The King of Zines: AA Bronson's Reflections on Artists' Books And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Constellation & Correspondences

LIBRARY CONSTELLATION & CORRESPONDENCES AND NETWORKING BETWEEN ARTISTS ARCHIVES 1970 –1980 KATHY ACKER (RIPOFF RED & THE BLACK TARANTULA) MAC ADAMS ART & LANGUAGE DANA ATCHLEY (THE EXHIBITION COLORADO SPACEMAN) ANNA BANANA ROBERT BARRY JOHN JACK BAYLIN ALLAN BEALY PETER BENCHLEY KATHRYN BIGELOW BILL BISSETT MEL BOCHNER PAUL-ÉMILE BORDUAS GEORGE BOWERING AA BRONSON STU BROOMER DAVID BUCHAN HANK BULL IAN BURN WILLIAM BURROUGHS JAMES LEE BYARS SARAH CHARLESWORTH VICTOR COLEMAN (VIC D'OR) MARGARET COLEMAN MICHAEL CORRIS BRUNO CORMIER JUDITH COPITHORNE COUM KATE CRAIG (LADY BRUTE) MICHAEL CRANE ROBERT CUMMING GREG CURNOE LOWELL DARLING SHARON DAVIS GRAHAM DUBÉ JEAN-MARIE DELAVALLE JAN DIBBETS IRENE DOGMATIC JOHN DOWD LORIS ESSARY ANDRÉ FARKAS GERALD FERGUSON ROBERT FILLIOU HERVÉ FISCHER MAXINE GADD WILLIAM (BILL) GAGLIONE PEGGY GALE CLAUDE GAUVREAU GENERAL IDEA DAN GRAHAM PRESTON HELLER DOUGLAS HUEBLER JOHN HEWARD DICK NO. HIGGINS MILJENKO HORVAT IMAGE BANK CAROLE ITTER RICHARDS JARDEN RAY JOHNSON MARCEL JUST PATRICK KELLY GARRY NEILL KENNEDY ROY KIYOOKA RICHARD KOSTELANETZ JOSEPH KOSUTH GARY LEE-NOVA (ART RAT) NIGEL LENDON LES LEVINE GLENN LEWIS (FLAKEY ROSE HIPS) SOL LEWITT LUCY LIPPARD STEVE 36 LOCKARD CHIP LORD MARSHALORE TIM MANCUSI DAVID MCFADDEN MARSHALL MCLUHAN ALBERT MCNAMARA A.C. MCWHORTLES ANDREW MENARD ERIC METCALFE (DR. BRUTE) MICHAEL MORRIS (MARCEL DOT & MARCEL IDEA) NANCY MOSON SCARLET MUDWYLER IAN MURRAY STUART MURRAY MAURIZIO NANNUCCI OPAL L. NATIONS ROSS NEHER AL NEIL N.E. THING CO. ALEX NEUMANN NEW YORK CORRES SPONGE DANCE SCHOOL OF VANCOUVER HONEY NOVICK (MISS HONEY) FOOTSY NUTZLE (FUTZIE) ROBIN PAGE MIMI PAIGE POEM COMPANY MEL RAMSDEN MARCIA RESNICK RESIDENTS JEAN-PAUL RIOPELLE EDWARD ROBBINS CLIVE ROBERTSON ELLISON ROBERTSON MARTHA ROSLER EVELYN ROTH DAVID RUSHTON JIMMY DE SANA WILLOUGHBY SHARP TOM SHERMAN ROBERT 460 SAINTE-CATHERINE WEST, ROOM 508, SMITHSON ROBERT STEFANOTTY FRANÇOISE SULLIVAN MAYO THOMSON FERN TIGER TESS TINKLE JASNA MONTREAL, QUEBEC H3B 1A7 TIJARDOVIC SERGE TOUSIGNANT VINCENT TRASOV (VINCENT TARASOFF & MR. -

