A. R. M. V. BOSNIA and HERZEGOVINA

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A/HRC/13/39/Add.1 General Assembly

United Nations A/HRC/13/39/Add.1 General Assembly Distr.: General 25 February 2010 English/French/Spanish only Human Rights Council Thirteenth session Agenda item 3 Promotion and protection of all human rights, civil, political, economic, social and cultural rights, including the right to development Report of the Special Rapporteur on torture and other cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment, Manfred Nowak Addendum Summary of information, including individual cases, transmitted to Governments and replies received* * The present document is being circulated in the languages of submission only as it greatly exceeds the page limitations currently imposed by the relevant General Assembly resolutions. GE.10-11514 A/HRC/13/39/Add.1 Contents Paragraphs Page List of abbreviations......................................................................................................................... 5 I. Introduction............................................................................................................. 1–5 6 II. Summary of allegations transmitted and replies received....................................... 1–305 7 Algeria ............................................................................................................ 1 7 Angola ............................................................................................................ 2 7 Argentina ........................................................................................................ 3 8 Australia......................................................................................................... -

On Conversion to Christianity, Issues Concerning Kurds and Post-2009 Election Protestors As Well As Legal Issues and Exit Procedures

2/2013 ENG Iran On Conversion to Christianity, Issues concerning Kurds and Post-2009 Election Protestors as well as Legal Issues and Exit Procedures Joint report from the Danish Immigration Service, the Norwegian LANDINFO and Danish Refugee Council’s fact-finding mission to Tehran, Iran, Ankara, Turkey and London, United Kingdom 9 November to 20 November 2012 and 8 January to 9 January 2013 Copenhagen, February 2013 Danish Refugee Council LANDINFO Danish Immigration Service Borgergade 10, 3rd floor Storgata 33a, PB 8108 Dep. Ryesgade 53 1300 Copenhagen K 0032 Oslo 2100 Copenhagen Ø Phone: 00 45 33 73 50 00 Phone: +47 23 30 94 70 Phone: 00 45 35 36 66 00 Web: www.drc.dk Web: www.landinfo.no Web: www.newtodenmark.dk E-mail:[email protected] E-mail: [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] Overview of Danish fact finding reports published in 2012 and 2013 Update (2) On Entry Procedures At Kurdistan Regional Government Checkpoints (Krg); Residence Procedures In Kurdistan Region Of Iraq (Kri) And Arrival Procedures At Erbil And Suleimaniyah Airports (For Iraqis Travelling From Non-Kri Areas Of Iraq), Joint Report of the Danish Immigration Service/UK Border Agency Fact Finding Mission to Erbil and Dahuk, Kurdistan Region of Iraq (KRI), conducted 11 to 22 November 2011 2012: 1 Security and human rights issues in South-Central Somalia, including Mogadishu, Report from Danish Immigration Service’s fact finding mission to Nairobi, Kenya and Mogadishu, Somalia, 30 January to 19 February 2012 2012: 2 Afghanistan, Country of Origin Information for Use in the -

Prepared Testimony to the United States Senate Foreign Relations

Prepared Testimony to the United States Senate Foreign Relations Subcommittee on Near Eastern and South and Central Asian Affairs May 11, 2011 HUMAN RIGHTS AND DEMOCRATIC REFORM IN IRAN Andrew Apostolou, Freedom House Chairman Casey, Ranking member Risch, Members of the Subcommittee, it is an honour to be invited to address you and to represent Freedom House. Please allow me to thank you and your staff for all your efforts to advance the cause of human rights and democracy in Iran. It is also a great pleasure to be here with Rudi Bakhtiar and Kambiz Hosseini. They are leaders in how we communicate the human rights issue, both to Iran and to the rest of the world. Freedom House is celebrating its 70th anniversary. We were founded on the eve of the United States‟ entry into World War II by Eleanor Roosevelt and Wendell Wilkie to act as an ideological counterweight to the Nazi‟s anti-democratic ideology. The Nazi headquarters in Munich was known as the Braunes Haus, so Roosevelt and Wilkie founded Freedom House in response. The ruins of the Braunes Haus are now a memorial. Freedom House is actively promoting democracy and freedom around the world. The Second World War context of our foundation is relevant to our Iran work. The Iranian state despises liberal democracy, routinely violates human rights norms through its domestic repression, mocks and denies the Holocaust. Given the threat that the Iranian state poses to its own population and to the Middle East, we regard Iran as an institutional priority. In addition to Freedom House‟s well-known analyses on the state of freedom in the world and our advocacy for democracy, we support democratic activists in some of the world‟s most repressive societies, including Iran. -

