Cancer Research Product Guide | Edition 3

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

METACYC ID Description A0AR23 GO:0004842 (Ubiquitin-Protein Ligase

Electronic Supplementary Material (ESI) for Integrative Biology This journal is © The Royal Society of Chemistry 2012 Heat Stress Responsive Zostera marina Genes, Southern Population (α=0. -

Introduction of Human Telomerase Reverse Transcriptase to Normal Human Fibroblasts Enhances DNA Repair Capacity

Vol. 10, 2551–2560, April 1, 2004 Clinical Cancer Research 2551 Introduction of Human Telomerase Reverse Transcriptase to Normal Human Fibroblasts Enhances DNA Repair Capacity Ki-Hyuk Shin,1 Mo K. Kang,1 Erica Dicterow,1 INTRODUCTION Ayako Kameta,1 Marcel A. Baluda,1 and Telomerase, which consists of the catalytic protein subunit, No-Hee Park1,2 human telomerase reverse transcriptase (hTERT), the RNA component of telomerase (hTR), and several associated pro- 1School of Dentistry and 2Jonsson Comprehensive Cancer Center, University of California, Los Angeles, California teins, has been primarily associated with maintaining the integ- rity of cellular DNA telomeres in normal cells (1, 2). Telomer- ase activity is correlated with the expression of hTERT, but not ABSTRACT with that of hTR (3, 4). Purpose: From numerous reports on proteins involved The involvement of DNA repair proteins in telomere main- in DNA repair and telomere maintenance that physically tenance has been well documented (5–8). In eukaryotic cells, associate with human telomerase reverse transcriptase nonhomologous end-joining requires a DNA ligase and the (hTERT), we inferred that hTERT/telomerase might play a DNA-activated protein kinase, which is recruited to the DNA role in DNA repair. We investigated this possibility in nor- ends by the DNA-binding protein Ku. Ku binds to hTERT mal human oral fibroblasts (NHOF) with and without ec- without the need for telomeric DNA or hTR (9), binds the topic expression of hTERT/telomerase. telomere repeat-binding proteins TRF1 (10) and TRF2 (11), and Experimental Design: To study the effect of hTERT/ is thought to regulate the access of telomerase to telomere DNA telomerase on DNA repair, we examined the mutation fre- ends (12, 13). -

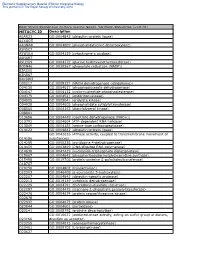

Gene Symbol Gene Description ACVR1B Activin a Receptor, Type IB

Table S1. Kinase clones included in human kinase cDNA library for yeast two-hybrid screening Gene Symbol Gene Description ACVR1B activin A receptor, type IB ADCK2 aarF domain containing kinase 2 ADCK4 aarF domain containing kinase 4 AGK multiple substrate lipid kinase;MULK AK1 adenylate kinase 1 AK3 adenylate kinase 3 like 1 AK3L1 adenylate kinase 3 ALDH18A1 aldehyde dehydrogenase 18 family, member A1;ALDH18A1 ALK anaplastic lymphoma kinase (Ki-1) ALPK1 alpha-kinase 1 ALPK2 alpha-kinase 2 AMHR2 anti-Mullerian hormone receptor, type II ARAF v-raf murine sarcoma 3611 viral oncogene homolog 1 ARSG arylsulfatase G;ARSG AURKB aurora kinase B AURKC aurora kinase C BCKDK branched chain alpha-ketoacid dehydrogenase kinase BMPR1A bone morphogenetic protein receptor, type IA BMPR2 bone morphogenetic protein receptor, type II (serine/threonine kinase) BRAF v-raf murine sarcoma viral oncogene homolog B1 BRD3 bromodomain containing 3 BRD4 bromodomain containing 4 BTK Bruton agammaglobulinemia tyrosine kinase BUB1 BUB1 budding uninhibited by benzimidazoles 1 homolog (yeast) BUB1B BUB1 budding uninhibited by benzimidazoles 1 homolog beta (yeast) C9orf98 chromosome 9 open reading frame 98;C9orf98 CABC1 chaperone, ABC1 activity of bc1 complex like (S. pombe) CALM1 calmodulin 1 (phosphorylase kinase, delta) CALM2 calmodulin 2 (phosphorylase kinase, delta) CALM3 calmodulin 3 (phosphorylase kinase, delta) CAMK1 calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase I CAMK2A calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase (CaM kinase) II alpha CAMK2B calcium/calmodulin-dependent -

