AA Bronson Radical Asshole '…The Use of Irony Was Itself Serious

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Constellation & Correspondences

LIBRARY CONSTELLATION & CORRESPONDENCES AND NETWORKING BETWEEN ARTISTS ARCHIVES 1970 –1980 KATHY ACKER (RIPOFF RED & THE BLACK TARANTULA) MAC ADAMS ART & LANGUAGE DANA ATCHLEY (THE EXHIBITION COLORADO SPACEMAN) ANNA BANANA ROBERT BARRY JOHN JACK BAYLIN ALLAN BEALY PETER BENCHLEY KATHRYN BIGELOW BILL BISSETT MEL BOCHNER PAUL-ÉMILE BORDUAS GEORGE BOWERING AA BRONSON STU BROOMER DAVID BUCHAN HANK BULL IAN BURN WILLIAM BURROUGHS JAMES LEE BYARS SARAH CHARLESWORTH VICTOR COLEMAN (VIC D'OR) MARGARET COLEMAN MICHAEL CORRIS BRUNO CORMIER JUDITH COPITHORNE COUM KATE CRAIG (LADY BRUTE) MICHAEL CRANE ROBERT CUMMING GREG CURNOE LOWELL DARLING SHARON DAVIS GRAHAM DUBÉ JEAN-MARIE DELAVALLE JAN DIBBETS IRENE DOGMATIC JOHN DOWD LORIS ESSARY ANDRÉ FARKAS GERALD FERGUSON ROBERT FILLIOU HERVÉ FISCHER MAXINE GADD WILLIAM (BILL) GAGLIONE PEGGY GALE CLAUDE GAUVREAU GENERAL IDEA DAN GRAHAM PRESTON HELLER DOUGLAS HUEBLER JOHN HEWARD DICK NO. HIGGINS MILJENKO HORVAT IMAGE BANK CAROLE ITTER RICHARDS JARDEN RAY JOHNSON MARCEL JUST PATRICK KELLY GARRY NEILL KENNEDY ROY KIYOOKA RICHARD KOSTELANETZ JOSEPH KOSUTH GARY LEE-NOVA (ART RAT) NIGEL LENDON LES LEVINE GLENN LEWIS (FLAKEY ROSE HIPS) SOL LEWITT LUCY LIPPARD STEVE 36 LOCKARD CHIP LORD MARSHALORE TIM MANCUSI DAVID MCFADDEN MARSHALL MCLUHAN ALBERT MCNAMARA A.C. MCWHORTLES ANDREW MENARD ERIC METCALFE (DR. BRUTE) MICHAEL MORRIS (MARCEL DOT & MARCEL IDEA) NANCY MOSON SCARLET MUDWYLER IAN MURRAY STUART MURRAY MAURIZIO NANNUCCI OPAL L. NATIONS ROSS NEHER AL NEIL N.E. THING CO. ALEX NEUMANN NEW YORK CORRES SPONGE DANCE SCHOOL OF VANCOUVER HONEY NOVICK (MISS HONEY) FOOTSY NUTZLE (FUTZIE) ROBIN PAGE MIMI PAIGE POEM COMPANY MEL RAMSDEN MARCIA RESNICK RESIDENTS JEAN-PAUL RIOPELLE EDWARD ROBBINS CLIVE ROBERTSON ELLISON ROBERTSON MARTHA ROSLER EVELYN ROTH DAVID RUSHTON JIMMY DE SANA WILLOUGHBY SHARP TOM SHERMAN ROBERT 460 SAINTE-CATHERINE WEST, ROOM 508, SMITHSON ROBERT STEFANOTTY FRANÇOISE SULLIVAN MAYO THOMSON FERN TIGER TESS TINKLE JASNA MONTREAL, QUEBEC H3B 1A7 TIJARDOVIC SERGE TOUSIGNANT VINCENT TRASOV (VINCENT TARASOFF & MR. -

