Boom and Bust in the Waterberg a History of Coal Mega Projects

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

South Africa's Coalfields — a 2014 Perspective

International Journal of Coal Geology 132 (2014) 170–254 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect International Journal of Coal Geology journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/ijcoalgeo South Africa's coalfields — A 2014 perspective P. John Hancox a,⁎,AnnetteE.Götzb,c a University of the Witwatersrand, School of Geosciences and Evolutionary Studies Institute, Private Bag 3, 2050 Wits, South Africa b University of Pretoria, Department of Geology, Private Bag X20, Hatfield, 0028 Pretoria, South Africa c Kazan Federal University, 18 Kremlyovskaya St., Kazan 420008, Republic of Tatarstan, Russian Federation article info abstract Article history: For well over a century and a half coal has played a vital role in South Africa's economy and currently bituminous Received 7 April 2014 coal is the primary energy source for domestic electricity generation, as well as being the feedstock for the Received in revised form 22 June 2014 production of a substantial percentage of the country's liquid fuels. It furthermore provides a considerable source Accepted 22 June 2014 of foreign revenue from exports. Available online 28 June 2014 Based on geographic considerations, and variations in the sedimentation, origin, formation, distribution and quality of the coals, 19 coalfields are generally recognised in South Africa. This paper provides an updated review Keywords: Gondwana coal of their exploration and exploitation histories, general geology, coal seam nomenclature and coal qualities. With- Permian in the various coalfields autocyclic variability is the norm rather than the exception, whereas allocyclic variability Triassic is much less so, and allows for the correlation of genetically related sequences. During the mid-Jurassic break up Coalfield of Gondwana most of the coal-bearing successions were intruded by dolerite. -

Georesources and Environment Mining of the Waterberg

International Journal of IJGE 2018 4(3): 127-132 Georesources and Environment http://ijge.camdemia.ca, [email protected] Available at http://ojs.library.dal.ca/ijge Research and Development and Industry Mining of the Waterberg - a Unique Deposit Requiring Innovative Solutions Chabedi Kelello1*, Mhlongo Sifiso2 1 Department School of Mining Engineering, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, South Africa 2 Exxaro Grootegeluk Coal Mine, Lephalale Limpopo, South Africa Abstract: The Waterberg coalfield is a resource for the future contribution of energy in South Africa and has been marginally exploited to date. The coal deposit is technically unique and challenging. The carbonaceous nature of the overburden, interburden, the coal intercalations and discard makes it prone to spontaneous combustion. The coal has a high percentage of ash and low yields after beneficiation. Another unique feature of this coalfield is that it is a multi-seam coal deposit with a total of 13 benches occurring over a total thickness of 110m. Only one large open pit mine is currently in operation at the Grootegeluk Colliery despite the size of the resource. The mine has innovatively exploited the coal deposit profitability despite these challenges. Grootegeluk Colliery produces about 86 million tonnes ex-pit. The ROM produced in 2015 was about 54 million tonnes per annum (Mtpa) and the total waste produced was about 32 Mtpa making it one of the largest open pits in the history of South Africa. The paper discusses the state of the current mining and beneficiation techniques being used at the mine to exploit this vast reserve of the Waterberg coalfield which is the future coal supply of South Africa. -

