The Four Troublemakers in Danish Orthography

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

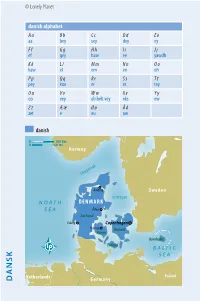

Danish Alphabet DENMARK Danish © Lonely Planet

© Lonely Planet danish alphabet A a B b C c D d E e aa bey sey dey ey F f G g H h I i J j ef gey haw ee yawdh K k L l M m N n O o kaw el em en oh P p Q q R r S s T t pey koo er es tey U u V v W w X x Y y oo vey do·belt vey eks ew Z z Æ æ Ø ø Å å zet e eu aw danish 0 100 km 0 60 mi Norway Skagerrak Aalborg Sweden Kattegat NORTH DENMARK SEA Århus Jutland Esberg Copenhagen Odense Zealand Funen Bornholm Lolland BALTIC SEA Poland Netherlands Germany DANSK DANSK DANISH dansk introduction What do the fairy tales of Hans Christian Andersen and the existentialist philosophy of Søren Kierkegaard have in common (apart from pondering the complexities of life and human character)? Danish (dansk dansk), of course – the language of the oldest European monarchy. Danish contributed to the English of today as a result of the Vi- king conquests of the British Isles in the form of numerous personal and place names, as well as many basic words. As a member of the Scandinavian or North Germanic language family, Danish is closely related to Swedish and Norwegian. It’s particularly close to one of the two official written forms of Norwegian, Bokmål – Danish was the ruling language in Norway between the 15th and 19th centuries, and was the base of this modern Norwegian literary language. In pronunciation, however, Danish differs considerably from both of its neighbours thanks to its softened consonants and often ‘swallowed’ sounds. -

Using 'North Wind and the Sun' Texts to Sample Phoneme Inventories

Blowing in the wind: Using ‘North Wind and the Sun’ texts to sample phoneme inventories Louise Baird ARC Centre of Excellence for the Dynamics of Language, The Australian National University [email protected] Nicholas Evans ARC Centre of Excellence for the Dynamics of Language, The Australian National University [email protected] Simon J. Greenhill ARC Centre of Excellence for the Dynamics of Language, The Australian National University & Department of Linguistic and Cultural Evolution, Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History [email protected] Language documentation faces a persistent and pervasive problem: How much material is enough to represent a language fully? How much text would we need to sample the full phoneme inventory of a language? In the phonetic/phonemic domain, what proportion of the phoneme inventory can we expect to sample in a text of a given length? Answering these questions in a quantifiable way is tricky, but asking them is necessary. The cumulative col- lection of Illustrative Texts published in the Illustration series in this journal over more than four decades (mostly renditions of the ‘North Wind and the Sun’) gives us an ideal dataset for pursuing these questions. Here we investigate a tractable subset of the above questions, namely: What proportion of a language’s phoneme inventory do these texts enable us to recover, in the minimal sense of having at least one allophone of each phoneme? We find that, even with this low bar, only three languages (Modern Greek, Shipibo and the Treger dialect of Breton) attest all phonemes in these texts. -

Germanic Standardizations: Past to Present (Impact: Studies in Language and Society)