Telomeres.Pdf

Telomeres Secondary article Elizabeth H Blackburn, University of California, San Francisco, California, USA Article Contents . Introduction Telomeres are specialized DNA–protein structures that occur at the ends of eukaryotic . The Replication Paradox chromosomes. A special ribonucleoprotein enzyme called telomerase is required for the . Structure of Telomeres synthesis and maintenance of telomeric DNA. Synthesis of Telomeric DNA by Telomerase . Functions of Telomeres Introduction . Telomere Homeostasis . Alternatives to Telomerase-generated Telomeric DNA Telomeres are the specialized chromosomal DNA–protein . Evolution of Telomeres and Telomerase structures that comprise the terminal regions of eukaryotic chromosomes. As discovered through studies of maize and somes. One critical part of this protective function is to fruitfly chromosomes in the 1930s, they are required to provide a means by which the linear chromosomal DNA protect and stabilize the genetic material carried by can be replicated completely, without the loss of terminal eukaryotic chromosomes. Telomeres are dynamic struc- DNA nucleotides from the 5’ end of each strand of this tures, with their terminal DNA being constantly built up DNA. This is necessary to prevent progressive loss of and degraded as dividing cells replicate their chromo- terminal DNA sequences in successive cycles of chromo- somes. One strand of the telomeric DNA is synthesized by somal replication. a specialized ribonucleoprotein reverse transcriptase called telomerase. Telomerase is required for both -

Expression of Telomerase Activity, Human Telomerase RNA, and Telomerase Reverse Transcriptase in Gastric Adenocarcinomas Jinyoung Yoo, M.D., Ph.D., Sonya Y

Expression of Telomerase Activity, Human Telomerase RNA, and Telomerase Reverse Transcriptase in Gastric Adenocarcinomas Jinyoung Yoo, M.D., Ph.D., Sonya Y. Park, Seok Jin Kang, M.D., Ph.D., Byung Kee Kim, M.D., Ph.D., Sang In Shim, M.D., Ph.D., Chang Suk Kang, M.D., Ph.D. Department of Pathology, St. Vincent’s Hospital, Catholic University, Suwon, South Korea esis of gastric cancer and may reflect, along with Telomerase is an RNA-dependent DNA polymerase enhanced hTR, the malignant potential of the tu- that synthesizes TTAGGG telomeric DNA onto chro- mor. It is noteworthy that methacarn-fixed tissue mosome ends to compensate for sequence loss dur- cannot as yet substitute for the frozen section in the ing DNA replication. It has been detected in 85–90% TRAP assay. of all primary human cancers, implicating that the telomerase seems to be reactivated in tumors and KEY WORDS: hTR, Stomach cancer, Telomerase, that such activity may play a role in the tumorigenic TERT. process. The purpose of this study was to evaluate Mod Pathol 2003;16(7):700–707 telomerase activity, human telomerase RNA (hTR), and telomerase reverse transcriptase (TERT) in Recent studies of stomach cancer have been di- stomach cancer and to determine their potential rected toward gaining a better understanding of relationships to clinicopathologic parameters. Fro- tumor biology. Molecular analysis has suggested zen and corresponding methacarn-fixed paraffin- that alterations in the structures and functions of embedded tissue samples were obtained from 51 oncogenes and tumor suppressor genes, genetic patients with gastric adenocarcinoma and analyzed instability, as well as the acquisition of cell immor- for telomerase activity by using a TRAPeze ELISA tality may be of relevance in the pathogenesis of kit. -

