The Historic American Engineering Record: Arroyo Seco Parkway

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1952 Big Job the Los Angeles Metropolitan Area LI8RARY by P

:' -s. ~~~ ,,:-~ — ; , --~l~ X52 'lHI~'G'~~'~~WAYS AN D ~a~~rn~ ~►~ ~~~ ~- ~° ~. ~ €~ . ~ ~ ~~ ~ `yi , F t ~ ,y4 r .~y~ F~3 p 1i v .k, _ '. fix.' ~TY M 3- J~ ~ ~+z. ~n#:` . i 4aac~r~ r~( jiY ~ ~ ~',, ~ k ~~i ~ r}~ ~ ~ `. ..~ ti ti j` I~i ~ ` , 7 fY r .- - R.1 i l/ ~i Y ~F i # ~; ~}~ o a ,:..,~,a. ~~ ~,,_ ~{ ~ ..~ ~ ~ ,~ t4 ~ 'i y ~ ~ ~ ~ .~ ~`~~~ F ~v - Q . A .I ~ r.€ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ t ~- - F: .~s . I =~i~' ~ l a~ t . ~'~ .. ~~/ ~ r ~ ~-Y L 5 ~.~~ r i d J~ F `~ M. f~ \X 3- S J ~. ` t ^~'~ '~~ ~' y,~ 1, til. ~~,y,a 3 ~1'~ 7 g}~h } t Y '~}~; t ,;, }Y~ i , ~i Yi ~. i2~ ~ ~ Q ~ ~~ a Y r~ ~ ~ r ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ s ~c 4 fi 4 Itity ~ ~ ^~. \. 3 r,~ Tom .:. 6. ~1.>~ `~4x r ~, 4 Y ~ .[F ~ d~ . -x'x-si. ,BE~t ~,a'j. v~ '~ ~~ :`" ^~i~~ y~. r. S ._, _.— +IwJVW '.~.W~ .~~_._...ar.r.: .~~... _-r~.~yr.. ~..~. ~...r`... ~..~...~~.. ~.~. ___.~~.~. ._.... _~~_- Yv~c~~i' California Highways and Public Works Public Works Building Official 10u'rna I of the Division of Highways, Twelfth and N Streets Department of Public Works, State of California Sacramento FRANK B. DURKEE GEORGE T. McCOY Director State Highway Engineer KENNETH C. ADAMS, Editor HElEN HALSTED, Associate Editor MERRITT R. NICKERSON, Chief Photographer Published in the interest of highway development in Cali fornia. Editors of newspapers and others are privileged to use matter contained herein. Cuts will be gladly loaned upon request. Address communications to CALIFORNIA HIGHWAYS AND PUBLIC WORKS P. O. Box 1499 Sacramento, California Vol. 31 March-April Nos. -

Industrial Context Work Plan

LOS ANGELES CITYWIDE HISTORIC CONTEXT STATEMENT Context: Industrial Development, 1850-1980 Prepared for: City of Los Angeles Department of City Planning Office of Historic Resources September 2011; rev. February 2018 The activity which is the subject of this historic context statement has been financed in part with Federal funds from the National Park Service, Department of the Interior, through the California Office of Historic Preservation. However, the contents and opinions do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the Department of the Interior or the California Office of Historic Preservation, nor does mention of trade names or commercial products constitute endorsement or recommendation by the Department of the Interior or the California Office of Historic Preservation. This program receives Federal financial assistance for identification and protection of historic properties. Under Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973, and the Age Discrimination Act of 1975, as amended, the U.S. Department of the Interior prohibits discrimination on the basis of race, color, national origin, disability, or age in its federally assisted programs. If you believe you have been discriminated against in any program, activity, or facility as described above, or if you desire further information, please write to: Office of Equal Opportunity, National Park Service; 1849 C Street, N.W.; Washington, D.C. 20240 SurveyLA Citywide Historic Context Statement Industrial Development, 1850-1980 TABLE -

