Inside Kenya's War on Terror: Breaking the Cycle of Violence in Garissa

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Al Shabaab's American Recruits

Al Shabaab’s American Recruits Updated: February, 2015 A wave of Americans traveling to Somalia to fight with Al Shabaab, an Al Qaeda-linked terrorist group, was described by the FBI as one of the "highest priorities in anti-terrorism." Americans began traveling to Somalia to join Al Shabaab in 2007, around the time the group stepped up its insurgency against Somalia's transitional government and its Ethiopian supporters, who have since withdrawn. At least 50 U.S. citizens and permanent residents are believed to have joined or attempted to join or aid the group since that time. The number of Americans joining Al Shabaab began to decline in 2012, and by 2014, the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria (ISIS) replaced Al Shabaab as the terrorist group of choice for U.S. recruits. However, there continue to be new cases of Americans attempting to join or aid Al Shabaab. These Americans have received weapons training alongside recruits from other countries, including Britain, Australia, Sweden and Canada, and have used the training to fight against Ethiopian forces, African Union troops and the internationally-supported Transitional Federal Government in Somalia, according to court documents. Most of the American men training with Al Shabaab are believed to have been radicalized in the U.S., especially in Minneapolis, according to U.S. officials. The FBI alleges that these young men have been recruited by Al Shabaab both on the Internet and in person. One such recruit from Minneapolis, 22-year-old Abidsalan Hussein Ali, was one of two suicide bombers who attacked African Union troops on October 29, 2011. -

Livestock Herd Structures and Dynamics in Garissa County, Kenya Patrick Mwambi Mwanyumba1*, Raphael Wahome Wahome2, Laban Macopiyo3 and Paul Kanyari4

Mwanyumba et al. Pastoralism: Research, Policy and Practice (2015) 5:26 DOI 10.1186/s13570-015-0045-6 SHORT REPORT Open Access Livestock herd structures and dynamics in Garissa County, Kenya Patrick Mwambi Mwanyumba1*, Raphael Wahome Wahome2, Laban MacOpiyo3 and Paul Kanyari4 Abstract In Kenya’s Northeastern Province, pastoralism is the main livestock production system and means of livelihood. However, pastoralists are facing increasing risks such as drought, insecurity, animal diseases, increasing human populations and land fragmentation. This study sought to evaluate household livestock herd structures and dynamics in view of such risks and subsistence and market demands. The study was conducted in Garissa County of Kenya, using a cross-sectional household survey. The data was analysed for descriptive statistics of household livestock status, dynamics and demographic parameters. The results showed that females of reproductive age formed over 50 % of all livestock species. Cattle had the highest turnover and all species’ mortalities accounted for the greater proportion of exits. Cattle had the highest multiplication and growth rates, but also the highest mortality, offtake, commercial offtake and intake rates. Goats had the lowest mortalities, offtake, commercial offtake and intake rates. Overall, the herds were structured to provide for both immediate and future needs in terms of milk, sales and herd replacement as well as for rapid recovery after disasters. The livestock herd dynamics indicate efforts at culling, restocking, retention of valuable categories of animals, and natural events. Livestock populations would be annihilated over time if the trends in end balances and negative growth rates were to continue and not be interrupted by the upward phases of the livestock cycles. -