The Estate of General Idea: Ziggurat, 2017, Courtesy of Mitchell-Innes and Nash

Installation view of The Estate of General Idea: Ziggurat, 2017, Courtesy of Mitchell-Innes and Nash. © General Idea. The Estate of General Idea (1969-1994) had their first exhibition with the Mitchell-Innes & Nash Gallery on view in Chelsea through January 13, featuring several “ziggurat” paintings from the late 1960s, alongside works on paper, photographs and ephemera that highlight the central importance of the ziggurat form in the rich practice of General Idea. It got me thinking about the unique Canadian trio’s sumptuous praxis and how it evolved from humble roots in the underground of the early 1970s to its sophisticated position atop the contemporary art world of today. One could say that the ziggurat form is a perfect metaphor for a staircase of their own making that they ascended with grace and elegance, which is true. But they also had to aggressively lacerate and burn their way to the top, armed with real fire, an acerbic wit and a penchant for knowing where to apply pressure. Even the tragic loss of two thirds of their members along the way did not deter their rise, making the unlikely climb all the more heroic. General Idea, VB Gown from the 1984 Miss General Idea Pageant, Urban Armour for the Future, 1975, Gelatin Silver Print, 10 by 8 in. 25.4 by 20.3 cm, Courtesy Mitchell-Innes and Nash. © General Idea. The ancient architectural structure of steps leading up to a temple symbolizes a link between humans and the gods and can be found in cultures ranging from Mesopotamia to the Aztecs to the Navajos. -

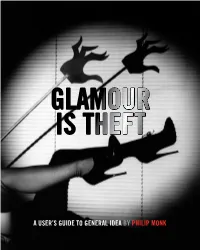

A USER's GUIDE to GENERAL IDEA by PHILIP Monk

GLAMOUR IS THEFT A USER’S GUIDE TO GENERAL IDEA BY PHILIP MONk Portrait of Granada Gazelle, Miss General Idea 1969, from The 1971 Miss General Idea Pageant documentation, 1971 1 Granada Gazelle, Miss General Idea 1969, displays The 1971 Miss General Idea Pageant Entry Kit The 1971 Miss General Idea Pageant poster, 1971 4 The 1971 Miss General Idea Pageant (Artscanada), 1971 5 6 7 Artist’s Conception: Miss General Idea 1971, 1971 8 GLAMOUR IS THEFT A USER’S GUIDE TO GENERAL IDEA: 1969-1978 PHILIP MONk The Art Gallery of York University “Top Ten,” FILE 1:2&3 (May/June 1972), 21 10 TABLE OF CONTENTS 15 PreFace PART I. DESCRIPTIVE PART II. ANALYTIC PART III. SYNTHETIC 21 threshold 121 reWrIte 157 soMethInG By Mouth 25 announceMent 131 Ideolect 29 Myth 135 enuncIatIon 37 edItorIal 141 systeM 41 story 147 vIce versa 45 PaGeant 49 sIMulatIon 53 vIrus 57 Future 61 PavIllIon 67 nostalGIa 75 BorderlIne 81 PuBlIcIty 87 GlaMour 93 PlaGIarIsM 103 role 111 crIsIs APPENDICES 209 Marshall Mcluhan, General Idea, and Me! 221 PerIodIzInG General Idea EXHIBITIONS 233 GoInG thru the notIons (1975) 241 reconstructInG Futures (1977) 245 the 1984 MIss General Idea PavIllIon (2009) 254 lIst oF WorKs 255 acKnoWledGeMents 11 Portrait of General Idea, 1974 (photograph by Rodney Werden) The study of myths raises a methodological problem, in that it cannot be carried out according to the Cartesian principle of breaking down the difficulty into as many parts as may be necessary for finding the solution. There is no real end to mythological analysis, no hidden unity to be grasped once the breaking-down process has been completed. -

