Details the Plant Kingdom and Hallucinogens (Part III)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

"National List of Vascular Plant Species That Occur in Wetlands: 1996 National Summary."

Intro 1996 National List of Vascular Plant Species That Occur in Wetlands The Fish and Wildlife Service has prepared a National List of Vascular Plant Species That Occur in Wetlands: 1996 National Summary (1996 National List). The 1996 National List is a draft revision of the National List of Plant Species That Occur in Wetlands: 1988 National Summary (Reed 1988) (1988 National List). The 1996 National List is provided to encourage additional public review and comments on the draft regional wetland indicator assignments. The 1996 National List reflects a significant amount of new information that has become available since 1988 on the wetland affinity of vascular plants. This new information has resulted from the extensive use of the 1988 National List in the field by individuals involved in wetland and other resource inventories, wetland identification and delineation, and wetland research. Interim Regional Interagency Review Panel (Regional Panel) changes in indicator status as well as additions and deletions to the 1988 National List were documented in Regional supplements. The National List was originally developed as an appendix to the Classification of Wetlands and Deepwater Habitats of the United States (Cowardin et al.1979) to aid in the consistent application of this classification system for wetlands in the field.. The 1996 National List also was developed to aid in determining the presence of hydrophytic vegetation in the Clean Water Act Section 404 wetland regulatory program and in the implementation of the swampbuster provisions of the Food Security Act. While not required by law or regulation, the Fish and Wildlife Service is making the 1996 National List available for review and comment. -

Appendix Color Plates of Solanales Species

Appendix Color Plates of Solanales Species The first half of the color plates (Plates 1–8) shows a selection of phytochemically prominent solanaceous species, the second half (Plates 9–16) a selection of convol- vulaceous counterparts. The scientific name of the species in bold (for authorities see text and tables) may be followed (in brackets) by a frequently used though invalid synonym and/or a common name if existent. The next information refers to the habitus, origin/natural distribution, and – if applicable – cultivation. If more than one photograph is shown for a certain species there will be explanations for each of them. Finally, section numbers of the phytochemical Chapters 3–8 are given, where the respective species are discussed. The individually combined occurrence of sec- ondary metabolites from different structural classes characterizes every species. However, it has to be remembered that a small number of citations does not neces- sarily indicate a poorer secondary metabolism in a respective species compared with others; this may just be due to less studies being carried out. Solanaceae Plate 1a Anthocercis littorea (yellow tailflower): erect or rarely sprawling shrub (to 3 m); W- and SW-Australia; Sects. 3.1 / 3.4 Plate 1b, c Atropa belladonna (deadly nightshade): erect herbaceous perennial plant (to 1.5 m); Europe to central Asia (naturalized: N-USA; cultivated as a medicinal plant); b fruiting twig; c flowers, unripe (green) and ripe (black) berries; Sects. 3.1 / 3.3.2 / 3.4 / 3.5 / 6.5.2 / 7.5.1 / 7.7.2 / 7.7.4.3 Plate 1d Brugmansia versicolor (angel’s trumpet): shrub or small tree (to 5 m); tropical parts of Ecuador west of the Andes (cultivated as an ornamental in tropical and subtropical regions); Sect. -

Dr. Duke's Phytochemical and Ethnobotanical Databases List of Plants for Tinnitus

