Second Standard Allocation Str

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Understanding Afghanistan

Understanding Afghanistan: The Importance of Tribal Culture and Structure in Security and Governance By Shahmahmood Miakhel US Institute of Peace, Chief of Party in Afghanistan Updated November 20091 “Over the centuries, trying to understand the Afghans and their country was turned into a fine art and a game of power politics by the Persians, the Mongols, the British, the Soviets and most recently the Pakistanis. But no outsider has ever conquered them or claimed their soul.”2 “Playing chess by telegraph may succeed, but making war and planning a campaign on the Helmand from the cool shades of breezy Shimla (in India) is an experiment which will not, I hope, be repeated”.3 Synopsis: Afghanistan is widely considered ungovernable. But it was peaceful and thriving during the reign of King Zahir Shah (1933-1973). And while never held under the sway of a strong central government, the culture has developed well-established codes of conduct. Shuras (councils) and Jirgas (meeting of elders) appointed through the consensus of the populace are formed to resolve conflicts. Key to success in Afghanistan is understanding the Afghan mindset. That means understanding their culture and engaging the Afghans with respect to the system of governance that has worked for them in the past. A successful outcome in Afghanistan requires balancing tribal, religious and government structures. This paper outlines 1) the traditional cultural terminology and philosophy for codes of conduct, 2) gives examples of the complex district structure, 3) explains the role of councils, Jirgas and religious leaders in governing and 4) provides a critical overview of the current central governmental structure. -

AFGHANISTAN POLIO SNAPSHOT SEPTEMBER 2018 6 POSITIVE ENVIRONMENT SAMPLES in SEPTEMBER Cases from Jan to Aug

3 WPV CASES IN SEPTEMBER 15 TOTAL WPV CASES IN 2018 AFGHANISTAN POLIO SNAPSHOT SEPTEMBER 2018 6 POSITIVE ENVIRONMENT SAMPLES IN SEPTEMBER Cases from Jan to Aug Cases in September 5.56m Jawzjan CHILDREN TARGETED IN SUB- Balkh Kunduz Takhar NATIONAL IMMUNIZATION DAYS Badakhshan Samangan GAZIABAD district Faryab Baghlan 2 WPV 5.04m Sar-e-Pul Panjsher Nuristan Badghis DOSES OF VACCINE GIVEN IN Bamyan Parwan CHAKWI district IMMUNIZATION DAYS Kunar Kabul KAMA district 1 WPV Wardak Hirat Ghor Nangarhar Logar 1 WPV Daykundi Paktya 48,800 Ghazni PACHIR-WA-AGAM district Khost FRONTLINE WORKERS 1 WPV (Overall 30% female:26.5% urban workers, 5% Uruzgan of rural) Farah Paktika SHAHID-E-HASSAS district Zabul 1 WPV SHAHWALIKOT district 7,000 Hilmand Kandahar 3 WPV SOCIAL MOBILIZERS Nimroz SPIN BOLDAK district (Overall 30% female) 1 WPV KANDAHAR city 484 NAD-E-ALI district 2 WPV PERMANENT TRANSIT TEAMS 1 WPV ARGHANDAB district 1 WPV 15 KHAKREZ district CROSS-BORDER VACCINATION 1 WPV POINTS Data as of 30 September 2018 WILD POLIOVIRUS CASE COUNT 2017-2018 POLIO TRANSMISSION • 3 new wild poliovirus (WPV1) cases were re- ported in September. 1 from Shahid-E-Hassas district of Uruzgan and 2 from Kandahar city of Kandahar province. • 6 WPV1 positive environmental samples were reported in September, all from Kandahar city of Kandahar province, bringing the total number of positive samples to 40 in 2018. AFP AND ENVIRONMENTAL SURVEILLANCE • 198 acute flaccid paralysis (AFP) cases (99 girls and 99 boys) reported in September. Overall in 2018, 2,451 AFP cases have been reported, of which 2,227 have been discarded as “non-polio AFP” and 209 cases are pending classification. -

