Lessons Learned from Stabilization Initiatives in Afghanistan: a Systematic Review of Existing Research

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Progress in Afghanistan Bucharest Summit2-4 April 2008 Progress in Afghanistan

© MOD NL © MOD Canada © MOD Canada Progress in Afghanistan Progress in Bucharest Summit 2-4 April 2008 Bucharest Summit2-4 Progress in Afghanistan Contents page 1. Foreword by Assistant Secretary General for Public Diplomacy, ..........................1 Jean-François Bureau, and NATO Spokesman, James Appathurai 2. Executive summary .........................................................................................................................................2 3. Security ..................................................................................................................................................................... 4 • IED attacks and Counter-IED efforts 4 • Musa Qala 5 • Operations Medusa successes - Highlights Panjwayi and Zhari 6 • Afghan National Army 8 • Afghan National Police 10 • ISAF growth 10 4. Reconstruction and Development ............................................................................................... 12 • Snapshots of PRT activities 14 • Afghanistan’s aviation sector: taking off 16 • NATO-Japan Grant Assistance for Grassroots Projects 17 • ISAF Post-Operations Humanitarian Relief Fund 18 • Humanitarian Assistance - Winterisation 18 5. Governance ....................................................................................................................................................... 19 • Counter-Narcotics 20 © MOD Canada Foreword The NATO-led International Security Assistance Force (ISAF) mission is approaching five years of operations in Afghanistan. This report is a -

Sunday, 06 October 2019 Venue: FAO Meeting Room Draft Agenda

Time: 14:00 – 15:30 hrs Date: Sunday, 06 October 2019 Venue: FAO Meeting Room Draft Agenda: Introduction of ANDMA Nangarhar Newly appointed Director Update on the current humanitarian situation in Nurgal (Kunar) and Surkhrod (Nangarhar) – DoRR, OCHA Petition from Surkhrod for Tents and IDPs left of assessment Update on the status of Joint Needs Assessment & Response – OCHA and Partners Petitions for IDPs from Laghman AOB www.unocha.org The mission of the United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) is to mobilize and coordinate effective and principled humanitarian action in partnership with national and international actors. Coordination Saves Lives Update on Assessment & Response on Natural disasters – as of 21 April 2019 - IOM & ANDMA Deaths In Responde Province Districts Affected & Initial Info. # of Families Agencies Agencies Response Assistance Action Points j Status Assessed Families ured Assessed Assessed Responde Provided Affected d d Nangarhar 250 (1817 9 5 250 and 105 IOM, IMC, IOM, Ongoing NFI, Tents, -Health MHT will be deployed Assessment individuals) Assessment ongoing WFP, SCI, effective 23 April 2019.4.22, completed in Lalpur, NCRO, Pending: food, Kama, Rodat, Behsud, OXFAM, -WASH cluster will reassess the Jalalabad city, Goshta, RRD, ARCS, needs and respond accordingly. Mohmandara, Kot, Bati DACAAR, Kot DAIL, DA -IOM to share the list of families recommended for permanent Assessment ongoing: shelter with ACTED. Shirzad, Dehbala, Pachir- Agam, -ANDMA will clarify the land Chaparhar, -

