Scholars Portal PDF Export

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Core 1..104 Hansard (PRISM::Advent3b2 6.50.00)

CANADA House of Commons Debates VOLUME 138 Ï NUMBER 116 Ï 2nd SESSION Ï 37th PARLIAMENT OFFICIAL REPORT (HANSARD) Wednesday, June 11, 2003 Speaker: The Honourable Peter Milliken CONTENTS (Table of Contents appears at back of this issue.) All parliamentary publications are available on the ``Parliamentary Internet Parlementaire´´ at the following address: http://www.parl.gc.ca 7131 HOUSE OF COMMONS Wednesday, June 11, 2003 The House met at 2 p.m. challenged clients received a donation from Sun Country Cable, a donation that will enable the centre to continue its work in our Prayers community. Sun Country Cable donated the building. This building is next to Kindale's existing facility and both properties will eventually lead to construction of a new centre. In the meantime, the Ï (1405) building will be used for training and respite suites. [English] I am proud to be part of a community that looks out for those less The Speaker: As is our practice on Wednesday we will now sing fortunate. Charity does begin at home. O Canada, and we will be led by the hon. member for Winnipeg North Centre. *** [Editor's Note: Members sang the national anthem] [Translation] SOCIÉTÉ RADIO-CANADA STATEMENTS BY MEMBERS Mr. Bernard Patry (Pierrefonds—Dollard, Lib.): Mr. Speaker, I would like to share some of my concerns about the recent decision [English] by Société Radio-Canada to cancel its late evening sports news. CHABAD Hon. Art Eggleton (York Centre, Lib.): Mr. Speaker, I rise to I am worried, because last year this crown corporation had also decided to stop broadcasting the Saturday night hockey games, La pay tribute to Chabad Lubavitch which is the world's largest network Soirée du hockey. -

The Requisites of Leadership in the Modern House of Commons 1

Number 4 November 2001 CANADIAN STUDY OF PARLIAMENT GROUP HE EQUISITES OF EADERSHIP THE REQUISITES OF LEADERSHIP IN THE MODERN HOUSE OF COMMONS Paper by: Cristine de Clercy Department of Political Studies University of Saskatchewan Canadian Members of the Study of Parliament Executive Committee Group 2000-2001 The Canadian Study of President Parliament Group (CSPG) was created Leo Doyle with the object of bringing together all those with an interest in parliamentary Vice-President institutions and the legislative F. Leslie Seidle process, to promote understanding and to contribute to their reform and Past President improvement. Judy Cedar-Wilson The constitution of the Canadian Treasurer Study of Parliament Group makes Antonine Campbell provision for various activities, including the organization of conferences and Secretary seminars in Ottawa and elsewhere in James R. Robertson Canada, the preparation of articles and various publications, the Counsellors establishment of workshops, the Dianne Brydon promotion and organization of public William Cross discussions on parliamentary affairs, David Docherty participation in public affairs programs Jeff Heynen on radio and television, and the Tranquillo Marrocco sponsorship of other educational Louis Massicotte activities. Charles Robert Jennifer Smith Membership is open to all those interested in Canadian legislative institutions. Applications for membership and additional information concerning the Group should be addressed to the Secretariat, Canadian Study of Parliament Group, Box 660, West Block, Ottawa, Ontario, K1A 0A6. Tel: (613) 943-1228, Fax: (613) 995- 5357. INTRODUCTION This is the fourth paper in the Canadian Study of Parliament Groups Parliamentary Perspectives. First launched in 1998, the perspective series is intended as a vehicle for distributing both studies prepared by academics and the reflections of others who have a particular interest in these themes. -

What Happens After an Indecisive Election Result?

