John Addington Symonds. a Problem in Greek Ethics . Plutarch's Eroticus

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Loeb Lucian Vol5.Pdf

THE LOEB CLASSICAL LIBRARY FOUNDED BY JAMES LOEB, LL.D. EDITED BY fT. E. PAGE, C.H., LITT.D. litt.d. tE. CAPPS, PH.D., LL.D. tW. H. D. ROUSE, f.e.hist.soc. L. A. POST, L.H.D. E. H. WARMINGTON, m.a., LUCIAN V •^ LUCIAN WITH AN ENGLISH TRANSLATION BY A. M. HARMON OK YALE UNIVERSITY IN EIGHT VOLUMES V LONDON WILLIAM HEINEMANN LTD CAMBRIDGE, MASSACHUSETTS HARVARD UNIVERSITY PRESS MOMLXII f /. ! n ^1 First printed 1936 Reprinted 1955, 1962 Printed in Great Britain CONTENTS PAGE LIST OF LTTCIAN'S WORKS vii PREFATOEY NOTE xi THE PASSING OF PEBEORiNUS (Peregrinus) .... 1 THE RUNAWAYS {FugiUvt) 53 TOXARis, OR FRIENDSHIP (ToxaHs vd amiciHa) . 101 THE DANCE {Saltalio) 209 • LEXiPHANES (Lexiphanes) 291 THE EUNUCH (Eunuchiis) 329 ASTROLOGY {Astrologio) 347 THE MISTAKEN CRITIC {Pseudologista) 371 THE PARLIAMENT OF THE GODS {Deorutti concilhim) . 417 THE TYRANNICIDE (Tyrannicidj,) 443 DISOWNED (Abdicatvs) 475 INDEX 527 —A LIST OF LUCIAN'S WORKS SHOWING THEIR DIVISION INTO VOLUMES IN THIS EDITION Volume I Phalaris I and II—Hippias or the Bath—Dionysus Heracles—Amber or The Swans—The Fly—Nigrinus Demonax—The Hall—My Native Land—Octogenarians— True Story I and II—Slander—The Consonants at Law—The Carousal or The Lapiths. Volume II The Downward Journey or The Tyrant—Zeus Catechized —Zeus Rants—The Dream or The Cock—Prometheus—* Icaromenippus or The Sky-man—Timon or The Misanthrope —Charon or The Inspector—Philosophies for Sale. Volume HI The Dead Come to Life or The Fisherman—The Double Indictment or Trials by Jury—On Sacrifices—The Ignorant Book Collector—The Dream or Lucian's Career—The Parasite —The Lover of Lies—The Judgement of the Goddesses—On Salaried Posts in Great Houses. -

Beyond Priesthood Religionsgeschichtliche Versuche Und Vorarbeiten

Beyond Priesthood Religionsgeschichtliche Versuche und Vorarbeiten Herausgegeben von Jörg Rüpke und Christoph Uehlinger Band 66 Beyond Priesthood Religious Entrepreneurs and Innovators in the Roman Empire Edited by Richard L. Gordon, Georgia Petridou, and Jörg Rüpke ISBN 978-3-11-044701-9 e-ISBN (PDF) 978-3-11-044818-4 e-ISBN (EPUB) 978-3-11-044764-4 ISSN 0939-2580 This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 License. For details go to http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data A CIP catalog record for this book has been applied for at the Library of Congress. Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data are available on the Internet at http://dnb.dnb.de. © 2017 Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston Printing and binding: CPI books GmbH, Leck ♾ Printed on acid-free paper Printed in Germany www.degruyter.com TableofContents Acknowledgements VII Bibliographical Note IX List of Illustrations XI Notes on the Contributors 1 Introduction 5 Part I: Innovation: Forms and Limits Jörg Rüpke and FedericoSantangelo Public priests and religious innovation in imperial Rome 15 Jan N. Bremmer Lucian on Peregrinus and Alexander of Abonuteichos: Asceptical viewoftwo religious entrepreneurs 49 Nicola Denzey Lewis Lived Religion amongsecond-century ‘Gnostic hieratic specialists’ 79 AnneMarie Luijendijk On and beyond -

