Studying the Phonology of the Olùkùmi, Igala, Owé and Yorùba Languages: a Comparative Analysis1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Informal Microfinance and Economic Activities of Rural Dwellers in Kwara South Senatorial District of Nigeria

International Journal of Business and Social Science Vol. 2 No. 15; August 2011 INFORMAL MICROFINANCE AND ECONOMIC ACTIVITIES OF RURAL DWELLERS IN KWARA SOUTH SENATORIAL DISTRICT OF NIGERIA IJAIYA, Muftau Adeniyi Department of Accounting and Finance University of Ilorin, Ilorin, Nigeria E-mail : [email protected], Phone: +2348036973561 Abstract Rural areas, like urban areas have increasing demand for credit because such credit reduces the impact of seasonality on incomes. However, formal financial institutions have maintained low presence in the rural areas. This has affected the rural dwellers’ access to deposit savings and credits that can improve their economic activities. This study examined the influence of informal microfinance on economic activities of rural dwellers in the selected rural areas of Kwara South Senatorial District. Using a multiple regression analysis, six hundred (600) questionnaire was administered on members of informal microfinance institution in the study area, the study found that fund provided as credit facilities for transaction purposes, funds for housing and combating diseases have significant influence on the economic activities of the rural areas. The study recommends group savings and group lending in order to increase savings and credits to the rural dwellers. Government should also provide improved infrastructural facilities that would enable rural dwellers have more access to their economic activities Key Words: Microfinance, Informal, Economic Activities, Rural, Kwara 1.0 Introduction Africa‟s development challenges go deeper than low income, falling trade shares, low savings and slow growth. They also include inequality and uneven access to productive resources, social exclusion and insecurity especially among the women (Pitamber, 2003). However, more specific concern is raised in Nigeria due to rural-urban disparities in income distribution, access to education and health care services, and prevalence of ethnic or cross-boundary conflicts. -

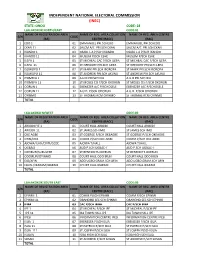

Ondo Code: 28 Lga:Akokok North/East Code:01 Name of Registration Area Name of Reg

INDEPENDENT NATIONAL ELECTORAL COMMISSION (INEC) STATE: ONDO CODE: 28 LGA:AKOKOK NORTH/EAST CODE:01 NAME OF REGISTRATION AREA NAME OF REG. AREA COLLATION NAME OF REG. AREA CENTRE S/N CODE (RA) CENTRE (RACC) (RAC) 1 EDO 1 01 EMMANUEL PRI.SCHEDO EMMANUEL PRI.SCHEDO 2 EKAN 11 02 SALEM A/C PRI.SCH EKAN SALEM A/C PRI.SCH EKAN 3 IKANDO 1 03 OSABL L.A P/SCH IKANDO OSABL L.A P/SCH IKANDO 4 IKANDO 11 04 MUSLIM P/SCH ESHE MUSLIM P/SCH ESHE 5 ILEPA 1 05 ST MICHEAL CAC P/SCH ILEPA ST MICHEAL CAC P/SCH ILEPA 6 ILEPA 11 06 ST GREGORY PRI.SCH ILEPA ST GREGORY PRI.SCH ILEPA 7 ISOWOPO 1 07 ST MARK PRI.SCH IBOROPA ST MARK PRI.SCH IBOROPA 8 ISOWOPO 11 08 ST ANDREW PRI.SCH AKUNU ST ANDREW PRI.SCH AKUNU 9 IYOMEFA 1 09 A.U.D PRI.SCH IKU A.U.D PRI.SCH IKU 10 IYOMEFA 11 10 ST MOSES CIS P/SCH OKORUN ST MOSES CIS P/SCH OKORUN 11 OORUN 1 11 EBENEZER A/C P/SCHOSELE EBENEZER A/C P/SCHOSELE 12 OORUN 11 12 A.U.D. P/SCH ODORUN A.U.D. P/SCH ODORUN 13 OYINMO 13 ST THOMAS RCM OYINMO ST THOMAS RCM OYINMO TOTAL LGA:AKOKO N/WEST CODE:02 NAME OF REGISTRATION AREA NAME OF REG. AREA COLLATION NAME OF REG. AREA CENTRE S/N CODE (RA) CENTRE (RACC) (RAC) 1 ARIGIDI IYE 1 01 COURT HALL ARIGIDI COURT HALL ARIGIDI 2 ARIGIDI 11 02 ST JAMES SCH IMO ST JAMES SCH IMO 3 OKE AGBE 03 ST GOERGE P/SCH OKEAGBE ST GOERGE P/SCH OKEAGBE 4 OYIN/OGE 04 COMM.P/SCH OKE AGBE COMM.P/SCH OKE AGBE 5 AJOWA/ILASI/ERITI/GEDE 05 AJOWA T/HALL AJOWA T/HALL 6 OGBAGI 06 AUD P.SCH OGBAC-I AUD P.SCH OGBAC-I 7 OKEIRUN/SURULERE 07 ST BENEDICTS OKERUN ST BENEDICTS OKERUN 8 ODOIRUN/OYINMO 08 COURT HALL ODO IRUN COURT HALL ODO IRUN 9 ESE/AFIN 09 ADO UGBO GRAM.SCH AFIN ADO UGBO GRAM.SCH AFIN 10 EBUSU/IKARAM/IBARAM 10 COURT HALL IKARAM COURT HALL IKARAM TOTAL LGA:AKOKOK SOUTH EAST CODE:03 NAME OF REGISTRATION AREA NAME OF REG. -