This World & Nearer Ones Nyc's First

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE MEDIA CONTACT Nicholas Weist, Creative Time [email protected] 212.206.6674 x 205 CREATIVE TIME PRESENTS PLOT09: THIS WORLD & NEARER ONES NYC’S FIRST PUBLIC ART QUADRENNIAL, ON GOVERNORS ISLAND, NYC 19 public art commissions by major international artists Free, Opening June 27 Work by Mark Wallinger, Lawrence Weiner, Anthony McCall, Krzysztof Wodiczko, Patti Smith, AA Bronson, and more PLOT09: This World & Nearer Ones Opening June 27 Free and open to the public Fridays 11-4 and Saturdays and Sundays, 12-6 Digital press center: http://creativetime.org/programs/archive/2009/GI/ (May 29, 2009 New York, NY) Creative Time is pleased to announce its new public art quadrennial: PLOT, taking place on historic Governors Island and featuring international artists responding to the island with new, site-responsive artworks. The first edition of PLOT, This World & Nearer Ones, is curated by Mark Beasley. The project is produced in association with Governors Island Preservation and Education Corporation, the National Park Service, NYC & Company, and the Office of the Mayor. PLOT09 will draw thousands to Governors Island to explore the artwork and numerous other public programs. PLOT09 is free and open to the public, and will open on June 27. This World & Nearer Ones will intervene in the architectural and natural fabric of the island, transforming its historic buildings and vast lawns—from the iconic Fort Jay to St. Cornelius Chapel—through installation, performance, video, and auditory works, inviting audiences to reconsider the island’s past and future. PLOT09 will feature artists from 9 different countries, including Edgar Arceneaux, AA Bronson and Peter Hobbs, The Bruce High Quality Foundation, Adam Chodzko, Tue Greenfort, Jill Magid, Teresa Margolles, Anthony McCall, Nils Norman, Susan Philipsz, Patti Smith and Jesse Smith, Tercerunquinto, Tris Vonna-Michell, Mark Wallinger, Klaus Weber, Lawrence Weiner, Judi Werthein, Guido van der Werve, and Krzysztof Wodiczko, realizing temporary projects in various sites throughout Governors Island. -

MAUREEN PALEY. Press Release AA BRONSON + GENERAL IDEA 30 September

MAUREEN PALEY. press release AA BRONSON + GENERAL IDEA 30 September – 11 November 2018 private view: Sunday 30 September 5:30 – 7:30 pm The exhibition marks fifty years since AA Bronson, Felix Partz and Jorge Zontal first met in 1968, initiating their collaboration as the Canadian collective General Idea the following year. Over the course of twenty five years (1969-1994), they lived and worked together to produce the living artwork of their being together, undertaking over 100 solo exhibitions, countless group shows and temporary public art projects. They were known for their magazine FILE (1972-1989), their unrelenting production of numerous multiples, and their early involvement in punk, queer theory and AIDS activism. The celebrated publication FILE appropriated the design of LIFE magazine; some of the most radical artists and collectives of the period contributed to FILE, among them Art & Language, writer William Burroughs, and bands such as Talking Heads and The Residents. The adoption of the existing mass-market format of LIFE magazine set up a sustained interest in the possibility of using ‘found formats’ as ‘hosts’ for their ideas. From 1987 through 1994, working primarily in New York City, General Idea’s work addressed the AIDS crisis and produced their best known work to date - Imagevirus. Reappropriating Robert Indiana’s work LOVE - substituting, in the same visual arrangement and colour composition, the letters L-O-V-E with A-I-D-S – they used the mechanism of viral transmission to investigate the term as both word and image. The series took the form of paintings, sculptures, postage stamps, posters and magazine covers. -