BRIEFING PAPER Number 07163, 9 June 2017 What happens after an By Lucinda Maer indecisive election result? Gail Bartlett Inside: 1. Forming a government after a hung parliament 2. “Caretaker” administrations 3. The meeting of a new Parliament 4. The Queen’s Speech 5. An investiture vote? www.parliament.uk/commons-library | intranet.parliament.uk/commons-library | [email protected] | @commonslibrary Number 07163, 9 June 2017 2 Contents Summary 3 1. Forming a government after a hung parliament 5 1.1 What kind of government can form? 5 1.2 Historical precedents 6 1.3 When should an incumbent Prime Minister resign? 7 1.4 How long does government formation take? 9 1.5 Internal party consultation 9 1.6 Role of the House of Commons 10 1.7 Effects of the Fixed-term Parliaments Act 2011 10 2. “Caretaker” administrations 12 2.1 What is a “caretaker” administration? 12 2.2 The nature of the restrictions on government action 12 2.3 When do the restrictions end? 13 3. The meeting of a new Parliament 15 3.1 When does a Parliament return? 15 4. The Queen’s Speech 17 4.1 When does the Queen’s Speech take place? 17 4.2 The debate on the Address 17 5. An investiture vote? 19 Cover page image copyright UK Parliament 3 What happens after an indecisive election result? Summary Following the 2017 general election, held on 8 June 2017, the Conservative Party was returned as the largest party, but did not have an overall majority in the House of Commons. -

Twentieth-Century Canadian Law, Psychiatry, and Social Activism in Relation to Pedophiles and Child Sex Offenders

Twentieth-Century Canadian Law, Psychiatry, and Social Activism in Relation to Pedophiles and Child Sex Offenders By Justin F. Smith Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the MA degree in History University of Ottawa © Justin F. Smith, Ottawa, Canada, 2017 ABSTRACT Twentieth-Century Canadian Law, Psychiatry, and Social Activism in Relation to Pedophiles and Child Sex Offenders Justin Smith Supervisor: University of Ottawa Heather Murray The contemporary conflation of pedophiles and child sex offenders is a prevalent aspect of reporting in news and social media, as well as in government- sponsored efforts to prevent child sexual victimization. Throughout twentieth century Canada, however, legal experts, psychologists and psychiatrists, and social activists were recognizing the harmfulness of grouping individuals who may have a propensity to commit crime with those who have committed the most heinous of criminal acts. As early as 1938, Canadian legal experts suggested that criminal insanity was a myth, advocating for a divergence between legal punishment and psychiatric healthcare, but after World War 2 had enacted serious efforts targeting criminal sexual psychopathy. Successive Royal Commissions investigating sexual victimization and child abuse revealed that Canadian courts, jails, prisons, and remand services were unable to solely deal with the realities of child sexual victimization. Psychologists and psychiatrists of the American Psychological Association increasingly researched sex and sexuality, classifying pedophilia as a paraphilia using child sexual victimization as a diagnostic indicator and criterion. Gay liberation activists discussed inequalities posed between hetero- and homosexual ages of consent and, more rarely, thought about the total abolition of age of consent. -

Spring Convocation 2005 Saskatoon Centennial Auditorium

2005 May 25 & 26 Spring Convocation 2005 Saskatoon Centennial Auditorium Ceremony 1, Wednesday May 25, 9:00 a.m. ............................. page 17 Undergraduate degrees, graduate degrees, diplomas and certifi cates will be awarded for Arts & Science. Ceremony 2, Wednesday May 25, 2:00 p.m. ............................. page 47 Undergraduate degrees, graduate degrees and diplomas will be awarded for Agriculture, Commerce and Engineering. Ceremony 3, Thursday May 26, 9:00 a.m. ............................... page 65 Undergraduate degrees, graduate degrees and diplomas will be awarded for Dentistry, Kinesiology, Medicine, Nursing, Pharmacy & Nutrition, Physical Therapy and Veterinary Medicine. Ceremony 4, Thursday May 26, 2:00 p.m. ............................... page 83 Undergraduate degrees, graduate degrees and diplomas will be awarded for Education and Law. University of Saskatchewan 1 2005 Spring Convocation A message from President Peter MacKinnon want to express a very warm welcome to the graduates, families and friends who join us today. Convocation is the University’s most important Iceremony, for it is here that we celebrate the accomplishments of our students and the contributions of their loved ones to their success. You should be proud of this day, and of the commitment and sacrifi ce that it represents. We at the University of Saskatchewan salute you—our graduates—and we extend to you our very best wishes for the future. We hope that you will stay in touch with us through our University of Saskatchewan alumni family, and that we will have the opportunity to welcome you ‘home’ to our campus many times in the years ahead. Warmest congratulations! University of Saskatchewan 3 2005 Spring Convocation University of Saskatchewan 2005 Spring Convocation he word “Convocation” arises from the Latin “con” T meaning “together,” and “vocare” meaning “to call.” Our Convocation ceremony is a calling together of the new graduates of the University of Saskatchewan, symbolizing the historical practice of calling together all former graduates. -

