'Left-Over' Spaces of State-Socialism in Bucharest

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Agentii Loto La Data De 30.04.2021 Site Loto.Xlsx

Simbol Localitate / Oras / Sector Judet Adresa agentie Tip Agentie Agentie (ORAS; COMUNA; SECTOR) 01-001 ALBA Alba-Iulia Municipiul Alba-Iulia, P-ta Iuliu Maniu, bl.280 proprie Localitatea Baia de Aries, Oras Baia de Aries, Str. 01-002 ALBA Baia de Aries proprie Piata Baii nr. 1 Bloc D9, etaj P, ap.XII, judet Alba 01-004 ALBA Abrud Oras Abrud, Piata Eroilor nr.7 proprie 01-005 ALBA Aiud Municipiul Aiud, Str. Transilvaniei, bloc A7, SPATIU proprie MUNICIPIUL BLAJ, B-dul Republicii nr. 15, ap.2 01-007 ALBA Blaj proprie (PUNCT DE LUCRU BLAJ) ORAS CAMPENI, Str. Avram Iancu, bloc 2A1 Ap. 01-008 ALBA Campeni proprie XIII, (AGENTIE LOTO PRONO) 01-009 ALBA Cugir Oras Cugir, Str. 21 Decembrie 1989, nr.1E proprie ORAS OCNA MURES, Str. N Iorga nr. 18A, ap. 2, 01-010 ALBA Ocna Mures proprie (AGENTIE LOTO PRONO) 01-011 ALBA Aiud Municipiul Aiud, Strada Unirii, bl. 57/C proprie 01-013 ALBA Sebes Municipiul Sebes, Str. Lucian Blaga nr. 24 proprie 01-015 ALBA Teius Oras Teius, Str. Clujului, Spatiul nr. 11, Bl. A2, proprie 01-016 ALBA Alba-Iulia Municipiul Alba Iulia, Str. B-dul Transilvaniei nr.9A proprie Municipiul Alba-Iulia, Str. Piata Iuliu Maniu nr. 4 etaj 01-019 ALBA Alba-Iulia proprie P 01-020 ALBA Sebes Municipiul Sebes, Str. Lucian Blaga nr. 81 proprie Municipiul Blaj, Str. Eroilor, bl. 27, parter, AGENTIE 01-021 ALBA Blaj proprie LOTO PRONO 01-022 ALBA Cugir Oras Cugir, Str. 21 Decembrie 1989, nr.HD1 proprie MUNICIPIUL ALBA IULIA, B-dul Transilvaniei nr. -

Historical GIS: Mapping the Bucharest Geographies of the Pre-Socialist Industry Gabriel Simion*, Alina Mareci, Florin Zaharia, Radu Dumitru

# Gabriel Simion et al. Human Geographies – Journal of Studies and Research in Human Geography Vol. 10, No. 2, November 2016 | www.humangeographies.org.ro ISSN–print: 1843–6587 | ISSN–online: 2067–2284 Historical GIS: mapping the Bucharest geographies of the pre-socialist industry Gabriel Simion*, Alina Mareci, Florin Zaharia, Radu Dumitru University of Bucharest, Romania This article aims to map the manner in which the rst industrial units crystalized in Bucharest and their subsequent dynamic. Another phenomenon considered was the way industrial sites grew and propagated and how the rst industrial clusters formed, thus amplifying the functional variety of the city. The analysis was undertaken using Historical GIS, which allowed to integrate elements of industrial history with the location of the most important industrial objectives. Working in GIS meant creating a database with the existing factories in Bucharest, but also those that had existed in different periods. Integrating the historical with the spatial information about industry in Bucharest was preceded by thorough preparations, which included geo-referencing sources (city plans and old maps) and rectifying them. This research intends to serve as an example of how integrating past and present spatial data allows for the analysis of an already concluded phenomenon and also explains why certain present elements got to their current state.. Key Words: historical GIS, GIS dataset, Bucharest. Article Info: Received: September 5, 2016; Revised: October 24, 2016; Accepted: November 15, 2016; Online: November 30, 2016. Introduction The spatial evolution of cities starting with the ending of the 19th century and the beginning of the 20th is closely connected to their industrial development. -