Interstate Commerce Commission Washington

INTERSTATE COMMERCE COMMISSION WASHINGTON REPORT NO. 3374 PACIFIC ELECTRIC RAILWAY COMPANY IN BE ACCIDENT AT LOS ANGELES, CALIF., ON OCTOBER 10, 1950 - 2 - Report No. 3374 SUMMARY Date: October 10, 1950 Railroad: Pacific Electric Lo cation: Los Angeles, Calif. Kind of accident: Rear-end collision Trains involved; Freight Passenger Train numbers: Extra 1611 North 2113 Engine numbers: Electric locomo tive 1611 Consists: 2 muitiple-uelt 10 cars, caboose passenger cars Estimated speeds: 10 m. p h, Standing ft Operation: Timetable and operating rules Tracks: Four; tangent; ] percent descending grade northward Weather: Dense fog Time: 6:11 a. m. Casualties: 50 injured Cause: Failure properly to control speed of the following train in accordance with flagman's instructions - 3 - INTERSTATE COMMERCE COMMISSION REPORT NO, 3374 IN THE MATTER OF MAKING ACCIDENT INVESTIGATION REPORTS UNDER THE ACCIDENT REPORTS ACT OF MAY 6, 1910. PACIFIC ELECTRIC RAILWAY COMPANY January 5, 1951 Accident at Los Angeles, Calif., on October 10, 1950, caused by failure properly to control the speed of the following train in accordance with flagman's instructions. 1 REPORT OF THE COMMISSION PATTERSON, Commissioner: On October 10, 1950, there was a rear-end collision between a freight train and a passenger train on the Pacific Electric Railway at Los Angeles, Calif., which resulted in the injury of 48 passengers and 2 employees. This accident was investigated in conjunction with a representative of the Railroad Commission of the State of California. 1 Under authority of section 17 (2) of the Interstate Com merce Act the above-entitled proceeding was referred by the Commission to Commissioner Patterson for consideration and disposition. -

W Huntington Dr, Monrovia, CA 91016

OFFERING MEMORANDUM 601 W Huntington Dr, Monrovia, CA 91016 Excellent location in Monrovia bordered by Arcadia, Pasadena, San Gabriel and San Marino Directly across from a major shopping center. Property Can be Delivered Vacant! Listed by: Marc Schwartz | Vice President Dir:213.362.8500 [email protected] License No. 01515007 601 W HUNTINGTON DR | MONROVIA The Growth Investment Group Marc Schwartz Han Widjaja Chen, CCIM Leo Shaw Vice President President Vice President Dir. 213.362.8500 Dir 626.594.4900 | Fax 626.316.7551 Dir 626.716.6968 [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] License No. 01515007 Broker License No. 01749321 Broker License No. 01879962 Spencer Rands Justin McCardle Arin Gharibian Vice President Vice President Senior Associate Dir 949.303.0290 Dir 909.486.2069 Dir 310.919.6655 [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Broker License No. 01388490 License No. 01895720 License No. 01946372 Matthew Guerra Jeanelle Mountford Ryan Yip Broker Associate Broker Associate Broker Associate Dir 626.898.9740 Dir 626.898.9710 Dir. 626.898.7290 [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] License No. 02022646 License No. 01737872 License No. 02087685 Jackelyn Sutanto Marketing Dir. 626.594.4901 [email protected] DISCLAIMER AND CONFIDENTIALITY AGREEMENT: This is a confidential Memorandum intended solely for your limited use and benefit in determining whether you desire to express further interest in the acquisition of: 601 W HUNTINGTON DR, MONROVIA, CA 91016 (“Property”). This Memorandum contains selected information pertaining to the Property and does not purport to be a representation of the state of affairs of the Owner or the Property, to be all-inclusive or to con- tain all or part of the information that prospective investors may require to evaluate a purchase of real property. -