Urban Sprawl, Pattern and Measurement in Lokoja, Nigeria

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Research Papers in Economics Alabi M. O. URBAN SPRAWL, PATTERN AND MEASUREMENT IN LOKOJA, NIGERIA URBAN SPRAWL, PATTERN AND MEASUREMENT IN LOKOJA, NIGERIA Michael Oloyede ALABI Department of Geography and Planning, Kogi State University P.M. B. 1008, Anyigba, Nigeria ement [email protected] Abstract Lokoja have been experiencing a large influx of population from its surrounding regions, which had led to rapid growth and expansion that had left profound changes on the landscape in terms of land use and land cover. This study uses the GIS techniques and the application of Shannon’s entropy theory to measure the behavior of sprawl which is based on the notion that landscape entropy or disorganization increases with sprawl, analysis was carried out based on the integration of remote sensing and GIS, the measurement of entropy is devised based on the town location factors, distance from roads, to reveal and capture spatial patterns of urban sprawl. Then Entropy value for each zone revealed a high value, especially areas outside the core city area; like Felele, with the entropy of 0.3, Adankolo, 0.2 and Lokongoma, 0.2. These areas are evenly dispersed settlement, as one move away from the city core. Study shows a correlation of population densities and entropy values of 1987 and 2007, for areas like Felele ,Adankolo, and Lokongoma , which is indicative of spread over space , an evidence of sprawl. But as we go down the table the entropy values seem to tend towards zero. -