Paul O'neill and Aa Bronson

PAU L O ’ N E I L L A N D AA B R on S on New York, 2004–2006 PAUL: Maybe we could start by tracing the beginning of the history of General Idea? AA: General Idea happened by accident. It was the late ‘60s in Toronto and our friend Mimi (who was Felix Partz’s girlfriend) found this old house, 78 Gerrard Street West, and convinced us to move in together to save rent. There were about eight of us and we were all more or less straight out of school. We moved in to the house, which at one point had been turned into a shop. It was the late ‘60s, the pop era, there were flowers painted on the street, and now the street had more or less died down and the action had moved to some other part of town. We moved into this rather forlorn house, which had a store window punched into the living room; we were all unemployed, mostly artists, and we were a little bored. We began rummaging through the garbage of the various neighboring businesses, and we began to AA Bronson (right) and Mark Krayenhoff (left) assemble fake stores in our store window. We did window Printed Matter, 10th Avenue, New York, NY, 2005 displays essentially. We didn’t think of it as art at the Photo: Paul O’Neill. time, we were just entertaining ourselves. Sometimes the displays got out of hand. We would have to give up are sort of illuminated today in particular ways, but I our living room to them; we did immense displays that won’t get into too many of them. -

The Artist As a Work-In-Progress: General Idea and the Construction of Collective Identity

Forum for Modern Language Studies Vol. 48,No.4, doi: 10.1093/fmls/cqs022 THE ARTIST AS A WORK-IN-PROGRESS: GENERAL IDEA AND THE CONSTRUCTION OF COLLECTIVE IDENTITY DEBORAH BARKUN ABSTRACT Downloaded from In its twenty-five years of activity (1969–1994), the art collective General Idea developed a complex artistic mythology and identity that permitted it to produce a substantial corpus of work while confronting challenges provoked by evolving social relationships and, eventually, HIV/AIDS. The group main- tained a cohesive partnership, a ‘collaborative body’ that subsumed individual members’ identities within a collective whole. This paper analyses the concep- http://fmls.oxfordjournals.org/ tual projects and artists’ statements of the group’s first decade, many of which belong to the domain of Correspondence and Mail Art. It argues that these textual and performative artworks strategically constructed an elaborate collect- ive identity. They equally functioned as a vehicle through which to develop methods and strategies of collaborative practice, reflecting debates about authorship such as those theorized contemporaneously by Roland Barthes and Michel Foucault. Keywords: General Idea; collaboration; authorship; collectivity; Correspondence Art; Conceptual Art; Mail Art; manifesto; performance; gender; sexuality by guest on October 16, 2012 IN 1969,CANADIAN ARTISTS AA Bronson (b. Michael Tims), Jorge Zontal (b. Slobodan Saia-Levi) and Felix Partz (b. Ron Gabe) formed a multimedia art collective named General Idea (Figure 1).1 General Idea’s formation was less deliberate than organic, a process evoked by the biological metaphors the group later used to characterize its collaboration, and the concepts and dissemination of its work. -

On Kawara 29,771 Days

This document was updated February 26, 2021. For reference only and not for purposes of publication. For more information, please contact the gallery. On Kawara 29,771 days SOLO EXHIBITIONS 2020 On Kawara and the Grande Complication, Mathematisch-Physikalischer Salon, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden 2019 On Kawara, David Lamelas, Jan Mot Gallery, Brussels [two-person exhibition] 2018 On Kawara, Krakow Witkin Gallery, Boston On Kawara: One Million Years (Reading), Museum MACAN, Jakarta, Indonesia 2017 On Kawara: One Million Years, Oratorio di San Ludovico Dorsoduro, Venice [organized by Ikon Gallery, Birmingham, England as part of 57th Venice Biennale] 2015 On Kawara: 1966, Museum Dhondt-Dhaenens, Deurle, Belgium [catalogue] On Kawara: One Million Years, Asia House, London On Kawara—Silence, Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York [catalogue] 2013 On Kawara: One Million Years, BOZAR - Centre for Fine Arts, Brussels 2012 On Kawara: Date Painting(s) in New York and 136 Other Cities, David Zwirner, New York [catalogue] On Kawara - Lived Time, Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen, Rotterdam On Kawara: One Million Years, BALTIC Centre for Contemporary Art, Gateshead, England On Kawara: One Million Years, Jardin des Plantes, Paris 2010 On Kawara: Pure Consciousness at 19 Kindergartens, Walter and McBean Galleries, San Francisco Art Institute 2009 On Kawara: One Million Years, David Zwirner, New York 2008 On Kawara: 10 Tableaux and 16,952 Pages, Dallas Museum of Art [catalogue] 2007 On Kawara, Michèle Didier at Christophe Daviet-Théry, Paris 2006 Eternal -

