Articles Safety and Efficacy of Testosterone for Women

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Comparison of the Effects of High Dose Testosterone and 19-Nortestosterone to a Replacement Dose of Testosterone on Strength and Body Composition in Normal Men

J. Steroid Biochem. Molec. Biol. Vol. 40, No. 4-6, pp. 607~12, 1991 0960-0760/91 $3.00 + 0.00 Printed in Great Britain Pergamon Press plc COMPARISON OF THE EFFECTS OF HIGH DOSE TESTOSTERONE AND 19-NORTESTOSTERONE TO A REPLACEMENT DOSE OF TESTOSTERONE ON STRENGTH AND BODY COMPOSITION IN NORMAL MEN KARL E. FRIEDL,* JOSEPH R. DETTORI, CHARLES J. HANNAN JR, TROY H. PATIENCE and STEPHENR. PLYMATE Exercise Physiology Division, U.S. Army Research Institute of Environmental Medicine, Natick, MA and Department of Clinical Investigation, Madigan Army Medical Center, Tacoma, WA, U.S.A. Summary--We examined the extent to which supraphysiological doses of androgen can modify body composition and strength in normally virilized men. In doubly blind tests, 30 healthy young men received testosterone enanthate (TE) or 19-nortestosterone decanoate (ND), at 100mg/wk or 300mg/wk for 6 weeks. The TE-100mg/wk group served as replacement dose comparison, maintaining pretreatment serum testosterone levels, while keeping all subjects blinded to treatment, particularly through reduction in testicular volumes. Isokinetic strength measurements were made for the biceps brachii and quadriceps femoris muscle groups before treatment and 2-3 days after the 6th injection. Small improvements were noted in all groups but the changes were highly variable; a trend to greater and more consistent strength gain occurred in the TE-300mg/wk group. There was no change in weight for TE-100 mg/wk but an average gain of 3 kg in each of the other groups. No changes in 4 skinfold thicknesses or in estimated percent body fat were observed. -

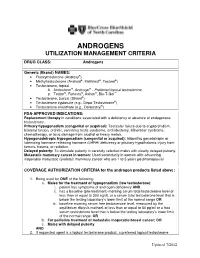

Androgens Utilization Management Criteria

ANDROGENS UTILIZATION MANAGEMENT CRITERIA DRUG CLASS: Androgens Generic (Brand) NAMES: • Fluoxymesterone (Androxy®) • Methyltestosterone (Android®, Methitest®, Testred®) • Testosterone, topical A. Androderm®, Androgel® - Preferred topical testosterone ® ® ® ™ B. Testim , Fortesta , Axiron , Bio-T-Gel • Testosterone, buccal (Striant®) • Testosterone cypionate (e.g., Depo-Testosterone®) • Testosterone enanthate (e.g., Delatestryl®) FDA-APPROVED INDICATIONS: Replacement therapy in conditions associated with a deficiency or absence of endogenous testosterone. Primary hypogonadism (congenital or acquired): Testicular failure due to cryptorchidism, bilateral torsion, orchitis, vanishing testis syndrome, orchidectomy, Klinefelter syndrome, chemotherapy, or toxic damage from alcohol or heavy metals. Hypogonadotropic hypogonadism (congenital or acquired): Idiopathic gonadotropin or luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone (LHRH) deficiency or pituitary-hypothalamic injury from tumors, trauma, or radiation. Delayed puberty: To stimulate puberty in carefully selected males with clearly delayed puberty. Metastatic mammary cancer in women: Used secondarily in women with advancing inoperable metastatic (skeletal) mammary cancer who are 1 to 5 years postmenopausal COVERAGE AUTHORIZATION CRITERIA for the androgen products listed above: 1. Being used for ONE of the following: a. Males for the treatment of hypogonadism (low testosterone): i. patient has symptoms of androgen deficiency AND ii. has a baseline (pre-treatment) morning serum total testosterone level of less than or equal to 300 ng/dL or a serum total testosterone level that is below the testing laboratory’s lower limit of the normal range OR iii. baseline morning serum free testosterone level, measured by the equilibrium dialysis method, of less than or equal to 50 pg/ml or a free serum testosterone level that is below the testing laboratory’s lower limit of the normal range, OR b. -