Ethics: Subjectivity and Truth / by Michel Foucault; Edited by Paul Rabinow; Translated by Robert Hurley and Others

THE ESSENTIAL WORKS OF MICHEL FOUCAULT 1954-1984 PAUL RABINOW SERIES EDITOR Ethics, Edited by Paul Rabinow MICHEL FOUCAULT ETHICS SUBJECTIVITY AND TRUTH Ediled by PAUL RABINOW Translated by ROBERT HURLEY AND OTHERS THE ESSENTIAL WORKS OF MICHEL FOUCAULT 1954-1984 VOLUME ONE THE NEW PRESS NEW YORK © 1994 by Editions Gallimard. Compilation, introduction, and new translations © 1997 by The New Press. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, in any form, without written permission from the publisher. The publisher is grateful for pennission to reprint the following copyrighted material: English translations of "Friendship as a Way of Ufe" and "The Ethic of the Concern for the Self as a Practice of Freedom" reprinted from Foucault Live: fnteroiews 1961-1984, Lotringer, ed. (New York, Autonomedia, Ig89), by pennission. English translations of "Sexual Choice, Sexual Act" and "The Masked Philosopher" reprinted from Michel Foucault: Politics, Philosophy, Culture, Lawrence D. Katzman, ed. (1988), by permission of the publisher, Routledge, New York and London. "Sex, Power and the Politics of Identity" reprinted from The Advocate no. 400, August 7, 1984, by permission. "Sexuality and Solitude" reprinted from the London Review of Books, vol. Ill, no. g, May !2:1-June 5, 1981. English translation of "The Battle for Chastity" reprinted from Western Sexuality, Aries, Bejin, eds., with permission from the publisher, Blackwell Publishers. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Foucault, Michel. [Selections. English. 1997l Ethics: subjectivity and truth / by Michel Foucault; edited by Paul Rabinow; translated by Robert Hurley and others. p. cm.-(The essential works of Michel Foucault, 1954-1984; v. -

Loeb Lucian Vol3.Pdf

UJ THE LOEB CLASSICAL LIBRARY FOUNDED BY JAMES LOEB, IX.D. EDITED BY t T. E. PAGE, C.H., LITT.D. fE. CAPPS, PH.D., LL.D. tW.H. D. ROUSE, LITT.D. L. A. POST, L.H.D. E. H. WARMINGTON, M.A., F.R.HIST.SOO. I.UCIAN m LUCIAN WITH AN ENGLISH TRANSLATION BY A. M. HARMON OF YALE UNIVERSITY IN EIGHT VOLUMES III LONDON WILLIAM HEINEMANN LTD CAMBRIDGE, MASSACHUSETTS HARVARD UNIVERSITY PRESS MCMLX First printed 1921 Reprinted 1947, 1960 PRINTED IN GREAT BRITAIN CONTENTS PAGE LIST OF LUCIAN'S WORKS vi THE DEAD COME TO LIFE, OB THE FISHERMAN {Bevivescentes sive Picator) 1 THE DOUBLE INDICTMENT, OR TRIALS BY JURY {Bis Accusatus sive Trihunalia) 83 ON SACRIFICES {De Sacrificus) . 153 THE IGNORANT BOOK-COLLECTOR {Adversus Indoctum et libros mnltos emeniem) 173 THE DREAM, OR LUCIAN's CAREER {Somnium sivB Vita Luciani) 213 THE PARASITE, PARASITIC AN ART [De Parasito sive Ariem esse Parasiticam) 235 » THE LOVER OF LIES, OR THE DOUBTER {PhUopseudes sive Incredulus) 319 THE JUDGEMENT OF THE GODDESSES {Deariim ludiciuvt [Deorum Dialogi ZZ]) 383 ON SALARIED POSTS IN GREAT HOUSES {De Mercede conductis potentium familiaribus) 411 INDEX 483 LIST OF LUCIAN'S WOEKS SHOWING THEIR DIVISION INTO VOLUMES IN THIS EDITION VOLTJME I Phalaris I and II—Hippias or the Bath—Dionysus—Heracles—Amber or The Swans—The Fly—Nigrinus—Demonax—The Hall—My Native Land— Octogenarians—A True Story I and 11—Slander—The Consonants at Law—The Carousal or The Lapiths. VOLUMB II The Downward Joiu-ney or The Tyrant—Zeus Catechized—Zeus Rants —The Dream or The Cock—Prometheus—Icaromenippus or The Sky-man —Timon or The Misanthroi)e—Charon or the Inspector—Philosophies for Sale. -