Dr. Duke's Phytochemical and Ethnobotanical Databases List of Plants for Tinnitus Plant Chemical Count Activity Count Newcastelia viscida 1 1 Platanus occidentalis 1 1 Tacca aspera 1 1 Avicennia tomentosa 2 1 Coccoloba excoriata 1 1 Diospyros morrisiana 1 1 Cassia siamea 1 1 Diospyros derra 1 1 Rhododendron ledebourii 1 1 Thymelaea hirsuta 1 1 Dichrostachys glomerata 1 1 Diospyros wallichii 2 1 Erythroxylum gracilipes 1 1 Hyptis emoryi 1 1 Lemaireocereus thurberi 1 1 Pongamia pinnata 1 1 Quercus championi 2 1 Rubus spectabilis 2 1 Tetracera scandens 2 1 Arbutus menziesii 1 1 Betula sp. 2 1 Dillenia pentagyna 2 1 Erythroxylum rotundifolium 1 1 Grewia tiliaefolia 1 1 Inga punctata 1 1 Lepechinia hastata 1 1 Paeonia japonica 1 1 Plant Chemical Count Activity Count Pouteria torta 1 1 Rabdosia adenantha 1 1 Selaginella delicatula 1 1 Stemonoporus affinis 2 1 Rosa davurica 1 1 Calophyllum lankaensis 1 1 Colubrina granulosa 1 1 Acrotrema uniflorum 1 1 Diospyros hirsuta 2 1 Pedicularis palustris 1 1 Pistacia major 1 1 Psychotria adenophylla 2 1 Buxus microphylla 2 1 Clinopodium umbrosum 1 1 Diospyros maingayi 2 1 Epilobium rosmarinifolium 1 1 Garcinia xanthochymus 1 1 Hippuris vulgare 1 1 Kleinhovia hospita 1 1 Crotalaria semperflorens 1 1 Diospyros abyssinica 2 1 Isodon grandifolius 1 1 Salvia mexicana 1 1 Shorea affinis 2 1 Diospyros singaporensis 2 1 Erythroxylum amazonicum 1 1 Euclea crispa 1 1 2 Plant Chemical Count Activity Count Givotia rottleriformis 2 1 Zizyphus trinervia 2 1 Simaba obovata 1 1 Betula cordifolia 1 1 Platanus orientalis 1 1 Triadenum japonicum 1 1 Woodfordia floribunda 2 1 Calea zacatechichi 1 1 Diospyros natalensis 1 1 Alyxia buxifolia 1 1 Brassica napus var. -

Chloroform Extracts of Ipomoea Alba and Ipomoea Tricolor Seeds Show Strong In-Vitro Antibacterial, Antifungal, and Cytotoxic Activity SIMS K

Research Horizons Day & Research Week April 6-13, 2018 Chloroform Extracts of Ipomoea alba and Ipomoea tricolor Seeds Show Strong In-vitro Antibacterial, Antifungal, and Cytotoxic Activity SIMS K. LAWSON, MARY N. DAVIS, CAROLYN BRAZELL – Biology Department WILLIAM N. SETZER – Mentor – Chemistry Department Overview Antibiotic and antifungal resistance is a growing concern. Novel anti-tumor compounds are continuously sought after. If a novel phytochemical can be discovered with high specificity for certain types of cancer cells, then this could be an invaluable aid to oncological medicine. Plant-based drugs (phyto-pharmaceuticals) have always made up a considerable portion of our known medicines. The search for these plant medicines often begins with anthropological/ ethnobotanical research, as was the case here. Figure 2. - Ancient Olmec tribes mixed the sap of I. alba with sap from the rubber tree to make their rubber balls extra “bouncy”. Their ancient ball games were played since 1300 B.C.. Often, the losers were sacrificed, and sometimes the ball was made from a human Methods skull wrapped in rubber. Figure 1.- Morning glory (Ipomoea spp.) seeds have long been the subject of folklore, myth, and speculation. Some varieties (I. tricolor and I. Cold extractions of the ground seeds of each Ipomoea violacea) contain lysergic acid derivatives, which are known to be species were made with chloroform. Seven bacteria and hallucinogenic, and are closely related chemically to the famous LSD molecule. The Mayans are known to have used morning glory seeds during three fungi were obtained and cultured for multiple certain religious rituals. generations. Then, minimum inhibitory concentrations Table 1.- Antibacterial (MIC, μg/mL), antifungal (MIC, μg/mL), (MIC’s) of the extracts were determined against the and cytotoxic (IC50, μg/mL) activities of Ipomoea CHCl3 seed bacteria and fungi using broth microdilution (BM) extracts. -

Vacuolar Proton Pumping: More Than the Sum of Its Parts?

