The Indigenous Shôjo: Transmedia Representations of Ainu Femininity In

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Neo-Geo Hardware Specification

Confidential 0future is Neo-Geo Hardware Specification SNK Neo-Geo Hardware Specification Table of Contents Neo-Geo Specification ............................. Hardware .1 Special Features of the "3D-LINE SPRITE" ................ Hardware .3 Specification of Each Function ........................ Hardware .4 FIX .................................... Hardware .4 Background ................................ Hardware .4 3D-Line Sprite .............................. Hardware .4 Interrupts ...................................... Hardware .5 Interrupt-1 ................................ Hardware .5 Interrupt-2 ................................ Hardware .5 Access to Line Sprite Controller (LSPC) .................. Hardware .6 Address Map of the 68000 ........................... Hardware .8 Address Map of the 280 ............................ Hardware .10 I/O Map of the 280 ............................... Hardware .10 # Sound Function ................................. Hardware .10 Notes ....................................... Hardware .10 3D Line Sprite .................................. Hardware .12 Vertical and Horizontal Positions .................. Hardware .13 Example of the Number of Active Characters (ACT). Vertical Reduction (BIGV). and Horizontal Reduction (BIGH) Hardware .14 Address Mapping of the FIX Area (VRAM) (In the NTSC Mode)Hardware .15 Address Mapping of the FIX Area (VRAM) (In the PAL Mode) Hardware .16 Address Example of the 3D-Line Sprite .............. Hardware .17 Address Mapping of the 3D-Line Sprite .............. Hardware -

SAMURAI SHODOWN Patch Ver.2.12

SAMURAI SHODOWN Patch Ver.2.12 Changed / Improved Features ■Regarding found issues ・Resolved an issue where the sign indicating which side of the stage a disarmed weapon is located at would appear at unintended times. ・Resolved an issue where CHAM CHAM could not land attacks normally after performing a specific movement. ・Resolved an issue where CHAM CHAM would seemingly warp after performing a specific movement. ・Resolved an issue where opponents wearing Retro 3D skins would not glow red indicating they can be Guard Crushed. ■Regarding the Guard Crush mechanic Below offers an expanded view of the mechanics regarding the Guard Crush system: ・Opponents will be Guard Crushed once their internal Guard Crush meter reaches 0%. ・An opponent's internal Guard Crush meter decreases by a set amount depending on which attack they block. (An unarmed opponent's internal Guard Crush meter will not decrease when they block attacks.) ・Characters will glow red when they are able to be Guard Crushed. ・Opponents that are glowing red and block either Far or Near Standing Heavy Slashes will result in them being Guard Crushed on account of their internal Guard Crush meter reaching 0%. ・Attacks besides the ones listed above are able to reduce an opponent's internal Guard Crush Meter, but they can never bring it to 0% (and thus cannot be used to Guard Crush). ・Upon Guard Crushing an opponent, players have the ability to cancel out of the initial starting Heavy Slash (including any additional hits it may have),and into a Special Move, Weapon Flipping Technique, or Lightning Blade. -