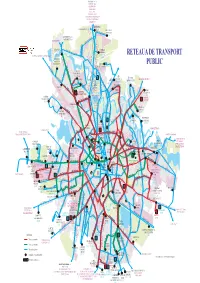

RETEA GENERALA 01.07.2021.Cdr

OTOPENI 780 783 OSTRATU R441 OTOPENI R442 PERIS R443 PISCU R444 GRUIU R446 R447 MICSUNESTII MARI R447B MOARA VLASIEI R448 SITARU 477 GREENFIELD STRAULESTI 204 304 203 204 Aleea PrivighetorilorJOLIE VILLE BANEASA 301 301 301 GREENFIELD 204 BUFTEA R436 PIATA PRESEI 304 131 Str. Jandarmeriei261 304 STRAULESTI Sos. Gh. Ionescu COMPLEX 97 204 205 304 261 Sisesti BANEASA RETEAUA DE TRANSPORT R402 205 131 261 335 BUFTEA GRADISTEA SITARU R402 261 205 R402 R436 Bd. OaspetilorStr. Campinita 361 605 COMPLEX 112 205 261 97 131 261301 COMERCIAL Sos. Bucuresti Ploiesti PUBLIC COLOSSEUM CARTIER 231 Sos. Chitilei Bd. Bucurestii Noi Sos. Straulesti R447 R447B R448 R477 203 335 361 605 780 783 112 R441 R442 R443 R444HENRI R446 COANDA 231 Bd. Aerogarii R402 97 605 231 112 112 CARTIER 112 301 112 DAMAROAIA 131 R436 335 231 Sos. Chitilei R402 24 331R436 CFR Str. Alex. Serbanescu 112 CONSTANTA CARTIER MERII PETCHII R409 112 DRIDU Str. N. Caramfil R402 Bd. Laminorului AUTOBAZA ANDRONACHE 331 65 86 112 135 243 Bd. NORDULUI112 301 382 Bd. Gloriei24 Str. Jiului 605 Sos. 112Pipera 135 Sos. Chitilei Poligrafiei PIATA PLATFORMA Bd. BucurestiiPajurei Noi 231 243 Str. Peris MEZES 780 783 INDUSTRIALA Str. PRESEI Str.Oi 3 45 65 86 331 243 3 45 382 PASAJ Sos. Bucuresti Ploiesti 3 41 243 PIPERA 382 DEPOUL R447 R447BR448 R477 112 231 243 i 65 86 97 243 16 36 COLENTINA 131105 203 205 261203 304 231 261 304 330 135 343 n tuz BUCURESTII NOI a R441 R442 R443 c 21 i CARTIER 605 tr 231R441 361 R442 783 R443 R444 R446 DEPOUL Bd. -