Alternative North Americas: What Canada and The

ALTERNATIVE NORTH AMERICAS What Canada and the United States Can Learn from Each Other David T. Jones ALTERNATIVE NORTH AMERICAS Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars One Woodrow Wilson Plaza 1300 Pennsylvania Avenue NW Washington, D.C. 20004 Copyright © 2014 by David T. Jones All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, scanned, or distributed in any printed or electronic form without permission. Please do not participate in or encourage piracy of copyrighted materials in violation of author’s rights. Published online. ISBN: 978-1-938027-36-9 DEDICATION Once more for Teresa The be and end of it all A Journey of Ten Thousand Years Begins with a Single Day (Forever Tandem) TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction .................................................................................................................1 Chapter 1 Borders—Open Borders and Closing Threats .......................................... 12 Chapter 2 Unsettled Boundaries—That Not Yet Settled Border ................................ 24 Chapter 3 Arctic Sovereignty—Arctic Antics ............................................................. 45 Chapter 4 Immigrants and Refugees .........................................................................54 Chapter 5 Crime and (Lack of) Punishment .............................................................. 78 Chapter 6 Human Rights and Wrongs .................................................................... 102 Chapter 7 Language and Discord .......................................................................... -

CONTENTS Trust in Government

QUESTIONS – Tuesday 15 August 2017 CONTENTS Trust in Government ................................................................................................................................ 367 Jobs – Investment in the Northern Territory ............................................................................................ 367 NT News Article ....................................................................................................................................... 368 Same-Sex Marriage Plebiscite ................................................................................................................ 369 Police Outside Bottle Shops .................................................................................................................... 369 SUPPLEMENTARY QUESTION ................................................................................................................. 370 Police Outside Bottle Shops .................................................................................................................... 370 Moody’s Credit Outlook ........................................................................................................................... 370 Indigenous Employment .......................................................................................................................... 371 Alcohol-Related Harm Costs ................................................................................................................... 372 Correctional Industries ............................................................................................................................ -

The 2003 Relaunch of Vancouver Magazine

The 2003 Relaunch of Vancouver Magazine by Matthew O’Grady BComm, Queen’s University, 1998 A PROJECT REPORT SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF PUBLISHING in the Master of Publishing Program Matthew O’Grady 2003 SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY April 2003 All rights reserved. This work may not be reproduced in whole or in part, by photocopy or other means, without permission of the author. APPROVAL Name: Matthew O’Grady Degree: Master of Publishing Title of Project Report: The 2003 Relaunch of Vancouver Magazine Supervisory Committee: ________________________________ Dr. Valerie Frith Senior Supervisor Assistant Professor, Master of Publishing Program Simon Fraser University ________________________________ Dr. Rowland Lorimer Director, Master of Publishing Program Simon Fraser University ________________________________ Mr. Jim Sutherland Editorial Director Transcontinental Media West Date Approved: ________________________________ ii ABSTRACT This project report examines the 2003 relaunch of Vancouver magazine. It provides an overview of the magazine’s 35-year history, as well as an analysis of its current state: editorial, advertising, circulation, readership and competition. The report also offers an inside account of the strategic planning that went into the relaunch, including: findings from a July 2002 competitive analysis of Toronto Life, Canada’s preeminent city magazine; highlights from a November 2002 Vancouver magazine subscriber survey; and a chronicle of various planning meetings, held within Transcontinental Media West, between July and December 2002. This report evaluates Vancouver magazine’s prospects for a successful relaunch within the framework of the two city magazine studies, each of which addresses the role and purpose of a city magazine. Questions and findings from those studies are then posed to three editors of Vancouver magazine (past and present), who offer an analysis of the city magazine research within the context of their specific experiences at the magazine. -