Truth and Reconciliation Commission of South Africa Report: Volume 2

VOLUME TWO Truth and Reconciliation Commission of South Africa Report The report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission was presented to President Nelson Mandela on 29 October 1998. Archbishop Desmond Tutu Ms Hlengiwe Mkhize Chairperson Dr Alex Boraine Mr Dumisa Ntsebeza Vice-Chairperson Ms Mary Burton Dr Wendy Orr Revd Bongani Finca Adv Denzil Potgieter Ms Sisi Khampepe Dr Fazel Randera Mr Richard Lyster Ms Yasmin Sooka Mr Wynand Malan* Ms Glenda Wildschut Dr Khoza Mgojo * Subject to minority position. See volume 5. Chief Executive Officer: Dr Biki Minyuku I CONTENTS Chapter 1 Chapter 6 National Overview .......................................... 1 Special Investigation The Death of President Samora Machel ................................................ 488 Chapter 2 The State outside Special Investigation South Africa (1960-1990).......................... 42 Helderberg Crash ........................................... 497 Special Investigation Chemical and Biological Warfare........ 504 Chapter 3 The State inside South Africa (1960-1990).......................... 165 Special Investigation Appendix: State Security Forces: Directory Secret State Funding................................... 518 of Organisations and Structures........................ 313 Special Investigation Exhumations....................................................... 537 Chapter 4 The Liberation Movements from 1960 to 1990 ..................................................... 325 Special Investigation Appendix: Organisational structures and The Mandela United -

Class, Race and Gender Amongst White Volunteers, 1939-1953

From War to Workplace: Class, Race and Gender amongst White Volunteers, 1939-1953 By Neil Roos Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of History in the Faculty of Human and Social Sciences at the University of North West Supervisor: Dr. Tim Clynick Mafikeng, North West Province August 2001 To Dick Abstract Through a case study of the war and post-war experiences of those who volunteered to serve in the Second World War, the thesis explores aspects of the social and cultural history of white men in South Africa. The thesis begins from the premise that class and ethnicity, the major binary categories conventionally used to explain developments in white South African society, are unable to account for the history of white men who volunteered to serve in the Second World War. It argues that the history of these volunteers is best understood in the context of racist culture, which can be defined as an evolving consensus amongst whites in South Africa on the political, social and cultural primacy of whiteness. It argues that, when the call to arms came in 1939, it was answered mainly by white men from those little traditions incorporated politically into the segregationist colonial order, largely through the explicit emphases of white privilege and the cultural hegemony of whiteness. Their decision to enlist was underscored by an awareness that volunteering entailed a set of rights and duties, which centred on their expectations of post-war "social justice." Chapter three examines some of the highly idealised and implicitly racialised ways in which, during wartime, white troops expanded their understanding of social justice. -

Spatial Transformation: Are Intermediate Cities Different? South African Cities Network: Johannesburg

CENTRE FOR DEVELOPMENT SUPPORT SENTRUM VIR ONTWIKKELINGSTEUN ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Lead authors: Lochner Marais (University of the Free State) Danie Du Plessis (Stellenbosch University) Case study authors: Drakenstein: Ronnie Donaldson (Stellenbosch University) King Sabata Dalindyebo: Esethu Ndzamela (Nelson Mandela University) and Anton De Wit (Nelson Mandela University Lephalale: Kgosi Mocwagae (University of the Free State) Matjhabeng: Stuart Denoon-Stevens (University of the Free State) Mahikeng: Verna Nel (University of the Free State) and James Drummond (North West University) Mbombela: Maléne Campbell (University of the Free State) Msunduzi: Thuli Mphambukeli (University of the Free State) Polokwane: Gemey Abrahams (independent consultant) Rustenburg: John Ntema (University of South Africa) Sol Plaatje: Thomas Stewart (University of the Free State) Stellenbosch: Danie Du Plessis (Stellenbosch University) Manager: Geci Karuri-Sebina Editing by Write to the Point Design by Ink Design Photo Credits: Page 2: JDA/SACN Page 16: Edna Peres/SACN Pages 18, 45, 47, 57, 58: Steve Karallis/JDA/SACN Page 44: JDA/SACN Page 48: Tanya Zack/SACN Page 64: JDA/SACN Suggested citation: SACN. 2017. Spatial Transformation: Are Intermediate Cities Different? South African Cities Network: Johannesburg. Available online at www.sacities.net ISBN: 978-0-6399131-0-0 © 2017 by South African Cities Network. Spatial Transformation: Are Intermediate Cities Different? is made available under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/. 2 SPATIAL TRANSFORMATION: ARE INTERMEDIATE CITIES DIFFERENT? Foreword As a network whose primary stakeholders are the largest cities, the South African Cities Network (SACN) typically focuses its activities on the “big” end of the urban spectrum (essentially, mainly the metropolitan municipalities). -