Foreign Military Studies Office

community.apan.org/wg/tradoc-g2/fmso/ Foreign Military Studies Office Volume 8 Issue #5 OEWATCH May 2018 FOREIGN NEWS & PERSPECTIVES OF THE OPERATIONAL ENVIRONMENT CHINA’S REACH MIDDLE EAST, NORTH AFRICA LATIN AMERICA 3 Tension between Greece and Turkey in the Aegean Sea 24 Colombia and Brazil Look for Solutions to Deal with 44 China Holds Naval Review in the South China Sea 4 Disputes over Natural Gas Exploration in the Eastern Massive Venezuelan Migration 45 China’s Carrier Aviation Unit Improves Training Mediterranean 25 Brazil’s Federal Government Open Border Policy 46 Relocation in Southern Xinjiang: China Expands the Program 6 Iran and Russia Compete for Influence in Syria Challenges Frontier States 47 Perspectives on the Future of Marawi 8 “Turkey-Russia Rapprochement” Continues 26 Colombian-Venezuelan Border Ills 48 Indonesia Brings Terrorists and Victims Together 9 Turkish Defense Companies Reach Agreements with 27 Bolivarians Gain Influence over Colombian Resources 49 Thailand and Malaysia Build Border Wall Qatar’s Armed Forces 29 Venezuelan Elections Worth Anything? 10 A New Striking Power for the Turkish Armed Forces 30 Regarding the Colombian Elections 11 Will Iran Interfere in Kashmir? 31 Archbishop of Bogotá Confesses Left CAUCASUS, CENTRAL AND SOUTH ASIA 12 Rouhani Speaks about the Internet 31 Peruvian President Resigns, Replaced 50 India’s Red Line for China 13 Why Did the Mayor of Tehran Resign? 32 Brazilians Send Former President to Jail 51 The Future of Indian-Russian Security Cooperation 14 Former Governor: ISIS May -

Kenya Country Office

Kenya Country Office Flood Situation Report Report # 1: 24 November 2019 Highlights Situation in Numbers The National Disaster Operations Center (NDOC) estimates that at least 330,000 330,000 people are affected - 18,000 people have been displaced and 120 people affected people have died due to floods and landslides. (NDOC-24/11/2019) A total of 6,821 children have been reached through integrated outreach 31 services and 856 people have received cholera treatment through UNICEF-supported treatment centres. counties affected by flooding (NDOC-24/11/2019) A total of 270 households in Turkana County (out of 400 targeted) and 110 households in Wajir county have received UNICEF family emergency kits 120 (including 20-litre and 10-litre bucket), soap and water treatment tablets people killed from flooding through partnership with the Kenya Red Cross. (NDOC-24/11/2019) UNICEF has reached 55,000 people with WASH supplies consisting of 20- litre jerrycans, 10-litre buckets and multipurpose bar soap. 18,000 UNICEF has completed solarization of two boreholes reaching people displaced approximately 20,500 people with access to safe water in Garissa County. (NDOC-24/11/2019) Situation Overview & Humanitarian Needs Kenya has continued to experience enhanced rainfall resulting in flooding since mid-October, negatively impacting the lives and livelihoods of vulnerable populations. According to the National Disaster Operations Center (NDOC) 24 November 2019 updates, major roads have been cut off in 11 counties, affecting accessibility to affected populations for rapid assessments and delivery of humanitarian assistance, especially in parts of West Pokot, Marsabit, Mandera, Turkana, Garissa, Lamu, Mombasa, Tana River, Taita Taveta, Kwale and Wajir Counties. -

Somalia's Jubbaland: Past, Present and Potential Futures

Rift Valley Institute Meeting Report Nairobi Forum, 22 February 2013 POLITICS NOW Somalia's Jubbaland: Past, present and potential futures an ‘ethno-state’ liKe Puntland, because it is not Key points populated by a single clan. Some view Jubbaland as a § Due to its natural resources and location, Darod clan state, but when the large number of non- Jubbaland has the potential to be one of Darod populations along the Jubba river and in east Somalia’s richest regions, but conflict has bank communities taKen into account, the Darod clan kept it chronically unstable for over two probably comprise 50-60 per cent of the total decades. population. He warned that, if Jubbaland is treated as a Darod state and power-sharing is institutionalized § The regions of Jubbaland are not linked by along those lines, then other residents of the region road and have no history of shared would feel disenfranchised and could turn to al- administration. As an administrative unit, Shabaab. Jubbaland is not likely to be functional. Is Jubbaland viable as a federal state? First, for § The Somali constitution provides no clear Jubbaland to succeed as such a state, it needs some guidance on how newly declared federal history of shared governance and cooperation—and states are to be created, or what their it does not have such a history. Distant Jubbaland relations with the central government communities are very unlikely to respect claims of should be. authority from Kismayo. § The environmental consequences of the charcoal trade are having a negative impact A second criterion for judging whether a region could on livelihoods and food security. -