Saccharomyces Rrm3p, a 5 to 3 DNA Helicase That Promotes Replication

Downloaded from genesdev.cshlp.org on September 24, 2021 - Published by Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press Saccharomyces Rrm3p, a 5 to 3 DNA helicase that promotes replication fork progression through telomeric and subtelomeric DNA Andreas S. Ivessa,1 Jin-Qiu Zhou,1,2 Vince P. Schulz, Ellen K. Monson, and Virginia A. Zakian3 Department of Molecular Biology, Princeton University, Princeton, New Jersey 08544-1014, USA In wild-type Saccharomyces cerevisiae, replication forks slowed during their passage through telomeric C1–3A/TG1–3 tracts. This slowing was greatly exacerbated in the absence of RRM3, shown here to encode a 5 ,to 3 DNA helicase. Rrm3p-dependent fork progression was seen at a modified Chromosome VII-L telomere at the natural X-bearing Chromosome III-L telomere, and at Y-bearing telomeres. Loss of Rrm3p also resulted in replication fork pausing at specific sites in subtelomeric DNA, such as at inactive replication origins, and at internal tracts of C1–3A/TG1–3 DNA. The ATPase/helicase activity of Rrm3p was required for its role in telomeric and subtelomeric DNA replication. Because Rrm3p was telomere-associated in vivo, it likely has a direct role in telomere replication. [Key Words: Telomere; helicase; telomerase; replication; RRM3; yeast] Received February 7, 2002; revised version accepted April 10, 2002. Telomeres are the natural ends of eukaryotic chromo- Because conventional DNA polymerases cannot repli- somes. In most organisms, the very ends of chromo- cate the very ends of linear DNA molecules, special somes consist of simple repeated sequences. For ex- mechanisms are required to prevent the loss of terminal ample, Saccharomyces cerevisiae chromosomes end in DNA. -

Fructose Causes Liver Damage, Polyploidy, and Dysplasia in the Setting of Short Telomeres and P53 Loss

H OH metabolites OH Article Fructose Causes Liver Damage, Polyploidy, and Dysplasia in the Setting of Short Telomeres and p53 Loss Christopher Chronowski 1, Viktor Akhanov 1, Doug Chan 2, Andre Catic 1,2 , Milton Finegold 3 and Ergün Sahin 1,4,* 1 Huffington Center on Aging, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, TX 77030, USA; [email protected] (C.C.); [email protected] (V.A.); [email protected] (A.C.) 2 Department of Molecular and Cellular Biology, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, TX 77030, USA; [email protected] 3 Department of Pathology, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, TX 77030, USA; fi[email protected] 4 Department of Physiology and Biophysics, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, TX 77030, USA * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +1-713-798-6685; Fax: +1-713-798-4146 Abstract: Studies in humans and model systems have established an important role of short telomeres in predisposing to liver fibrosis through pathways that are incompletely understood. Recent studies have shown that telomere dysfunction impairs cellular metabolism, but whether and how these metabolic alterations contribute to liver fibrosis is not well understood. Here, we investigated whether short telomeres change the hepatic response to metabolic stress induced by fructose, a sugar that is highly implicated in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. We find that telomere shortening in telomerase knockout mice (TKO) imparts a pronounced susceptibility to fructose as reflected in the activation of p53, increased apoptosis, and senescence, despite lower hepatic fat accumulation in TKO mice compared to wild type mice with long telomeres. The decreased fat accumulation in TKO Citation: Chronowski, C.; Akhanov, is mediated by p53 and deletion of p53 normalizes hepatic fat content but also causes polyploidy, V.; Chan, D.; Catic, A.; Finegold, M.; Sahin, E. -

Supplementary Materials

1 Supplementary Materials: Supplemental Figure 1. Gene expression profiles of kidneys in the Fcgr2b-/- and Fcgr2b-/-. Stinggt/gt mice. (A) A heat map of microarray data show the genes that significantly changed up to 2 fold compared between Fcgr2b-/- and Fcgr2b-/-. Stinggt/gt mice (N=4 mice per group; p<0.05). Data show in log2 (sample/wild-type). 2 Supplemental Figure 2. Sting signaling is essential for immuno-phenotypes of the Fcgr2b-/-lupus mice. (A-C) Flow cytometry analysis of splenocytes isolated from wild-type, Fcgr2b-/- and Fcgr2b-/-. Stinggt/gt mice at the age of 6-7 months (N= 13-14 per group). Data shown in the percentage of (A) CD4+ ICOS+ cells, (B) B220+ I-Ab+ cells and (C) CD138+ cells. Data show as mean ± SEM (*p < 0.05, **p<0.01 and ***p<0.001). 3 Supplemental Figure 3. Phenotypes of Sting activated dendritic cells. (A) Representative of western blot analysis from immunoprecipitation with Sting of Fcgr2b-/- mice (N= 4). The band was shown in STING protein of activated BMDC with DMXAA at 0, 3 and 6 hr. and phosphorylation of STING at Ser357. (B) Mass spectra of phosphorylation of STING at Ser357 of activated BMDC from Fcgr2b-/- mice after stimulated with DMXAA for 3 hour and followed by immunoprecipitation with STING. (C) Sting-activated BMDC were co-cultured with LYN inhibitor PP2 and analyzed by flow cytometry, which showed the mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) of IAb expressing DC (N = 3 mice per group). 4 Supplemental Table 1. Lists of up and down of regulated proteins Accession No. -