The Estate of General Idea: Ziggurat, 2017, Courtesy of Mitchell-Innes and Nash

Installation view of The Estate of General Idea: Ziggurat, 2017, Courtesy of Mitchell-Innes and Nash. © General Idea. The Estate of General Idea (1969-1994) had their first exhibition with the Mitchell-Innes & Nash Gallery on view in Chelsea through January 13, featuring several “ziggurat” paintings from the late 1960s, alongside works on paper, photographs and ephemera that highlight the central importance of the ziggurat form in the rich practice of General Idea. It got me thinking about the unique Canadian trio’s sumptuous praxis and how it evolved from humble roots in the underground of the early 1970s to its sophisticated position atop the contemporary art world of today. One could say that the ziggurat form is a perfect metaphor for a staircase of their own making that they ascended with grace and elegance, which is true. But they also had to aggressively lacerate and burn their way to the top, armed with real fire, an acerbic wit and a penchant for knowing where to apply pressure. Even the tragic loss of two thirds of their members along the way did not deter their rise, making the unlikely climb all the more heroic. General Idea, VB Gown from the 1984 Miss General Idea Pageant, Urban Armour for the Future, 1975, Gelatin Silver Print, 10 by 8 in. 25.4 by 20.3 cm, Courtesy Mitchell-Innes and Nash. © General Idea. The ancient architectural structure of steps leading up to a temple symbolizes a link between humans and the gods and can be found in cultures ranging from Mesopotamia to the Aztecs to the Navajos. -

AA Bronson Radical Asshole '…The Use of Irony Was Itself Serious

AA Bronson Radical Asshole ‘…the use of irony was itself serious…’ – AA Bronson on General Idea, in The Confession of AA Bronson (2011) AA Bronson thinks his butt is revolutionary. That may be the case – I haven’t tried it – but I’m not quoting him fairly. He thinks all assholes are revolutionary. In this he joins proto-queer thinker Guy Hocquenghem, who argued that the liberation of anal pleasure from shame was one way to remake society as a whole. Homosexuality is dangerous, he claimed in Homosexual Desire (1972), because it shows that eroticism is not tied to reproduction. Male receptivity further disturbs the masculine/feminine, active/passive oppositions which uphold patriarchal authority and by extension marriage or other systems of ownership. This undoing of gendered mastery finds echoes in Bronson’s earlier work as a member of General Idea. From their mock beauty pageants in which the artist becomes feminised commodity, to their pose as pampered poodles, they mercilessly satirised the singular (straight male) artistic genius as a myth of the media and marketplace. But the deaths of his partners and collaborators Jorge Zontal and Felix Partz from AIDS in 1994, and his reversion to working alone, caused not only a personal but an artistic crisis for Bronson. How could he represent himself without betraying the group’s critique of the artist as gifted individual? While his most recent work has sought to memorialise those lost to the pandemic and histories of homophobic persecution, his decision to summon the queerly departed by posing, like Joseph Beuys, as a shaman, appears to abandon the principles of GI. -

Manifestopdf Cover2

A Manifesto for the Book Sarah Bodman and Tom Sowden A Manifesto for the Book Sarah Bodman and Tom Sowden with an edited selection of interviews, essays and case studies from the project What will be the canon for the artist’s book in the 21st Century? 1 A Manifesto for the Book Published by Impact Press at The Centre for Fine Print Research University of the West of England, Bristol February 2010 Free download from: http://www.bookarts.uwe.ac.uk/canon.htm This publication is a result of a project funded by the Arts and Humanities Research Council from March 2008 - February 2010: What will be the canon for the artist’s book in the 21st Century? The AHRC funds postgraduate training and research in the arts and humanities, from archaeology and English literature to design and dance. The quality and range of research supported not only provides social and cultural benefits but also contributes to the economic success of the UK. For further information on the AHRC, please see the website www.ahrc.ac.uk ISBN 978-1-906501-04-4 © 2010 Publication, Impact Press © 2010 Images, individual artists © 2010 Texts, individual authors Editors Sarah Bodman and Tom Sowden The views expressed within A Manifesto for the Book are not necessarily those of the editors or publisher. Impact Press, Centre for Fine Print Research UWE, Bristol School of Creative Arts Kennel Lodge Road, Bristol BS3 2JT United Kingdom Tel: +44 (0) 117 32 84915 Fax: +44 (0) 117 32 85865 www.bookarts.uwe.ac.uk [email protected] [email protected] 2 Contents Interview with Eriko Hirashima founder of LA LIBRERIA artists’ bookshop in Singapore 109 A Manifesto for the Book Sarah Bodman and Tom Sowden 5 Interview with John Risseeuw, proprietor of his own Cabbagehead Press and Director of ASU’s Pyracantha Interview with Radoslaw Nowakowski on publishing his own Press, Arizona State University, USA 113 books and artists’ books “non-describing the world” since the 70s in Dabrowa Dolna, Poland. -