34516 Stanciu Ion Soseaua Oltenitei Nr. 55, Bloc 2, Scara 3, Apt

34516 STANCIU ION SOSEAUA OLTENITEI NR. 55, BLOC 2, SCARA 3, APT. 102, Decizie de impunere 290424 05.03.2021 MUNICIPIUL BUCURESTI, SECTORUL 4, SUB. 10 34517 DUMITRU MARIAN DRUMUL BINELUI NR. 211-213, BLOC VILA A2, MUNICIPIUL Decizie de impunere 214609 05.03.2021 BUCURESTI, SECTORUL 4, SUB. 6 34518 DUMITRU MARIAN DRUMUL BINELUI NR. 211-213, BLOC VILA A2, MUNICIPIUL Decizie de impunere 358763 05.03.2021 BUCURESTI, SECTORUL 4, SUB. 6 34519 DUMITRU MIRELA-ROXANA DRUMUL BINELUI NR. 211-213, BLOC VILA A2, MUNICIPIUL Decizie de impunere 281881 05.03.2021 BUCURESTI, SECTORUL 4, SUB. 6 34520 ZANFIROAIA CLAUDIA STRADA RAUL SOIMULUI NR. 4, BLOC 47, SCARA 5, ETAJ Decizie de impunere 303649 05.03.2021 2, APT. 69, MUNICIPIUL BUCURESTI, SECTORUL 4, SUB. 10 34521 DINCA GABRIELA-FLORICA STRADA STRAJA NR. 12, BLOC 52, SCARA 2, ETAJ 5, APT. Decizie de impunere 333194 05.03.2021 96, MUNICIPIUL BUCURESTI, SECTORUL 4, SUB. 10 34522 COVACI CIPRIAN ANDREI STRADA CONSTANTIN BOSIANU NR. 17, BLOC CORP A, Decizie de impunere 314721 05.03.2021 ETAJ 1, APT. 2A, MUNICIPIUL BUCURESTI, SECTORUL 4, SUB. 1 34523 COVACI CIPRIAN ANDREI STRADA CONSTANTIN BOSIANU NR. 17, BLOC CORP A, Decizie de impunere 298736 05.03.2021 ETAJ 1, APT. 2A, MUNICIPIUL BUCURESTI, SECTORUL 4, SUB. 1 34524 ENE ADRIAN-ALEXANDRU STRADA VULTURENI NR. 78, MUNICIPIUL BUCURESTI, Decizie de impunere 375182 05.03.2021 SECTORUL 4, SUB. 10 34525 LEVCHENKO IULIIA SOSEAUA GIURGIULUI NR. 67-77, BLOC E, SCARA 3, APT. Decizie de impunere 298024 05.03.2021 87, MUNICIPIUL BUCURESTI, SECTORUL 4, SUB. -

Lista Clinici Retea Regina Maria - Beneficiul Optional Preventie

Lista clinici retea Regina Maria - Beneficiul optional Preventie Nume locatie Adresa Telefon Email Oras Centrul Medical Clinimed Str. Bethleen Gabor Nr. 2, partener Regina Maria 0258 863 155 www.clinimed.ro Aiud Centrul Medical Clinimed B-dul. Revolutiei, Nr. 18, partener Regina Maria 0258 833 296 www.clinimed.ro Alba Iulia Centrul Medical Clinimed Str. Marasti, Nr. 22, partener Regina Maria 0258 811 603 www.clinimed.ro Alba Iulia Medisol Calea Motilor, Nr. 107, partener Regina Maria 0358 105 936 www.medisol.ro Alba Iulia Medisol Str. Ariesului, Nr. 66, Bloc 256, Ap. 3, partener Regina Maria 0358 104 546 www.medisol.ro Alba Iulia Terra Aster Str. Motilor, nr. 17A, partener Regina Maria 0258 814 312 www.terraaster.ro Alba Iulia Terra Aster Str. Revolutiei, Nr. 23A, partener Regina Maria 0258 833 408 www.terraaster.ro Alba Iulia Nicomed Str. Dunarii, bl. G103, Sc.A, ap.4 0247 317 664 www.nicomed-alexandria.ro Alexandria Smart Medical Str. Dunarii, nr. 222, partener Regina Maria 0247 310 953 www.smartmedic.ro Alexandria Hiperdia Calea Aurel Vlaicu 138 -140, partener Regina Maria 0257 348 929 www.hiperdia.ro Arad Infomedica Calea Aurel Vlaicu 138 -140 0257 229 000 Arad Policlinica Laser System Str. Andrei Saguna, nr. 14, partener Regina Maria 0257 213 211 www.lasersystem.ro Arad Policlinica Laser System Str. Spitalului, bloc 1A, sc. A, partener Regina Maria 0257 254 337 www.lasersystem.ro Arad Asioptic Str.9 mai, nr 36, partener Regina Maria 0234 537 537 www.asioptic.ro Bacau Jersey Transilvania Str. G. Cosbuc Nr.5, partener Regina Maria 0262 217 203 www.jersey-transilvania.ro Baia Mare Jersey Transilvania Str. -