IRAN COUNTRY of ORIGIN INFORMATION (COI) REPORT COI Service

IRAN COUNTRY OF ORIGIN INFORMATION (COI) REPORT COI Service Date 28 June 2011 IRAN JUNE 2011 Contents Preface Latest News EVENTS IN IRAN FROM 14 MAY TO 21 JUNE Useful news sources for further information REPORTS ON IRAN PUBLISHED OR ACCESSED BETWEEN 14 MAY AND 21 JUNE Paragraphs Background Information 1. GEOGRAPHY ............................................................................................................ 1.01 Maps ...................................................................................................................... 1.04 Iran ..................................................................................................................... 1.04 Tehran ................................................................................................................ 1.05 Calendar ................................................................................................................ 1.06 Public holidays ................................................................................................... 1.07 2. ECONOMY ................................................................................................................ 2.01 3. HISTORY .................................................................................................................. 3.01 Pre 1979: Rule of the Shah .................................................................................. 3.01 From 1979 to 1999: Islamic Revolution to first local government elections ... 3.04 From 2000 to 2008: Parliamentary elections -

The Iran Nuclear Deal: What You Need to Know About the Jcpoa

THE IRAN NUCLEAR DEAL: WHAT YOU NEED TO KNOW ABOUT THE JCPOA wh.gov/iran-deal What You Need to Know: JCPOA Packet The Details of the JCPOA • FAQs: All the Answers on JCPOA • JCPOA Exceeds WINEP Benchmarks • Timely Access to Iran’s Nuclear Program • JCPOA Meeting (and Exceeding) the Lausanne Framework • JCPOA Does Not Simply Delay an Iranian Nuclear Weapon • Tools to Counter Iranian Missile and Arms Activity • Sanctions That Remain In Place Under the JCPOA • Sanctions Relief — Countering Iran’s Regional Activities What They’re Saying About the JCPOA • National Security Experts and Former Officials • Regional Editorials: State by State • What the World is Saying About the JCPOA Letters and Statements of Support • Iran Project Letter • Letter from former Diplomats — including five former Ambassadors to Israel • Over 100 Ambassador letter to POTUS • US Conference of Catholic Bishops Letter • Atlantic Council Iran Task Force Statement Appendix • Statement by the President on Iran • SFRC Hearing Testimony, SEC Kerry July 14, 2015 July 23, 2015 • Key Excerpts of the JCPOA • SFRC Hearing Testimony, SEC Lew July 23, 2015 • Secretary Kerry Press Availability on Nuclear Deal with Iran • SFRC Hearing Testimony, SEC Moniz July 14, 2015 July 23, 2015 • Secretary Kerry and Secretary Moniz • SASC Hearing Testimony, SEC Carter Washington Post op-ed July 29, 2015 July 22, 2015 THE DETAILS OF THE JCPOA After 20 months of intensive negotiations, the U.S. and our international partners have reached an historic deal that will verifiably prevent Iran from obtaining a nuclear weapon. The United States refused to take a bad deal, pressing for a deal that met every single one of our bottom lines. -