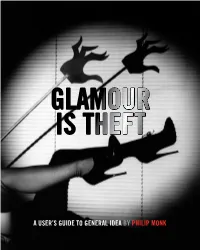

A USER's GUIDE to GENERAL IDEA by PHILIP Monk

GLAMOUR IS THEFT A USER’S GUIDE TO GENERAL IDEA BY PHILIP MONk Portrait of Granada Gazelle, Miss General Idea 1969, from The 1971 Miss General Idea Pageant documentation, 1971 1 Granada Gazelle, Miss General Idea 1969, displays The 1971 Miss General Idea Pageant Entry Kit The 1971 Miss General Idea Pageant poster, 1971 4 The 1971 Miss General Idea Pageant (Artscanada), 1971 5 6 7 Artist’s Conception: Miss General Idea 1971, 1971 8 GLAMOUR IS THEFT A USER’S GUIDE TO GENERAL IDEA: 1969-1978 PHILIP MONk The Art Gallery of York University “Top Ten,” FILE 1:2&3 (May/June 1972), 21 10 TABLE OF CONTENTS 15 PreFace PART I. DESCRIPTIVE PART II. ANALYTIC PART III. SYNTHETIC 21 threshold 121 reWrIte 157 soMethInG By Mouth 25 announceMent 131 Ideolect 29 Myth 135 enuncIatIon 37 edItorIal 141 systeM 41 story 147 vIce versa 45 PaGeant 49 sIMulatIon 53 vIrus 57 Future 61 PavIllIon 67 nostalGIa 75 BorderlIne 81 PuBlIcIty 87 GlaMour 93 PlaGIarIsM 103 role 111 crIsIs APPENDICES 209 Marshall Mcluhan, General Idea, and Me! 221 PerIodIzInG General Idea EXHIBITIONS 233 GoInG thru the notIons (1975) 241 reconstructInG Futures (1977) 245 the 1984 MIss General Idea PavIllIon (2009) 254 lIst oF WorKs 255 acKnoWledGeMents 11 Portrait of General Idea, 1974 (photograph by Rodney Werden) The study of myths raises a methodological problem, in that it cannot be carried out according to the Cartesian principle of breaking down the difficulty into as many parts as may be necessary for finding the solution. There is no real end to mythological analysis, no hidden unity to be grasped once the breaking-down process has been completed. -