People's Advocate

European Network of Ombudsmen THE 2014 REPORT OF PEOPLE’S ADVOCATE INSTITUTION - SUMMARY - In accordance with the provisions of art. 60 of the Constitution and those of art. 5 of Law no. 35/1997 on the organization and functioning of the People's Advocate Institution, republished, with subsequent amendments, the Annual Report concerning the activity of the institution for one calendar year is submitted by the People's Advocate, until the 1st of February of the following year, to Parliament for its debate in the joint sitting of the two Chambers. We present below a summary of the 2014 Report of the People’s Advocate Institution, which has been submitted to Parliament, within the legal deadline provided by Law no. 35/1997. GENERAL VOLUME OF ACTIVITY The overview of the activity in 2014 can be summarized in the following statistics: - 16,841 audiences , in which violations of individuals' rights have been alleged, out of which 2,033 at the headquarters and 14,808 at the territorial offices; - 10,346 complaints registered at the People's Advocate Institution, out of which 6,932 at the headquarters and 3,414 at the territorial offices; Of these, a total of 7,703 complaints were sent to the People's Advocate on paper, 2,551 by email, and 92 were received from abroad. - 8,194 calls recorded by the dispatcher service, out of which 2,504 at the headquarters and 5,690 at the territorial offices; - 137 investigations conducted by the People's Advocate Institution, out of which 33 at the headquarters and 104 at the regional offices; - 56 ex officio -

Halele Carol, Bucharest Observatory Case

8. Halele Carol (Bucharest, Romania) This project has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under grant agreement No 776766 Space for Logos H2020 PROJECT Grant Agreement No 776766 Organizing, Promoting and Enabling Heritage Re- Project Full Title use through Inclusion, Technology, Access, Governance and Empowerment Project Acronym OpenHeritage Grant Agreement No. 776766 Coordinator Metropolitan Research Institute (MRI) Project duration June 2018 – May 2021 (48 months) Project website www.openheritage.eu Work Package No. 2 Deliverable D2.2 Individual report on the Observatory Cases Delivery Date 30.11.2019 Author(s) Alina, Tomescu (Eurodite) Joep, de Roo; Meta, van Drunen; Cristiana, Stoian; Contributor(s) (Eurodite); Constantin, Goagea (Zeppelin); Reviewer(s) (if applicable) Public (PU) X Dissemination level: Confidential, only for members of the consortium (CO) This document has been prepared in the framework of the European project OpenHeritage – Organizing, Promoting and Enabling Heritage Re-use through Inclusion, Technology, Access, Governance and Empowerment. This project has received funding from the European Union's Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under grant agreement No 776766. The sole responsibility for the content of this document lies with the authors. It does not necessarily represent the opinion of the European Union. Neither the EASME nor the European Commission is responsible for any use that may be made of the information contained therein. Deliverable -

1 UNIVERSITY of ARTS in BELGRADE Interdisciplinary

UNIVERSITY OF ARTS IN BELGRADE Interdisciplinary postgraduate studies Cultural management and cultural policy Master thesis Reinventing the City: Outlook on Bucharest's Cultural Policy By: Bianca Floarea Supervisor: Milena Dragićević-Šešić, PhD Belgrade, October 2007 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgements………………………………………………………………………… ..………. 3 Abstract……………. …………………………..………………….…………………………..……... 4 Introduction.…………………………………….………………………………………………...…... 5 Methodological Approach. Research Design and Data Analysis….………………………..…….. 7 I. The Evolution of Urban Cultural Policies in Europe..……………………….…............................. 9 I.1. Cultural Policies and the City…………………………………………….…… 9 I.2. Historical Trajectory of Urban Cultural Policies……………………………… 11 II. The Cultural Policy of Bucharest. Analysis and Diagnosis of the City Government’s Approach to Culture……………………………………………………………………………………………... 26 II.1. The City: History, Demographics, Economical Indicators, Architecture and the Arts... 26 II.1.1. History……………………………………………………………………… 27 II.1.2. Demographics………………………………………………………….…… 29 II.1.3. Economical Indicators……………………………………………………… 30 II.1.4. Architecture………………………………………………………………… 30 II.1.5. The Arts Scene…………………………………..…………………………. 32 II. 2. The Local Government: History, Functioning and Structure. Overview of the Cultural Administration………………………………………………………………. 34 II.2.1. The Local Government: History, Functioning And Structure…….……..… 34 II.2.2. Overview of the Cultural Administration…………………..……………… 37 II.3 The Official Approach to Culture -