<DOCINFO AUTHOR ""TITLE "Germanic Standardizations: Past to Present"SUBJECT "Impact 18"KEYWORDS ""SIZE HEIGHT "220"WIDTH "150"VOFFSET "4"> Germanic Standardizations Impact: Studies in language and society impact publishes monographs, collective volumes, and text books on topics in sociolinguistics. The scope of the series is broad, with special emphasis on areas such as language planning and language policies; language conflict and language death; language standards and language change; dialectology; diglossia; discourse studies; language and social identity (gender, ethnicity, class, ideology); and history and methods of sociolinguistics. General Editor Associate Editor Annick De Houwer Elizabeth Lanza University of Antwerp University of Oslo Advisory Board Ulrich Ammon William Labov Gerhard Mercator University University of Pennsylvania Jan Blommaert Joseph Lo Bianco Ghent University The Australian National University Paul Drew Peter Nelde University of York Catholic University Brussels Anna Escobar Dennis Preston University of Illinois at Urbana Michigan State University Guus Extra Jeanine Treffers-Daller Tilburg University University of the West of England Margarita Hidalgo Vic Webb San Diego State University University of Pretoria Richard A. Hudson University College London Volume 18 Germanic Standardizations: Past to Present Edited by Ana Deumert and Wim Vandenbussche Germanic Standardizations Past to Present Edited by Ana Deumert Monash University Wim Vandenbussche Vrije Universiteit Brussel/FWO-Vlaanderen John Benjamins Publishing Company Amsterdam/Philadelphia TM The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements 8 of American National Standard for Information Sciences – Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ansi z39.48-1984. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Germanic standardizations : past to present / edited by Ana Deumert, Wim Vandenbussche. -

CEMENT for BUILDING with AMBITION Aalborg Portland A/S Portland Aalborg Cover Photo: the Great Belt Bridge, Denmark

CEMENT FOR BUILDING WITH AMBITION Aalborg Portland A/S Cover photo: The Great Belt Bridge, Denmark. AALBORG Aalborg Portland Holding is owned by the Cementir Group, an inter- national supplier of cement and concrete. The Cementir Group’s PORTLAND head office is placed in Rome and the Group is listed on the Italian ONE OF THE LARGEST Stock Exchange in Milan. CEMENT PRODUCERS IN Cementir's global organization is THE NORDIC REGION divided into geographical regions, and Aalborg Portland A/S is included in the Nordic & Baltic region covering Aalborg Portland A/S has been a central pillar of the Northern Europe. business community in Denmark – and particularly North Jutland – for more than 125 years, with www.cementirholding.it major importance for employment, exports and development of industrial knowhow. Aalborg Portland is one of the largest producers of grey cement in the Nordic region and the world’s leading manufacturer of white cement. The company is at the forefront of energy-efficient production of high-quality cement at the plant in Aalborg. In addition to the factory in Aalborg, Aalborg Portland includes five sales subsidiaries in Iceland, Poland, France, Belgium and Russia. Aalborg Portland is part of Aalborg Portland Holding, which is the parent company of a number of cement and concrete companies in i.a. the Nordic countries, Belgium, USA, Turkey, Egypt, Malaysia and China. Additionally, the Group has acti vities within extraction and sales of aggregates (granite and gravel) and recycling of waste products. Read more on www.aalborgportlandholding.com, www.aalborgportland.dk and www.aalborgwhite.com. Data in this brochure is based on figures from 2017, unless otherwise stated. -

Coastal Living in Denmark

To change the color of the coloured box, right-click here and select Format Background, change the color as shown in the picture on the right. Coastal living in Denmark © Daniel Overbeck - VisitNordsjælland To change the color of the coloured box, right-click here and select Format Background, change the color as shown in the picture on the right. The land of endless beaches In Denmark, we look for a touch of magic in the ordinary, and we know that travel is more than ticking sights off a list. It’s about finding wonder in the things you see and the places you go. One of the wonders that we at VisitDenmark are particularly proud of is our nature. Denmark has wonderful beaches open to everyone, and nowhere in the nation are you ever more than 50km from the coast. s. 2 © Jill Christina Hansen To change the color of the coloured box, right-click here and select Format Background, change the color as shown in the picture on the right. Denmark and its regions Geography Travel distances Aalborg • The smallest of the Scandinavian • Copenhagen to Odense: Bornholm countries Under 2 hours by car • The southernmost of the • Odense to Aarhus: Under 2 Scandinavian countries hours by car • Only has a physical border with • Aarhus to Aalborg: Under 2 Germany hours by car • Denmark’s regions are: North, Mid, Jutland West and South Jutland, Funen, Aarhus Zealand, and North Zealand and Copenhagen Billund Facts Copenhagen • Video Introduction • Denmark’s currency is the Danish Kroner Odense • Tipping is not required Zealand • Most Danes speak fluent English Funen • Denmark is of the happiest countries in the world and Copenhagen is one of the world’s most liveable cities • Denmark is home of ‘Hygge’, New Nordic Cuisine, and LEGO® • Denmark is easily combined with other Nordic countries • Denmark is a safe country • Denmark is perfect for all types of travelers (family, romantic, nature, bicyclist dream, history/Vikings/Royalty) • Denmark has a population of 5.7 million people s. -