Timeline of Iran's Foreign Relations Semira N

Timeline of Iran's Foreign Relations Semira N. Nikou 1979 Feb. 12 – Syria was the first Arab country to recognize the revolutionary regime when President Hafez al Assad sent a telegram of congratulations to Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini. The revolution transformed relations between Iran and Syria, which had often been hostile under the shah. Feb. 14 – Students stormed the U.S. Embassy in Tehran, but were evicted by the deputy foreign minister and Iranian security forces. Feb. 18 – Iran cut diplomatic relations with Israel. Oct. 22 – The shah entered the United States for medical treatment. Iran demanded the shah’s return to Tehran. Nov. 4 – Students belonging to the Students Following the Imam’s Line seized the U.S. Embassy in Tehran. The hostage crisis lasted 444 days. On Nov. 12, Washington cut off oil imports from Iran. On Nov. 14, President Carter issued Executive Order 12170 ordering a freeze on an estimated $6 billion of Iranian assets and official bank deposits in the United States. March – Iran severed formal diplomatic ties with Egypt after it signed a peace deal with Israel. Three decades later, Egypt was still the only Arab country that did not have an embassy in Tehran. 1980 April 7 – The United States cut off diplomatic relations with Iran. April 25 – The United States attempted a rescue mission of the American hostages during Operation Eagle Claw. The mission failed due to a sandstorm and eight American servicemen were killed. Ayatollah Khomeini credited the failure to divine intervention. Sept. 22 – Iraq invaded Iran in a dispute over the Shatt al-Arab waterway. -

Basic Christian 2009 - C Christian Information, Links, Resources and Free Downloads

Sunday, June 14, 2009 16:07 GMT Basic Christian 2009 - C Christian Information, Links, Resources and Free Downloads Copyright © 2004-2008 David Anson Brown http://www.basicchristian.org/ Basic Christian 2009 - Current Active Online PDF - News-Info Feed - Updated Automatically (PDF) Generates a current PDF file of the 2009 Extended Basic Christian info-news feed. http://rss2pdf.com?url=http://www.BasicChristian.org/BasicChristian_Extended.rss Basic Christian 2009 - Extended Version - News-Info Feed (RSS) The a current Extended Basic Christian info-news feed. http://www.BasicChristian.org/BasicChristian_Extended.rss RSS 2 PDF - Create a PDF file complete with links of this current Basic Christian News/Info Feed after the PDF file is created it can then be saved to your computer {There is a red PDF Create Button at the top right corner of the website www.basicChristian.us} Free Online RSS to PDF Generator. http://rss2pdf.com?url=http://www.BasicChristian.org/BasicChristian.rss Updated: 06-12-2009 Basic Christian 2009 (1291 Pages) - The BasicChristian.org Website Articles (PDF) Basic Christian Full Content PDF Version. The BasicChristian.org most complete resource. http://www.basicchristian.info/downloads/BasicChristian.pdf !!! Updated: 2009 Version !!! FREE Download - Basic Christian Complete - eBook Version (.CHM) Possibly the best Basic Christian resource! Download it and give it a try!Includes the Red Letter Edition Holy Bible KJV 1611 Version. To download Right-Click then Select Save Target _As... http://www.basicchristian.info/downloads/BasicChristian.CHM Sunday, June 14, 2009 16:07 GMT / Created by RSS2PDF.com Page 1 of 125 Christian Faith Downloads - A Christian resource center with links to many FREE Mp3 downloads (Mp3's) Christian Faith Downloads - 1st Corinthians 2:5 That your faith should not stand in the wisdom of men, but in the power of God. -

USCIRF's 2021 Annual Report

UNITED STATES COMMISSION ON INTERNATIONAL RELIGIOUS FREEDOM ANNUAL REPORT 2021 WWW.USCIRF.GOV ANNUAL REPORT OF THE U.S. COMMISSION ON INTERNATIONAL RELIGIOUS FREEDOM COMMISSIONERS Gayle Manchin Chair Tony Perkins Anurima Bhargava Vice Chairs Gary L. Bauer James W. Carr Frederick A. Davie Nadine Maenza Johnnie Moore Nury Turkel Erin D. Singshinsuk Executive Director April 2021 PROFESSIONAL STAFF Dwight Bashir, Director of Outreach and Policy Elizabeth K. Cassidy, Director of Research and Policy Roy Haskins, Director of Finance and Operations Thomas Kraemer, Director of Human Resources Danielle Ashbahian, Senior Communications Specialist Kirsten Lavery, Supervisory Policy Analyst Jamie Staley, Senior Congressional Relations Specialist Scott Weiner, Supervisory Policy Analyst Kurt Werthmuller, Supervisory Policy Analyst Keely Bakken, Senior Policy Analyst Mingzhi Chen, Policy Analyst Patrick Greenwalt, Policy Analyst Gabrielle Hasenstab, Communications Specialist Niala Mohammad, Senior Policy Analyst Jason Morton, Senior Policy Analyst Mohyeldin Omer, Policy Analyst Zachary Udin, Researcher Nina Ullom, Congressional Relations Specialist Madeline Vellturo, Policy Analyst U.S. COMMISSION ON INTERNATIONAL RELIGIOUS FREEDOM 732 North Capitol Street, NW, Suite A714 Washington, DC 20401 (P) 202–523–3240 www.uscirf.gov TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction and Overview ..................................................1 About this Report ...........................................................1 Standards for CPC, SWL, and EPC Recommendations ...................................1 -