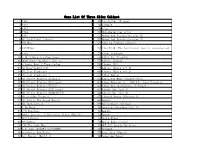

2475 in 1 Game List

Game List Of Three Sides Cabinet 1 1941 47 Air Gallet (Taiwan) 2 1942 48 Airwolf 3 1943 49 Ajax 4 1944 50 Akkanbeder(ver 2.5j) 5 1945 51 Akuma-Jou Dracula(version N) 6 10 Yard Fight (Japan) 52 Akuma-Jou Dracula(version P) 7 1943kai 53 Ales no Tsubasa (Japan) 8 1945Plus 54 Alex Kidd: The Lost Stars (set 2, unprotected) 9 19xx 55 Alien Syndrome 10 2 On 2 Open Ice Challenge 56 Alien vs. Predator 11 2020 Super Baseball (set 1) 57 Aliens (Japan) 12 3 Count Bout / Fire Suplex 58 Aliens (US) 13 3D_Beastorizer(US) 59 Aliens (World set 1) 14 3D_Star Gladiator 60 Aliens (World set 2) 15 3D_Star Gladiator 2 61 Alley Master 16 3D_Street Fighter EX(Asia) 62 Alligator Hunt (unprotected) 17 3D_Street Fighter EX(Japan) 63 Alpha Mission II / ASO II - Last Guardian 18 3D_Street Fighter EX(US) 64 Alpha One (prototype, 3 lives) 19 3D_Street Fighter EX2(Japan) 65 Alpine Ski (set 1) 20 3D_Street Fighter EX2PLUS(US) 66 Alpine Ski (set 2) 21 3D_Strider Hiryu 2 67 Altered Beast (Version 1) 22 3D_Tetris The Grand Master 68 Ambush 23 3D_Toshinden 2 69 Ameisenbaer (German) 24 4 En Raya 70 American Speedway (set 1) 25 4-D Warriors 71 Amidar 26 64th. Street - A Detective Story (World) 72 Amigo 27 800 Fathoms 73 Andro Dunos 28 88 Games! 74 Angel Kids (Japan) 29 '99 The Last War 75 APB-All Points Bulletin 30 A.B. Cop (FD1094 317-0169b) 76 Appoooh 31 Acrobatic Dog_Fight 77 Aqua Jack (World) 32 Act-Fancer (World 1) 78 Aquarium(Japan) 33 Act-Fancer (World 2) 79 Arabian Act-Fancer Cybernetick Hyper Weapon (Japan 34 80 Arabian (Atari) revision 1) 35 Action Fighter 81 Arabian -

The Otaku Phenomenon : Pop Culture, Fandom, and Religiosity in Contemporary Japan

University of Louisville ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository Electronic Theses and Dissertations 12-2017 The otaku phenomenon : pop culture, fandom, and religiosity in contemporary Japan. Kendra Nicole Sheehan University of Louisville Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.library.louisville.edu/etd Part of the Comparative Methodologies and Theories Commons, Japanese Studies Commons, and the Other Religion Commons Recommended Citation Sheehan, Kendra Nicole, "The otaku phenomenon : pop culture, fandom, and religiosity in contemporary Japan." (2017). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. Paper 2850. https://doi.org/10.18297/etd/2850 This Doctoral Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. This title appears here courtesy of the author, who has retained all other copyrights. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE OTAKU PHENOMENON: POP CULTURE, FANDOM, AND RELIGIOSITY IN CONTEMPORARY JAPAN By Kendra Nicole Sheehan B.A., University of Louisville, 2010 M.A., University of Louisville, 2012 A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the College of Arts and Sciences of the University of Louisville in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Humanities Department of Humanities University of Louisville Louisville, Kentucky December 2017 Copyright 2017 by Kendra Nicole Sheehan All rights reserved THE OTAKU PHENOMENON: POP CULTURE, FANDOM, AND RELIGIOSITY IN CONTEMPORARY JAPAN By Kendra Nicole Sheehan B.A., University of Louisville, 2010 M.A., University of Louisville, 2012 A Dissertation Approved on November 17, 2017 by the following Dissertation Committee: __________________________________ Dr. -

Capstone (1.134Mb)

Artist Statement: Ronald Fontenot (aka Scott C. Johnson) My art is heavily rooted in reflections of my childhood, my love for music, and my appreciation for nature and the natural world. In my childhood I was blessed with a loving family and pleasant experiences that I wish to share in some way with the viewer. Rather than simply tell stories or share memories, I try to create experiences that host the same energies and pleasantries I experienced for the viewer to enjoy. My hope is that this can be heard in my music, seen in my graphical work, and felt in my presentations. I also have a great respect for nature. From owning pets to growing plants to trips to the beach, mountains and zoo, I have always loved animals and find nature and plant life to be a great inspiration. I also find each season of the year to have its own unique beauty. With these things in mind, I gather resources that celebrate the natural world like photos and videos, to guide me in my art. I also find artists who agree with these sentiments and study their work. Finally, my work stands on the shoulders of music. Whether I am producing photos, logos, videos, animations, drawings, or my own songs, I find music moves me in what I do. I favor video game music mainly from classic games of the 90s from Japan. One of my favorite songs from a video game is "Nature's Breath" from the Samurai Shodown III soundtrack, a theme of the character Nakoruru who travels the game with a hawk and a wolf. -