A Day-To-Day Chronicle of Afghanistan's Guerrilla and Civil

A Day-to-Day Chronicle of Afghanistan's Guerrilla © and Civil War, June 2003 – Present Memories of Vietnam? A Chinook helicopter extracts troops of the 10th Vietnam epiphany. U.S. troops on patrol in the Afghan countryside, April 2003 Mountain Division in Nov. 2003 in Kunar province (photo by Sgt. Greg Heath, [photo in World News Network 5/2/03]. For more on parallels with Vietnam, see 4th Public Affairs Dept., Nov. 2003). Ian Mather, "Soldiers Fear 'Afghan Vietnam'," The Scotsman [May 4, 2003] A new file was begun after May 31, 2003 for two reasons: (1). during May, Secretary Rumsfeld announced the end of major U.S. combat operations in Afghanistan; and (2) in June, Mullah Omar announced a new 10-man leadership council of the Taliban and urged an increased guerrilla warfare. The new data set better captures the extent of this civil and guerrilla conflict. "...we're at a point where we clearly have moved from major combat activity to a period of stability and stabilization and reconstruction activities...." Spoken by Secretary Rumsfeld in Kabul on May 1, 2003 True or False? On August 22, 2002, the U.S. 82nd Airborne carried out another helicopter assault in Paktia province as part of a week-long campaign, 'Operation Mountain Sweep.' 1 Copyright © 2004 Marc W. Herold Estimated Number of Afghan Civilian "Impact Deaths1” Period Low Count High Count Oct. 2001 - May 2003 * 3,073 3,597 June 2003 – June 2004 412 437 CIVILIAN CASUALTIES TOTAL 3,485 4,034 * Source: “The Daily Casualty Count of Afghan Civilians Killed by U.S. -

Alizai Durrani Pashtun

Program for Culture & Conflict Studies www.nps.edu/programs/ccs Khugiani Clan Durrani Pashtun Pashtun Duranni Panjpai / Panjpal / Panjpao Khugiani (Click Blue box to continue to next segment.) Reference: Courage Services Inc., Tribal Hierarchy & Dictionary of Afghanistan: A Reference Aid for Analysts, (February 2007). Adamec, Ludwig, Historical and Political Gazetteer of Afghanistan, Vol. 6, 1985. Program for Culture & Conflict Studies www.nps.edu/programs/ccs Khugiani Clan Durrani Pashtuns Khugiani Gulbaz Khyrbun / Karbun Khabast Sherzad Kharbun / Khairbun Wazir / Vaziri / Laili (Click Blue box to continue to next segment.) Kharai Najibi Reference: Courage Services Inc., Tribal Hierarchy & Dictionary of Afghanistan: A Reference Aid for Analysts, (February 2007). Adamec, Ludwig, Historical and Political Gazetteer of Afghanistan, Vol. 6, 1985. Program for Culture & Conflict Studies www.nps.edu/programs/ccs Khyrbun / Karbun Khugiani Clan Khyrbun / Karbun Karai/ Garai/ Karani Najibi Ghundi Mukar Ali Mando Hamza Paria Api Masto Jaji / Jagi Tori Daulat Khidar Motik Reference: Courage Services Inc., Tribal Hierarchy & Dictionary of Afghanistan: A Reference Aid for Analysts, (February 2007). Adamec, Ludwig, Historical and Political Gazetteer of Afghanistan, Vol. 6, 1985. Program for Culture & Conflict Studies www.nps.edu/programs/ccs Sherzad Khugiani Clan Sherzad Dopai Marki Khodi Panjpai Lughmani Shadi Mama Reference: Courage Services Inc., Tribal Hierarchy & Dictionary of Afghanistan: A Reference Aid for Analysts, (February 2007). Adamec, Ludwig, Historical and Political Gazetteer of Afghanistan, Vol. 6, 1985. Program for Culture & Conflict Studies www.nps.edu/programs/ccs Wazir / Vaziri / Laili Khugiani Clan Wazir / Vaziri / Laili Motik / Motki Sarki / Sirki Ahmad / Ahmad Khel Pira Khel Agam / Agam Khel Nani / Nani Khel Kanga Piro Barak Rani / Rani Khel Khojak Taraki Bibo Khozeh Khel Reference: Courage Services Inc., Tribal Hierarchy & Dictionary of Afghanistan: A Reference Aid for Analysts, (February 2007). -