Jean-Noel Archive.Qxp.Qxp

THE JEAN-NOËL HERLIN ARCHIVE PROJECT Jean-Noël Herlin New York City 2005 Table of Contents Introduction i Individual artists and performers, collaborators, and groups 1 Individual artists and performers, collaborators, and groups. Selections A-D 77 Group events and clippings by title 109 Group events without title / Organizations 129 Periodicals 149 Introduction In the context of my activity as an antiquarian bookseller I began in 1973 to acquire exhibition invitations/announcements and poster/mailers on painting, sculpture, drawing and prints, performance, and video. I was motivated by the quasi-neglect in which these ephemeral primary sources in art history were held by American commercial channels, and the project to create a database towards the bibliographic recording of largely ignored material. Documentary value and thinness were my only criteria of inclusion. Sources of material were random. Material was acquired as funds could be diverted from my bookshop. With the rapid increase in number and diversity of sources, my initial concept evolved from a documentary to a study archive project on international visual and performing arts, reflecting the appearance of new media and art making/producing practices, globalization, the blurring of lines between high and low, and the challenges to originality and quality as authoritative criteria of classification and appreciation. In addition to painting, sculpture, drawing and prints, performance and video, the Jean-Noël Herlin Archive Project includes material on architecture, design, caricature, comics, animation, mail art, music, dance, theater, photography, film, textiles and the arts of fire. It also contains material on galleries, collectors, museums, foundations, alternative spaces, and clubs. -

Clive Robertson, Associate Professor (Tenured)

Curriculum Vitae Name: Clive Robertson, Associate Professor (tenured) Degrees: Ph.D Concordia, Communication Studies, 2004 MFA University of Reading, England, Fine Art, 1971 Diploma in Art and Design (1st Class Hon) Fine Art, Cardiff College of Art, 1969 Employment History: 2010-11 Acting Head, Department of Art: Fine Art, Art Conservation and Art History, Queen’s University 2009 Associate Faculty, Graduate Program in Cultural Studies, Queen’s University Undergrad Chair, Art History, Queen’s University 2005 - Associate Professor, Art Department, Queen’s University 1999-2005 Assist. Professor, Contemporary Art History, Policy and Performance Studies, Department of Art, Queen’s University, Kingston 1998 Adjunct Lecturer, Contemporary Canadian Art History, Queen’s University 1996 Adjunct Lecturer, Contemporary Canadian Art History, Art Dept, Queen’s University, Kingston 1996 Part-time Lecturer, Audio Production, Diploma Program, Communication Studies, Concordia University 1991-6 (Freelance) Independent media arts curator, Ottawa 1989-91 National Spokesperson, ANNPAC/RACA, Toronto and Ottawa. 1990 Co-National Director, ANNPAC/RACA (Association of National Non- Profit Artist-run Centres), Ottawa. 1987-89 Artistic Director, Galerie SAW Video, Ottawa. 1985-6 Video Production Co-ordinator, Trinity Square Video, Toronto. 1983-5 Publisher and Executive Producer, Voicespondence Artists Records and Tapes, Toronto 1981 Sessional Instructor, Intermedia, Ottawa School of Art. 1980 Adjunct Lecturer, Media Arts, Simon Fraser University, Vancouver. 1973 -

![GENERAL IDEA COLLECTIVE MEMBERS AA Bronson [B. 1946, Vancouver; Lives and Works in Toronto and Berlin] Felix Partz [B. 1945](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8440/general-idea-collective-members-aa-bronson-b-1946-vancouver-lives-and-works-in-toronto-and-berlin-felix-partz-b-1945-6008440.webp)