Virtues for the People Aspects of Plutarchan Ethics PLUTARCHEA HYPOMNEMATA

virtues for the people aspects of plutarchan ethics PLUTARCHEA HYPOMNEMATA Editorial Board Jan Opsomer (K.U.Leuven) Geert Roskam (K.U.Leuven) Frances Titchener (Utah State University, Logan) Luc Van der Stockt (K.U.Leuven) Advisory Board F. Alesse (ILIESI-CNR, Roma) M. Beck (University of South Carolina, Columbia) J. Beneker (University of Wisconsin, Madison) H.-G. Ingenkamp (Universität Bonn) A.G. Nikolaidis (University of Crete, Rethymno) Chr. Pelling (Christ Church, Oxford) A. Pérez Jiménez (Universidad de Málaga) Th. Schmidt (Université de Fribourg) P.A. Stadter (University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill) VIRTUES FOR THE PEOPLE ASPECTS OF PLUTARCHAN ETHICS Edited by GEERT ROSKAM and LUC VAN DER STOCKT Leuven University Press © 2011 Leuven University Press / Presses Universitaires de Louvain / Universitaire Pers Leuven. Minderbroedersstraat 4, B-3000 Leuven (Belgium) All rights reserved. Except in those cases expressly determined by law, no part of this publication may be multiplied, saved in an automated datafile or made public in any way whatsoever without the express prior written consent of the publishers. ISBN 978 90 5867 858 4 D/2011/1869/3 NUR: 735-732 Design cover: Joke Klaassen Contents Efficiency and Effectiveness of Plutarch’s Broadcasting Ethics 7 G. Roskam – L. Van der Stockt 1. Virtues for the people Semper duo, numquam tres? Plutarch’s Popularphilosophie on Friendship and Virtue in On having many friends 19 L. Van der Stockt What is Popular about Plutarch’s ‘Popular Philosophy’? 41 Chr. Pelling Plutarch’s Lives and the Critical Reader 59 T.E. Duff Greek Poleis and the Roman Empire: Nature and Features of Political Virtues in an Autocratic System 83 P. -

Undergraduate Reading List Department of Classics Approved

Undergraduate Reading List Department of Classics Approved by the Department 30 October 2006 Corrected April 13, 2011 Ancient Greek Homer Iliad 1, 6, 9; Odyssey 4, 9 In English: Iliad and Odyssey (all) Homeric Hymns Demeter in Greek In English: Aphrodite, Apollo, and Hermes Hesiod Works and Days 1-247; Theogony 1-232 In English: Works and Days, Theogony (all) Archilochus 1, 2, 3, 6, 22, 74 In English: all selections in A. Miller, Greek Lyric Sappho 1, 16, 31, 44 In English: all selections in A. Miller, Greek Lyric Solon 1 and 24 In English: all selections in A. Miller, Greek Lyric Simonides 542, 121D, 92D In English: all selections in A. Miller, Greek Lyric Bacchylides 3 and 18 In English: all selections in A. Miller, Greek Lyric Pindar Ol. 1 In English: selections of Odes in A. Miller, Greek Lyric: Olympian 2, 12, 13, 14, Pythian 1, 3, 8, 10, Nemean 5, 10, Isthmian 5, 6, 7 Aeschylus Eumenides; In English: Oresteia Sophocles Oedipus Rex In English: Ajax, Antigone, and Oedipus at Colonus Euripides Medea In English: Hippolytus and Bacchae Aristophanes Clouds In English: Frogs, Birds, Lysistrata Herodotus 1.1-92 In English: 6-9 Thucydides 2.1-65; In English: 1, the rest of 2, 6, and 7 Plato Republic I, Ion, Crito In English: Republic, Apology, Symposium Aristotle EN I In English: Poetics (all) Lysias 1 In English: 12 Demosthenes First Philippic Apollonius Argonautica selections in N. Hopkinson, A Hellenistic Anthology: 1.536-58, 1.1153-71, 3.744-824, 4.1629-88 In English: Argonautica (all) Callimachus Selections in N. -