CASODEX (Bicalutamide)

HIGHLIGHTS OF PRESCRIBING INFORMATION • Gynecomastia and breast pain have been reported during treatment with These highlights do not include all the information needed to use CASODEX 150 mg when used as a single agent. (5.3) CASODEX® safely and effectively. See full prescribing information for • CASODEX is used in combination with an LHRH agonist. LHRH CASODEX. agonists have been shown to cause a reduction in glucose tolerance in CASODEX® (bicalutamide) tablet, for oral use males. Consideration should be given to monitoring blood glucose in Initial U.S. Approval: 1995 patients receiving CASODEX in combination with LHRH agonists. (5.4) -------------------------- RECENT MAJOR CHANGES -------------------------- • Monitoring Prostate Specific Antigen (PSA) is recommended. Evaluate Warnings and Precautions (5.2) 10/2017 for clinical progression if PSA increases. (5.5) --------------------------- INDICATIONS AND USAGE -------------------------- ------------------------------ ADVERSE REACTIONS ----------------------------- • CASODEX 50 mg is an androgen receptor inhibitor indicated for use in Adverse reactions that occurred in more than 10% of patients receiving combination therapy with a luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone CASODEX plus an LHRH-A were: hot flashes, pain (including general, back, (LHRH) analog for the treatment of Stage D2 metastatic carcinoma of pelvic and abdominal), asthenia, constipation, infection, nausea, peripheral the prostate. (1) edema, dyspnea, diarrhea, hematuria, nocturia, and anemia. (6.1) • CASODEX 150 mg daily is not approved for use alone or with other treatments. (1) To report SUSPECTED ADVERSE REACTIONS, contact AstraZeneca Pharmaceuticals LP at 1-800-236-9933 or FDA at 1-800-FDA-1088 or ---------------------- DOSAGE AND ADMINISTRATION ---------------------- www.fda.gov/medwatch The recommended dose for CASODEX therapy in combination with an LHRH analog is one 50 mg tablet once daily (morning or evening). -

(12) STANDARD PATENT (11) Application No. AU 2015336929 B2 (19) AUSTRALIAN PATENT OFFICE

(12) STANDARD PATENT (11) Application No. AU 2015336929 B2 (19) AUSTRALIAN PATENT OFFICE (54) Title Methods of reducing mammographic breast density and/or breast cancer risk (51) International Patent Classification(s) A61K 31/568 (2006.01) A61K 31/585 (2006.01) A61K 31/4196 (2006.01) A61P 35/00 (2006.01) A61K 31/5685 (2006.01) A61P 43/00 (2006.01) (21) Application No: 2015336929 (22) Date of Filing: 2015.10.22 (87) WIPO No: W016/061615 (30) Priority Data (31) Number (32) Date (33) Country 62/067,297 2014.10.22 US (43) Publication Date: 2016.04.28 (44) Accepted Journal Date: 2021.03.18 (71) Applicant(s) Havah Therapeutics Pty Ltd (72) Inventor(s) Birrell, Stephen Nigel (74) Agent / Attorney Adams Pluck, Suite 4, Level 3 20 George Street, Hornsby, NSW, 2077, AU (56) Related Art WO 2002/009721 Al MOUSA, N.A. et al. "Aromatase inhibitors and mammographic breast density in postmenopausal women receiving hormone therapy" Menopause: The Journal of The North American Menopause Society (2008) Vol.15 No.5, pages 875 to 884 WO 2009/036566 Al SMITH, J. et al. "A Pilot Study of Letrozole for One Year in Women at Enhanced Risk of Developing Breast Cancer: Effects on Mammographic Density" Anticancer Research (2012) Vol.32 No.4, pages 1327 to 1332 OUIMET-OLIVA, D. et al. Canadian Association of Radiologists Journal (1981) Vol.32 No.3, pages 159 to 161 (see online PubMed Abstract PMID: 7298699) (12) INTERNATIONAL APPLICATION PUBLISHED UNDER THE PATENT COOPERATION TREATY (PCT) (19) World Intellectual Property Organization International Bureau (10) International -