Baseline Review and Ecosystem Services Assessment of the Tana River Basin, Kenya

IWMI Working Paper Baseline Review and Ecosystem Services Assessment of the Tana 165 River Basin, Kenya Tracy Baker, Jeremiah Kiptala, Lydia Olaka, Naomi Oates, Asghar Hussain and Matthew McCartney Working Papers The publications in this series record the work and thinking of IWMI researchers, and knowledge that the Institute’s scientific management feels is worthy of documenting. This series will ensure that scientific data and other information gathered or prepared as a part of the research work of the Institute are recorded and referenced. Working Papers could include project reports, case studies, conference or workshop proceedings, discussion papers or reports on progress of research, country-specific research reports, monographs, etc. Working Papers may be copublished, by IWMI and partner organizations. Although most of the reports are published by IWMI staff and their collaborators, we welcome contributions from others. Each report is reviewed internally by IWMI staff. The reports are published and distributed both in hard copy and electronically (www.iwmi.org) and where possible all data and analyses will be available as separate downloadable files. Reports may be copied freely and cited with due acknowledgment. About IWMI IWMI’s mission is to provide evidence-based solutions to sustainably manage water and land resources for food security, people’s livelihoods and the environment. IWMI works in partnership with governments, civil society and the private sector to develop scalable agricultural water management solutions that have -

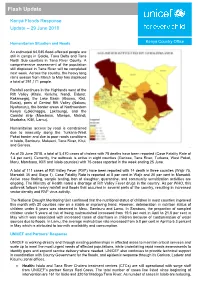

Flash Update

Flash Update Kenya Floods Response Update – 29 June 2018 Humanitarian Situation and Needs Kenya Country Office An estimated 64,045 flood-affected people are still in camps in Galole, Tana Delta and Tana North Sub counties in Tana River County. A comprehensive assessment of the population still displaced in Tana River will be completed next week. Across the country, the heavy long rains season from March to May has displaced a total of 291,171 people. Rainfall continues in the Highlands west of the Rift Valley (Kitale, Kericho, Nandi, Eldoret, Kakamega), the Lake Basin (Kisumu, Kisii, Busia), parts of Central Rift Valley (Nakuru, Nyahururu), the border areas of Northwestern Kenya (Lokichoggio, Lokitaung), and the Coastal strip (Mombasa, Mtwapa, Malindi, Msabaha, Kilifi, Lamu). Humanitarian access by road is constrained due to insecurity along the Turkana-West Pokot border and due to poor roads conditions in Isiolo, Samburu, Makueni, Tana River, Kitui, and Garissa. As of 25 June 2018, a total of 5,470 cases of cholera with 78 deaths have been reported (Case Fatality Rate of 1.4 per cent). Currently, the outbreak is active in eight counties (Garissa, Tana River, Turkana, West Pokot, Meru, Mombasa, Kilifi and Isiolo counties) with 75 cases reported in the week ending 25 June. A total of 111 cases of Rift Valley Fever (RVF) have been reported with 14 death in three counties (Wajir 75, Marsabit 35 and Siaya 1). Case Fatality Rate is reported at 8 per cent in Wajir and 20 per cent in Marsabit. Active case finding, sample testing, ban of slaughter, quarantine, and community sensitization activities are ongoing. -