AFGHANISTAN - Base Map KYRGYZSTAN

AFGHANISTAN - Base map KYRGYZSTAN CHINA ± UZBEKISTAN Darwaz !( !( Darwaz-e-balla Shaki !( Kof Ab !( Khwahan TAJIKISTAN !( Yangi Shighnan Khamyab Yawan!( !( !( Shor Khwaja Qala !( TURKMENISTAN Qarqin !( Chah Ab !( Kohestan !( Tepa Bahwddin!( !( !( Emam !( Shahr-e-buzorg Hayratan Darqad Yaftal-e-sufla!( !( !( !( Saheb Mingajik Mardyan Dawlat !( Dasht-e-archi!( Faiz Abad Andkhoy Kaldar !( !( Argo !( Qaram (1) (1) Abad Qala-e-zal Khwaja Ghar !( Rostaq !( Khash Aryan!( (1) (2)!( !( !( Fayz !( (1) !( !( !( Wakhan !( Khan-e-char Char !( Baharak (1) !( LEGEND Qol!( !( !( Jorm !( Bagh Khanaqa !( Abad Bulak Char Baharak Kishim!( !( Teer Qorghan !( Aqcha!( !( Taloqan !( Khwaja Balkh!( !( Mazar-e-sharif Darah !( BADAKHSHAN Garan Eshkashem )"" !( Kunduz!( !( Capital Do Koh Deh !(Dadi !( !( Baba Yadgar Khulm !( !( Kalafgan !( Shiberghan KUNDUZ Ali Khan Bangi Chal!( Zebak Marmol !( !( Farkhar Yamgan !( Admin 1 capital BALKH Hazrat-e-!( Abad (2) !( Abad (2) !( !( Shirin !( !( Dowlatabad !( Sholgareh!( Char Sultan !( !( TAKHAR Mir Kan Admin 2 capital Tagab !( Sar-e-pul Kent Samangan (aybak) Burka Khwaja!( Dahi Warsaj Tawakuli Keshendeh (1) Baghlan-e-jadid !( !( !( Koran Wa International boundary Sabzposh !( Sozma !( Yahya Mussa !( Sayad !( !( Nahrin !( Monjan !( !( Awlad Darah Khuram Wa Sarbagh !( !( Jammu Kashmir Almar Maymana Qala Zari !( Pul-e- Khumri !( Murad Shahr !( !( (darz !( Sang(san)charak!( !( !( Suf-e- (2) !( Dahana-e-ghory Khowst Wa Fereng !( !( Ab) Gosfandi Way Payin Deh Line of control Ghormach Bil Kohestanat BAGHLAN Bala !( Qaysar !( Balaq -

Positive Deviance Research Report Jan2014

FutureGenerations Afghanistan . empowering communities to shape their futures ________________________________________________________________________________ Research Report Engaging Community Resilience for Security, Development and Peace building in Afghanistan ________________________________________________________________________________ December 2013 Funding Agencies United State Institute of Peace Rockefeller Brothers Fund Carnegie Corporation of New York Contact House # 115, 2nd Str., Parwan-2, Kabul, Afghanistan Cell: +93 (0) 799 686 618 / +93 (0) 707 270 778 Email: [email protected] Website: www.future.org 1 Engaging Community Resilience for Security, Development and Peacebuilding in Afghanistan Project Research Report Table of Contents List of Table List of Figures and Maps List of Abbreviations Glossary of local Language Words Chapter Title Page INTRODUCTION 3 Positive Deviance Process Conceptual Framework 4 • Phase-1: Inception • Phase-2: Positive Deviance Inquiry • Phase-3: Evaluation SECTION-1: Inception Phase Report 7 Chapter One POSITIVE DEVIANCE HISTORY AND DEFINITIONS 7 History 7 Definitions (PD concept, PD approach, PD inquiry, PD process, PD 8 methodology) a) Assessment Phase: Define, Determine, Discover 8 b) Application Phase: Design, Discern, Disseminate 9 Positive Deviance Principles 10 When to use positive deviance 10 Chapter Two RESEARCH CONTEXT 11 Challenges 11 Study Objectives 12 Site Selection 13 Research Methods 13 Composite Variables and Data Analysis 14 Scope and Limitation 15 Chapter Three SOCIO-POLITICAL -