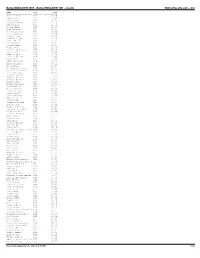

Bolderboulder 2005 - Bolderboulder 10K - Results Onlineraceresults.Com

BolderBOULDER 2005 - BolderBOULDER 10K - results OnlineRaceResults.com NAME DIV TIME ---------------------- ------- ----------- Michael Aish M28 30:29 Jesus Solis M21 30:45 Nelson Laux M26 30:58 Kristian Agnew M32 31:10 Art Seimers M32 31:51 Joshua Glaab M22 31:56 Paul DiGrappa M24 32:14 Aaron Carrizales M27 32:23 Greg Augspurger M27 32:26 Colby Wissel M20 32:36 Luke Garringer M22 32:39 John McGuire M18 32:42 Kris Gemmell M27 32:44 Jason Robbie M28 32:47 Jordan Jones M23 32:51 Carl David Kinney M23 32:51 Scott Goff M28 32:55 Adam Bergquist M26 32:59 trent r morrell M35 33:02 Peter Vail M30 33:06 JOHN HONERKAMP M29 33:10 Bucky Schafer M23 33:12 Jason Hill M26 33:15 Avi Bershof Kramer M23 33:17 Seth James DeMoor M19 33:20 Tate Behning M23 33:22 Brandon Jessop M26 33:23 Gregory Winter M26 33:25 Chester G Kurtz M30 33:27 Aaron Clark M18 33:28 Kevin Gallagher M25 33:30 Dan Ferguson M23 33:34 James Johnson M36 33:38 Drew Tonniges M21 33:41 Peter Remien M25 33:45 Lance Denning M43 33:48 Matt Hill M24 33:51 Jason Holt M18 33:54 David Liebowitz M28 33:57 John Peeters M26 34:01 Humberto Zelaya M30 34:05 Craig A. Greenslit M35 34:08 Galen Burrell M25 34:09 Darren De Reuck M40 34:11 Grant Scott M22 34:12 Mike Callor M26 34:14 Ryan Price M27 34:15 Cameron Widoff M35 34:16 John Tribbia M23 34:18 Rob Gilbert M39 34:19 Matthew Douglas Kascak M24 34:21 J.D. -

Liberals in Coalition

For the study of Liberal, SDP and Issue 72 / Autumn 2011 / £10.00 Liberal Democrat history Journal of LiberalHI ST O R Y Liberals in coalition Vernon Bogdanor Riding the tiger The Liberal experience of coalition government Ian Cawood A ‘distinction without a difference’? Liberal Unionists and Conservatives Kenneth O. Morgan Liberals in coalition, 1916–1922 David Dutton Liberalism and the National Government, 1931–1940 Matt Cole ‘Be careful what you wish for’ Lessons of the Lib–Lab Pact Liberal Democrat History Group 2 Journal of Liberal History 72 Autumn 2011 new book from tHe History Group for details, see back page Journal of Liberal History issue 72: Autumn 2011 The Journal of Liberal History is published quarterly by the Liberal Democrat History Group. ISSN 1479-9642 Riding the tiger: the Liberal experience of 4 Editor: Duncan Brack coalition government Deputy Editor: Tom Kiehl Assistant Editor: Siobhan Vitelli Vernon Bogdanor introduces this special issue of the Journal Biographies Editor: Robert Ingham Reviews Editor: Dr Eugenio Biagini Coalition before 1886 10 Contributing Editors: Graham Lippiatt, Tony Little, York Membery Whigs, Peelites and Liberals: Angus Hawkins examines coalitions before 1886 Patrons A ‘distinction without a difference’? 14 Dr Eugenio Biagini; Professor Michael Freeden; Ian Cawood analyses how the Liberal Unionists maintained a distinctive Professor John Vincent identity from their Conservative allies, until coalition in 1895 Editorial Board The coalition of 1915–1916 26 Dr Malcolm Baines; Dr Roy Douglas; Dr Barry Doyle; Prelude to disaster: Ian Packer examines the Asquith coalition of 1915–16, Dr David Dutton; Prof. David Gowland; Prof. Richard which brought to an end the last solely Liberal government Grayson; Dr Michael Hart; Peter Hellyer; Dr J. -