Afghan Media in 2010

Afghan Media in 2010 Priority District Report Urgun (Paktika) October 13, 2010 This publication was produced for review by the United States Agency for International Development by Altai Consulting. The authors view expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect the views of the United States Agency for International Development or the United States Government. Afghan Media – Eight Years Later Priority District: Urgun (Paktika) Contents 1 INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................................... 3 1.1 DISTRICT PROFILE .......................................................................................................................................... 3 1.2 METHODOLOGY ............................................................................................................................................ 4 2 MEDIA LANDSCAPE ............................................................................................................................. 5 2.1 MEDIA OUTLETS ............................................................................................................................................ 5 2.1.1 Television ........................................................................................................................................ 5 2.1.2 Radio ............................................................................................................................................... 5 2.1.3 Newspapers ................................................................................................................................... -

·~~~I~Iiiiif~Imlillil~L~Il~Llll~Lif 3 ACKU 00000980 2

·~~~i~IIIIIf~imlillil~l~il~llll~lif 3 ACKU 00000980 2 OPERATION SALAM OFFICE OF THE UNITED NATIONS CO-ORDINATOR FOR HUMANITARIAN AND ECONOMIC ASSISTANCE PROGRAMMES RELATING TO AFGHANISTAN PROGRESS REPORT (JANUARY - APRIL 1990) ACKU GENEVA MAY 1990 Office of the Co-ordinator for United Nation Bureau du Coordonnateur des programmes Humanitarian and Economic Assistance d'assistance humanitaire et economique des Programmes relating to Afghanistan Nations Unies relatifs a I 1\fghanistan Villa La Pelouse. Palais des Nations. 1211 Geneva 10. Switzerland · Telephone : 34 17 37 · Telex : 412909 · Fa·x : 34 73 10 TABLE OF CONTENTS FOREWORD.................................................. 5 SECTORAL OVERVIEWS . 7 I) Agriculture . 7 II) Food Aid . 7 Ill) De-m1n1ng . 9 IV) Road repair . 9 V) Shelter . 10 VI) Power . 11 VII) Telecommunications . 11 VI II) Health . 12 IX) Water supply and sanitation . 14 X) Education . 15 XI) Vocational training . 16 XII) Disabled . 18 XIII) Anti-narcotics programme . 19 XIV) Culture . ACKU. 20 'W) Returnees . 21 XVI) Internally Displaced . 22 XVII) Logistics and Communications . 22 PROVINCIAL PROFILES . 25 BADAKHSHAN . 27 BADGHIS ............................................. 33 BAGHLAN .............................................. 39 BALKH ................................................. 43 BAMYAN ............................................... 52 FARAH . 58 FARYAB . 65 GHAZNI ................................................ 70 GHOR ................... ............................. 75 HELMAND ........................................... -

Paktika Province

UNHCR BACKGROUND REPORT PAKTIKA PROVINCE Prepared by the Data Collection for Afghan Repatriation Project 1 September 1989 PREFACE '!he follc,,.,ing report is one in a series of 14 provincial profiles prepared for the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees by the Data collec tion for Afghan Repatriation Project. '!he object of these reports is to provide detailed information on the conditions affecting the repatriation of Afghan refugees in each province so that UNHCRand its inplementing partners may be better able to plan and target progranunes of relief and rehabilitation assistance. Each of the provinces featured in this series is estimated to have at least 35 percent of its pre-1978 population living as refugees. Together, these 14 provinces -- Baghlan, Farah, Ghazni, Helmand, Herat, Kandahar, Kunar, I.aghman, Logar, Nangarhar, Nimroz, Paktia, Paktika and Zarul -- account for ninety percent of the Afghan refugee population settled in Iran and Pakistan. The Data collection for Afghan Repatriation Project (OCAR)was funded by UNHCRto develop a databr3se of information on Afghanistan that would serve as a resource for repatriation planning. Project staff based iJl Peshawar and Quetta have corrlucted interviews and surveys in refugee calTlpS through out NWFP,Baluchistan and Punjab provinces in Pakistan to compile data on refugee origins, ethnic and tribal affiliation and likely routes of refugee return to Afghanistan. In addition, the project field staff undertake frequent missions into Afghanistan to gather specific inform ation on road conditions, the availability of storage facilities, trans portation and fuel, the level of destruction of housing, irrigation systems and farmland, the location of landmines and the political and military situation at the district (woleswali)arrl sub-district (alagadari) levels in those provinces of priority concern to UNHCR. -