The Impact of Explosive Weapons on Education: a Case Study of Afghanistan

The Impact of Explosive Weapons on Education: A Case Study of Afghanistan Students in their classroom in Zhari district, Khandahar province, Afghanistan. Many of the school’s September 2021 buildings were destroyed in airstrikes, leaving classrooms exposed. © 2019 Stefanie Glinski The Impact of Explosive Weapons on Education: A Case Study of Afghanistan Summary Between January 2018 and June 2021, the Global Coalition to Protect Education from Attack (GCPEA) identified over 200 reported attacks on schools, school students and personnel, and higher education in Afghanistan that involved explosive weapons. These attacks injured or killed hundreds of students and educators and damaged or destroyed dozens of schools and universities. In the first six months of 2021, more attacks on schools using explosive weapons were reported than in the first half of any of the previous three years. Explosive weapons were used in an increasing proportion of all attacks on education since 2018, with improvised explo- sive devices most prevalent among these attacks. Attacks with explosive weapons also caused school closures, including when non-state armed groups used explosive weapons to target girls’ education. Recommendations • Access to education should be a priority in Afghanistan, and schools and universities, as well as their students and educators, should be protected from attack. • State armed forces and non-state armed groups should avoid using explosive weapons with wide-area effects in populated areas, including near schools or universities, and along routes to or from them. • When possible, concerned parties should make every effort to collect and share disaggregat- ed data on attacks on education involving explosive weapons, so that the impact of these attacks can be better understood, and prevention and response measures can be devel- oped. -

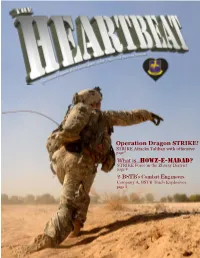

Operation Dragon STRIKE! What Is...Howz-E-Madad? 2-BSTB's Combat Engineers

Operation Dragon STRIKE! STRIKE Attacks Taliban with offensive page7 What is...Howz-E-Madad? STRIKE Force in the Zharay District page 9 2-BSTB’s Combat Engineers Company A, BSTB Teach Explosives page 5 Table of Contents... 2 COLUMNS 2 Words From the Top A message to the reader from STRIKE’s Leaders, 5 Col. Arthur Kandarian and Sgt. Maj. John White. 3 The Brigade’s Surgeon & Chaplain Direction provided by the Lt. Col. Michael Wirt and Maj. David Beavers. 4 Combat Stress, The Mayor & Safety 6 Guidance, direction and standards. FEATURES 5 Engineers, Infantry & Demolition 7 2-BSTB’s Alpha Company teaches the line units explosives 6 ANA gets behind the wheel Soldiers send the ANA through driver’s training Coverpage!! 7 Operation Dragon STRIKE Combined Task Force STRIKE attacksTaliban. 9 9 What is… Howz-E-Madad? A look at STRIKE Force and its Foward Operating Base. Staff Sgt. James Leach, a platoon 11 Company D, 2nd Five-Oh-Deuce sergeant with 1/75’s HHT, points Dog Company stays together during deploying. at enemy positions while in a fire fight during an objective for Opera- STRIKE SPECIALS tion Dragon STRIKE 13 Faces of STRIKE Snap-shots of today’s STRIKE Soldiers 11 14 We Will Never Forget STRIKE honors its fallen. 13 CONTRIBUTORS OIC Maj. Larry Porter Senior Editor Sfc. William Patterson Editor Spc. Joe Padula 14 Staff Spc. Mike Monroe Staff Pfc. Shawn Denham The Heartbeat is published monthly by the STRIKE BCT Public Affairs Office, FOB Wilson, Afghanistan, APO AE 09370. In accordance with DoD Instruction 5120.4 the HB is an authorized publication of the Department of Defense. -

19 October 2020 "Generated on Refers to the Date on Which the User Accessed the List and Not the Last Date of Substantive Update to the List