Mental Health and Safety at Aalborg University, Denmark

Mental health and safety at Aalborg University, Denmark In Denmark, your health issues should usually be directed towards your GP. In special cases like assault or sexual assault, you should contact the police who will assist you to medical treatment. Outside your GP’s opening hours, you can contact the on-call GP, whose phone number will be provided upon calling your GP, or you can find it on www.lægevagten.dk In case of acute emergency, call 112. In our Survival Guide, attached above, you can find additional information regarding health and safety on pages 21-24. Local Police Department Information Campus Aalborg Nordjyllands Politi (The Northern Jutland Police Department). Tel: +45 96301448. In case of emergency: 114. Address: Jyllandsgade 27, 9000 Aalborg Campus Esbjerg Syd- og Sønderjyllands Politi Kirkegade 76 6700 Esbjerg Tel:+45 76111448 Campus Copenhagen Københavns Politi Polititorvet 14 1567 København V Tel:+45 3314 1448 Dean of Students Information We do not have deans of students. If students experience abusive behavior or witness it, they can turn to the university's central student guidance: AAU STUDENT GUIDANCE: Phone: +45 99 40 94 40 (Monday-Friday from 12-15) Mail: [email protected] https://www.en.aau.dk/education/student-guidance/guidance/personal-issues/ https://www.en.aau.dk/education/student-guidance/guidance/offensive-behaviour/ Students are also encouraged to contact an employee in their educational environment if they are more comfortable with that. All employees who receive inquiries about abusive behavior from students must ensure that the case is handled properly. Advice and help on how to handle specific cases can be obtained by contacting the central student guidance on the above contact information. -

From Semantics to Dialectometry

Contents Preface ix Subjunctions as discourse markers? Stancetaking on the topic ‘insubordi- nate subordination’ Werner Abraham Two-layer networks, non-linear separation, and human learning R. Harald Baayen & Peter Hendrix John’s car repaired. Variation in the position of past participles in the ver- bal cluster in Duth Sjef Barbiers, Hans Bennis & Lote Dros-Hendriks Perception of word stress Leonor van der Bij, Dicky Gilbers & Wolfgang Kehrein Empirical evidence for discourse markers at the lexical level Jelke Bloem Verb phrase ellipsis and sloppy identity: a corpus-based investigation Johan Bos 7 7 Om-omission Gosse Bouma 8 Neural semantics Harm Brouwer, Mathew W. Crocker & Noortje J. Venhuizen 7 9 Liberating Dialectology J. K. Chambers 8 0 A new library for construction of automata Jan Daciuk 9 Generating English paraphrases from logic Dan Flickinger 99 Contents Use and possible improvement of UNESCO’s Atlas of the World’s Lan- guages in Danger Tjeerd de Graaf 09 Assessing smoothing parameters in dialectometry Jack Grieve 9 Finding dialect areas by means of bootstrap clustering Wilbert Heeringa 7 An acoustic analysis of English vowels produced by speakers of seven dif- ferent native-language bakgrounds Vincent J. van Heuven & Charlote S. Gooskens 7 Impersonal passives in German: some corpus evidence Erhard Hinrichs 9 7 In Hülle und Fülle – quantiication at a distance in German, Duth and English Jack Hoeksema 9 8 he interpretation of Duth direct speeh reports by Frisian-Duth bilin- guals Franziska Köder, J. W. van der Meer & Jennifer Spenader 7 9 Mining for parsing failures Daniël de Kok & Gertjan van Noord 8 0 Looking for meaning in names Stasinos Konstantopoulos 9 Second thoughts about the Chomskyan revolution Jan Koster 99 Good maps William A. -