Activation of Sphingosine Kinase 1 by ERK1/2Mediated Phosphorylation

The EMBO Journal Vol. 22 No. 20 pp. 5491±5500, 2003 Activation of sphingosine kinase 1 by ERK1/2-mediated phosphorylation Stuart M.Pitson1,2, Paul A.B.Moretti1, second messenger and a ligand for cell-surface receptors Julia R.Zebol1, Helen E.Lynn1, Pu Xia1,3, (Hla et al., 2001; Spiegel and Milstien, 2002). MathewA.Vadas 1,3 and The cellular levels of S1P are controlled by its Binks W.Wattenberg1,4 formation from sphingosine through the activity of sphingosine kinase, and by its degradation by S1P lyase 1Hanson Institute, Division of Human Immunology, Institute of (Van Veldhoven et al., 2000) and S1P phosphatases Medical and Veterinary Science, Frome Road, Adelaide, SA 5000 and (Mandala, 2001). In the basal state, this balance between 3Department of Medicine, Adelaide University, Frome Road, Adelaide, Australia S1P generation and degradation results in low cellular levels of S1P (Pyne and Pyne, 2000). However, when cells 4Present address: James Graham Brown Cancer Center, Dehlia Baxter Research Building, 580 S. Preston Avenue, Louisville, KY 40202, are exposed to speci®c growth factors and other agonists USA like tumour necrosis factor-a (TNFa) or phorbol esters the cellular levels of S1P can increase rapidly and transiently 2Corresponding author e-mail: [email protected] (Pitson et al., 2000b). This results in the triggering of various signalling pathways through as yet unidenti®ed Sphingosine kinase 1 is an agonist-activated signalling intracellular S1P targets, as well as through the engage- enzyme that catalyses the formation of sphingosine ment of cell surface S1P receptors following its release 1-phosphate, a lipid second messenger that has been from cells (Hobson et al., 2001). -

The Architecture of a Eukaryotic Replisome

The Architecture of a Eukaryotic Replisome Jingchuan Sun1,2, Yi Shi3, Roxana E. Georgescu3,4, Zuanning Yuan1,2, Brian T. Chait3, Huilin Li*1,2, Michael E. O’Donnell*3,4 1 Biosciences Department, Brookhaven National Laboratory, Upton, New York, USA 2 Department of Biochemistry & Cell Biology, Stony Brook University, Stony Brook, New York, USA. 3 The Rockefeller University, 1230 York Avenue, New York, New York, USA. 4 Howard Hughes Medical Institute *Correspondence and requests for materials should be addressed to M.O.D. ([email protected]) or H.L. ([email protected]) ABSTRACT At the eukaryotic DNA replication fork, it is widely believed that the Cdc45-Mcm2-7-GINS (CMG) helicase leads the way in front to unwind DNA, and that DNA polymerases (Pol) trail behind the helicase. Here we use single particle electron microscopy to directly image a replisome. Contrary to expectations, the leading strand Pol ε is positioned ahead of CMG helicase, while Ctf4 and the lagging strand Pol α-primase (Pol α) are behind the helicase. This unexpected architecture indicates that the leading strand DNA travels a long distance before reaching Pol ε, it first threads through the Mcm2-7 ring, then makes a U-turn at the bottom to reach Pol ε at the top of CMG. Our work reveals an unexpected configuration of the eukaryotic replisome, suggests possible reasons for this architecture, and provides a basis for further structural and biochemical replisome studies. INTRODUCTION DNA is replicated by a multi-protein machinery referred to as a replisome 1,2. Replisomes contain a helicase to unwind DNA, DNA polymerases that synthesize the leading and lagging strands, and a primase that makes short primed sites to initiate DNA synthesis on both strands. -