WHO Afghanistan Monthly Programme Update: September 2014 Emergency Humanitarian Action

WHO Afghanistan Monthly Programme Update: September 2014 Emergency Humanitarian Action KEY UPDATES: Emergency healthcare services for refugees from Paki- stan’s North Waziristan Agency (NWA) by Healthnet TPO and International Medical Corps (IMC) in Khost and Pak- tika continue: 23,828 patients were treated by mobile and static clinics in both provinces, including 14 deliver- ies and 6,704 routine vaccinations Conflict between Afghan National Security Forces (ANSF) and anti-government elements (AGE) escalated in Ghazni province, resulting in 568 Injuries and six deaths during September (according to provincial hos- pital records) From May 2013 to July 2014, 22,129 injuries were treated and 3,386 surgeries were performed under an ECHO- funded emergency trauma care project in Helmand Frederic Patigny from WHO runs a training Measles outbreaks continue to be a major concern for session on bacteriological testing of water under-5 morbidity and mortality in Afghanistan. 83 mea- in the field sles outbreaks have been reported by the Disease Early Warning System (DEWS) during the first nine months of 2014. A reactive vaccination campaign conducted by the Ministry of Public Health (MoPH), with technical and financial support from WHO and logistics support from UNICEF in July 2014 targeted 571,560 children in high-risk districts of high-risk provinces. The campaign had a pos- itive effect on the measles outbreak trend (see Graph 1) PROGRAMME ACTIVITIES AND ACHIEVEMENTS: WHO supported a training organized by Norplan on water testing in the field -

PFC Dudley of 1St Platoon, Comanche Company Pulls Se- Curity Along a Kalat Wall While on Patrol in Khost Province

geronimo journal PFC Dudley of 1st Platoon, Comanche Company pulls se- curity along a Kalat Wall while on patrol in Khost Province. Task Force 1-501 Family and Friends, We are at the hump, or maybe just over it, in terms of our deployment length, but there is still much to be done. We’re continuing to make progress in terms of Afghan forces being able to provide security; and these gains are opening the doors for significantly larger gains, progress begets progress. The willingness of our Afghan partners to take initiative in the planning and execution of operations is continually increasing. At the lower (Company/ PLT equivalent) level, our Afghan partner forces remain strong and competent. At the Kandak (Battalion equiva- lent) level and up they still face challenges, particularly in the area of logistic support. It is not for a lack of will, sometimes they’re just not sure how their own systems are supposed to work (a problem that can be found in our own Army). We have created some of this problem on our own over the past 10 years - supplying Afghan forces with whatever they need, as opposed to forcing their system to work. Our Security Force Assistance (SFA) Team (“Team Salakar”) is critical in helping our Afghan partners build their ability to supply themselves, communicate and synchronize operations across Khost Province. Team Salakar, in conjunction with our Companies, works con- stantly at various level to assist our Afghan partners in finding “Afghan solutions to Afghan problems.” We have completed the transition of Company Commanders in Easy and Blackfoot Companies, with CPT Adam Jones now at the helm of the FSC and CPT Matt Mobley leading Blackfoot Company at JCOP Chergowtah. -

AIHRC-UNAMA Joint Monitoring of Political Rights Presidential and Provincial Council Elections Third Report 1 August – 21 October 2009