Written Statement of Mxolisi Mgojo, the Chief Executive Officer Of

1 PUBLIC ENTERPRISES PORTFOLIO COMMITTEE INQUIRY INTO ESKOM, TRANSNET AND DENEL WRITTEN STATEMENT OF MXOLISI MGOJO, THE CHIEF EXECUTIVE OFFICER OF EXXARO RESOURCES LIMITED INTRODUCTION ...................................................................................................... 2 COST-PLUS MINES VERSUS COMMERCIAL MINES .......................................... 5 THE SO-CALLED “PRE-PAYMENT” FOR COAL ................................................. 9 PREJUDICE TO EXXARO’S COST-PLUS MINES AND MAFUBE ..................... 11 Introduction ........................................................................................................... 11 Arnot mine ............................................................................................................. 12 Eskom’s failure to fund land acquisition ................................................................. 12 Non-funding of operational capital at Arnot ............................................................ 14 The termination of Arnot’s CSA .............................................................................. 15 Conclusion of the Arnot matters ............................................................................. 19 Mafube mine.......................................................................................................... 19 Matla mine ............................................................................................................. 21 Non-funding of capital of R1.8 billion for mine 1 ................................................... -

The Role and Application of the Union Defence Force in the Suppression of Internal Unrest, 1912 - 1945

THE ROLE AND APPLICATION OF THE UNION DEFENCE FORCE IN THE SUPPRESSION OF INTERNAL UNREST, 1912 - 1945 Andries Marius Fokkens Thesis presented in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Military Science (Military History) at the Military Academy, Saldanha, Faculty of Military Science, Stellenbosch University. Supervisor: Lieutenant Colonel (Prof.) G.E. Visser Co-supervisor: Dr. W.P. Visser Date of Submission: September 2006 ii Declaration I, the undersigned, hereby declare that the work contained in this thesis is my own original work and that I have not previously submitted it, in its entirety or in part, to any university for a degree. Signature:…………………….. Date:………………………….. iii ABSTRACT The use of military force to suppress internal unrest has been an integral part of South African history. The European colonisation of South Africa from 1652 was facilitated by the use of force. Boer commandos and British military regiments and volunteer units enforced the peace in outlying areas and fought against the indigenous population as did other colonial powers such as France in North Africa and Germany in German South West Africa, to name but a few. The period 1912 to 1945 is no exception, but with the difference that military force was used to suppress uprisings of white citizens as well. White industrial workers experienced this military suppression in 1907, 1913, 1914 and 1922 when they went on strike. Job insecurity and wages were the main causes of the strikes and militant actions from the strikers forced the government to use military force when the police failed to maintain law and order. -

2. DESCRIPTION of the PROPOSED PROJECT In

Environmental Scoping Report for the proposed establishment of a New Coal-Fired Power Station in the Lephalale Area, Limpopo Province 2. DESCRIPTION OF THE PROPOSED PROJECT In order to be able to adequately provide for the growing electricity demand, Eskom propose to construct a new power station with a maximum capacity of 4 800 MegaWatts (MW) in the Lephalale area in the vicinity of the existing Matimba Power Station. Currently the project name for the new proposed power station is Matimba B, but the name will be changed should the project be approved. The power station will be coal-fired, and source coal from local coalfields. 2.1 The Proposed Matimba B Power Station Matimba B Power Station is proposed to ultimately have a maximum installed capacity of up to 4800 MW, but the first phase to be constructed and operated will be approximately half that installed capacity. The exact output will depend on the specification of the equipment installed and the ambient operating conditions. The footprint of the proposed new power station is still to be determined through final engineering and design, but has been indicated by Eskom that the new facility will be similar in size (ground footprint) to the existing Matimba Power Station. The power plant and associated plant (terrace area) would require an area of approximately 700 ha, and an additional approximate 500 - 1000 ha would be required for ancillary services, including ashing facilities (alternate ash disposal options are, however, currently being investigated). It is envisaged that the proposed power station will utilise a range of technologies pertaining to cooling, combustion and pollution abatement. -