Campro Catalog Stable Isotope

Introduction & Welcome Dear Valued Customer, We are pleased to present to you our Stable Isotopes Catalog which contains more than three thousand (3000) high quality labeled compounds. You will find new additions that are beneficial for your research. Campro Scientific is proud to work together with Isotec, Inc. for the distribution and marketing of their stable isotopes. We have been working with Isotec for more than twenty years and know that their products meet the highest standard. Campro Scientific was founded in 1981 and we provide services to some of the most prestigious universities, research institutes and laboratories throughout Europe. We are a research-oriented company specialized in supporting the requirements of the scientific community. We are the exclusive distributor of some of the world’s leading producers of research chemicals, radioisotopes, stable isotopes and environmental standards. We understand the requirements of our customers, and work every day to fulfill them. In working with us you are guaranteed to receive: - Excellent customer service - High quality products - Dependable service - Efficient distribution The highly educated staff at Campro’s headquarters and sales office is ready to assist you with your questions and product requirements. Feel free to call us at any time. Sincerely, Dr. Ahmad Rajabi General Manager 180/280 = unlabeled 185/285 = 15N labeled 181/281 = double labeled (13C+15N, 13C+D, 15N+18O etc.) 186/286 = 12C labeled 182/282 = d labeled 187/287 = 17O labeled 183/283 = 13C labeleld 188/288 = 18O labeled 184/284 = 16O labeled, 14N labeled 189/289 = Noble Gases Table of Contents Ordering Information.................................................................................................. page 4 - 5 Packaging Information .............................................................................................. -

COVID-19—The Potential Beneficial Therapeutic Effects of Spironolactone During SARS-Cov-2 Infection

pharmaceuticals Review COVID-19—The Potential Beneficial Therapeutic Effects of Spironolactone during SARS-CoV-2 Infection Katarzyna Kotfis 1,* , Kacper Lechowicz 1 , Sylwester Drozd˙ zal˙ 2 , Paulina Nied´zwiedzka-Rystwej 3 , Tomasz K. Wojdacz 4, Ewelina Grywalska 5 , Jowita Biernawska 6, Magda Wi´sniewska 7 and Miłosz Parczewski 8 1 Department of Anesthesiology, Intensive Therapy and Acute Intoxications, Pomeranian Medical University in Szczecin, 70-111 Szczecin, Poland; [email protected] 2 Department of Pharmacokinetics and Monitored Therapy, Pomeranian Medical University, 70-111 Szczecin, Poland; [email protected] 3 Institute of Biology, University of Szczecin, 71-412 Szczecin, Poland; [email protected] 4 Independent Clinical Epigenetics Laboratory, Pomeranian Medical University, 71-252 Szczecin, Poland; [email protected] 5 Department of Clinical Immunology and Immunotherapy, Medical University of Lublin, 20-093 Lublin, Poland; [email protected] 6 Department of Anesthesiology and Intensive Therapy, Pomeranian Medical University in Szczecin, 71-252 Szczecin, Poland; [email protected] 7 Clinical Department of Nephrology, Transplantology and Internal Medicine, Pomeranian Medical University, 70-111 Szczecin, Poland; [email protected] 8 Department of Infectious, Tropical Diseases and Immune Deficiency, Pomeranian Medical University in Szczecin, 71-455 Szczecin, Poland; [email protected] * Correspondence: katarzyna.kotfi[email protected]; Tel.: +48-91-466-11-44 Abstract: In March 2020, coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) caused by SARS-CoV-2 was declared Citation: Kotfis, K.; Lechowicz, K.; a global pandemic by the World Health Organization (WHO). The clinical course of the disease is Drozd˙ zal,˙ S.; Nied´zwiedzka-Rystwej, unpredictable but may lead to severe acute respiratory infection (SARI) and pneumonia leading to P.; Wojdacz, T.K.; Grywalska, E.; acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS). -