Spotlight Vacuolar proton pumping: more than the sum of its parts? Cornelia Eisenach, Ulrike Baetz, and Enrico Martinoia Institute of Plant Biology, University of Zu¨ rich, Zollikerstrasse 107, CH-8008 Zu¨ rich, Switzerland Petunia flower colour is dependent on vacuolar pH and is vacuole of flower petal cells, and the colour of these antho- therefore used to study acidification mechanisms. Re- cyanins is dependent on–among other factors–vacuolar cently, it was shown that the concerted action of two pH. In petunia a shift in vacuolar pH causes a change in tonoplast-localised P3-ATPases is required to hyperaci- flower colour. Mutants that display a flower colour differ- dify vacuoles of petunia petal epidermis cells. Here we ent to the red-flowering wild type are a useful tool to discuss how steep cross-tonoplast pH gradients may be analyse gene function in vacuolar pH maintenance. Over- established in specific cells. all, seven pH-mutants defective in petunia flower colour and pH have been identified and termed ph1 to ph7 [5]. The acidity of plant vacuoles varies between plant species, Within the past decade the team led by Francesca Quat- organs, and cell types. In morning glory (Ipomoea tricolor), trocchio at Amsterdam University has been successful in when the slightly acidic vacuoles of flowers become neutral, identifying several genes that are affected in the respective a shift from a purple to the characteristic blue flower colour mutants, using transposon-tagging strategies. Some of the can be observed. By contrast, petal epidermis cells of genes such as PH3, PH4 and PH6 are transcriptional reg- petunia (Petunia hybrida) contain acidic vacuoles with a ulators. -

Risk Assessment of Argyreia Nervosa

Risk assessment of Argyreia nervosa RIVM letter report 2019-0210 W. Chen | L. de Wit-Bos Risk assessment of Argyreia nervosa RIVM letter report 2019-0210 W. Chen | L. de Wit-Bos RIVM letter report 2019-0210 Colophon © RIVM 2020 Parts of this publication may be reproduced, provided acknowledgement is given to the: National Institute for Public Health and the Environment, and the title and year of publication are cited. DOI 10.21945/RIVM-2019-0210 W. Chen (author), RIVM L. de Wit-Bos (author), RIVM Contact: Lianne de Wit Department of Food Safety (VVH) [email protected] This investigation was performed by order of NVWA, within the framework of 9.4.46 Published by: National Institute for Public Health and the Environment, RIVM P.O. Box1 | 3720 BA Bilthoven The Netherlands www.rivm.nl/en Page 2 of 42 RIVM letter report 2019-0210 Synopsis Risk assessment of Argyreia nervosa In the Netherlands, seeds from the plant Hawaiian Baby Woodrose (Argyreia nervosa) are being sold as a so-called ‘legal high’ in smart shops and by internet retailers. The use of these seeds is unsafe. They can cause hallucinogenic effects, nausea, vomiting, elevated heart rate, elevated blood pressure, (severe) fatigue and lethargy. These health effects can occur even when the seeds are consumed at the recommended dose. This is the conclusion of a risk assessment performed by RIVM. Hawaiian Baby Woodrose seeds are sold as raw seeds or in capsules. The raw seeds can be eaten as such, or after being crushed and dissolved in liquid (generally hot water). -