Table of Contents

TABLE OF CONTENTS THE CHRETIEN LEGACY Introduction .................................................. i The Chr6tien Legacy R eg W hitaker ........................................... 1 Jean Chr6tien's Quebec Legacy: Coasting Then Stickhandling Hard Robert Y oung .......................................... 31 The Urban Legacy of Jean Chr6tien Caroline Andrew ....................................... 53 Chr6tien and North America: Between Integration and Autonomy Christina Gabriel and Laura Macdonald ..................... 71 Jean Chr6tien's Continental Legacy: From Commitment to Confusion Stephen Clarkson and Erick Lachapelle ..................... 93 A Passive Internationalist: Jean Chr6tien and Canadian Foreign Policy Tom K eating ......................................... 115 Prime Minister Jean Chr6tien's Immigration Legacy: Continuity and Transformation Yasmeen Abu-Laban ................................... 133 Renewing the Relationship With Aboriginal Peoples? M ichael M urphy ....................................... 151 The Chr~tien Legacy and Women: Changing Policy Priorities With Little Cause for Celebration Alexandra Dobrowolsky ................................ 171 Le Petit Vision, Les Grands Decisions: Chr~tien's Paradoxical Record in Social Policy M ichael J. Prince ...................................... 199 The Chr~tien Non-Legacy: The Federal Role in Health Care Ten Years On ... 1993-2003 Gerard W . Boychuk .................................... 221 The Chr~tien Ethics Legacy Ian G reene .......................................... -

1976-77-Annual-Report.Pdf

TheCanada Council Members Michelle Tisseyre Elizabeth Yeigh Gertrude Laing John James MacDonaId Audrey Thomas Mavor Moore (Chairman) (resigned March 21, (until September 1976) (Member of the Michel Bélanger 1977) Gilles Tremblay Council) (Vice-Chairman) Eric McLean Anna Wyman Robert Rivard Nini Baird Mavor Moore (until September 1976) (Member of the David Owen Carrigan Roland Parenteau Rudy Wiebe Council) (from May 26,1977) Paul B. Park John Wood Dorothy Corrigan John C. Parkin Advisory Academic Pane1 Guita Falardeau Christopher Pratt Milan V. Dimic Claude Lévesque John W. Grace Robert Rivard (Chairman) Robert Law McDougall Marjorie Johnston Thomas Symons Richard Salisbury Romain Paquette Douglas T. Kenny Norman Ward (Vice-Chairman) James Russell Eva Kushner Ronald J. Burke Laurent Santerre Investment Committee Jean Burnet Edward F. Sheffield Frank E. Case Allan Hockin William H. R. Charles Mary J. Wright (Chairman) Gertrude Laing J. C. Courtney Douglas T. Kenny Michel Bélanger Raymond Primeau Louise Dechêne (Member of the Gérard Dion Council) Advisory Arts Pane1 Harry C. Eastman Eva Kushner Robert Creech John Hirsch John E. Flint (Member of the (Chairman) (until September 1976) Jack Graham Council) Albert Millaire Gary Karr Renée Legris (Vice-Chairman) Jean-Pierre Lefebvre Executive Committee for the Bruno Bobak Jacqueline Lemieux- Canadian Commission for Unesco (until September 1976) Lope2 John Boyle Phyllis Mailing L. H. Cragg Napoléon LeBlanc Jacques Brault Ray Michal (Chairman) Paul B. Park Roch Carrier John Neville Vianney Décarie Lucien Perras Joe Fafard Michael Ondaatje (Vice-Chairman) John Roberts Bruce Ferguson P. K. Page Jacques Asselin Céline Saint-Pierre Suzanne Garceau Richard Rutherford Paul Bélanger Charles Lussier (until August 1976) Michael Snow Bert E.