A Case Study of Project Space by Tracy Ann Stefanucci Bachelor Of

Making Space for Publication: A Case Study of Project Space by Tracy Ann Stefanucci Bachelor of Education, University of British Columbia, 2009 Bachelor of Fine Arts, University of British Columbia, 2008 PROJECT SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF PUBLISHING in the Publishing Program Faculty of Communication Art and Technology © Tracy Ann Stefanucci 2016 SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY Summer 2016 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-4.0 International License. You are free to share—copy and redistribute the material in any medium or format—and adapt— remix, transform, and build upon the material. Approval Name: Tracy Ann Stefanucci Degree: Master of Publishing Title of Project: Making Space for Publication: A Case Study of Project Space Dr John W Maxwell Associate Professor, Publishing Program, Senior Supervisor Mauve Page Lecturer, Publishing Program, Supervisor Leanne Johnson Gave and Took Publishing, Vancouver BC Industry Supervisor Brian McBay Director, 221A, Vancouver, BC Industry Supervisor Date Approved: May 18, 2016 ii Abstract The proliferation of digital technologies has initiated a need for radical changes to publishing business models, while simultaneously laying the foundation for a renaissance of the print book akin to that which occurred in the 1960s and 70s. This “second wave of self-publishing” has come about as a widespread surge, particularly in the realm of contemporary art and graphic design, but also in literary and DIY circles. As was the case in the “first wave,” this expansion has resulted in the development of brick-and-mortar spaces that house and nurture the activities of this niche, particularly the production of publications, exhibitions and additional programming (such as lectures and workshops). -

BOOK ARTS NEWSLETTER ISSN 1754-9086 No

BOOK ARTS NEWSLETTER ISSN 1754-9086 No. 76 September - October 2012 Published by Impact Press at the Centre for Fine Print Research, UWE Bristol, UK ARTIST’S COVER PAGE: LONDON CENTRE FOR BOOK ARTS (SEE PAGE 19!) IN THIS ISSUE: NATIONAL AND INTERNATIONAL ARTISTS’ BOOKS EXHIBITIONS PAGES 1 - 19 ANNOUNCEMENTS PAGES 19 - 20 COURSES, LECTURES & WORKSHOPS PAGES 20 - 26 OPPORTUNITIES PAGES 26 - 28 ARTIST’S BOOK FAIRS PAGES 28 - 30 INTERNET NEWS PAGES 30 - 32 NEW ARTISTS’ PUBLICATIONS PAGES 32 - 45 REPORTS & REVIEWS PAGES 45 - 49 STOP PRESS! PAGES 49 - 51 Artists’ Books Exhibition, UWE, Bristol, UK technology and science. The advantage of image over text Tom Trusky Exhibition Cases, Bower Ashton Library is that all layers of meaning can be seen simultaneously, and don’t have to be read one after the other in a linear Otto fashion. Furthermore, different ways of constructing the 3rd September - 30th October 2012 book as an object can encourage and offer different ways of Otto is a graphic artist who practices as an illustrator, reading. Alternative folding techniques allow for non-linear screenprinter and book artist. narratives that develop laterally. Since graduating in 1991 from Bristol Polytechnic with a BA Hons in Graphic Design he has been working as freelance illustrator and has been illustrating political, social and economic subjects for international newspapers and magazines. Otto’s image-making is influenced by Russian Constructivist designs, Polish poster art and Renaissance painting. Alien invasion, Otto, 2012 Solo and Visa, Otto 2011 Faced with the challenges presented by digital media and During his MA studies in Illustration at Kingston University its inherent ‘non-reality’, Otto believes in the continued in 1996 he discovered screenprinting. -