Eternal Lies Addendum – Local Newspapers

ETERNAL LIES ADDENDUM – LOCAL NEWSPAPERS This addendum to the Alexandrian Remix of Eternal Lies adds historically-sourced local newspapers to all of the major locations of the campaign. I have not researched papers for New York (the PCs spend so little time there; and, if in doubt, use the New York Times) or Thibet (the PCs are in such an isolated location that newspapers are unlikely to be available, except perhaps for an international edition of a paper like the Paris Herald Tribune, as described under Bangkok newspapers). Hitting up the morgues of local papers for leads has become such a standard procedural element for Cthulhu-esque investigators that I probably don’t need to pontificate upon it at any great length here. It should be noted that the original campaign references a number of specific newspapers in which specific articles of note are published; those are generally not mentioned here (although obviously they also exist). The purpose of this resource is to provide a firm foundation for the GM to improvise from when the PCs go off the beaten path and begin performing unanticipated background research. When I originally ran the campaign, I also found that it was not particularly uncommon for the globetrotting PCs to specifically request a local newspaper upon checking into a new hotel. Being able to reference specific papers (with a few personalizing factoids to distinguish one broadsheet from another) proved to be a remarkably effective and immersive technique that can contribute greatly to the meaningful sensation of the campaign moving through space and culture. -

Gold Line Bridge the Art O F Desi Gn

GOLD LINE BRIDGE the Art o F desi Gn Metro Gold Line Foothill Extension Construction Authority 406 E. Huntington Drive, Suite 202 Monrovia, CA 91016 (626) 471-9050 www.foothillextension.org A Metro Gold line Foothill extension ConstrUCtion AUthoritY PROJeCt The mother art is architecture. Without an architecture of our own we have no soul of our own civilization. Frank Lloyd Wright The Gold Line Bridge ProJeCt detAils “The bridge he Gold Line Bridge is a 584-foot bridge that spans the eastbound I-210 Freeway in Arcadia, California. The $18.6 million dual-track bridge is the evokes The greaT T first completed element of the 11.5-mile Metro Gold Line Foothill Extension infrasTrucTure light rail project from Pasadena to Azusa, providing a connection between the designs of The 1930s existing Sierra Madre Villa Station in Pasadena and the future Arcadia Station. Works Progress The Foothill Extension is overseen by the Metro Gold Line Foothill Extension adminisTraTion and Construction Authority, an independent transportation agency responsible for the project’s planning, design, and construction. signals a neW era of the Gold line BridGe: stAtistiCs The Construction Authority, with the involvement of award-winning public arTisT involvemenT artist Andrew Leicester, envisioned the Gold Line Bridge as a vivid expression l ength: (end-to-end): 584 feet in major Public of the community, past and present. This pioneering collaboration resulted in Width: 115 feet between centerlines of the two signature support columns iniTiaTives of our the creation of a sculptural bridge built for the same cost originally estimated for a more conventional structure of its size. -

GOOGLE LLC V. ORACLE AMERICA, INC

(Slip Opinion) OCTOBER TERM, 2020 1 Syllabus NOTE: Where it is feasible, a syllabus (headnote) will be released, as is being done in connection with this case, at the time the opinion is issued. The syllabus constitutes no part of the opinion of the Court but has been prepared by the Reporter of Decisions for the convenience of the reader. See United States v. Detroit Timber & Lumber Co., 200 U. S. 321, 337. SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES Syllabus GOOGLE LLC v. ORACLE AMERICA, INC. CERTIORARI TO THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE FEDERAL CIRCUIT No. 18–956. Argued October 7, 2020—Decided April 5, 2021 Oracle America, Inc., owns a copyright in Java SE, a computer platform that uses the popular Java computer programming language. In 2005, Google acquired Android and sought to build a new software platform for mobile devices. To allow the millions of programmers familiar with the Java programming language to work with its new Android plat- form, Google copied roughly 11,500 lines of code from the Java SE pro- gram. The copied lines are part of a tool called an Application Pro- gramming Interface (API). An API allows programmers to call upon prewritten computing tasks for use in their own programs. Over the course of protracted litigation, the lower courts have considered (1) whether Java SE’s owner could copyright the copied lines from the API, and (2) if so, whether Google’s copying constituted a permissible “fair use” of that material freeing Google from copyright liability. In the proceedings below, the Federal Circuit held that the copied lines are copyrightable. -