Mini-SITREP XXXIV

mini-SITREP XXXIV Eldoret Agricultural Show - February 1959. HM The Queen Mother inspecting Guard of Honour provided by ‘C’ Company commanded by Maj Jock Rutherford [KR5659]. Carrying the Queen Mother’s Colour Lt Don Rooken- Smith [KR5836]. Third from right wearing the Colorado Beetle, Richard Pembridge [KR6381] Edited and Printed by the Kenya Regiment Association (KwaZulu-Natal) – June 2009 1 KRA/EAST AFRICA SCHOOLS DIARY OF EVENTS: 2009 KRA (Australia) Sunshine Coast Curry Lunch, Oxley Golf Club Sun 16th Aug (TBC) Contact: Giles Shaw. 07-3800 6619 <[email protected]> Sydney’s Gold Coast. Ted Downer. 02-9769 1236 <[email protected]> Sat 28th Nov (TBC) East Africa Schools - Australia 10th Annual Picnic. Lane Cove River National Park, Sydney Sun 25th Oct Contact: Dave Lichtenstein 01-9427 1220 <[email protected]> KRAEA Remembrance Sunday and Curry Lunch at Nairobi Clubhouse Sun 8th Nov Contact: Dennis Leete <[email protected]> KRAENA - England Curry Lunch: St Cross Cricket Ground, Winchester Thu 2nd Jul AGM and Lunch: The Rifles London Club, Davies St Wed 18th Nov Contact: John Davis. 01628-486832 <[email protected]> SOUTH AFRICA Cape Town: KRA Lunch at Mowbray Golf Course. 12h30 for 13h00 Thu 18th Jun Contact: Jock Boyd. Tel: 021-794 6823 <[email protected]> Johannesburg: KRA Lunch Sun 25th Oct Contact: Keith Elliot. Tel: 011-802 6054 <[email protected]> KwaZulu-Natal: KRA Saturday quarterly lunches: Hilton Hotel - 13 Jun, 12 Sep and 12 Dec Contact: Anne/Pete Smith. Tel: 033-330 7614 <[email protected]> or Jenny/Bruce Rooken-Smith. Tel: 033-330 4012 <[email protected]> East Africa Schools’ Lunch. -

National Drought Early Warning Bulletin June 2021

NATIONAL DROUGHT MANAGEMENT AUTHORITY National Drought Early Warning Bulletin June 2021 1 Drought indicators Rainfall Performance The month of May 2021 marks the cessation of the Long- Rains over most parts of the country except for the western and Coastal regions according to Kenya Metrological Department. During the month of May 2021, most ASAL counties received over 70 percent of average rainfall except Wajir, Garissa, Kilifi, Lamu, Kwale, Taita Taveta and Tana River that received between 25-50 percent of average amounts of rainfall during the month of May as shown in Figure 1. Spatio-temporal rainfall distribution was generally uneven and poor across the ASAL counties. Figure 1 indicates rainfall performance during the month of May as Figure 1.May Rainfall Performance percentage of long term mean(LTM). Rainfall Forecast According to Kenya Metrological Department (KMD), several parts of the country will be generally dry and sunny during the month of June 2021. Counties in Northwestern Region including Turkana, West Pokot and Samburu are likely to be sunny and dry with occasional rainfall expected from the third week of the month. The expected total rainfall is likely to be near the long-term average amounts for June. Counties in the Coastal strip including Tana River, Kilifi, Lamu and Kwale will likely receive occasional rainfall that is expected throughout the month. The expected total rainfall is likely to be below the long-term average amounts for June. The Highlands East of the Rift Valley counties including Nyeri, Meru, Embu and Tharaka Nithi are expected to experience occasional cool and cloudy Figure 2.Rainfall forecast (overcast skies) conditions with occasional light morning rains/drizzles. -

Countering Terrorism in East Africa: the U.S

Countering Terrorism in East Africa: The U.S. Response Lauren Ploch Analyst in African Affairs November 3, 2010 Congressional Research Service 7-5700 www.crs.gov R41473 CRS Report for Congress Prepared for Members and Committees of Congress Countering Terrorism in East Africa: The U.S. Response Summary The United States government has implemented a range of programs to counter violent extremist threats in East Africa in response to Al Qaeda’s bombing of the U.S. embassies in Tanzania and Kenya in 1998 and subsequent transnational terrorist activity in the region. These programs include regional and bilateral efforts, both military and civilian. The programs seek to build regional intelligence, military, law enforcement, and judicial capacities; strengthen aviation, port, and border security; stem the flow of terrorist financing; and counter the spread of extremist ideologies. Current U.S.-led regional counterterrorism efforts include the State Department’s East Africa Regional Strategic Initiative (EARSI) and the U.S. military’s Combined Joint Task Force – Horn of Africa (CJTF-HOA), part of U.S. Africa Command (AFRICOM). The United States has also provided significant assistance in support of the African Union’s (AU) peace operations in Somalia, where the country’s nascent security forces and AU peacekeepers face a complex insurgency waged by, among others, Al Shabaab, a local group linked to Al Qaeda that often resorts to terrorist tactics. The State Department reports that both Al Qaeda and Al Shabaab pose serious terrorist threats to the United States and U.S. interests in the region. Evidence of linkages between Al Shabaab and Al Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula, across the Gulf of Aden in Yemen, highlight another regional dimension of the threat posed by violent extremists in the area. -