• Size • Location • Capital • Geography

Denmark - Officially- Kingdom of Denmark - In Danish- Kongeriget Danmark Size Denmark is approximately 43,069 square kilometers or 16,629 square miles. Denmark consists of a peninsula, Jutland, that extends from Germany northward as well as around 406 islands surrounding the mainland. Some of the larger islands are Fyn, Lolland, Sjælland, Falster, Langeland, MØn, and Bornholm. Its size is comparable to the states of Massachusetts and Connecticut combined. Location Denmark’s exact location is the 56°14’ N. latitude and 8°30’ E. longitude at a central point. It is mostly bordered by water and is considered to be the central point of sea going trade between eastern and western Europe. If standing on the Jutland peninsula and headed in the specific direction these are the bodies of water or countries that would be met. North: Skagettak, Norway West: North Sea, United Kingdom South: Germany East: Kattegat, Sweden Most of the islands governed by Denmark are close in proximity except Bornholm. This island is located in the Baltic Sea south of Sweden and north of Poland. Capital The capital city of Denmark is Copenhagan. In Danish it is Københaun. It is located on the Island of Sjælland. Latitude of the capital is 55°43’ N. and longitude is 12°27’ E. Geography Terrain: Denmark is basically flat land that averages around 30 meters, 100 feet, above sea level. Its highest elevation is Yding SkovhØj that is 173 meters, 586 feet, above sea level. This point is located in the central range of the Jutland peninsula. Page 1 of 8 Coastline: The 406 islands that make up part of Denmark allow for a great amount of coastline. -

Online Activation of L1 Danish Orthography Enhances Spoken Word Recognition of Swedish

Nordic Journal of Linguistics (2021), page 1 of 19 doi:10.1017/S0332586521000056 ARTICLE Online activation of L1 Danish orthography enhances spoken word recognition of Swedish Anja Schüppert1 , Johannes C. Ziegler2, Holger Juul3 and Charlotte Gooskens1 1Center for Language and Cognition Groningen, University of Groningen, P.O. Box 716, 9700 AS Groningen, The Netherlands; Email: [email protected], [email protected] 2Laboratoire de Psychologie Cognitive/CNRS, Aix-Marseille University, 3, place Victor Hugo, 13003 Marseille, France; Email: [email protected] 3Department of Nordic Studies and Linguistics, University of Copenhagen, Emil Holms Kanal 2, 2300 Copenhagen S, Denmark; Email: [email protected] (Received 6 June 2020; revised 9 March 2021; accepted 9 March 2021) Abstract It has been reported that speakers of Danish understand more Swedish than vice versa. One reason for this asymmetry might be that spoken Swedish is closer to written Danish than vice versa. We hypothesise that literate speakers of Danish use their ortho- graphic knowledge of Danish to decode spoken Swedish. To test this hypothesis, first- language (L1) Danish speakers were confronted with spoken Swedish in a translation task. Event-related brain potentials (ERPs) were elicited to study the online brain responses dur- ing decoding operations. Results showed that ERPs to words whose Swedish pronunciation was inconsistent with the Danish spelling were significantly more negative-going than ERPs to words whose Swedish pronunciation was consistent with the Danish spelling between 750 ms and 900 ms after stimulus onset. Together with higher word-recognition scores for consistent items, our data provide strong evidence that online activation of L1 orthography enhances word recognition of spoken Swedish in literate speakers of Danish. -