Los Angeles Transportation Transit History – South LA

Los Angeles Transportation Transit History – South LA Matthew Barrett Metro Transportation Research Library, Archive & Public Records - metro.net/library Transportation Research Library & Archive • Originally the library of the Los • Transportation research library for Angeles Railway (1895-1945), employees, consultants, students, and intended to serve as both academics, other government public outreach and an agencies and the general public. employee resource. • Partner of the National • Repository of federally funded Transportation Library, member of transportation research starting Transportation Knowledge in 1971. Networks, and affiliate of the National Academies’ Transportation • Began computer cataloging into Research Board (TRB). OCLC’s World Catalog using Library of Congress Subject • Largest transit operator-owned Headings and honoring library, forth largest transportation interlibrary loan requests from library collection after U.C. outside institutions in 1978. Berkeley, Northwestern University and the U.S. DOT’s Volpe Center. • Archive of Los Angeles transit history from 1873-present. • Member of Getty/USC’s L.A. as Subject forum. Accessing the Library • Online: metro.net/library – Library Catalog librarycat.metro.net – Daily aggregated transportation news headlines: headlines.metroprimaryresources.info – Highlights of current and historical documents in our collection: metroprimaryresources.info – Photos: flickr.com/metrolibraryarchive – Film/Video: youtube/metrolibrarian – Social Media: facebook, twitter, tumblr, google+, -

Military Institutions and Activities, 1850-1980

LOS ANGELES CITYWIDE HISTORIC CONTEXT STATEMENT Guidelines for Evaluating Resources Associated with Military Institutions and Activities, 1850-1980 Prepared for: City of Los Angeles Department of City Planning Office of Historic Resources November 2019 SurveyLA Citywide Historic Context Statement Guidelines for Evaluating Resources Associated with Military Institutions and Activities TABLE OF CONTENTS PREFACE 1 CONTRIBUTORS 1 INTRODUCTION 1 Related Contexts and Evaluation Considerations 1 Other Sources for Military Historic Contexts 3 MILITARY INSTITUTIONS AND ACTIVITIES HISTORIC CONTEXT 3 Historical Overview 3 Los Angeles: Mexican Era Settlement to the Civil War 3 Los Angeles Harbor and Coastal Defense Fortifications 4 The Defense Industry in Los Angeles: From World War I to the Cold War 5 World War II and Japanese Forced Removal and Incarceration 8 Recruitment Stations and Military/Veterans Support Services 16 Hollywood: 1930s to the Cold War Era 18 ELIGIBILITY STANDARDS FOR AIR RAID SIRENS 20 ATTACHMENT A: FALLOUT SHELTER LOCATIONS IN LOS ANGELES 1 SurveyLA Citywide Historic Context Statement Guidelines for Evaluating Resources Associated with Military Institutions and Activities PREFACE These “Guidelines for Evaluating Resources Associated with Military Institutions and Activities” (Guidelines) were developed based on several factors. First, the majority of the themes and property types significant in military history in Los Angeles are covered under other contexts and themes of the citywide historic context statement as indicated in the “Introduction” below. Second, many of the city’s military resources are already designated City Historic-Cultural Monuments and/or are listed in the National Register.1 Finally, with the exception of air raid sirens, a small number of military-related resources were identified as part of SurveyLA and, as such, did not merit development of full narrative themes and eligibility standards. -

A Historic Guide to Pasadena

A HISTORIC GUIDE TO PASADENA WELCOME TO CICLAVIA—PASADENA Welcome to CicLAvia Pasadena, our first event held entirely outside of the city of Los Angeles! And we couldn’t have picked a prettier city; OUR PARTNERS bordered by the San Gabriel Mountains and the Arroyo Seco, Pasadena, which means “Crown of the Valley” in the Ojibwa/Chippewa language, has long been known for its beauty and ideal climate. After all, a place best known for a parade of flower-covered floats— OUR SUPPORTERS OUR SPONSORS City of Los Angeles Cirque du Soleil the world-famous Tournament of Roses since Annenberg Foundation Tern Bicycles Ralph M. Parsons Foundation The Laemmle Charitable Foundation 1890—can’t be bad, right? Rosenthal Family Foundation Los Angeles County Bicycle Coalition David Bohnett Foundation Indie Printing Today’s route centers on Colorado Boulevard— Wahoo’s Fish Taco OUR MEDIA PARTNERS Walden School Pasadena’s main east-west artery—a road with a The Los Angeles Times Laemmle Theatres THANKS TO long and rich history. Originally called Colorado 89.3 FM KPCC Public Radio La Grande Orange Café Time Out Los Angeles Old Pasadena Management District Street, the road was named to honor the latest Pasadena Star-News Pasadena Arts Council state to join the Union at the time (1876) and Pasadena Heritage Pasadena Museum of History was changed to “Boulevard” in 1958. The beau- Playhouse District Association South Lake Business Association tiful Colorado Street Bridge, which was built in 1913 and linked the San Gabriel Valley to the San Fernando Valley, still retains the old name. -