Hormonal Treatment Strategies Tailored to Non-Binary Transgender Individuals

Journal of Clinical Medicine Review Hormonal Treatment Strategies Tailored to Non-Binary Transgender Individuals Carlotta Cocchetti 1, Jiska Ristori 1, Alessia Romani 1, Mario Maggi 2 and Alessandra Daphne Fisher 1,* 1 Andrology, Women’s Endocrinology and Gender Incongruence Unit, Florence University Hospital, 50139 Florence, Italy; [email protected] (C.C); jiska.ristori@unifi.it (J.R.); [email protected] (A.R.) 2 Department of Experimental, Clinical and Biomedical Sciences, Careggi University Hospital, 50139 Florence, Italy; [email protected]fi.it * Correspondence: fi[email protected] Received: 16 April 2020; Accepted: 18 May 2020; Published: 26 May 2020 Abstract: Introduction: To date no standardized hormonal treatment protocols for non-binary transgender individuals have been described in the literature and there is a lack of data regarding their efficacy and safety. Objectives: To suggest possible treatment strategies for non-binary transgender individuals with non-standardized requests and to emphasize the importance of a personalized clinical approach. Methods: A narrative review of pertinent literature on gender-affirming hormonal treatment in transgender persons was performed using PubMed. Results: New hormonal treatment regimens outside those reported in current guidelines should be considered for non-binary transgender individuals, in order to improve psychological well-being and quality of life. In the present review we suggested the use of hormonal and non-hormonal compounds, which—based on their mechanism of action—could be used in these cases depending on clients’ requests. Conclusion: Requests for an individualized hormonal treatment in non-binary transgender individuals represent a future challenge for professionals managing transgender health care. For each case, clinicians should balance the benefits and risks of a personalized non-standardized treatment, actively involving the person in decisions regarding hormonal treatment. -

Annex D to the Report of the Panel to Be Found in Document WT/DS320/R

WORLD TRADE WT/DS320/R/Add.4 31 March 2008 ORGANIZATION (08-0902) Original: English UNITED STATES – CONTINUED SUSPENSION OF OBLIGATIONS IN THE EC – HORMONES DISPUTE Report of the Panel Addendum This addendum contains Annex D to the Report of the Panel to be found in document WT/DS320/R. The other annexes can be found in the following addenda: – Annex A: Add.1 – Annex B: Add.2 – Annex C: Add.3 – Annex E: Add.5 – Annex F: Add.6 – Annex G: Add.7 WT/DS320/R/Add.4 Page D-1 ANNEX D REPLIES OF THE SCIENTIFIC EXPERTS TO QUESTIONS POSED BY THE PANEL A. GENERAL DEFINITIONS 1. Please provide brief and basic definitions for the six hormones at issue (oestradiol-17β, progesterone, testosterone, trenbolone acetate, zeranol, and melengestrol acetate), indicating the source of the definition where applicable. Dr. Boisseau 1. Oestradiol-17β is the most active of the oestrogens hormone produced mainly by the developing follicle of the ovary in adult mammalian females but also by the adrenals and the testis. This 18-carbon steroid hormone is mainly administered as such or as benzoate ester alone (24 or 45 mg for cattle) or in combination (20 mg) with testosterone propionate (200 mg for heifers), progesterone (200 mg for heifers and steers) and trenbolone (200 mg and 40 mg oestradiol-17β for steers) by a subcutaneous implant to the base of the ear to improve body weight and feed conversion in cattle. The ear is discarded at slaughter. 2. Progesterone is a hormone produced primarily by the corpus luteum in the ovary of adult mammalian females. -

Effect of Dehydroepiandrosterone and Testosterone Supplementation on Systemic Lipolysis