Lenten Devotions, March 27

Faithful unto Death: The Testimony of Iranian Martyrs Amir Montazami, his wife Fereshteh Dibaj, and their daughter Christine (Photo courtesy, Elam Ministries, 2006) Yesterday I shared the story of Iranian Christian martyr Bishop Haik Hovsepian Mehr. I also mentioned the friend for whom he, a persecuted Christian himself, became an advocate: Mehdi Dibaj. Today I want to tell you more about Pastor Dibaj himself and his legacy. Those of us in the West, who worship in freedom, can hardly imagine what it is like to have one after another of your church leaders disappear and be murdered. But this is what happened in Iran. Christians in Nigeria, Pakistan, India, China, and elsewhere can relate to what the Church in Iran went through and still experiences. When Bishop Haik spoke up for Dibaj, the pastor had already been under death sentence for apostasy in prison for over nine years. As I revealed yesterday, Haik’s public intercession and advocacy for Dibaj resulted in both Dibaj’s release from imminent execution and Haik’s murder. Dibaj was with his family that had waited for him for so long. Then on June 24, he disappeared on his way home from a Christian retreat in Karaj, a little northwest of Tehran. He was expected in time for his daughter Fereshteh’s sixteenth birthday party, but never showed up. Iranian Christians were still reeling from Dibaj’s disappearance when another church leader, the Reverend Tateos Michaelian, was abducted on June 29. Michaelian, senior pastor of St. John Armenian Evangelical Church (Presbyterian Church of Iran), had taken over as president of the Council of Evangelical Ministers when Haik was murdered. -

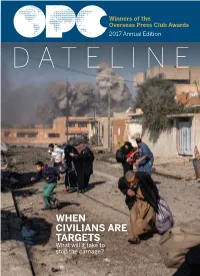

WHEN CIVILIANS ARE TARGETS What Will It Take to Stop the Carnage?

Winners of the Overseas Press Club Awards 2017 Annual Edition DATELINE WHEN CIVILIANS ARE TARGETS What will it take to stop the carnage? DATELINE 2017 1 President’s Letter / dEIdRE dEPkE here is a theme to our gathering tonight at the 78th entries, narrowing them to our 22 winners. Our judging process was annual Overseas Press Club Gala, and it’s not an easy one. ably led by Scott Kraft of the Los Our work as journalists across the globe is under Angeles Times. Sarah Lubman headed our din- unprecedented and frightening attack. Since the conflict in ner committee, setting new records TSyria began in 2011, 107 journalists there have been killed, according the for participation. She was support- Committee to Protect Journalists. That’s more members of the press corps ed by Bill Holstein, past president of the OPC and current head of to die than were lost during 20 years of war in Vietnam. In the past year, the OPC Foundation’s board, and our colleagues also have been fatally targeted in Iraq, Yemen and Ukraine. assisted by her Brunswick colleague Beatriz Garcia. Since 2013, the Islamic State has captured or killed 11 journalists. Almost This outstanding issue of Date- 300 reporters, editors and photographers are being illegally detained by line was edited by Michael Serrill, a past president of the OPC. Vera governments around the world, with at least 81 journalists imprisoned Naughton is the designer (she also in Turkey alone. And at home, we have been labeled the “enemy of the recently updated the OPC logo). -