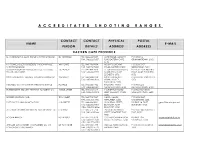

Accreditated Shooting Ranges

A C C R E D I T A T E D S H O O T I N G R A N G E S CONTACT CONTACT PHYSICAL POSTAL NAME E-MAIL PERSON DETAILS ADDRESS ADDRESS EASTERN CAPE PROVINCE D J SURRIDGE T/A ALOE RIDGE SHOOTING RANGE DJ SURRIDGE TEL: 046 622 9687 ALOE RIDGE MANLEY'S P O BOX 12, FAX: 046 622 9687 FLAT, EASTERN CAPE, GRAHAMSTOWN, 6140 6140 K V PEINKE (SOLE PROPRIETOR) T/A BONNYVALE WK PEINKE TEL: 043 736 9334 MOUNT COKE KWT P O BOX 5157, SHOOTING RANGE FAX: 043 736 9688 ROAD, EASTERN CAPE GREENFIELDS, 5201 TOMMY BOSCH AND ASSOCIATES CC T/A LOCK, T C BOSCH TEL: 041 484 7818 51 GRAHAMSTAD ROAD, P O BOX 2564, NOORD STOCK AND BARREL FAX: 041 484 7719 NORTH END, PORT EINDE, PORT ELIZABETH, ELIZABETH, 6056 6056 SWALLOW KRANTZ FIREARM TRAINING CENTRE CC WH SCOTT TEL: 045 848 0104 SWALLOW KRANTZ P O BOX 80, TARKASTAD, FAX: 045 848 0103 SPRING VALLEY, 5370 TARKASTAD, 5370 MECHLEC CC T/A OUTSPAN SHOOTING RANGE PL BAILIE TEL: 046 636 1442 BALCRAIG FARM, P O BOX 223, FAX: 046 636 1442 GRAHAMSTOWN, 6140 GRAHAMSTOWN, 6140 BUTTERWORTH SECURITY TRAINING ACADEMY CC WB DE JAGER TEL: 043 642 1614 146 BUFFALO ROAD, P O BOX 867, KING FAX: 043 642 3313 KING WILLIAM'S TOWN, WILLIAM'S TOWN, 5600 5600 BORDER HUNTING CLUB TE SCHMIDT TEL: 043 703 7847 NAVEL VALLEY, P O BOX 3047, FAX: 043 703 7905 NEWLANDS, 5206 CAMBRIDGE, 5206 EAST CAPE PLAINS GAME SAFARIS J G GREEFF TEL: 046 684 0801 20 DURBAN STREET, PO BOX 16, FORT [email protected] FAX: 046 684 0801 BEAUFORT, FORT BEAUFORT, 5720 CELL: 082 925 4526 BEAUFORT, 5720 ALL ARMS FIREARM ASSESSMENT AND TRAINING CC F MARAIS TEL: 082 571 5714 -

Literature Review: Public Health and Ecological Effects of Substances Emitted to Air from Power Plants Documents Published 2013-2020