Isbn: 978-978-57350-2-4

ASSESSMENT AND REPAIR OF SOLAR STREETLIGHTS IN TOWNSHIP AND RURAL COMMUNITIES (Kwara, Kogi, Osun, Oyo, Nassarawa and Ekiti States) A. S. OLADEJI B. F. SULE A. BALOGUN I. T. ADEDAYO B. N. LAWAL TECHNICAL REPORT NO. 11 ISBN: 978-978-57350-2-4 NATIONAL CENTRE FOR HYDROPOWER RESEARCH AND DEVELOPMENT ENERGY COMMISSION OF NIGERIA UNIVERSITY OF ILORIN, ILORIN, NIGERIA DECEMBER, 2013 i TABLE OF CONTENTS Table of Contents ii List of Figures iii List of Table iii 1.0 Introduction 2 1.1Background 2 1.2Objectives 4 2. 0Assessment of ECN 2008/2009 Rural Solar Streetlight Projects 5 2.1 Results of 2012 Re-assessment Exercise 5 2.1.1 Nasarawa State 5 2.1.1.1 Keffi 5 2.1.2 Kogi State 5 2.1.2.1 Banda 5 2.1.2.2 Kotonkarfi 5 2.1.2.3 Anyigba 5 2.1.2.4 Dekina 6 2.1.2.5 Egume 6 2.1.2.6 Acharu/Ogbogodo/Itama/Elubi 6 2.1.2.7 Abejukolo-Ife/Iyale/Oganenigu 6 2.1.2.8 Inye/Ofuigo/Enabo 6 2.1.2.9 Ankpa 6 2.1.2.10 Okenne 7 2.1.2.11 Ogaminana/Ihima 7 2.1.2.12 Kabba 7 2.1.2.13 Isanlu/Egbe 7 2.1.2.14 Okpatala-Ife / Dirisu / Obakume 7 2.1.2.15 Okpo / Imane 7 2.1.2.16 Gboloko / Odugbo / Mazum 8 2.1.2.17 Onyedega / Unale / Odeke 8 2.1.2.18 Ugwalawo /FGC / Umomi 8 2.1.2.19 Anpaya 8 2.1.2.20 Baugi 8 2.1.2.21 Mabenyi-Imane 9 ii 2.1.3 Oyo State 9 2.1.3.1 Gambari 9 2.1.3.2 Ajase 9 2.1.4 Kwara State 9 2.1.4.1Alaropo 9 2.1.5 Ekiti State 9 2.1.5.1 Iludun-Ekiti 9 2.1.5.2 Emure-Ekiti 9 2.1.5.3 Imesi-Ekiti 10 2.1.6 Osun State 10 2.1.6.1 Ile-Ife 10 2.1.6.3 Oke Obada 10 2.1.6.4 Ijebu-Jesa / Ere-Jesa 11 2.2 Summary Report of 2012 Re-Assessment Exercise, Recommendations and Cost for the Repair 11 2.3 Results of 2013 Re-assessment Exercise 27 2.2.1 Results of the Re-assessment Exercise 27 2.3.1.1 Results of Reassessment Exercise at Emir‟s Palace Ilorin, Kwara State 27 2.3.1.2 Results of Re-assessment Exercise at Gambari, Ogbomoso 28 2.3.1.3 Results of Re-assessment Exercise at Inisha 1&2, Osun State 30 3.0 Repairs Works 32 3.1 Introduction 32 3.2 Gambari, Surulere, Local Government, Ogbomoso 33 3.3 Inisha 2, Osun State 34 4. -

Mannitol Dosing Error During Pre-Neurosurgical Care of Head Injury: a Neurosurgical In-Hospital Survey from Ibadan, Nigeria

Published online: 2021-01-29 THIEME Original Article 171 Mannitol Dosing Error during Pre-neurosurgical Care of Head Injury: A Neurosurgical In-Hospital Survey from Ibadan, Nigeria Amos Olufemi Adeleye1,2 Toyin Ayofe Oyemolade2 Toluyemi Adefolarin Malomo2 Oghenekevwe Efe Okere2 1Department of Surgery, Division of Neurological Surgery, College Address for correspondence Amos Olufemi Adeleye, MBBS, of Medicine, University of Ibadan, Ibadan, Nigeria Department of Neurological Surgery, University College Hospital, 2Department of Neurological Surgery, University College Hospital, UCH, Ibadan, Owo, PMB 1053, Nigeria Ibadan, Nigeria (e-mail: [email protected]). J Neurosci Rural Pract:2021;12:171–176 Abstract Objectives Inappropriate use of mannitol is a medical error seen frequently in pre-neurosurgical head injury (HI) care that may result in serious adverse effects. This study explored this medical error amongst HI patients in a Nigerian neurosurgery unit. Methods We performed a cross-sectional analysis of a prospective cohort of HI patients who were administered mannitol by their initial non-neurosurgical health care givers before referral to our center over a 22-month period. Statistical Analysis A statistical software was used for the analysis with which an α value of <0.05 was deemed clinically significant. Results Seventy-one patients were recruited: 17 (23.9%) from private hospitals, 13 (18.3%) from primary health facilities (PHFs), 20 (28.2%) from secondary health facilities (SHFs), and 21 (29.6%) from tertiary health facilities (THFs). Thirteen patients (18.3%) had mild HI; 29 (40.8%) each had moderate and severe HI, respectively. Pupillary abnormalities were documented in five patients (7.04%) with severe HI and neurological deterioration in two with mild HI. -