1300 Games in 1 Games List

1300 Games in 1 Games List 1. 1942 – (Shooting) [609] 2. 1941 : COUNTER ATTACK – (Shooting) [608] 3. 1943 : THE BATTLE OF MIDWAY – (Shooting) [610] 4. 1943 KAI : MIDWAY KAISEN – (Shooting) [611] 5. 1944 : THE LOOP MASTER – (Shooting) [521] 6. 1945KIII – (Shooting) [604] 7. 19XX : THE WAR AGAINST DESTINY – (Shooting) [612] 8. 2020 SUPER BASEBALL – (Sport) [839] 9. 3 COUNT BOUT – (Fighting) [70] 10. 4 EN RAYA – (Puzzle) [1061] 11. 4 FUN IN 1 – (Shooting) [714] 12. 4-D WARRIORS – (Shooting) [575] 13. STREET : A DETECTIVE STORY – (Action) [303] 14. 88GAMES – (Sport) [881] 15. 9 BALL SHOOTOUT – (Sport) [850] 16. 99 : THE LAST WAR – (Shooting) [813] 17. D. 2083 – (Shooting) [768] 18. ACROBAT MISSION – (Shooting) [678] 19. ACROBATIC DOG-FIGHT – (Shooting) [735] 20. ACT-FANCER CYBERNETICK HYPER WEAPON – (Action) [320] 21. ACTION HOLLYWOOOD – (Action) [283] 22. AERO FIGHTERS – (Shooting) [673] 23. AERO FIGHTERS 2 – (Shooting) [556] 24. AERO FIGHTERS 3 – (Shooting) [557] 25. AGGRESSORS OF DARK KOMBAT – (Fighting) [64] 26. AGRESS – (Puzzle) [1054] 27. AIR ATTACK – (Shooting) [669] 28. AIR BUSTER : TROUBLE SPECIALTY RAID UNIT – (Shooting) [537] 29. AIR DUEL – (Shooting) [686] 30. AIR GALLET – (Shooting) [613] 31. AIRWOLF – (Shooting) [541] 32. AKKANBEDER – (Shooting) [814c] 33. ALEX KIDD : THE LOST STARS – (Puzzle) [1248] 34. ALIBABA AND 40 THIEVES – (Puzzle) [1149] 35. ALIEN CHALLENGE – (Fighting) [87] 36. ALIEN SECTOR – (Shooting) [718] 37. ALIEN STORM – (Action) [322] 38. ALIEN SYNDROME – (Action) [374] 39. ALIEN VS. PREDATOR – (Action) [251] 40. ALIENS – (Action) [373] 41. ALLIGATOR HUNT – (Action) [278] 42. ALPHA MISSION II – (Shooting) [563] 43. ALPINE SKI – (Sport) [918] 44. AMBUSH – (Shooting) [709] 45. -

Programmed Moves: Race and Embodiment in Fighting and Dancing Videogames

UC Berkeley UC Berkeley Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Programmed Moves: Race and Embodiment in Fighting and Dancing Videogames Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/5pg3z8fg Author Chien, Irene Y. Publication Date 2015 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Programmed Moves: Race and Embodiment in Fighting and Dancing Videogames by Irene Yi-Jiun Chien A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Film and Media and the Designated Emphasis in New Media in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Linda Williams, Chair Professor Kristen Whissel Professor Greg Niemeyer Professor Abigail De Kosnik Spring 2015 Abstract Programmed Moves: Race and Embodiment in Fighting and Dancing Videogames by Irene Yi-Jiun Chien Doctor of Philosophy in Film and Media Designated Emphasis in New Media University of California, Berkeley Professor Linda Williams, Chair Programmed Moves examines the intertwined history and transnational circulation of two major videogame genres, martial arts fighting games and rhythm dancing games. Fighting and dancing games both emerge from Asia, and they both foreground the body. They strip down bodily movement into elemental actions like stepping, kicking, leaping, and tapping, and make these the form and content of the game. I argue that fighting and dancing games point to a key dynamic in videogame play: the programming of the body into the algorithmic logic of the game, a logic that increasingly organizes the informatic structure of everyday work and leisure in a globally interconnected information economy. -

Master List of Games This Is a List of Every Game on a Fully Loaded SKG Retro Box, and Which System(S) They Appear On