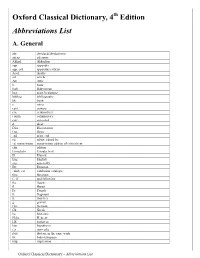

Abbreviations List A

Oxford Classical Dictionary, 4th Edition Abbreviations List A. General abr. abridged/abridgement adesp. adespota Akkad. Akkadian app. appendix app. crit. apparatus criticus Aeol. Aeolic art. article Att. Attic b. born Bab. Babylonian beg. at/nr. beginning bibliog. bibliography bk. book c. circa cent. century cm. centimetre/s comm. commentary corr. corrected d. died Diss. Dissertation Dor. Doric end at/nr. end ed. editor, edited by ed. maior/minor major/minor edition of critical text edn. edition Einzelschr. Einzelschrift El. Elamite Eng. English esp. especially Etr. Etruscan exhib. cat. exhibition catalogue fem. feminine f., ff. and following fig. figure fl. floruit Fr. French fr. fragment ft. foot/feet g. gram/s Ger. German Gk. Greek ha. hectare/s Hebr. Hebrew HS sesterces hyp. hypothesis i.a. inter alia ibid. ibidem, in the same work IE Indo-European imp. impression Oxford Classical Dictionary – Abbreviations List in. inch/es introd. introduction Ion. Ionic It. Italian kg. kilogram/s km. kilometre/s lb. pound/s l., ll. line, lines lit. literally lt. litre/s L. Linnaeus Lat. Latin m. metre/s masc. masculine mi. mile/s ml. millilitre/s mod. modern MS(S) manuscript(s) Mt. Mount n., nn. note, notes n.d. no date neut. neuter no. number ns new series NT New Testament OE Old English Ol. Olympiad ON Old Norse OP Old Persian orig. original (e.g. Ger./Fr. orig. [edn.]) OT Old Testament oz. ounce/s p.a. per annum PIE Proto-Indo-European pl. plate plur. plural pref. preface Proc. Proceedings prol. prologue ps.- pseudo- Pt. part ref. reference repr. -

Elysium: a Sacred Space of Culture

Elysium: A Sacred Space of Culture Gleb von Rims Not everyone is aware that the European Union has its own official anthem – Beethoven’s famous ‘Ode to Joy’, based on Schiller’s lyrics. In the leitmotif sounds the Greek–Latin word Elysium : Freude, schöner Götterfunken, Tochter aus Elysium! Spark from the fire that Gods have fed – Joy – thou Elysian child divine… In other words Elysium is the origin of our ‘joy’. What does Schiller mean by this? Let us recall what this word, Elysium – central to the anthem – really stands for. e first mention of Elysium is in Homer’s Odyssey where one of the characters is promised that the gods will send him to the Elysian Fields. A ‘newly born soul’ went across the river Styx: ‘Beyond the river, the soul is on her own … With proud stance and wide steps, she goes upon the smooth meadow of asphodel, in joy ... e souls of the other famous dead approach to greet her.’[1] According to Hesiod (VIIIth century BC), the indwelling of the Great was located somewhere far towards the West, beyond the Ocean, on the Isles of the Blessed. Hesiod points out that the Great do not go there a~er death, but somehow avoid death altogether, ‘continuing life’.[2] We learn from Pindar (c. 520–432 BC) that even there they retain their physical appearance, the expression of their eyes, their voice and their habits. ey even keep their clothing and continue to do whatever they best loved in life, be it vaulting or composing poetry.[3] Socrates, while discussing the immortality of the soul just before he took hemlock, supposed that he would soon meet the great men of antiquity. -

