Summary on the Creation of a System

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Viking Voicejan2014.Pub

Volume 2 February 2014 Viking Voice PENN DELCO SCHOOL DISTRICT Welcome 2014 Northley students have been busy this school year. They have been playing sports, performing in con- certs, writing essays, doing homework and projects, and enjoying life. Many new and exciting events are planned for the 2014 year. Many of us will be watching the Winter Olympics, going to plays and con- certs, volunteering in the community, participating in Reading Across America for Dr. Seuss Night, and welcoming spring. The staff of the Viking Voice wishes everyone a Happy New Year. Northley’s Students are watching Guys and Dolls the 2014 Winter Olympics Northley’s 2014 Musical ARTICLES IN By Vivian Long and Alexis Bingeman THE VIKING V O I C E This year’s winter Olympics will take place in Sochi Russia. This is the This year’s school musical is Guy and • Olympic Events first time in Russia’s history that they Dolls Jr. Guys and Dolls is a funny musical • Guys and Dolls will host the Winter Olympic Games. set in New York in the 40’s centering on Sochi is located in Krasnodar, which is gambling guys and their dolls (their girl • Frozen: a review, a the third largest region of Russia, with friends). Sixth grader, Billy Fisher, is playing survey and excerpt a population of about 400,000. This is Nathan Detroit, a gambling guy who is always • New Words of the located in the south western corner of trying to find a place to run his crap game. Year Russia. The events will be held in two Emma Robinson is playing Adelaide, Na- • Scrambled PSSA different locations. -

Foreign Policy Audit: Ukraine-Latvia

Kateryna Zarembo Elizabete Vizgunova FOREIGN POLICY AUDIT: Ukraine– LATVIA DISCUSSION PAPER Кyiv 2018 The report was produced with the financial support of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Republic of Latvia. The views and opinions expressed in this paper are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Republic of Latvia. Photos: Administration of the President of Ukraine, Verkhovna Rada, Cabinet of Ministers of Ukraine Authors: Kateryna Zarembo, Elizabete Vizgunova CONTENTS 1. Introduction 4 2. Ukraine’s interest in Latvia and Latvia’s interest in Ukraine: points of intersection 7 2.1. Russia’s aggression in Ukraine: impact on Latvia’s Euro-Atlantic identity 7 2.2. Development cooperation: Partner to partner, not teacher to pupil 14 2.3. A common past as a bridge between two countries 19 2.4. Trade and investment: room for improvement 22 3. Who’s who: key stakeholders and pressure groups 25 3.1. Political elites 25 3.2. Latvian civil society and culture space 28 3.3. Media and the information space 32 3.4. The Ukrainian community in Latvia 33 4. Existing and potential risks and conflicts 35 4.1. Change in Latvian policy towards Ukraine after the October 2018 elections 35 4.2. Deterioration in relations over poor business conditions in Ukraine 36 4.3. Susceptibility of public opinion in Latvia to Russian disinformation 37 5. Recommendations 39 6. Acknowledgements 41 3 Foreign Policy Audit: Ukraine-Latvia 1. INTRODUCTION Relations between Ukraine and Latvia make an interesting and a rare example of bilateral relations. -

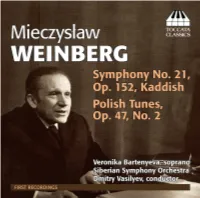

Toccata Classics Cds Are Also Available in the Shops and Can Be Ordered from Our Distributors Around the World, a List of Whom Can Be Found At

Recorded in Omsk Philharmonic Hall, Omsk, Siberia, 28 and 29 May 2013 Recording engineer: Sergei Zhiganov Booklet essay: Philip Spratley Cover photograph: Bernd Moore, Moore Weddings (www.mooreweddings.co.uk) Design and layout: Paul Brooks, Design and Print, Oxford Executive producer: Martin Anderson TOCC 0194 © 2013, Toccata Classics, London P 2013, Toccata Classics, London Come and explore unknown music with us by joining the Toccata Discovery Club. Membership brings you two free CDs, big discounts on all Toccata Classics recordings and Toccata Press books, early ordering on all Toccata releases and a host of other benefits, for a modest annual fee of £20. You start saving as soon as you join. You can sign up online at the Toccata Classics website at www.toccataclassics.com. Toccata Classics CDs are also available in the shops and can be ordered from our distributors around the world, a list of whom can be found at www.toccataclassics.com. If we have no representation in your country, please contact: Toccata Classics, 16 Dalkeith Court, Vincent Street, London SW1P 4HH, UK Tel: +44/0 207 821 5020 E-mail: [email protected] TOCC 0194 Spratley Vol 2.indd 1 25/09/2013 14:12 More British Music PHILIP SPRATLEY ON HIMSELF AND HIS MUSIC on Toccata Classics My early years were spent at Balderton, near Newark, Nottinghamshire, where I was born in 1942. I played the piano as soon as I was big enough to climb on the stool or be helped up by my elder brother, who was a big encouragement. My introduction to music was through the concerts of the TOCC 0088 TOCC 0090 Newark Operatic Society or singing in the choir with my father at St Giles’ Church. -