Mandera County Hiv and Aids Strategic Plan 2016-2019

MANDERA COUNTY HIV AND AIDS STRATEGIC PLAN 2016-2019 “A healthy and productive population” i MANDERA COUNTY HIV AND AIDS STRATEGIC PLAN 2016-2019 “A healthy and productive population” Any part of this document may be freely reviewed, quoted, reproduced or translated in full or in part, provided the source is acknowledged. It may not be sold or used for commercial purposes or for profit. iv MANDERA COUNTY HIV & AIDS STRATEGIC PLAN (2016- 2019) Table of Contents Acronyms and Abbreviations vii Foreword viii Preface ix Acknowledgement x CHAPTER ONE: INTRODUCTION 1.1 Background Information xii 1.2 Demographic characteristics 2 1.3 Land availability and use 2 1.3 Purpose of the HIV Plan 1.4 Process of developing the HIV and AIDS Strategic Plan 1.5 Guiding principles CHAPTER TWO: HIV STATUS IN THE COUNTY 2.1 County HIV Profiles 5 2.2 Priority population 6 2.3 Gaps and challenges analysis 6 CHAPTER THREE: PURPOSE OF Mcasp, strateGIC PLAN DEVELOPMENT process AND THE GUIDING PRINCIPLES 8 3.1 Purpose of the HIV Plan 9 3.2 Process of developing the HIV and AIDS Strategic Plan 9 3.3 Guiding principles 9 CHAPTER FOUR: VISION, GOALS, OBJECTIVES AND STRATEGIC DIRECTIONS 10 4.1 The vision, goals and objectives of the county 11 4.2 Strategic directions 12 4.2.1 Strategic direction 1: Reducing new HIV infection 12 4.2.2 Strategic direction 2: Improving health outcomes and wellness of people living with HIV and AIDS 14 4.2.3 Strategic Direction 3: Using human rights based approach1 to facilitate access to services 16 4.2.4 Strategic direction 4: Strengthening Integration of community and health systems 18 4.2.5 Strategic Direction 5: Strengthen Research innovation and information management to meet the Mandera County HIV Strategy goals. -

Disaster, Terror, War, and Chemical, Biological, Radiological, Nuclear, and Explosive (CBRNE) Events

Disaster, Terror, War, and Chemical, Biological, Radiological, Nuclear, and Explosive (CBRNE) Events Date Location Agent Notes Source 28 Apr Kano, Nigeria VBIED Five soldiers were killed and 40 wounded when a Boko http://www.dailystar.com.lb/News/World/2017/ 2017 Haram militant drove his VBIED into a convoy. Apr-28/403711-suicide-bomber-kills-five-troops- in-ne-nigeria-sources.ashx 25 Apr Pakistan Land mine A passenger van travelling within Parachinar hit a https://www.dawn.com/news/1329140/14- 2017 landmine, killing fourteen and wounding nine. killed-as-landmine-blast-hits-van-carrying- census-workers-in-kurram 24 Apr Sukma, India Small arms Maoist rebels ambushed CRPF forces and killed 25, http://odishasuntimes.com/2017/04/24/12-crpf- 2017 wounding six or so. troopers-killed-in-maoist-attack/ 15 Apr Aleppo, Syria VBIED 126 or more people were killed and an unknown https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/2017_Aleppo_suici 2017 number wounded in ISIS attacks against a convoy of de_car_bombing buses carrying refugees. 10 Apr Somalia Suicide Two al-Shabaab suicide bombs detonated in and near http://www.reuters.com/article/us-somalia- 2017 bombings Mogadishu killed nine soldiers and a civil servant. security-blast-idUSKBN17C0JV?il=0 10 Apr Wau, South Ethnic violence At least sixteen people were killed and ten wounded in http://www.reuters.com/article/us-southsudan- 2017 Sudan ethnic violence in a town in South Sudan. violence-idUSKBN17C0SO?il=0 10 Apr Kirkuk, Iraq Small arms Twelve ISIS prisoners were killed by a firing squad, for http://www.iraqinews.com/iraq-war/islamic- 2017 reasons unknown.