This World & Nearer Ones Nyc's First

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE MEDIA CONTACT Nicholas Weist, Creative Time [email protected] 212.206.6674 x 205 CREATIVE TIME PRESENTS PLOT09: THIS WORLD & NEARER ONES NYC’S FIRST PUBLIC ART QUADRENNIAL, ON GOVERNORS ISLAND, NYC 19 public art commissions by major international artists Free, Opening June 27 Work by Mark Wallinger, Lawrence Weiner, Anthony McCall, Krzysztof Wodiczko, Patti Smith, AA Bronson, and more PLOT09: This World & Nearer Ones Opening June 27 Free and open to the public Fridays 11-4 and Saturdays and Sundays, 12-6 Digital press center: http://creativetime.org/programs/archive/2009/GI/ (May 29, 2009 New York, NY) Creative Time is pleased to announce its new public art quadrennial: PLOT, taking place on historic Governors Island and featuring international artists responding to the island with new, site-responsive artworks. The first edition of PLOT, This World & Nearer Ones, is curated by Mark Beasley. The project is produced in association with Governors Island Preservation and Education Corporation, the National Park Service, NYC & Company, and the Office of the Mayor. PLOT09 will draw thousands to Governors Island to explore the artwork and numerous other public programs. PLOT09 is free and open to the public, and will open on June 27. This World & Nearer Ones will intervene in the architectural and natural fabric of the island, transforming its historic buildings and vast lawns—from the iconic Fort Jay to St. Cornelius Chapel—through installation, performance, video, and auditory works, inviting audiences to reconsider the island’s past and future. PLOT09 will feature artists from 9 different countries, including Edgar Arceneaux, AA Bronson and Peter Hobbs, The Bruce High Quality Foundation, Adam Chodzko, Tue Greenfort, Jill Magid, Teresa Margolles, Anthony McCall, Nils Norman, Susan Philipsz, Patti Smith and Jesse Smith, Tercerunquinto, Tris Vonna-Michell, Mark Wallinger, Klaus Weber, Lawrence Weiner, Judi Werthein, Guido van der Werve, and Krzysztof Wodiczko, realizing temporary projects in various sites throughout Governors Island. -

MAUREEN PALEY. Press Release AA BRONSON + GENERAL IDEA 30 September

MAUREEN PALEY. press release AA BRONSON + GENERAL IDEA 30 September – 11 November 2018 private view: Sunday 30 September 5:30 – 7:30 pm The exhibition marks fifty years since AA Bronson, Felix Partz and Jorge Zontal first met in 1968, initiating their collaboration as the Canadian collective General Idea the following year. Over the course of twenty five years (1969-1994), they lived and worked together to produce the living artwork of their being together, undertaking over 100 solo exhibitions, countless group shows and temporary public art projects. They were known for their magazine FILE (1972-1989), their unrelenting production of numerous multiples, and their early involvement in punk, queer theory and AIDS activism. The celebrated publication FILE appropriated the design of LIFE magazine; some of the most radical artists and collectives of the period contributed to FILE, among them Art & Language, writer William Burroughs, and bands such as Talking Heads and The Residents. The adoption of the existing mass-market format of LIFE magazine set up a sustained interest in the possibility of using ‘found formats’ as ‘hosts’ for their ideas. From 1987 through 1994, working primarily in New York City, General Idea’s work addressed the AIDS crisis and produced their best known work to date - Imagevirus. Reappropriating Robert Indiana’s work LOVE - substituting, in the same visual arrangement and colour composition, the letters L-O-V-E with A-I-D-S – they used the mechanism of viral transmission to investigate the term as both word and image. The series took the form of paintings, sculptures, postage stamps, posters and magazine covers. -

Kelly Rogers Thesis

UNIVERSITY OF OKLAHOMA GRADUATE COLLEGE Post-Digital Publishing Practices in Contemporary Arts Publishing A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE FACULTY In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in Art History By Kelly Rogers Norman, Oklahoma 2019 Post-Digital Publishing Practices in Contemporary Arts Publishing A THESIS APPROVED FOR THE SCHOOL OF VISUAL ARTS BY THE COMMITTEE CONSISTING OF Dr. Robert Bailey, Chair Dr. Alison Fields Dr. Erin Duncan-O’Neill © Copyright by Kelly Rogers 2019 All Rights Reserved. !iv TABLE OF CONTENTS ABSTRACT …………………………………………………………………………… v INTRODUCTION……………………………………………………………………… 1 CHAPTER 1: POST-DIGITAL PUBLISHING……..………………………………….. 12 CHAPTER 2: POST-DIGITAL PUBLISHERS..……………………………………….. 29 CHAPTER 3: POST-DIGITAL PUBLICATIONS…..…………………………………. 43 CONCLUSION…………………………………………………………………………. 54 BIBLIOGRAPHY………………………………………………………………………. 57 APPENDIX………………………………………………………………………………61 !v ABSTRACT A consideration of the ways in which post-digital influence impacts visual culture, and specifically arts publishing. The post-digital moment creates a unique opportunity for analog/digital crossover, which manifests in publishing practices and publications. This thesis aims to dedicate a space for discourse concerning these contemporary practices. Focusing on self-reflexive sources about arts publishing, this study analyzes the hybridization of media, pointing to mediatization as a result of our contemporary moment and its integrated digital influences. I address design and object composition of publications and artistic publishing practices using visual analysis to evaluate the tangible (or non-tangible) aspects of the publication and assess the multidisciplinary reach of arts publishing. This type of analysis supports the ideas of arts publishing as artistic practice, and allows us to develop a literary and aesthetic commentary about contemporary arts publishing and the latest developments in this field. -