REPORT Literature Review: Public Health and Ecological Effects of Substances Emitted to Air from Power Plants Documents Published 2013-2020 Submitted to: Katie Duffett, Project Manager, Clean Air Strategic Alliance 9915-108 Street NW, 1400 Edmonton, Alberta T5K 2G8 Submitted by: Golder Associates Ltd. Suite 200 - 2920 Virtual Way, Vancouver, British Columbia, V5M 0C4, Canada +1 604 296 4200 20397046-001-R-Rev0 18 March 2021 Classification: Protected A 18 March 2021 20397046-001-R-Rev0 Distribution List 1 e-copy Clean Air Strategic Alliance - Health and Environmental Assessment Task Group (HEAT Group) 1 e-copy Golder Associates Ltd. i Classification: Protected A 18 March 2021 20397046-001-R-Rev0 Executive Summary Golder Associates Ltd. (Golder) was retained by the Clean Air Strategic Alliance (CASA) to conduct a literature review on the public health and ecological effects of substances known to be emitted into the air from electricity generation using various resource types (e.g., coal, biomass, fuel oil, waste) from power plants (not limited to stack emissions). The objective of the literature review was to identify new information published from 2013 to 2020 to aid the 2018 Five-Year Review of the 2003 Emissions Management Framework for Alberta Electricity Sector. Golder conducted a search of white and grey literature for the literature review. White literature included primary peer-reviewed journal articles while grey literature included literature published by provincial, federal, and international organizations. Relevant articles were scored using the ‘Checklist for assessing the quality of quantitative studies' (herein referred to as the “Checklist”) developed at the Alberta Heritage Foundation for Medical Research1. -

Limpopo Water Management Area

LIMPOPO WATER MANAGEMENT AREA WATER RESOURCES SITUATION ASSESSMENT MAIN REPORT OVERVIEW The water resources of South Africa are vital to the health and prosperity of its people, the sustenance of its natural heritage and to its economic development. Water is a national resource that belongs to all the people who should therefore have equal access to it, and although the resource is renewable, it is finite and distributed unevenly both spatially and temporally. The water also occurs in many forms that are all part of a unitary and inter-dependent cycle. The National Government has overall responsibility for and authority over the nation’s water resources and their use, including the equitable allocation of water for beneficial and sustainable use, the redistribution of water and international water matters. The protection of the quality of water resources is also necessary to ensure sustainability of the nation’s water resources in the interests of all water users. This requires integrated management of all aspects of water resources and, where appropriate, the delegation of management functions to a regional or catchment level where all persons can have representative participation. This report is based on a desktop or reconnaissance level assessment of the available water resources and quality and also patterns of water requirements that existed during 1995 in the Limpopo Water Management Area, which occupies a portion of the Northern Province. The report does not address the water requirements beyond 1995 but does provide estimates of the utilisable potential of the water resources after so-called full development of these resources, as this can be envisaged at present. -

Annual Report 2011

Natural and Agricultural Sciences Annual Report 2011 Natural and Agricultural Sciences Annual Report 2011 Contact Details Dean Prof Neil Heideman +27 (0)51 401 2322 [email protected] Vice-Dean Prof. Corli Witthuhn +27 (0) 51 4013855 [email protected] Faculty Manager Mr Johan Kruger +27 (0)51 401 2409 Issued by [email protected] Faculty of Natural and Agricultural Sciences Marketing Manager University of the Free State Ms Elfrieda Lotter Editorial Compilation +27 (0)51 4012531 [email protected] Betta van Huyssteen Physical Address Language Revision Room 9A, Biology Building, Main Campus, Bloemfontein Betta van Huyssteen Stella Mcgill Postal Address Revision of Bibliographical Data University of the Free State PO Box 339 Mercia Coetzee Bloemfontein Design, Layout South Africa 9300 Chrysalis Advertising & Publishing Fax: +27 (0)51 401 3728 Printing E-mail: [email protected] Oranje Drukkery • Printers Faculty website: www.ufs.ac.za/natagri Table of Contents Preface 5 Research Clusters 6 Agricultural Sciences 13 Agricultural Economics 14 Animal, Wildlife and Grassland Sciences 20 Plant Sciences 30 Soil, Crop and Climate Sciences 40 Building Sciences 49 Architecture 50 Quantity Surveying and Construction Management 56 Urban and Regional Planning 62 Natural Sciences 67 Chemistry 68 Computer Science and Informatics 86 Consumer Science 94 Genetics 100 Geography 108 Geology 116 Mathematical Statistics and Actuarial Science 126 Mathematics and Applied Mathematics 132 Microbial, Biochemical and Food Biotechnology 136 Physics 150 Zoology