Season 2012-2013

27 Season 2012-2013 Thursday, December 6, at 8:00 The Philadelphia Orchestra Friday, December 7, at 2:00 Saturday, December 8, Gianandrea Noseda Conductor at 8:00 Denis Matsuev Piano Rachmaninoff Piano Concerto No. 3 in D minor, Op. 30 I. Allegro, ma non tanto II. Intermezzo: Adagio— III. Finale: Alla breve Intermission Rachmaninoff Symphony No. 2 in E minor, Op. 27 I. Largo—Allegro moderato II. Allegro molto III. Adagio IV. Allegro vivace This program runs approximately 2 hours, 10 minutes. These concerts are made possible in cooperation with the Sergei Rachmaninoff Foundation. 3 Story Title 29 The Philadelphia Orchestra Jessica Griffin Renowned for its distinctive vivid world of opera and Orchestra boasts a new sound, beloved for its choral music. partnership with the keen ability to capture the National Centre for the Philadelphia is home and hearts and imaginations Performing Arts in Beijing. the Orchestra nurtures of audiences, and admired The Orchestra annually an important relationship for an unrivaled legacy of performs at Carnegie Hall not only with patrons who “firsts” in music-making, and the Kennedy Center support the main season The Philadelphia Orchestra while also enjoying a at the Kimmel Center for is one of the preeminent three-week residency in the Performing Arts but orchestras in the world. Saratoga Springs, N.Y., and also those who enjoy the a strong partnership with The Philadelphia Orchestra’s other area the Bravo! Vail Valley Music Orchestra has cultivated performances at the Mann Festival. an extraordinary history of Center, Penn’s Landing, artistic leaders in its 112 and other venues. -

Orchestra Filarmonica Di San Pietroburgo Yuri

Orchestra Filarmonica di San Pietroburgo direttore Yuri Temirkanov pianoforte Denis Matsuev 2017 Oltre il rumore del tempo Orchestra Filarmonica di San Pietroburgo direttore Yuri Temirkanov pianoforte Denis Matsuev Palazzo Mauro de André 4 luglio, ore 21 ringrazia Sotto l’Alto Patronato del Presidente della Repubblica Italiana con il patrocinio di Associazione Amici di Ravenna Festival Senato della Repubblica Camera dei Deputati Apt Servizi Emilia Romagna Presidenza del Consiglio dei Ministri Autorità di Sistema Portuale del Mare Adriatico Centro-Settentrionale Ministero dei Beni e delle Attività Culturali e del Turismo BPER Banca Ministero degli Affari Esteri e della Cooperazione Internazionale Cassa dei Risparmi di Forlì e della Romagna Cassa di Risparmio di Ravenna Classica HD Cmc Ravenna con il sostegno di Cna Ravenna Confartigianato Ravenna Confindustria Romagna COOP Alleanza 3.0 Credito Cooperativo Ravennate e Imolese Comune di Ravenna Eni Federazione Cooperative Provincia di Ravenna Federcoop Nullo Baldini Fondazione Cassa dei Risparmi di Forlì Fondazione Cassa di Risparmio di Ravenna Fondazione del Monte di Bologna e Ravenna Gruppo Hera Gruppo Mediaset Publitalia ’80 con il contributo di Hormoz Vasfi ITway Koichi Suzuki Legacoop Romagna Metrò Mezzo Mirabilandia Poderi dal Nespoli PubbliSOLE Publimedia Italia Quotidiano Nazionale Comune di Forlì Comune di Comacchio Comune di Russi Rai Uno Reclam Romagna Acque Società delle Fonti Koichi Suzuki Sapir Hormoz Vasfi Setteserequi Unipol Banca UnipolSai Assicurazioni partner principale -