BOOK ARTS NEWSLETTER No. 44 September 2008

ISSN 1754-9078 (Print) UWE Bristol, School of Creative Arts, Department of Art and Design ISSN 1754-9086 (Online) BOOK ARTS NEWSLETTER No. 44 September 2008 In this issue: National and International Artists’ Books Exhibitions Pages 1 - 7 Announcements Pages 7 - 8 Courses and Workshops Pages 8 - 9 Artist’s Book Fairs & Festivals Pages 9 - 11 Opportunities Pages 11 - 12 Wanted Page 13 Internet News Page 13 New Artists’ Publications Pages 14 - 16 Reports and Reviews: Wilcannia Wilderness - Julie Barratt’s artist’s book residency Page 17 I am paper Mary Pullen Page 17 Acccordion and Tunnel Books: 20 Years of Exploration Rand Huebsch Pages 17 - 19 Late News page 20 Artists’ Books Exhibitions at Bower Ashton Library My interest over the years lies in exploring what I consider to School of Creative Arts, Department of Art and Design be the special qualities of ‘books’ rather than the familiar University of the West of England, Bristol, UK appearance of them, the way in which a book gradually reveals its contents page by page, detail by detail, or even word by COVER ME IN COWHIDE - UMJETNICKE KNJIGE word, yielding at its own pace its narrative and its potential Andrew Norris 1988 - 2008, Simultaneous 20th Anniversary while engaging the reader in a moment of quiet contemplation. Retrospective Exhibitions of Artists’ Books in City Library of Zagreb, Croatia, and Bower Ashton Library, Bristol, England. Therefore, I consider a stick, with its text spiraling along its length, A Wood Some Trees (2002/2008), a mathematical 8th September - 8th October 2008 construction that twists and turns to meet words with images, River, Rocks and Foliage (1991), or a cow-hide covered frieze of The artists’ books, book-works and book-objects that I have friesian cows, HERD (1993) as falling under the same ‘artist’s been making over the past 20 years have, as a common theme, book’ genre. -

Paul O'neill and Aa Bronson

PAU L O ’ N E I L L A N D AA B R on S on New York, 2004–2006 PAUL: Maybe we could start by tracing the beginning of the history of General Idea? AA: General Idea happened by accident. It was the late ‘60s in Toronto and our friend Mimi (who was Felix Partz’s girlfriend) found this old house, 78 Gerrard Street West, and convinced us to move in together to save rent. There were about eight of us and we were all more or less straight out of school. We moved in to the house, which at one point had been turned into a shop. It was the late ‘60s, the pop era, there were flowers painted on the street, and now the street had more or less died down and the action had moved to some other part of town. We moved into this rather forlorn house, which had a store window punched into the living room; we were all unemployed, mostly artists, and we were a little bored. We began rummaging through the garbage of the various neighboring businesses, and we began to AA Bronson (right) and Mark Krayenhoff (left) assemble fake stores in our store window. We did window Printed Matter, 10th Avenue, New York, NY, 2005 displays essentially. We didn’t think of it as art at the Photo: Paul O’Neill. time, we were just entertaining ourselves. Sometimes the displays got out of hand. We would have to give up are sort of illuminated today in particular ways, but I our living room to them; we did immense displays that won’t get into too many of them.