Loeb Brochure Design

LOEB CLASSICAL LIBRARY 2012 Founded by JAMES LOEB 1911 Edited by JEFFREY HENDERSON NEW TITLES PLATO HIPPOCRATES Republic, Volume I: Books 1 –5 Volume X. Generation. Nature of the Child. Republic, Volume II: Books 6 –10 Diseases 4. Nature of Women and Barrenness ITED AND TRANSLATED BY UL TTER EDITED AND TRANSLATED BY ED PA PO CHRIS EMLYN -J ONES AND This is the tenth volume in the Loeb Classical WILLIAM PREDDY Library’s ongoing edition of Hippocrates’ invaluable Plato of Athens, who laid the foundations of the texts, which provide essential information about the Western philosophical tradition and in range and practice of medicine in antiquity and about Greek depth ranks among its greatest practitioners, was theories concerning the human body. Here, Paul born to a prosperous and politically active family Potter presents the Greek text with facing English ca. 427 BC . In early life an admirer of Socrates, Plato translation of five treatises, four concerning human later founded the first institution of higher learning in reproduction ( Generation , Nature of the Child ) the West, the Academy, among whose many notable and reproductive disorders ( Nature of Women , alumni was Aristotle. Traditionally ascribed to Plato Barrenness ), and one ( Diseases 4 ) that expounds are thirty-six dialogues developing Socrates’ dialectic a general theory of physiology and pathology. method and composed with great sty - All volumes in the listic virtuosity, together with thirteen Loeb Hippocrates letters. Vol. I. Republic , a masterpiece of philosophi - ISBN 978-0-674-99162-0 LCL 147 cal and political thought, concerns Vol. II. righteousness both in individuals and ISBN 978-0-674-99164-4 LCL 148 in communities, and proposes an Vol. -

The End of Carnivalism, Or the Making of the Corpus Lucianeum

Araucaria. Revista Iberoamericana de Filosofía, Política y Humanidades ISSN: 1575-6823 ISSN: 2340-2199 [email protected] Universidad de Sevilla España The End of Carnivalism, or The Making of the Corpus Lucianeum Hafner, Markus The End of Carnivalism, or The Making of the Corpus Lucianeum Araucaria. Revista Iberoamericana de Filosofía, Política y Humanidades, vol. 21, núm. 41, 2019 Universidad de Sevilla, España Disponible en: https://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=28265032010 Esta obra está bajo una Licencia Creative Commons Atribución-NoComercial-SinDerivar 4.0 Internacional. PDF generado a partir de XML-JATS4R por Redalyc Proyecto académico sin fines de lucro, desarrollado bajo la iniciativa de acceso abierto MONOGRÁFICO I e End of Carnivalism, or e Making of the Corpus Lucianeum El fin del carnavalismo o la creación del Corpus Lucianeum Markus Hafner [1] University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Estados Unidos Abstract: In a key passage for the understanding of Lucian’s work, the Fisherman 25– 27, the philosopher Diogenes of Sinope complains that Parrhesiades, a Lucian- like authorial figure, mocks philosophers not within the fixed boundaries of a carnivalesque festival, as Old Comedy used to do, and to which Lucian’s work is otherwise highly indebted, but by means of his constantly published writings. is statement is even more relevant, since the Fisherman belongs to a group of texts which show clear cross-references to other writings within the corpus (such as Essays in Portraiture Defended, Apology, and e Runaways). By creating indirect authorial commentaries Araucaria. Revista Iberoamericana de and intratextual references throughout his œuvre—a hidden (auto)biobibliography, as Filosofía, Política y Humanidades, vol. -