The Dangers of Ransom Payments to Iran Hearing

FUELING TERROR: THE DANGERS OF RANSOM PAYMENTS TO IRAN HEARING BEFORE THE SUBCOMMITTEE ON OVERSIGHT AND INVESTIGATIONS OF THE COMMITTEE ON FINANCIAL SERVICES U.S. HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES ONE HUNDRED FOURTEENTH CONGRESS SECOND SESSION SEPTEMBER 8, 2016 Printed for the use of the Committee on Financial Services Serial No. 114–100 ( U.S. GOVERNMENT PUBLISHING OFFICE 25–944 PDF WASHINGTON : 2018 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Publishing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512–1800; DC area (202) 512–1800 Fax: (202) 512–2104 Mail: Stop IDCC, Washington, DC 20402–0001 VerDate Nov 24 2008 21:22 Mar 08, 2018 Jkt 025944 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 5011 Sfmt 5011 K:\DOCS\25944.TXT TERI HOUSE COMMITTEE ON FINANCIAL SERVICES JEB HENSARLING, Texas, Chairman PATRICK T. MCHENRY, North Carolina, MAXINE WATERS, California, Ranking Vice Chairman Member PETER T. KING, New York CAROLYN B. MALONEY, New York EDWARD R. ROYCE, California NYDIA M. VELA´ ZQUEZ, New York FRANK D. LUCAS, Oklahoma BRAD SHERMAN, California SCOTT GARRETT, New Jersey GREGORY W. MEEKS, New York RANDY NEUGEBAUER, Texas MICHAEL E. CAPUANO, Massachusetts STEVAN PEARCE, New Mexico RUBE´ N HINOJOSA, Texas BILL POSEY, Florida WM. LACY CLAY, Missouri MICHAEL G. FITZPATRICK, Pennsylvania STEPHEN F. LYNCH, Massachusetts LYNN A. WESTMORELAND, Georgia DAVID SCOTT, Georgia BLAINE LUETKEMEYER, Missouri AL GREEN, Texas BILL HUIZENGA, Michigan EMANUEL CLEAVER, Missouri SEAN P. DUFFY, Wisconsin GWEN MOORE, Wisconsin ROBERT HURT, Virginia KEITH ELLISON, Minnesota STEVE STIVERS, Ohio ED PERLMUTTER, Colorado STEPHEN LEE FINCHER, Tennessee JAMES A. HIMES, Connecticut MARLIN A. STUTZMAN, Indiana JOHN C. -

A Case Study of Iran's Nuclear Deal

A Discourse Analysis of the Conflict Coverage in the Mainstream Media: A Case Study of Iran’s Nuclear Deal Amir Yoosofi Submitted to the Institute of Graduate Studies and Research in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Communication and Media Studies Eastern Mediterranean University July 2016 Gazimağusa, North Cyprus Approval of the Institute of Graduate Studies and Research ______________________ Prof. Dr. Mustafa Tümer Acting Director I certify that this thesis satisfies the requirements as a thesis for the degree of Master of Arts in Communication and Media Studies. ___________________________________________ Assoc. Prof. Dr. Ümit İnatçı Chair, Department of Communication and Media Studies We certify that we have read this thesis and that in our opinion it is fully adequate in scope and quality as a thesis for the degree of Master of Arts in Communication and Media Studies. ______________________________ Assoc. Prof. Dr. Tuğrul İlter Supervisor Examining Committee 1. Assoc. Prof. Dr. Hanife Aliefendioğlu _____________________________ 2. Assoc. Prof. Dr. Tuğrul İlter ____________________________ 3. Asst. Prof. Yetin Arslan _____________________________ ABSTRACT In an attempt to examine the possibility of a constructive communication with a country like Iran, the intention of this thesis is to acquire a diverse perspective toward the current political and cultural struggles in the relationship between the country and the wider world. Studying the very recent Iranian nuclear deal, I am hoping that this study will provide creative alternative perspectives for more constructive conflict coverage in the future. Very often the conflict between Iran and the rest of the world has been reduced to simple binary oppositions such as dictatorship vs.