Master List of Games This is a list of every game on a fully loaded SKG Retro Box, and which system(s) they appear on. Keep in mind that the same game on different systems may be vastly different in graphics and game play. In rare cases, such as Aladdin for the Sega Genesis and Super Nintendo, it may be a completely different game. System Abbreviations: • GB = Game Boy • GBC = Game Boy Color • GBA = Game Boy Advance • GG = Sega Game Gear • N64 = Nintendo 64 • NES = Nintendo Entertainment System • SMS = Sega Master System • SNES = Super Nintendo • TG16 = TurboGrafx16 1. '88 Games ( Arcade) 2. 007: Everything or Nothing (GBA) 3. 007: NightFire (GBA) 4. 007: The World Is Not Enough (N64, GBC) 5. 10 Pin Bowling (GBC) 6. 10-Yard Fight (NES) 7. 102 Dalmatians - Puppies to the Rescue (GBC) 8. 1080° Snowboarding (N64) 9. 1941: Counter Attack ( Arcade, TG16) 10. 1942 (NES, Arcade, GBC) 11. 1943: Kai (TG16) 12. 1943: The Battle of Midway (NES, Arcade) 13. 1944: The Loop Master ( Arcade) 14. 1999: Hore, Mitakotoka! Seikimatsu (NES) 15. 19XX: The War Against Destiny ( Arcade) 16. 2 on 2 Open Ice Challenge ( Arcade) 17. 2010: The Graphic Action Game (Colecovision) 18. 2020 Super Baseball ( Arcade, SNES) 19. 21-Emon (TG16) 20. 3 Choume no Tama: Tama and Friends: 3 Choume Obake Panic!! (GB) 21. 3 Count Bout ( Arcade) 22. 3 Ninjas Kick Back (SNES, Genesis, Sega CD) 23. 3-D Tic-Tac-Toe (Atari 2600) 24. 3-D Ultra Pinball: Thrillride (GBC) 25. 3-D WorldRunner (NES) 26. 3D Asteroids (Atari 7800) 27. -

![[Japan] SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1000 Miglia](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/3367/japan-sala-giochi-arcade-1000-miglia-393367.webp)

[Japan] SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1000 Miglia

SCHEDA NEW PLATINUM PI4 EDITION La seguente lista elenca la maggior parte dei titoli emulati dalla scheda NEW PLATINUM Pi4 (20.000). - I giochi per computer (Amiga, Commodore, Pc, etc) richiedono una tastiera per computer e talvolta un mouse USB da collegare alla console (in quanto tali sistemi funzionavano con mouse e tastiera). - I giochi che richiedono spinner (es. Arkanoid), volanti (giochi di corse), pistole (es. Duck Hunt) potrebbero non essere controllabili con joystick, ma richiedono periferiche ad hoc, al momento non configurabili. - I giochi che richiedono controller analogici (Playstation, Nintendo 64, etc etc) potrebbero non essere controllabili con plance a levetta singola, ma richiedono, appunto, un joypad con analogici (venduto separatamente). - Questo elenco è relativo alla scheda NEW PLATINUM EDITION basata su Raspberry Pi4. - Gli emulatori di sistemi 3D (Playstation, Nintendo64, Dreamcast) e PC (Amiga, Commodore) sono presenti SOLO nella NEW PLATINUM Pi4 e non sulle versioni Pi3 Plus e Gold. - Gli emulatori Atomiswave, Sega Naomi (Virtua Tennis, Virtua Striker, etc.) sono presenti SOLO nelle schede Pi4. - La versione PLUS Pi3B+ emula solo 550 titoli ARCADE, generati casualmente al momento dell'acquisto e non modificabile. Ultimo aggiornamento 2 Settembre 2020 NOME GIOCO EMULATORE 005 SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1 On 1 Government [Japan] SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1000 Miglia: Great 1000 Miles Rally SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 10-Yard Fight SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 18 Holes Pro Golf SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1941: Counter Attack SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1942 SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1943 Kai: Midway Kaisen SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1943: The Battle of Midway [Europe] SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1944 : The Loop Master [USA] SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1945k III SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 19XX : The War Against Destiny [USA] SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 2 On 2 Open Ice Challenge SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 4-D Warriors SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 64th. -