Res. 1988 (2011) List The List established and maintained pursuant to Security Council res. 1988 (2011) Generated on: 19 October 2020 "Generated on refers to the date on which the user accessed the list and not the last date of substantive update to the list. Information on the substantive list updates are provided on the Council / Committee’s website." Composition of the List The list consists of the two sections specified below: A. Individuals B. Entities and other groups Information about de-listing may be found at: https://www.un.org/securitycouncil/ombudsperson (for res. 1267) https://www.un.org/securitycouncil/sanctions/delisting (for other Committees) https://www.un.org/securitycouncil/content/2231/list (for res. 2231) A. Individuals TAi.155 Name: 1: ABDUL AZIZ 2: ABBASIN 3: na 4: na ﻋﺒﺪ اﻟﻌﺰﻳﺰ ﻋﺒﺎﺳﯿﻦ :(Name (original script Title: na Designation: na DOB: 1969 POB: Sheykhan Village, Pirkowti Area, Orgun District, Paktika Province, Afghanistan Good quality a.k.a.: Abdul Aziz Mahsud Low quality a.k.a.: na Nationality: na Passport no: na National identification no: na Address: na Listed on: 4 Oct. 2011 (amended on 22 Apr. 2013) Other information: Key commander in the Haqqani Network (TAe.012) under Sirajuddin Jallaloudine Haqqani (TAi.144). Taliban Shadow Governor for Orgun District, Paktika Province as of early 2010. Operated a training camp for non- Afghan fighters in Paktika Province. Has been involved in the transport of weapons to Afghanistan. INTERPOL- UN Security Council Special Notice web link: https://www.interpol.int/en/How-we-work/Notices/View-UN-Notices- Individuals click here TAi.121 Name: 1: AZIZIRAHMAN 2: ABDUL AHAD 3: na 4: na ﻋﺰﯾﺰ اﻟﺮﺣﻤﺎن ﻋﺒﺪ اﻻﺣﺪ :(Name (original script Title: Mr Designation: Third Secretary, Taliban Embassy, Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates DOB: 1972 POB: Shega District, Kandahar Province, Afghanistan Good quality a.k.a.: na Low quality a.k.a.: na Nationality: Afghanistan Passport no: na National identification no: Afghan national identification card (tazkira) number 44323 na Address: na Listed on: 25 Jan. -

Hajji Din Mohammad Biography

Program for Culture & Conflict Studies www.nps.edu/programs/ccs Hajji Din Mohammad Biography Hajji Din Mohammad, a former mujahedin fighter from the Khalis faction of Hezb-e Islami, became governor of the eastern province of Nangarhar after the assassination of his brother, Hajji Abdul Qadir, in July 2002. He is also the brother of slain commander Abdul Haq. He is currently serving as the provincial governor of Kabul Province. Hajji Din Mohammad’s great-grandfather, Wazir Arsala Khan, served as Foreign Minister of Afghanistan in 1869. One of Arsala Khan's descendents, Taj Mohammad Khan, was a general at the Battle of Maiwand where a British regiment was decimated by Afghan combatants. Another descendent, Abdul Jabbar Khan, was Afghanistan’s first ambassador to Russia. Hajji Din Mohammad’s father, Amanullah Khan Jabbarkhel, served as a district administer in various parts of the country. Two of his uncles, Mohammad Rafiq Khan Jabbarkhel and Hajji Zaman Khan Jabbarkhel, were members of the 7th session of the Afghan Parliament. Hajji Din Mohammad’s brothers Abdul Haq and Hajji Abdul Qadir were Mujahedin commanders who fought against the forces of the USSR during the Soviet Occupation of Afghanistan from 1980 through 1989. In 2001, Abdul Haq was captured and executed by the Taliban. Hajji Abdul Qadir served as a Governor of Nangarhar Province after the Soviet Occupation and was credited with maintaining peace in the province during the years of civil conflict that followed the Soviet withdrawal. Hajji Abdul Qadir served as a Vice President in the newly formed post-Taliban government of Hamid Karzai, but was assassinated by unknown assailants in 2002. -