Monographs on Datura Stramonium L

The School of Pharmaceutical and Biomedical Sciences Pokhara University, P. O. Box 427, Lekhnath, Kaski, NEPAL Monographs on Datura stramonium L Submitted By Bhakta Prasad Gaire Bachelor in Pharmaceutical Sciences (5th Batch) Roll No. 29/2005 [2008] [TYPE THE COMPANY ADDR ESS ] A Plant Monograph on Dhaturo (Datura stramonium L.) Prepared by Bhakta Prasad Gaire Roll No. 29/2005 Submitted to The School of Pharmaceutical and Biomedical Sciences Pokhara University, Dhungepatan-12, Lekhnath, Kaski, NEPAL 2008 ii PREFACE Datura was quite abundantly available in my village (Kuwakot-8, Syangja) since the days of my ancestors. Although it's medicinal uses were not so clear and established at that time, my uncle had a belief that when given along with Gaja, it'll cure diarrhea in cattle. But he was very particular of its use in man and was constantly reminding me not to take it, for it can cause madness. I, on the other hand was very curious and often used to wonder how it looks and what'll actually happen if I take it. This curiosity was also fuelled by other rumours floating around in the village, of the cases of mass hysteria which happened when people took Datura with Panchamrit and Haluwa during Shivaratri and Swasthani Puja. It was in 2052 B.S (I was in class 3 at that time) when an incident happened. One day I came earlier from school (around 2'0 clock), only to find nobody at home. The door was locked and I frantically searched for my mother and sister, but in vain. -

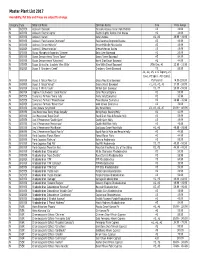

Master Plant List 2017.Xlsx

Master Plant List 2017 Availability, Pot Size and Prices are subject to change. Category Type Botanical Name Common Name Size Price Range N BREVER Azalea X 'Cascade' Cascade Azalea (Glenn Dale Hybrid) #3 49.99 N BREVER Azalea X 'Electric Lights' Electric Lights Double Pink Azalea #2 44.99 N BREVER Azalea X 'Karen' Karen Azalea #2, #3 39.99 - 49.99 N BREVER Azalea X 'Poukhanense Improved' Poukhanense Improved Azalea #3 49.99 N BREVER Azalea X 'Renee Michelle' Renee Michelle Pink Azalea #3 49.99 N BREVER Azalea X 'Stewartstonian' Stewartstonian Azalea #3 49.99 N BREVER Buxus Microphylla Japonica "Gregem' Baby Gem Boxwood #2 29.99 N BREVER Buxus Sempervirens 'Green Tower' Green Tower Boxwood #5 64.99 N BREVER Buxus Sempervirens 'Katerberg' North Star Dwarf Boxwood #2 44.99 N BREVER Buxus Sinica Var. Insularis 'Wee Willie' Wee Willie Dwarf Boxwood Little One, #1 13.99 - 21.99 N BREVER Buxus X 'Cranberry Creek' Cranberry Creek Boxwood #3 89.99 #1, #2, #5, #15 Topiary, #5 Cone, #5 Spiral, #10 Spiral, N BREVER Buxus X 'Green Mountain' Green Mountain Boxwood #5 Pyramid 14.99-299.99 N BREVER Buxus X 'Green Velvet' Green Velvet Boxwood #1, #2, #3, #5 17.99 - 59.99 N BREVER Buxus X 'Winter Gem' Winter Gem Boxwood #5, #7 59.99 - 99.99 N BREVER Daphne X Burkwoodii 'Carol Mackie' Carol Mackie Daphne #2 59.99 N BREVER Euonymus Fortunei 'Ivory Jade' Ivory Jade Euonymus #2 35.99 N BREVER Euonymus Fortunei 'Moonshadow' Moonshadow Euonymus #2 29.99 - 35.99 N BREVER Euonymus Fortunei 'Rosemrtwo' Gold Splash Euonymus #2 39.99 N BREVER Ilex Crenata 'Sky Pencil' -

Dr. Duke's Phytochemical and Ethnobotanical Databases List of Plants for Lyme Disease (Chronic)