Igala People

Igala people The Brazilian-designed Volkswagen Brasilia was sold in Nigeria as the Igala. The name of the car was derived from the Yoruba word for antelope "ìgalà" and has no connection with the Igala ethnic group. Igala are an ethnic group of Nigeria. Igala practice a number of different religions, including animism, Christianity, and Islam. The home of the Igala people is situated east of the river Niger and Benue confluence and astride the Niger in Lokoja, Kogi state of Nigeria. The area is approximately between latitude 6°30 and 8°40 north and longitude 6°30 and 7°40 east and covers an area of about 13,665 square kilometers (Oguagha P.A 1981) The Igala population is estimated at two million, they can also be found in Delta, Anambra and Edo States of Nigeria. The Igala language is closely related to the Yoruba and Itsekiri languages. In Igala tradition, infants from some parts of the kingdom, like Ankpa receive three deep horizontal cuts on each side of the face, slightly above the corners of their mouths, as a way of identifying each other. However, this practice is becoming less common. The Igalas are ruled by a father figure called the Attah. The word Attah means 'Father' and the full title of the ruler is 'Attah Igala', meaning, the Father of Igalas (the Igala word for King is Onu). Among the most revered Attahs of the Igala kingdom are Attah Ayegba Oma Idoko and Atta Ameh Oboni. According to oral tradition, Attah Ayegba Oma Idoko offered his most beloved daughter, Inikpi to ensure that the Igalas win a war of liberation from the Jukuns' dominance. -

World Bank Document

The Final Draft RAP Report for Agassa Gully Erosion Sites for NEWMAP, Kogi State. Public Disclosure Authorized FINAL REPORT RESETTLEMENT ACTION PLAN (RAP) FOR AGASSA EROSION SITE, OKENE LOCAL GOVERNMENT AREA Public Disclosure Authorized SUBMITTED TO Public Disclosure Authorized KOGI STATE NIGERIA EROSION AND WATERSHED MANAGEMENT PROJECT (KGS-NEWMAP) PLOT 247, TUNDE OGBEHA STREET, GRA, LOKOJA. Public Disclosure Authorized i The Final Draft RAP Report for Agassa Gully Erosion Sites for NEWMAP, Kogi State. RAP Basic Data/Information S/N Subject Data 1 Intervention Site Agassa Gully Erosion sub-project, Okene LGA, Kogi State 2 Need for RAP Resettlement of People Displaced by the Project/Work 3 Nature of Civil Works Stabilization or rehabilitation in and around Erosion Gully site - stone revetment to reclaim and protect road way and reinforcement of exposed soil surface to stop scouring action of flow velocity, extension of culvert structure from the Agassa Road into the gully, chute channel, stilling basin, apron and installation of rip-rap and gabions mattress at some areas. Zone of Impact 5m offset from the gully edge. 4 Benefit(s) of the Intervention Improved erosion management and gully rehabilitation with reduced loss of infrastructure including roads, houses, agricultural land and productivity, reduced siltation in rivers leading to less flooding, and the preservation of the water systems for improved access to domestic water supply. 5 Negative Impact and No. of PAPs A census to identify those that could be potentially affected and eligible for assistance has been carried out. However, Based on inventory, a total of 241 PAPs have been identified. -

Oja Representational Objects in Yewaland, Ogun State, Nigeria Ayedun Matthew Kolawole Ab