GENERAL IDEA COLLECTIVE MEMBERS AA Bronson [B. 1946, Vancouver; Lives and Works in Toronto and Berlin] Felix Partz [B. 1945

GENERAL IDEA COLLECTIVE MEMBERS AA Bronson [b. 1946, Vancouver; lives and works in Toronto and Berlin] Felix Partz [b. 1945, Winnipeg, Canada, d. 1994, Toronto] Jorge Zontal [b. 1944, Parma, Italy, d. 1994, Toronto] SELECTED SOLO EXHIBITIONS 2019 General Idea, Mai 36 Galerie, Zurich, Switzerland 2018 AA Bronson + General Idea, Maureen Paley, London, England 2017 Ziggurat, Mitchell-Innes & Nash, New York, NY Broken Time/Tiempo Partido, Museo de Arte Latinoamericano de Buenos Aires Malba, Buenos Aires, Argentina Photographs (1969-1982), Musée d’art Moderne et Contemporain, Geneva, Switzerland 2016 Broken Time/Tiempo Partido, Fondation Jumex, Mexico City, Mexico 2013 P is for Poodle, Mai 36 Galerie, Zurich, Switzerland P is for Poodle, Esther Schipper, Berlin, Germany General Idea, Taro Nasu Gallery, Tokyo, Japan 2011 Haute Culture: General Idea. Une retrospective, 1969-1994, Musée d’art moderne de la ville de Paris, Paris; Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto, Canada FILE Magazine/General Idea Editions, Torpedo Kunstbokhandelen, Oslo, Norway 2010 Editionen und Multiples, Helga Maria Klosterfelde Edition, Berlin, Germany 2009 Works 1987 – 1994, Mai 36 Galerie, Zurich, Switzerland Works 1968 – 1975, Esther Schipper, Berlin, Germany The 1984 Miss General Idea Pavillion, The Art Gallery of York University, Toronto, Canada 2008 Works 1968-1995, Stampa Gallery, Basel, Switzerland 2007 Sex + Death, Galerie Fréderic Giroux, Paris, France General Ideal Editions: 1967-1995, Henry Art Gallery, Seattle, WA; Centro Andaluz de Arte Contemporáneo, Seville, -

Communities Between Culture-By-Mouth and Culture-By-Media

Communities Between Culture-by-Mouth and Culture-by-Media Luis ]acob THE 1971 MISS GENERAL IDEA PAGEANT Dowrllt'l<farior/ 0/1 rl~/d,;}~ 'it.'1 Spdrc, ~5 Si. Sit/wit,s SfH'L'I, SCPU!III!Jcr l4-],J. The Gr<1lu! A.lllilrd.~ Ct'{('III:'IJY Il'iil be held III tht' :4rt Caller)' ~r OH/d';t', Fri&I),. OUtlba.!irSf IIf S:O<J jl-1iI. General Idea, poster for the 1971 Miss General Idea Pageant Luis Jacob 87 Historical continuity is the Achilles heel ofToronto artmaking. More precisely, the absence in this city of a sense of historical continuity renders the act of making art into a poignant but self-defeating gesture. When was the last time you found a piece of writing dealing with the relationship between a current production in this city and what has gone on before it? When was the last time you were able to attend a retrospective exhibition on the work of a Toronto artist? If we agree that artistic production is a communicative practice-an exercise in which the meaning of community becomes an issue-then a lack of historical context amounts to something like a lack of language, which is to say that artistic production would somehow have to exist without publicness. Exhibition would follow exhibition, artist would follow artist, decade would follow decade-and quickly each of these would sink into our collective amnesia, into the black hole of cultural disregard. One must ask what this situation would mean for artists. How would a person-especially a young one-envision being an artist in the face of this radical atomization without a public, without a language, and without a future? Making art is defeated in advance if artists are unable to create, or even to imagine, their own ideal audience and the world for which their work is created.