Dr. Duke's Phytochemical and Ethnobotanical Databases List of Plants for Lyme Disease (Chronic) Plant Chemical Count Activity Count Garcinia xanthochymus 1 1 Nicotiana rustica 1 1 Acacia modesta 1 1 Galanthus nivalis 1 1 Dryopteris marginalis 2 1 Premna integrifolia 1 1 Senecio alpinus 1 1 Cephalotaxus harringtonii 1 1 Comptonia peregrina 1 1 Diospyros rotundifolia 1 1 Alnus crispa 1 1 Haplophyton cimicidum 1 1 Diospyros undulata 1 1 Roylea elegans 1 1 Bruguiera gymnorrhiza 1 1 Gmelina arborea 1 1 Orthosphenia mexicana 1 1 Lumnitzera racemosa 1 1 Melilotus alba 2 1 Duboisia leichhardtii 1 1 Erythroxylum zambesiacum 1 1 Salvia beckeri 1 1 Cephalotaxus spp 1 1 Taxus cuspidata 3 1 Suaeda maritima 1 1 Rhizophora mucronata 1 1 Streblus asper 1 1 Plant Chemical Count Activity Count Dianthus sp. 1 1 Glechoma hirsuta 1 1 Phyllanthus flexuosus 1 1 Euphorbia broteri 1 1 Hyssopus ferganensis 1 1 Lemaireocereus thurberi 1 1 Holacantha emoryi 1 1 Casearia arborea 1 1 Fagonia cretica 1 1 Cephalotaxus wilsoniana 1 1 Hydnocarpus anthelminticus 2 1 Taxus sp 2 1 Zataria multiflora 1 1 Acinos thymoides 1 1 Ambrosia artemisiifolia 1 1 Rhododendron schotense 1 1 Sweetia panamensis 1 1 Thymelaea hirsuta 1 1 Argyreia nervosa 1 1 Carapa guianensis 1 1 Parthenium hysterophorus 1 1 Rhododendron anthopogon 1 1 Strobilanthes cusia 1 1 Dianthus superbus 1 1 Pyropolyporus fomentarius 1 1 Euphorbia hermentiana 1 1 Porteresia coarctata 1 1 2 Plant Chemical Count Activity Count Aerva lanata 1 1 Rivea corymbosa 1 1 Solanum mammosum 1 1 Juniperus horizontalis 1 1 Maytenus -

A Molecular Phylogeny of the Solanaceae

TAXON 57 (4) • November 2008: 1159–1181 Olmstead & al. • Molecular phylogeny of Solanaceae MOLECULAR PHYLOGENETICS A molecular phylogeny of the Solanaceae Richard G. Olmstead1*, Lynn Bohs2, Hala Abdel Migid1,3, Eugenio Santiago-Valentin1,4, Vicente F. Garcia1,5 & Sarah M. Collier1,6 1 Department of Biology, University of Washington, Seattle, Washington 98195, U.S.A. *olmstead@ u.washington.edu (author for correspondence) 2 Department of Biology, University of Utah, Salt Lake City, Utah 84112, U.S.A. 3 Present address: Botany Department, Faculty of Science, Mansoura University, Mansoura, Egypt 4 Present address: Jardin Botanico de Puerto Rico, Universidad de Puerto Rico, Apartado Postal 364984, San Juan 00936, Puerto Rico 5 Present address: Department of Integrative Biology, 3060 Valley Life Sciences Building, University of California, Berkeley, California 94720, U.S.A. 6 Present address: Department of Plant Breeding and Genetics, Cornell University, Ithaca, New York 14853, U.S.A. A phylogeny of Solanaceae is presented based on the chloroplast DNA regions ndhF and trnLF. With 89 genera and 190 species included, this represents a nearly comprehensive genus-level sampling and provides a framework phylogeny for the entire family that helps integrate many previously-published phylogenetic studies within So- lanaceae. The four genera comprising the family Goetzeaceae and the monotypic families Duckeodendraceae, Nolanaceae, and Sclerophylaceae, often recognized in traditional classifications, are shown to be included in Solanaceae. The current results corroborate previous studies that identify a monophyletic subfamily Solanoideae and the more inclusive “x = 12” clade, which includes Nicotiana and the Australian tribe Anthocercideae. These results also provide greater resolution among lineages within Solanoideae, confirming Jaltomata as sister to Solanum and identifying a clade comprised primarily of tribes Capsiceae (Capsicum and Lycianthes) and Physaleae. -