Download This PDF File

THE SOCIO-SPATIAL DIMENSION OF THE BUCHAREST GHETTOS Viorel MIONEL Silviu NEGUŢ Viorel MIONEL Assistant Professor, Department of Economics History and Geography, Faculty of International Business and Economics, Academy of Economic Studies, Bucharest, Romania Tel.: 0040-213-191.900 Email: [email protected] Abstract Based on a socio-spatial analysis, this paper aims at drawing the authorities’ attention on a few Bucharest ghettos that occurred after the 1990s. Silviu NEGUŢ After the Revolution, Bucharest has undergone Professor, Department of Economics History and Geography, many socio-spatial changes. The modifications Faculty of International Business and Economics, Academy of that occurred in the urban perimeter manifested Economic Studies Bucharest, Romania in the technical and urban dynamics, in the urban Tel.: 0040-213-191.900 infrastructure, and in the socio-economic field. The Email: [email protected] dynamics and the urban evolution of Bucharest have affected the community life, especially the community homogeneity intensely desired during the communist regime by the occurrence of socially marginalized spaces or ghettos as their own inhabitants call them. Ghettos represent an urban stain of color, a special morphologic framework. The Bucharest “ghettos” appeared by a spatial concentration of Roma population and of poverty in zones with a precarious infrastructure. The inhabitants of these areas (Zăbrăuţi, Aleea Livezilor, Iacob Andrei, Amurgului and Valea Cascadelor) are somehow constrained to live in such spaces, mainly because of lack of income, education and because of their low professional qualification. These weak points or handicaps exclude the ghetto population from social participation and from getting access to urban zones with good habitations. -

Informare Consumatori Rechemare Produs

Data : 04/06/2021 Afișare pâna la data : 22/06/2021 INFORMARE CONSUMATORI RECHEMARE PRODUS Vă informăm că societatea THE FAMILY BUTCHERS ROMÂNIA SRL, a inițiat retragerea de la comercializare a produsului MARTINEL MORTADELLA 90 G, ca măsură de prevenție, urmare unei defecțiuni la o linie de feliere și ambalare, ce nu exclude posibilitatea ca pe suprafața unor produse să existe urme minime de praf de metal. CARREFOUR ROMÂNIA S.A. retrage de pe piață și recheamă de la consumatori următorul produs cu datele de identificare de mai jos. Datele de identificare ale produsului sunt: Denumire produs: MARTINEL MORTADELLA 90 G Furnizor: THE FAMILY BUTCHERS ROMÂNIA SRL Cod EAN: 4006229013551 Lot/DLC: 4478815 / 22.06.21 Se recomandă persoanelor care dețin produse din lotul descris mai sus să nu le consume, ci să le distrugă sau să le aducă înapoi în magazinele de unde le-au cumpărat. Contravaloarea produselor va fi returnată, fără a fi necesară prezentarea bonului fiscal. Pentru informații suplimentare, puteți contacta Carrefour România S.A.: [email protected] Magazin Adresa 017 H PITESTI (094) DN 65B KM 6 + 0.72 LOC. BRADU, JUD. ARGES 130 S PASCANI (173) STR. 1 DECEMBRIE 1918, NR. 62-64 PASCANI, JUD. IASI 080 H SFANTU GHEORGHE(102) STRADA LUNCA OLTULUI , NR. 13 179 S DELFINULUI (709) SOS PANTELIMON,NR 249 BLOC 48 PARTER, BUCURESTI 045 CLB SLAT.CORNIS (120) STR. CORNISEI NR. 11C, JUD OLT 083 S GALATI 11 (079) ALEEA GORUNULUI, NR. 6C COMPLEX COMERCIAL, JUD GALATI 081 S CRAIOVA 9 (137) STR. G-RAL MAGHERU, NR. 130, CRAIOVA, JUD. -