Afghanistan Security Situation in Nangarhar Province

Report Afghanistan: The security situation in Nangarhar province Translation provided by the Office of the Commissioner General for Refugees and Stateless Persons, Belgium. Report Afghanistan: The security situation in Nangarhar province LANDINFO – 13 OCTOBER 2016 1 About Landinfo’s reports The Norwegian Country of Origin Information Centre, Landinfo, is an independent body within the Norwegian Immigration Authorities. Landinfo provides country of origin information to the Norwegian Directorate of Immigration (Utlendingsdirektoratet – UDI), the Immigration Appeals Board (Utlendingsnemnda – UNE) and the Norwegian Ministry of Justice and Public Security. Reports produced by Landinfo are based on information from carefully selected sources. The information is researched and evaluated in accordance with common methodology for processing COI and Landinfo’s internal guidelines on source and information analysis. To ensure balanced reports, efforts are made to obtain information from a wide range of sources. Many of our reports draw on findings and interviews conducted on fact-finding missions. All sources used are referenced. Sources hesitant to provide information to be cited in a public report have retained anonymity. The reports do not provide exhaustive overviews of topics or themes, but cover aspects relevant for the processing of asylum and residency cases. Country of origin information presented in Landinfo’s reports does not contain policy recommendations nor does it reflect official Norwegian views. © Landinfo 2017 The material in this report is covered by copyright law. Any reproduction or publication of this report or any extract thereof other than as permitted by current Norwegian copyright law requires the explicit written consent of Landinfo. For information on all of the reports published by Landinfo, please contact: Landinfo Country of Origin Information Centre Storgata 33A P.O. -

Contents EDITORIAL, POLITICAL ANALYSIS, 3 a Quarterly Publication of MILITARY REPORT

AECHAN JEHAD Contents EDITORIAL, POLITICAL ANALYSIS, 3 A Quarterly Publication of MILITARY REPORT, The Cultural Council of Grand table of Afghanwar casualties Afghanistan Resistance (April -June, 1988) Afghans and the Geneva accordon Afghanistan 14 MANAGING EDITOR: ® MAJOR DOCUMENTS: 21 Sabahuddin Kushkaki 1. Text of charter for mujaheddin transitional April-June, 1908 government; (2) Text of Geneva accord on Afghan- istan; (3) IUAM and the Geneva accord; (4) Muja- SUBSCRIPTION heddin offer general amnesty; (5) IUAM President urges trial for PDPA high brass; (6) Biographies Per Six Annual of IUAM transitional cabinet; (7) Biographies of copy months three IUAM leaders; (8) Charters of the IUAM Pakistaa organizations; (9) Annual report of Amnesty In- (Ra.) 30 60 110 ternational on Afghanistan, Foreign AFUHANISTAN IN INTERNATIONAL FORUMS: (s) 6 12 30 1« Islamabad Conference on Afghan future 2. Karachi Islamic meeting 3. Paris Conference: Afghan Agriculture Cultural Council of Afghanist- 0 IRC Survey on health in Afghan refugeecamps.97 Resistance CATALOGUE OF MUJAHEDDIN PRESS House No.8861 St. No. 27, G /9 -1 99 103 Islamabad, Pakistan 0 DIGEST OF MUJAHEDDIN PRESS Telephone 853797 (APRIL-JUNE 1988) ® BOOKS BY THE MUJAHEDDIN, FOR THE 164 MUJAHEDDIN 0 CHRONOLOGY OF AFGHAN EVENTS 168 (APRIL-JUNE 1988) 0 AFGHAN ISSUES COVERAGE: 318 By Radio Kabul, Radio Moscow (April -June, 1988) 0 MAPS 319 -320 0 ABBREVIATIONSLIST 321 FROM MUJAHEDDIN PUBLICATIONS MA Juiacst-- April -June, 19 88 Vol.1, No.4 AFGHAN JEHAD Editorial Q o c':. NC(° IN ME NAME OF GOD, MOST GRACICJUS, MOST MERCI.FU AFTER GENEVA Now that the Russian troops are on than way out from Afghanistan,' the focus on the Afghanistan issue is on two subjects; the nature of government in Kabul and finding a channel for the huge humanitarian assistance which the international community has indicated will provide to the war,ravaged Afghan- istan after the Soviet.