Gardenergardener®

Theh American A n GARDENERGARDENER® The Magazine of the AAmerican Horticultural Societyy January / February 2016 New Plants for 2016 Broadleaved Evergreens for Small Gardens The Dwarf Tomato Project Grow Your Own Gourmet Mushrooms contents Volume 95, Number 1 . January / February 2016 FEATURES DEPARTMENTS 5 NOTES FROM RIVER FARM 6 MEMBERS’ FORUM 8 NEWS FROM THE AHS 2016 Seed Exchange catalog now available, upcoming travel destinations, registration open for America in Bloom beautifi cation contest, 70th annual Colonial Williamsburg Garden Symposium in April. 11 AHS MEMBERS MAKING A DIFFERENCE Dale Sievert. 40 HOMEGROWN HARVEST Love those leeks! page 400 42 GARDEN SOLUTIONS Understanding mycorrhizal fungi. BOOK REVIEWS page 18 44 The Seed Garden and Rescuing Eden. Special focus: Wild 12 NEW PLANTS FOR 2016 BY CHARLOTTE GERMANE gardening. From annuals and perennials to shrubs, vines, and vegetables, see which of this year’s introductions are worth trying in your garden. 46 GARDENER’S NOTEBOOK Link discovered between soil fungi and monarch 18 THE DWARF TOMATO PROJECT BY CRAIG LEHOULLIER butterfl y health, stinky A worldwide collaborative breeds diminutive plants that produce seeds trick dung beetles into dispersal role, regular-size, fl avorful tomatoes. Mt. Cuba tickseed trial results, researchers unravel how plants can survive extreme drought, grant for nascent public garden in 24 BEST SMALL BROADLEAVED EVERGREENS Delaware, Lady Bird Johnson Wildfl ower BY ANDREW BUNTING Center selects new president and CEO. These small to mid-size selections make a big impact in modest landscapes. 50 GREEN GARAGE Seed-starting products. 30 WEESIE SMITH BY ALLEN BUSH 52 TRAVELER’S GUIDE TO GARDENS Alabama gardener Weesie Smith championed pagepage 3030 Quarryhill Botanical Garden, California. -

Alternative Hosts of Crapemyrtle Bark Scale Mengmeng Gu Associate Professor and Extension Ornamental Horticulturist the Texas A&M University System

EHT-103 5/18 Alternative Hosts of Crapemyrtle Bark Scale Mengmeng Gu Associate Professor and Extension Ornamental Horticulturist The Texas A&M University System Crapemyrtle bark scale (Acanthococcus lager- stroemiae) has been confirmed in all the South- eastern U.S. except for Florida. In its native range in East Asia, CMBS is a serious threat to crapemyrtles, persimmons, and pomegranate plants. In the U.S., it is an emerging pest that threatens crapemyrtle production and land- scape use. This is a matter of concern because Fig. 1. A crapemyrtle plant infested crapemyrtle is the highest selling flowering with crapemyrtle bark scale. tree—5 million plants with a combined value of $67M were sold in 2014. Currently, CMBS in the U.S. is only reported Among the documented plants infested by on crapemyrtles, but the spread of CMBS (con- CMBS, other economically important crops firmed by molecular identification) to native include boxwood, soybean, fig, myrtle, cleyera, American beautyberry plants in Texarkana, TX apple, and brambles, such as blackberry, rasp- and Shreveport, LA is alarming. This finding berry, dewberry, juneberry etc. Since Chinese brings to 14 the number of economically and hackberry is identified as a host plant, this raises ecologically important plant families reported concern that the native hackberry—widely as host plants in the CMBS regions of origin established in common crapemyrtle growing (Table 1). regions—may be a possible target species. Table 1. 1. Buxaceae: Buxus 8. Moraceae: Ficus carica 2. Cannabaceae: Celtis sinensis 9. Myrtaceae: Myrtus 3. Combretaceae: Anogeissus, Anogeissus latifolia 10. Oleaceae: Ligustrum obtusifolium 4. Ebenaceae: Diospyros kaki 11.