Interaction of 6-Phosphofructo-2-Kinase/Fructose-2,6- Bisphosphatase (PFK-2/Fbpase-2) with Glucokinase Activates Glucose Phospho

Interaction of 6-Phosphofructo-2-Kinase/Fructose-2,6- Bisphosphatase (PFK-2/FBPase-2) With Glucokinase Activates Glucose Phosphorylation and Glucose Metabolism in Insulin-Producing Cells Laura Massa,1 Simone Baltrusch,1 David A. Okar,2,3 Alex J. Lange,2 Sigurd Lenzen,1 and Markus Tiedge1 The bifunctional enzyme 6-phosphofructo-2-kinase/ fructose-2,6-bisphosphatase (PFK-2/FBPase-2) was re- cently identified as a new intracellular binding partner he enzyme glucokinase (GK) plays a pivotal role for glucokinase (GK). Therefore, we studied the impor- in the recognition of glucose in pancreatic tance of this interaction for the activity status of GK -cells and the regulation of glucose metabolism and glucose metabolism in insulin-producing cells by Tin the liver (1–7). In pancreatic -cells, GK acts overexpression of the rat liver and pancreatic islet as a glucose sensor and catalyzes the rate-limiting step for isoforms of PFK-2/FBPase-2. PFK-2/FBPase-2 overex- initiation of glucose-induced insulin secretion (6). GK is pression in RINm5F-GK cells significantly increased the regulated in a complex manner in pancreatic -cells by GK activity by 78% in cells expressing the islet isoform, posttranslational modifications of the enzyme protein that by 130% in cells expressing the liver isoform, and by mainly depend on the intracellular glucose concentration 116% in cells expressing a cAMP-insensitive liver S32A/ (8–13). These posttranslational mechanisms of GK activity H258A double mutant isoform. Only in cells overex- regulation are comprised of conformational changes pressing the wild-type liver PFK-2/FBPase-2 isoform (14,15), sulfhydryl-group conversions (16–18), and inter- was the increase of GK activity abolished by forskolin,  apparently due to the regulatory site for phosphoryla- actions with -cell matrix proteins (13,19), insulin gran- tion by a cAMP-dependent protein kinase. -

Novocib Nucleoside Kinases

PRECICE ® Services Information sheet Nucleoside kinases, rate-limiting step of nucleoside analogues activation Nucleoside analogues have proven to be a highly successful class of anti-cancer and anti-viral drugs. The therapeutic efficacy of nucleoside analogues is dependent of their intracellular phosphorylation. Two cellular nucleoside kinases, deoxycytidine kinase (dCK) and UMP-CMP kinase (CMK) are critical for phosphorylation of cytidine analogues. These kinases provide two first steps of activation of highly effective anti-cancer and anti-viral drugs, such as 1-β-D- arabinofuranosylcytosine (araC, aracytidine ), 2’,2’difluorodeoxycytidine (dFdC, gemcitabine ), β-D-2’3’- dideoxycytidine (ddC). Both kinases phosphorylate unnatural L-nucleosides (e.g., β-L-2’3’-dideoxy-3’thiacytidine, L- SSdC, 3-TC or lamividune ). Kinetic constants of araC, dFdC and 3TC phosphorylation by recombinant dCK and UMP-CMPK have been published. The comparison of phosphorylation properties of new nucleoside analogues with those of known drugs provides the rational basis for selection of analogues of better therapeutic potential. To characterize the phosphorylation properties of new nucleoside analogues, Novo CIB has developed human recombinant dCK and human recombinant CMK nucleoside phosphorylation assays. As shown in Table 1, CMK assay must be performed with monophosphate forms of nucleoside analogues and requires preliminary phosphorylation of nucleoside analogues and their purification. To circumvent this time-consuming step, NovoCIB has developed a coupled dCK-CMK nucleoside phosphorylation assay that delivers in one step the critical information on both dCK and CMK substrate properties of nucleoside analogue. Ribavirin (1-β-D-ribofuranosyl-1,2,4-triazole-3-carboxamide) is a purine nucleoside analogue with a broad-spectrum antiviral activity.