sean Maclennan Murch explains why animated shows targeted toward adults are becoming a more popular approach for some networks. The Anime “Porn” Market 1998 The misunderstood world of anime “porn” in the U.S. market is explored by anime expert Fred Patten. Animation Land:Adults Unwelcome 28 Cedric Littardi relates his experiences as he prepares to stand trial in France for his involvement with Ani- meLand, a magazine focused on animation for adults. -

Costellazione Manga: Explaining Astronomy Using Japanese Comics and Animation

Costellazione Manga: explaining astronomy using Japanese comics and animation Downloaded from: https://research.chalmers.se, 2021-09-30 20:30 UTC Citation for the original published paper (version of record): Dall` Olio, D., Ranalli, P. (2018) Costellazione Manga: explaining astronomy using Japanese comics and animation Communicating Astronomy with the Public Journal(24): 7-16 N.B. When citing this work, cite the original published paper. research.chalmers.se offers the possibility of retrieving research publications produced at Chalmers University of Technology. It covers all kind of research output: articles, dissertations, conference papers, reports etc. since 2004. research.chalmers.se is administrated and maintained by Chalmers Library (article starts on next page) Costellazione Manga: Explaining Astronomy Using Japanese Comics and Animation Resources Daria Dall’Olio Piero Ranalli Keywords Onsala Space Observatory, Chalmers Combient AB, Göteborg, Sweden; Public outreach, science communication, University of Technology, Sweden; Lund Observatory, Sweden informal education, planetarium show, ARAR, Planetarium of Ravenna and ASCIG, Italy [email protected] learning development [email protected] Comics and animation are intensely engaging and can be successfully used to communicate science to the public. They appear to stimulate many aspects of the learning process and can help with the development of links between ideas. Given these pedagogical premises, we conducted a project called Costellazione Manga, in which we considered astronomical concepts present in several manga and anime (Japanese comics and animations) and highlighted the physics behind them. These references to astronomy allowed us to introduce interesting topics of modern astrophysics and communicate astronomy-related concepts to a large spectrum of people.