Loeb Lucian Vol7.Pdf

4 I THE LOEB CLASSICAL LIBRARY FOUNDED BY JAMBS LOBB, LL.D. EDITED BY t T. E. PAGE, C.H., LITT.D. t E. CAPPS, PH.D., LL.D. t W. H. D. ROUSE, litt.d. L. A. POST, L.H.D. E. H. WARMINGTON, m.a., f.r.hist.soc. LUGIAN VII LUCIAN WITH AN ENGLISH TRANSLATION BY M.D. MACLEOD LECTURER IN CLASSICS, UNIVERSITY OF SOUTHAMPTON, SOMETIME SCHOLAR OF PEMBROKE COLLEGE, CAMBRIDGE I IN EIGHT VOLUMES VII LONDON WILLIAM HEINEMANN LTD CAMBRIDGE, MASSACHUSETTS HARVARD UNIVERSITY PRESS MOMLXI (g) The President and Fellows of Harvard College 1961 Printed in Great Britain CONTENTS PAGE LIST OF LUCIAN S WORKS vii PBEFACE ix DIAIiOQUES OP THE DEAD . 1 DIALOGUES OF THE SEA-GODS 177 DIALOGUES OF THE GODS . 239 DIALOGUES OF THE COURTESANS 355 INDEX .... 469 LIST OF LUCIAN'S WORKS SHOWING THEIR DIVISION INTO VOLUMES IN THIS EDITION I Volume I Phalaris I and II—Hippias or the Bath—^Dionysufi Heracles—Amber or The Swans—The Fly—Nigrinus— Demonax—The Hall—My Native Land—Octogenarians —A True Story I and II—Slander—The Consonants at Law—The Carousal or The Lapiths. Volume II The Downward Journey or The Tyrant—Zeus Cate- chized—Zeus Rants—^The Dream or The Cock—Prometheus —Icaromenippus or The Sky-man—Timon or The Mis- anthrope—Charon or The Inspector—Philosophies for Sale. Volume III The Dead Come to Life or The Fisherman—The Double Indictment or Trials by Jury—On Sacrifices—The Ignorant Book Collector—The Dream or Lucian's Career—The Parasite—The Lover of Lies—The Judgement of the Goddesses—On Salaried Posts in Great Houses. -

Greece and Platonic Love in E. M. Forster's Maurice, Or the Greatness

Greece and Platonic Love in E. M. Forster’s Maurice, or the greatness and limits of Antiquity as a source of inspiration1 (First part) Pau Gilabert Barberà Universitat de Barcelona (University of Barcelona)2 To Annie Carcedo and in the memory of Patricia Cruzalegui Given a title like this, one might think that this article deals –or will deal- mainly with evidence. I am not going to deny it, since, after all, Forster himself explains in the “Notes on the three men” -who are the protagonists of this novel- that one of them, Clive Durham, shows a “Hellenic temperament”. He is a man who believes in the Platonic way of life and tries at the same time to get his great friend, Maurice, to adopt it as well. I shall not reveal, then, any secret, though I shall try to offer an accurate analysis of something known and “confessed”. It is also true that, in the “Terminal note”, Forster declares himself deeply impressed by Edward Carpenter, a follower of Walt Whitman, and he is convinced of the nobleness of love between comrades. As Forster explains, Carpenter and his friend George Merrill turned into the creative stimulus that made his novel flow smoothly with no impediments. And, nevertheless, it is quite evident that Greece, Plato and his dialogues –mainly his Symposium and Phaedrus- and the Platonic love that thanks to them became fully outlined are the inspiration, the archetype or model, the challenge and, finally, what must be abandoned in order to go beyond it or to guide it towards its true origin.