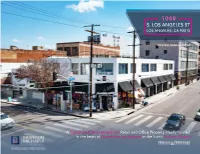

1048 S Los Angeles Street Is Located Less Than Three Miles from the Ferrante, a Massive 1,500-Unit Construction Project, Scheduled for Completion in 2021

OFFERING MEMORANDUM A Signalized Corner Mixed-Use Retail and Office Property Ideally located in the heart of Downtown Los Angeles in the Iconic Fashion District brandonmichaelsgroup.com INVESTMENT ADVISORS Brandon Michaels Senior Managing Director of Investments Senior Director, National Retail Group Tel: 818.212-2794 [email protected] CA License: 01434685 Matthew Luchs First Vice President Investments COO of The Brandon Michaels Group Tel: 818.212.2727 [email protected] CA License: 01948233 Ben Brownstein Senior Investment Associate National Retail Group National Industrial Properties Group Tel: 818.212.2812 [email protected] CA License: 02012808 Contents 04 Executive Summary 10 Property Overview 16 Area Overview 28 FINANCIAL ANALYSIS Executive Summary 4 1048 S. Los Angeles St The Offering A Signalized Corner Mixed-Use Retail and Office Property Ideally located in the heart of Downtown Los Angeles in the Iconic Fashion District The Brandon Michaels Group of Marcus & Millichap has been selected to exclusively represent for sale 1048 South Los Angeles Street, a two-story multi-tenant mixed-use retail and office property ideally located on the Northeast signalized corner of Los Angeles Street and East 11th Street. The property is comprised of 15 rental units, with eight retail units on the ground floor, and seven office units on the second story. 1048 South Los Angeles Street is to undergo a $170 million renovation. currently 86% occupied. Three units are The property is located in the heart of vacant, one of which is on the ground the iconic fashion district of Downtown floor, and two of which are on the Los Angeles, which is home to over second story. -

Historical Society of Southern California Collection -- Charles Puck Collection of Negatives and Photographs: Finding Aid

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/tf2p30028s No online items Historical Society of Southern California Collection -- Charles Puck Collection of Negatives and Photographs: Finding Aid Finding aid prepared by Jennifer Watts. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens Photo Archives 1151 Oxford Road San Marino, California 91108 Phone: (626) 405-2191 Email: [email protected] URL: http://www.huntington.org © August 1999 The Huntington Library. All rights reserved. Historical Society of Southern photCL 400 volume 2 & volume 3 1 California Collection -- Charles Puck Collection of Negatives a... Overview of the Collection Title: Historical Society of Southern California Collection -- Charles Puck Collection of Negatives and Photographs Dates (inclusive): 1864-1963 Bulk dates: 1920s-1950s Collection Number: photCL 400 volume 2 & volume 3 Creator: Puck, Charles, 1882-1968 Extent: 11,400 photographs in 42 boxes (30.29 linear feet) Repository: The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens. Photo Archives 1151 Oxford Road San Marino, California 91108 Phone: (626) 405-2191 Email: [email protected] URL: http://www.huntington.org Abstract: The Puck Collection consists of more than 11,000 photographs and negatives both taken and collected by Los Angeles resident and local history enthusiast Charles Puck (1882-1968), which he donated to the Historical Society of Southern California over more than twenty years in the mid-20th century. The photographs date from 1864 to 1963 (bulk 1920s-1950s) and depict buildings, monuments, civic happenings, modes of transportation, flora and fauna, and anything else that captured his particular interests. Puck compiled several scrapbooks on topics such as adobes and buildings of Los Angeles, illustrating them with his photographs and annotating them with historical anecdotes and personal recollections.