Planul Integrat De Dezvoltare Urbana (Pidu)

Bucharest Central Area Integrated Urban Development Plan 1. Recovering the urban identity for the Central area. Today, for many inhabitants, the historic center means only the Lipscani area, which is a simplification of history. We are trying to revitalize and reconnect the different areas which constitute the center of Bucharest, from Victory Square to Carol Park, having the quality of urban life for city residents as a priority and trying to create a city brand for tourists and investors. 2. Recovering the central area located south of the Dambovita river. Almost a quarter of surveyed Bucharest residents had not heard of areas like Antim or Uranus, a result of the brutal urban interventions of the 1980s when, after intense demolitions, fragments of the old town have become enclaves hidden behind the high- rise communist buildings. Bridges over Dambovita disappeared, and whole areas south of the river are now lifeless. We want to reconnect the torn urban tissue and redefine the area located south of Dambovita. recover this part of town by building pedestrian bridges over the river and reconstituting the old ways of Rahovei and Uranus streets as a pedestrian and bicycle priority route. 3. Model of sustainable alternative transportation. Traffic is a major problem for the Bucharest city center. The center should not be a transit area through Bucharest and by encouraging the development of rings and the outside belt, car traffic in the downtown area can easily decrease. We should prioritize alternative forms of transportation - for decades used on a regular basis by most European cities: improve transportation connections and establish a network of streets with priority for cyclists and pedestrians to cross the Center. -

Rahova – Uranus: Un „Cartier Dormitor”?

RAHOVA – URANUS: UN „CARTIER DORMITOR”? BOGDAN VOICU DANA CORNELIA NIŢULESCU ahova–Uranus este o zonă a oraşului Bucureşti situată aproape de centru, însă, ca multe alte cartiere, lipsită aproape complet de orice R viaţă culturală. Studiul de faţă se referă la reprezentările tinerilor din zonă asupra cartierului lor. Folosind date calitative, arătăm că tinerii bucureşteni din Rahova văd în mizerie, aglomeraţie, trafic principalele probleme ale oraşului şi ale zonei în care trăiesc. Investigarea reprezentărilor şi comportamentelor de consum cultural ale tinerilor din cartierul bucureştean Rahova–Uranus relevă caracteristica zonei de a fi, în principal, un „cartier-dormitor”. Oamenii par a veni aici doar ca să locuiască, fiind preocupaţi mai ales în a dormi, a mânca, şi a-şi îndeplini nevoile fiziologice. Materialul de faţă utilizează rezultatele unei cercetări despre modul în care tinerii din zona Rahova – Uranus îşi satisfac nevoia de cultură. Cercetarea, iniţiată şi finanţată de British Council, parte a unui proiect mai larg gestionat de Centrul Internaţional pentru Artă Contemporană1, a fost realizată în octombrie 2006, implicând interviuri semistructurate, cu 26 de tineri între 17 şi 35 de ani. În articolul de faţă ne propunem să contribuim la o mai bună cunoaştere a locuitorilor tineri din zona Rahova – Uranus, identificând nevoile lor de natură culturală, precum şi comportamentele de consum cultural. Ne propunem o descriere, o prezentare de tip documentar a realităţilor observate, explicaţiei şi interpretării fiindu-le alocat un spaţiu mai restrâns. Studiul are în centrul său culturalul nevoia de frumos, cu alte cuvinte acea versiune a culturii în sensul dat de ştiinţele umane2. Suntem interesaţi în ce măsură 1 Mulţumim British Council şi CIAC pentru acceptul de a publica acest material, care utilizează în bună măsură textul raportului de cercetare realizat.