African Scholar VOL. 18 NO. 6 Publications & ISSN: 2110-2086 Research SEPTEMBER, 2020 International African Scholar Journal of Humanities and Social Sciences (JHSS-6) Study of Forms and Functions of Esu – Oja Representational Objects in Yewaland, Ogun State, Nigeria Ayedun Matthew Kolawole Fine and Applied Arts Department, School of Vocational and Technical Education, Tai Solarin College of Education, Omu – Ijebu Abstract The representational images such as pots, rattles, bracelets, stones, cutlasses, wooden combs, staffs, mortals, brooms, etc. are religious and its significance for the worshippers were that they had faith in it. The denominator in the worship of all gods and spirits everywhere is faith. The power of an image was believed to be more real than that of a living being. The Yoruba appear to be satisfied with the gods with whom they are in immediate touch because they believe that when the Orisa have been worshipped, they will transmit what is necessary to Olodumare. This paper examines the traditional practices of the people of Yewa and discovers why Esu is market appellate. It focuses on the classifications of the forms and functions of Esu-Oja representational objects in selected towns in Yewaland. Keywords: appellate, classifications, divinities, fragment, forms, images, libations, mystical powers, Olodumare, representational, sacred, sacrifices, shrine, spirit archetype, transmission and transformation. Introduction Yewa which was formally called there are issues of intra-regional “Egbado” is located on Nigeria’s border conflicts that call for urgent attention. with the Republic of Benin. Yewa claim The popular decision to change the common origin from Ile-Ife, Oyo, ketu, Egbado name according to Asiwaju and Benin. -

KOGI STATE GOVERNORSHIP ELECTION 2019 Brief

KOGI STATE GOVERNORSHIP ELECTION 2019 Brief 1 BACKGROUND The Kogi State Governorship election is scheduled to take place on Saturday, November 16, 2019. The election will be taking place simultaneously with the governorship elections in Bayelsa State. These governorship elections would be the first elections to be conducted by INEC post-2019 general elections. Kogi State, with a land area of 29,833 square kilometres, was carved out of Kwara and Benue states on August 27, 1991. Kogi is one of the states in the north-central zone of Nigeria. It is popularly called the confluence state due to the fact that the confluence of Rivers Niger and Benue occur there. There are three main ethnic groups in the state namely Igala, Ebira, and Okun; with the Igalas being the largest ethnic group. Lokoja is the state capital. Kogi State, with a population of 3,314,043 according to 2006 census, is the most centrally located of all the states of the federation. It shares common boundaries with Niger, Kwara and Nasarawa states as well as the Federal Capital Territory (FCT) to the north Benue and Enugu states to the East; Enugu and Anambra states to the south; and to the west by Ondo, Ekiti and Edo states. PRESENT DAY GOVERNMENT OF KOGI STATE The present Governor of Kogi is Alhaji Yahaya Bello and the Deputy Governor of the State is Edward Onoja (his former Chief of Staff), who was sworn into office in October 2019 fpllpowing the controversial impeachment of the former Deputy Governor, Simon Achuba. On 5th December 2015, Governor Yahaya Bello was declared the elected Governor of the State after a supplementary election was held to conclude the inconclusive election of Saturday, 22nd November 2015. -

English Fricative Rendition of Educated Speakers of English from a North-Central City of Nigeria