Comparatif Line up Neogeo Mini.Xlsx

Neo Geo Mini Samurai Showdown (40 jeux) Neo Geo Mini International (40 jeux) Neo Geo Mini Christmas (48 jeux) Neo Geo Asiatique (40 jeux) Agressor of Dark Combat 3 Count Bout Agressors of Dark Combat Aggressors of Dark Kombat Alpha Mission 2 Art of Fighting Alpha Mission 2 Alpha Mission II Art of Fighting Blazing Star Art of Fighting Art of Fighting Blazing Star Blue’s Journey Blazing Star Blazing Star Blue’s Journey Crossed Swords Blue’s Journey Burning Fight Burning Fight Fatal Fury Special Burning Fight Cyber-Lip Cyber Lip Foot Ball Frenzy Cyber Lip Fatal Fury Special Fatal Fury Garou : Mark of the Wolves Fatal Fury Garou : Mark of the Wolves Fatal Fury 2 Ghost Pilots Fatal Fury 2 King of Monsters 2 Garou : Mark of the Wolves King of the Monsters Fatal Fury 3 Kizuna Encounter : Super Tag Battle King of the Monsters 2 King of the Monsters 2 Garou : Mark of the Wolves Metal Slug Kizuna Encounter : Super Tag Battle Kizuna Encounter : Super Tag Battle King of the Monsters Metal Slug 2 League Bowling Last Resort King of the Monsters 2 Metal Slug 3 Magician Lord Magician Lord Kizuna Encounter : Super Tag Battle Ninja Commando Metal Slug Metal Slug League Bowling Ninja Master's : Haou Ninpou Chou Metal Slug 2 Metal Slug 2 Magician Lord Puzzled Metal Slug 3 Metal Slug 3 Metal Slug Real Bout Fatal Fury 2 : The Newcomers Ninja Combat Metal Slug 4 Metal Slug 2 Real Bout : Fatal Fury Ninja Master's : Haou Ninpou Chou Metal Slug 5 Metal Slug 3 Samurai Shodown II Real Bout : Fatal Fury 2 Metal Slug X Metal Slug 4 Samurai Shodown IV : Amakusa’s Revenge -

Gamewith / 6552

GameWith / 6552 COVERAGE INITIATED ON: 2019.09.27 LAST UPDATE: 2021.04.19 Shared Research Inc. has produced this report by request from the company discussed in the report. The aim is to provide an “owner’s manual” to investors. We at Shared Research Inc. make every effort to provide an accurate, objective, and neutral analysis. In order to highlight any biases, we clearly attribute our data and findings. We will always present opinions from company management as such. Our views are ours where stated. We do not try to convince or influence, only inform. We appreciate your suggestions and feedback. Write to us at [email protected] or find us on Bloomberg. Research Coverage Report by Shared Research Inc. GameWith / 6552 RCoverage LAST UPDATE: 2021.04.19 Research Coverage Report by Shared Research Inc. | https://sharedresearch.jp INDEX How to read a Shared Research report: This report begins with the trends and outlook section, which discusses the company’s most recent earnings. First-time readers should start at the business section later in the report. Executive summary ----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 3 Key financial data ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 5 Recent updates ---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 6 Highlights ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------ -

Fighting Games, Performativity, and Social Game Play a Dissertation

The Art of War: Fighting Games, Performativity, and Social Game Play A dissertation presented to the faculty of the Scripps College of Communication of Ohio University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy Todd L. Harper November 2010 © 2010 Todd L. Harper. All Rights Reserved. This dissertation titled The Art of War: Fighting Games, Performativity, and Social Game Play by TODD L. HARPER has been approved for the School of Media Arts and Studies and the Scripps College of Communication by Mia L. Consalvo Associate Professor of Media Arts and Studies Gregory J. Shepherd Dean, Scripps College of Communication ii ABSTRACT HARPER, TODD L., Ph.D., November 2010, Mass Communications The Art of War: Fighting Games, Performativity, and Social Game Play (244 pp.) Director of Dissertation: Mia L. Consalvo This dissertation draws on feminist theory – specifically, performance and performativity – to explore how digital game players construct the game experience and social play. Scholarship in game studies has established the formal aspects of a game as being a combination of its rules and the fiction or narrative that contextualizes those rules. The question remains, how do the ways people play games influence what makes up a game, and how those players understand themselves as players and as social actors through the gaming experience? Taking a qualitative approach, this study explored players of fighting games: competitive games of one-on-one combat. Specifically, it combined observations at the Evolution fighting game tournament in July, 2009 and in-depth interviews with fighting game enthusiasts. In addition, three groups of college students with varying histories and experiences with games were observed playing both competitive and cooperative games together.