ORIGINAL ARTICLE Effect of Dehydroepiandrosterone and Testosterone Supplementation on Systemic Lipolysis Ana E. Espinosa De Ycaza, Robert A. Rizza, K. Sreekumaran Nair, and Michael D. Jensen Division of Endocrinology, Endocrine Research Unit, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minnesota 55905 Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/jcem/article/101/4/1719/2804555 by guest on 24 September 2021 Context: Dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) and T hormones are advertised as antiaging, antiobe- sity products. However, the evidence that these hormones have beneficial effects on adipose tissue metabolism is limited. Objective: The objective of the study was to determine the effect of DHEA and T supplementation on systemic lipolysis during a mixed-meal tolerance test (MMTT) and an iv glucose tolerance test (IVGTT). Design: This was a 2-year randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Setting: The study was conducted at a general clinical research center. Participants: Sixty elderly women with low DHEA concentrations and 92 elderly men with low DHEA and bioavailable T concentrations participated in the study. Interventions: Elderly women received 50 mg DHEA (n ϭ 30) or placebo (n ϭ 30). Elderly men received 75 mg DHEA (n ϭ 30),5mgT(nϭ 30), or placebo (n ϭ 32). Main Outcome Measures: In vivo measures of systemic lipolysis (palmitate rate of appearance) during a MMTT or IVGTT. Results: At baseline there was no difference in insulin suppression of lipolysis measured during MMTT and IVGTT between the treatment groups and placebo. For both sexes, a univariate analysis showed no difference in changes in systemic lipolysis during the MMTT or IVGTT in the DHEA group and T group when compared with placebo. -

Properties and Units in Clinical Pharmacology and Toxicology

Pure Appl. Chem., Vol. 72, No. 3, pp. 479–552, 2000. © 2000 IUPAC INTERNATIONAL FEDERATION OF CLINICAL CHEMISTRY AND LABORATORY MEDICINE SCIENTIFIC DIVISION COMMITTEE ON NOMENCLATURE, PROPERTIES, AND UNITS (C-NPU)# and INTERNATIONAL UNION OF PURE AND APPLIED CHEMISTRY CHEMISTRY AND HUMAN HEALTH DIVISION CLINICAL CHEMISTRY SECTION COMMISSION ON NOMENCLATURE, PROPERTIES, AND UNITS (C-NPU)§ PROPERTIES AND UNITS IN THE CLINICAL LABORATORY SCIENCES PART XII. PROPERTIES AND UNITS IN CLINICAL PHARMACOLOGY AND TOXICOLOGY (Technical Report) (IFCC–IUPAC 1999) Prepared for publication by HENRIK OLESEN1, DAVID COWAN2, RAFAEL DE LA TORRE3 , IVAN BRUUNSHUUS1, MORTEN ROHDE1, and DESMOND KENNY4 1Office of Laboratory Informatics, Copenhagen University Hospital (Rigshospitalet), Copenhagen, Denmark; 2Drug Control Centre, London University, King’s College, London, UK; 3IMIM, Dr. Aiguader 80, Barcelona, Spain; 4Dept. of Clinical Biochemistry, Our Lady’s Hospital for Sick Children, Crumlin, Dublin 12, Ireland #§The combined Memberships of the Committee and the Commission (C-NPU) during the preparation of this report (1994–1996) were as follows: Chairman: H. Olesen (Denmark, 1989–1995); D. Kenny (Ireland, 1996); Members: X. Fuentes-Arderiu (Spain, 1991–1997); J. G. Hill (Canada, 1987–1997); D. Kenny (Ireland, 1994–1997); H. Olesen (Denmark, 1985–1995); P. L. Storring (UK, 1989–1995); P. Soares de Araujo (Brazil, 1994–1997); R. Dybkær (Denmark, 1996–1997); C. McDonald (USA, 1996–1997). Please forward comments to: H. Olesen, Office of Laboratory Informatics 76-6-1, Copenhagen University Hospital (Rigshospitalet), 9 Blegdamsvej, DK-2100 Copenhagen, Denmark. E-mail: [email protected] Republication or reproduction of this report or its storage and/or dissemination by electronic means is permitted without the need for formal IUPAC permission on condition that an acknowledgment, with full reference to the source, along with use of the copyright symbol ©, the name IUPAC, and the year of publication, are prominently visible. -