International Journal of Language and Literary Studies Volume 2, Issue 3, 2020 Homepage : http://ijlls.org/index.php/ijlls English Fricative Rendition of Educated Speakers of English from a North-Central City of Nigeria Theodore Shey Nsairun Obafemi Awolowo University, Ile – Ife, Nigeria/Federal University Lokoja, Nigeria [email protected] Eunice Fajobi *(Correspondence Author) [email protected] Obafemi Awolowo University, Ile – Ife, Nigeria DOI: http://doi.org/10.36892/ijlls.v2i3.321 Received: Abstract 22/05/2020 This paper examines the influence of ethnicity on the realization of the Accepted: English fricatives articulated by selected educated speakers of English 13/08/2020 from four ethnic groups of Ebira, Igala, Hausa and Okun-Yoruba residing in Lokoja, a North-Central city of Nigeria. Data for the study consist of 1080 tokens elicited from 120 informants. The study was Keywords: English fricatives, guided by a synthesis of the theoretical frameworks of Honey’s (1997) ethnicity, Sociophonology and Azevedo’s (1981) Contrastive Phonology. sociophonology, Perceptual and acoustic analyses of the data reveal that, although contrastive phonology, speakers tend to not articulate sounds that are absent in their phonemic acoustic analysis inventory with the dexterity expected of their level of education, co- habitation seems a factor that has robbed off on the respondents’ level of performance in this study. Results reveal further that 80% overcame their linguistic challenges to correctly articulate the test items while 30% generally had difficulty articulating the interdental fricatives /P/ and /D/ and the voiced palato-alveolar fricative /Z/; perhaps, because these sounds are absent in their respective phonemic inventories. -

Trends in Owo Traditional Sculptures: 1995 – 2010

Mgbakoigba, Journal of African Studies. Vol.5 No.1. December 2015 TRENDS IN OWO TRADITIONAL SCULPTURES: 1995 – 2010 Ebenezer Ayodeji Aseniserare Department of Fine and Applied Arts University of Benin, Benin City [email protected] 08034734927, 08057784545 and Efemena I. Ononeme Department of Fine and Applied Arts University of Benin, Benin City [email protected] [email protected] 08023112353 Abstract This study probes into the origin, style and patronage of the traditional sculptures in Owo kingdom between 1950 and 2010. It examines comparatively the sculpture of the people and its affinity with Benin and Ife before and during the period in question with a view to predicting the future of the sculptural arts of the people in the next few decades. Investigations of the study rely mainly on both oral and written history, observation, interviews and photographic recordings of visuals, visitations to traditional houses and Owo museum, oral interview of some artists and traditionalists among others. Oral data were also employed through unstructured interviews which bothered on analysis, morphology, formalism, elements and features of the forms, techniques and styles of Owo traditional sculptures, their resemblances and relationship with Benin and Ife artefacts which were traced back to the reigns of both Olowo Ojugbelu 1019 AD to Olowo Oshogboye, the Olowo of Owo between 1600 – 1684 AD, who as a prince, lived and was brought up by the Oba of Benin. He cleverly adopted some of Benin‟s sculptural and historical culture and artefacts including carvings, bronze work, metal work, regalia, bead work, drums and some craftsmen with him on his return to Owo to reign. -

Multilingualism and the Ethnic Identity of the Ette People

Mgbakoigba: Journal of African Studies, Volume 4, 2015. MULTILINGUALISM AND THE ETHNIC IDENTITY OF THE ETTE PEOPLE Martha Chidimma Egenti Department of Linguistics Nnamdi Azikiwe University Awka [email protected] Abstract Due to their diverse nature, the classification of indigenous languages in Nigeria ranks some of them as major, main and small group languages. The Ette people speak two main, and one major, Nigerian languages namely: Idoma, Igala and Igbo respectively. This paper sets out to examine the Ette people in the light of their ethnic identity and also to ascertain which of the languages spoken has the highest percentage with regard to its status and level of proficiency. Primary data were collected from native speakers of Ette resident in Igboeze North Local Government Area of Enugu State using Phinney’s (1999) Ethnic Identity measure questionnaire. The findings show that the Idoma language has the highest percentage with regard to language proficiency and use, followed by Igala and then Igbo which is also spoken in Ette perhaps because it shares border with Enugu and Kogi States. The paper in discussing the relationship of language and identity observes that language does not mark the ethnic identity of the Ette people because of their multilingual nature. Also, the geographical location which situates them in other ethnic groups does not give them a sense of belonging. This has resulted to different forms of agitations. Introduction Nigeria is made up of diverse indigenous languages which rank them as major, main and small group languages (Bamgbose 1991:4). Ejele (2007:160) states that languages that are formerly called minority language are now made up of „main‟ languages and „small group‟ languages.