Afghanistan Independent Human Rights Commission AIHRC AIHRC-UNAMA Joint Monitoring of Political Rights Presidential and Provincial Council Elections Third Report 1 August – 21 October 2009 United Nations Assistance Mission in Afghanistan UNAMA Table of Contents Summary of Findings i Introduction 1 I. Insecurity and Intimidation 1 Intensified violence and intimidation in the lead up to elections 1 Insecurity on polling day 2 II. Right to Vote 2 Insecurity and voting 3 Relocation or merging of polling centres and polling stations 4 Women’s participation 4 III. Fraud and Irregularities 5 Ballot box stuffing 6 Campaigning at polling stations and instructing voters 8 Multiple voter registration cards 8 Proxy voting 9 Underage voting 9 Deficiencies 9 IV. Freedom of Expression 9 V. Conclusion 10 Endnotes 11 Annex 1 – ECC Policy on Audit and Recount Evaluations 21 Summary of Findings The elections took place in spite of a challenging environment that was characterised by insecurity and logistical and human resource difficulties. These elections were the first to be fully led and organised by the Afghanistan Independent Election Commission (IEC) and the Afghan National Security Forces (ANSF) took the lead in providing security for the elections. It was also the first time that arrangements were made for prisoners and hospitalised citizens, to cast their votes. The steady increase of security-related incidents by Anti-Government Elements (AGEs) was a dominant factor in the preparation and holding of the elections. Despite commendable efforts from the ANSF, insecurity had a bearing on the decision of Afghans to participate in the elections Polling day recorded the highest number of attacks and other forms of intimidation for some 15 years. -

Today We Shall All Die” Afghanistan’S Strongmen and the Legacy of Impunity WATCH

HUMAN RIGHTS “Today We Shall All Die” Afghanistan’s Strongmen and the Legacy of Impunity WATCH “Today We Shall All Die” Afghanistan’s Strongmen and the Legacy of Impunity Copyright © 2015 Human Rights Watch All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America ISBN: 978-1-6231-32347 Cover design by Rafael Jimenez Human Rights Watch defends the rights of people worldwide. We scrupulously investigate abuses, expose the facts widely, and pressure those with power to respect rights and secure justice. Human Rights Watch is an independent, international organization that works as part of a vibrant movement to uphold human dignity and advance the cause of human rights for all. Human Rights Watch is an international organization with staff in more than 40 countries, and offices in Amsterdam, Beirut, Berlin, Brussels, Chicago, Geneva, Goma, Johannesburg, London, Los Angeles, Moscow, Nairobi, New York, Paris, San Francisco, Sydney, Tokyo, Toronto, Tunis, Washington DC, and Zurich. For more information, please visit our website: http://www.hrw.org MARCH 2015 ISBN: 978-1-6231-32347 “Today We Shall All Die” Afghanistan’s Strongmen and the Legacy of Impunity Map .................................................................................................................................... i Glossary of Acronyms and Terms ........................................................................................ ii Summary .......................................................................................................................... -

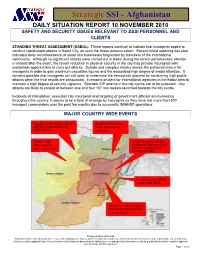

Daily Situation Report 10 November 2010 Safety and Security Issues Relevant to Sssi Personnel and Clients

Strategic SSI - Afghanistan DAILY SITUATION REPORT 10 NOVEMBER 2010 SAFETY AND SECURITY ISSUES RELEVANT TO SSSI PERSONNEL AND CLIENTS STANDING THREAT ASSESSMENT (KABUL): Threat reports continue to indicate that insurgents aspire to conduct coordinated attacks in Kabul City, as such the threat remains extant. Recent threat reporting has also indicated likely reconnaissance of areas and businesses frequented by members of the international community. Although no significant attacks were carried out in Kabul during the recent parliamentary election, or indeed after the event, the recent reduction in physical security in the city may provide insurgents with exploitable opportunities to carry out attacks. Suicide and complex attacks remain the preferred choice for insurgents in order to gain maximum casualties figures and the associated high degree of media attention. It remains possible that insurgents will still seek to undermine the democratic process by conducting high profile attacks when the final results are announced. It remains prudent for international agencies in the Kabul area to maintain a high degree of security vigilance. Sporadic IDF attacks in the city centre are to be expected. Any attacks are likely to consist of between one and four 107 mm rockets launched towards the city centre. Incidents of intimidation, executions by insurgents and targeting of government officials are increasing throughout the country. It seems to be a form of revenge by insurgents as they have lost more than 300 insurgent commanders over the past -