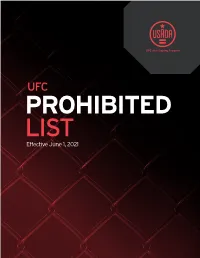

UFC PROHIBITED LIST Effective June 1, 2021 the UFC PROHIBITED LIST

UFC PROHIBITED LIST Effective June 1, 2021 THE UFC PROHIBITED LIST UFC PROHIBITED LIST Effective June 1, 2021 PART 1. Except as provided otherwise in PART 2 below, the UFC Prohibited List shall incorporate the most current Prohibited List published by WADA, as well as any WADA Technical Documents establishing decision limits or reporting levels, and, unless otherwise modified by the UFC Prohibited List or the UFC Anti-Doping Policy, Prohibited Substances, Prohibited Methods, Specified or Non-Specified Substances and Specified or Non-Specified Methods shall be as identified as such on the WADA Prohibited List or WADA Technical Documents. PART 2. Notwithstanding the WADA Prohibited List and any otherwise applicable WADA Technical Documents, the following modifications shall be in full force and effect: 1. Decision Concentration Levels. Adverse Analytical Findings reported at a concentration below the following Decision Concentration Levels shall be managed by USADA as Atypical Findings. • Cannabinoids: natural or synthetic delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) or Cannabimimetics (e.g., “Spice,” JWH-018, JWH-073, HU-210): any level • Clomiphene: 0.1 ng/mL1 • Dehydrochloromethyltestosterone (DHCMT) long-term metabolite (M3): 0.1 ng/mL • Selective Androgen Receptor Modulators (SARMs): 0.1 ng/mL2 • GW-1516 (GW-501516) metabolites: 0.1 ng/mL • Epitrenbolone (Trenbolone metabolite): 0.2 ng/mL 2. SARMs/GW-1516: Adverse Analytical Findings reported at a concentration at or above the applicable Decision Concentration Level but under 1 ng/mL shall be managed by USADA as Specified Substances. 3. Higenamine: Higenamine shall be a Prohibited Substance under the UFC Anti-Doping Policy only In-Competition (and not Out-of- Competition). -

Reproductive DHEA-S

Reproductive DHEA-S Analyte Information - 1 - DHEA-S Introduction DHEA-S, DHEA sulfate or dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate, it is a metabolite of dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) resulting from the addition of a sulfate group. It is the sulfate form of aromatic C19 steroid with 10,13-dimethyl, 3-hydroxy group and 17-ketone. Its chemical name is 3β-hydroxy-5-androsten-17-one sulfate, its summary formula is C19H28O5S and its molecular weight (Mr) is 368.5 Da. The structural formula of DHEA-S is shown in (Fig.1). Fig.1: Structural formula of DHEA-S Other names used for DHEA-S include: Dehydroisoandrosterone sulfate, (3beta)-3- (sulfooxy), androst-5-en-17-one, 3beta-hydroxy-androst-5-en-17-one hydrogen sulfate, Prasterone sulfate and so on. As DHEA-S is very closely connected with DHEA, both hormones are mentioned together in the following text. Biosynthesis DHEA-S is the major C19 steroid and is a precursor in testosterone and estrogen biosynthesis. DHEA-S originates almost exclusively in the zona reticularis of the adrenal cortex (Fig.2). Some may be produced by the testes, none is produced by the ovaries. The adrenal gland is the sole source of this steroid in women, whereas in men the testes secrete 5% of DHEA-S and 10 – 20% of DHEA. The production of DHEA-S and DHEA is regulated by adrenocorticotropin (ACTH). Corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH) and, to a lesser extent, arginine vasopressin (AVP) stimulate the release of adrenocorticotropin (ACTH) from the anterior pituitary gland (Fig.3). In turn, ACTH stimulates the adrenal cortex to secrete DHEA and DHEA-S, in addition to cortisol.