Population Genomics of the Viking World

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/703405; this version posted July 17, 2019. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 International license. 1 Population genomics of the Viking world 2 3 Ashot Margaryan1,2,3*, Daniel Lawson4*, Martin Sikora1*, Fernando Racimo1*, Simon Rasmussen5, Ida 4 Moltke6, Lara Cassidy7, Emil Jørsboe6, Andrés Ingason1,58,59, Mikkel Pedersen1, Thorfinn 5 Korneliussen1, Helene Wilhelmson8,9, Magdalena Buś10, Peter de Barros Damgaard1, Rui 6 Martiniano11, Gabriel Renaud1, Claude Bhérer12, J. Víctor Moreno-Mayar1,13, Anna Fotakis3, Marie 7 Allen10, Martyna Molak14, Enrico Cappellini3, Gabriele Scorrano3, Alexandra Buzhilova15, Allison 8 Fox16, Anders Albrechtsen6, Berit Schütz17, Birgitte Skar18, Caroline Arcini19, Ceri Falys20, Charlotte 9 Hedenstierna Jonson21, Dariusz Błaszczyk22, Denis Pezhemsky15, Gordon Turner-Walker23, Hildur 10 Gestsdóttir24, Inge Lundstrøm3, Ingrid Gustin8, Ingrid Mainland25, Inna Potekhina26, Italo Muntoni27, 11 Jade Cheng1, Jesper Stenderup1, Jilong Ma1, Julie Gibson25, Jüri Peets28, Jörgen Gustafsson29, Katrine 12 Iversen5,64, Linzi Simpson30, Lisa Strand18, Louise Loe31,32, Maeve Sikora33, Marek Florek34, Maria 13 Vretemark35, Mark Redknap36, Monika Bajka37, Tamara Pushkina15, Morten Søvsø38, Natalia 14 Grigoreva39, Tom Christensen40, Ole Kastholm41, Otto Uldum42, Pasquale Favia43, Per Holck44, Raili -

Introduction to the New Edition of Niels Ege's 1993 Translation Of

Introduction to the New Edition of Niels Ege’s 1993 Translation of Rasmus Rask’s Prize Essay of 1818 Frans Gregersen To cite this version: Frans Gregersen. Introduction to the New Edition of Niels Ege’s 1993 Translation of Rasmus Rask’s Prize Essay of 1818. 2013. hprints-00786171 HAL Id: hprints-00786171 https://hal-hprints.archives-ouvertes.fr/hprints-00786171 Preprint submitted on 7 Feb 2013 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Introduction to the New Edition of Niels Ege’s 1993 Translation of Rasmus Rask’s Prize Essay of 1818* 1. Introduction This edition constitutes a photographic reprint of the English edition of Rasmus Rask‘s prize essay of 1818 which appeared as volume XXVI in the Travaux du Cercle Linguistique de Copenhague in 1993. The only difference, besides the new front matter, is the present introduction, which serves to introduce the author Rasmus Rask, the man and his career, and to contextualize his famous work. It also serves to introduce the translation and the translator, Niels Ege (1927–2003). The prize essay was published in Danish in 1818. In contrast to other works by Rask, notably his introduction to the study of Icelandic (on which, see further below), it was never reissued until Louis Hjelmslev (1899–1965) published a corrected version in Danish as part of his edition of Rask‘s selected works (Rask 1932). -

The Meaning of Language

The Meaning of Language The Meaning of Language Edited by Hans Götzsche The Meaning of Language Edited by Hans Götzsche This book first published 2018 Cambridge Scholars Publishing Lady Stephenson Library, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2PA, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2018 by Hans Götzsche and contributors All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-5275-0542-1 ISBN (13): 978-1-5275-0542-1 TABLE OF CONTENTS Preface ...................................................................................................... vii Chapter One ................................................................................................ 1 The Meanings of Life Hans Götzsche Chapter Two ............................................................................................. 17 The Discovery of Danish Phonology and Prosodic Morphology: From the Third University Caretaker Jens P. Høysgaard (1743) to the 19th Century Hans Basbøll Chapter Three ........................................................................................... 46 What Do Languages Refrain from Copying Morphology? On Structural Obstacles to Morphological Borrowing Stig Eliasson Chapter Four ............................................................................................