Khost Province

AFGHANISTAN Khost Province District Atlas April 2014 Disclaimers: The designations employed and the presentation of material on this map do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Secretariat of the United Nations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. http://afg.humanitarianresponse.info [email protected] AFGHANISTAN: Khost Province Reference Map 69°30'0"E 70°0'0"E Legend ^! Capital Ahmadaba District Lija Ahmad Khel Chamkani Dand Wa !! Provincial Center / Laja Mangel District Patan Sayedkaram ! ! District District District Center Paktya Administrative Boundaries Province International Province Sayedkaram Janikhel Distirict / Mirzaka ! Janikhel Jajimaydan District District District Transportation Kurram Musakhel ! Jajimaydan Agency Primary Road District Secondary Road o Airport Sabari ! p Airfield Sabari District River/Stream Gardez Musakhel River/Lake District ! Bak ! Bak District Qalandar 33°30'0"N 33°30'0"N District Shawak Qalandar District ! Zadran District Shawak ! Terezayi ! Khost Terezayi District Date Printed: 30 March 2014 08:40 AM Zadran Nadirshahkot ! Province District Data Source(s): AGCHO, CSO, AIMS, MISTI p Schools - Ministry of Education ° Khost (Matun) Health Facilities - Ministry of Health !! p Projection/Datum: Geographic/WGS-84 Shamal Shamal Nadirshahkot Khost (Matun) ! ! District ! District 0 20 Kms Mandozayi Mandozayi Gurbuz ! District Disclaimers: The designations employed and the presentation of material on this map do not imply the expression of any opinion ! whatsoever on the part of the Secretariat of the United Tani Nations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. -

Afghanistan Weekly Field Report 11,800 27,700 75,643

Afghanistan Weekly Field Report 23 - 29 April 2018 Key issues in the past week: • Nearly 12,000 people have been newly displaced in Afghanistan, according to initial reports. • Fighting reportedly displaced around 2,100 people in Paktika and 1,400 in Badakhshan. • Flash floods in Takhar Province reportedly destroyed an estimated 50 houses. • Around 2,900 people who had been displaced due to the drought received humanitarian aid in Hirat. 11,800 27,700 75,643 New IDPs reported People assisted in Total IDPs in 2018 in the past week the past week Displacement alerts received in the past week from authorities and partners. Countrywide conflict displacement The nearly 2,900 people who were displaced two weeks ago from Badghis to Hirat due to the drought received food rations, A total of 75,643 people have been displaced by conflict since NFIs and emergency shelter from humanitarian partners. the beginning of the year, according to OCHA’s Displacement Tracking System (DTS), up by nearly 3,000 people compared Returns to Afghanistan to the previous week. From 22 to 28 April, a total of 21,337 Afghan citizens returned Displacement Alerts (see map) to their home country. Following displacement alerts are shared based on initial According to IOM, 1,150 people returned spontaneously from information from authorities or partners on the ground. Pakistan and 32 more were deported. From Iran, 10,290 people Numbers can change as more information becomes available. returned on their own and 10,211 were deported. The returns from Iran in April were markedly higher than compared to the Central, Capital & South-Eastern Region: Around 2,100 same month a year ago, notably due to fewer work people reportedly arrived in Urgun district and 400 in Sharan, opportunities in Iran caused by the devaluation of the Iranian Paktika, from three districts within the province, due to armed currency and increased pressure on migrants in Iran.