Toccata Classics TOCC0193 Notes

P MIECZYSŁAW WEINBERG: MEMORIES OF POLAND by David Fanning The last five years of Stalin’s rule were a dark period for Weinberg. Like many of his Soviet fellow-composers he had been stigmatised in the anti-formalism campaign of spring 1948. He was also tailed by the secret police in the aftermath of the murder (also in early 1948, and ordered by Stalin himself) of his father-in-law, the great Jewish actor Solomon Mikhoels. His unfortunate family ties included Miron Vovsi, Mikhoels’ cousin and one of those implicated in the ‘Doctors’ plot’ trumped up by Stalin and his entourage as a result of a toxic mix of paranoia and anti-Semitism. This nexus culminated in Weinberg’s arrest on 7 February 1953 and an eleven-week period of imprisonment in the infamous Lubyanka jail in Moscow. The coping strategy for composers in the aftermath of the anti-formalism campaign involved writing music ‘for the people’, which should ideally be tuneful and based on folk traditions. Here Weinberg was in luck. With part of his family background in Moldavia, his own upbringing in Poland and a Jewish family culture, he had three traditions to draw on: ones that would set his music apart from his peers and that meant all the more to him because of his status as a refugee from Nazi invasions. All three traditions figure prominently in his music from these years. His Sinfonietta No. 1, composed in 1948 on the eve of the ‘anti-cosmopolitan’ (a euphemism for anti-Semitic) crackdown, made extensive use of Jewish idioms. -

Piano Concerto No 2 in C Minor, Op

SU TCERTO N E AON O 2 V M C ONCERTO O C NO N O HESTRA 2 A N RC SI A O IEV P I RG I P Y E V K G V S Y N O E N R I I N I E I F R L E N O A A A K V M M O D R H P C A R 2 RACHMANINOV / PROKOFIEV MARIINSKY SERGEI RACHMANINOV / СЕРГЕЙ РАХМАНИНОВ (1873–1943) Финал, поначалу бодрый и деловой, постепенно вводит более ПРОКОФЬЕВ Piano Concerto No 2 in C minor, Op. 18 (1900–01) / мелодичную вторую тему, в развитии которой, вне всякого ФОРТЕПИАННЫЙ КОНЦЕРТ N 2 Концерт № 2 для фортепиано с оркестром, до-минор, соч. 18 сомнения, вновь возникает возносящаяся вверх тема, которая так важна была в первых двух частях. Именно эту тему и СОЛЬ-МИНОР, СОЧ.16 1 i. Moderato 9’52’’ подхватывает в конце ликующий апофеоз, перед тем, как Дэниэль Джаффе 2 ii. Adagio sostenuto – Più animato – Tempo I 9’53’’ заключительные аккорды пианиста и оркестра завершают концерт. Когда Сергей Прокофьев стал сочинять свой Второй концерт 3 iii. Allegro scherzando 11’21’’ в конце 1912 года, он был еще студентом Петербургской консерватории. Завершив концерт летом следующего года, он SERGEI PROKOFIEV / СЕРГЕЙ ПРОКОФЬЕВ (1891–1953) посвятил его памяти своего близкого друга, молодого пианиста Piano Concerto No 2 in G minor, Op. 16 (1912-13, reconstructed 1923) / С.В. РАХМАНИНОВ (1873–1943) Максимилиана Шмидтгофа. Прокофьев и Шмидтгоф Концерт № 2 для фортепиано с оркестром, соль-минор, соч. 16 Леонид Гаккель познакомились будучи студентами весной 1909 за несколько месяцев до смерти отца Прокофьева, страдавшего чрезвычайно 4 i. -

Denis Matsuev

Denis Matsuev Sunday Afternoon, October 16, 2016 at 4:00 Hill Auditorium Ann Arbor 11th Performance of the 138th Annual Season 138th Annual Choral Union Series PROGRAM Ludwig van Beethoven Piano Sonata No. 31 in A-flat Major, Op. 110 Moderato cantabile molto espressivo Allegro molto Adagio ma non troppo Robert Schumann Symphonic Etudes, Op. 13 Theme: Andante Etude VI: Agitato Etude I: Un poco più vivo Etude VII: Allegro molto Etude II: Marcato il canto Etude VIII: Andante Etude III: Vivace Etude IX: Presto possibile Etude IV: Allegro marcato Etude X: Allegro Etude V: Vivacissimo Etude XI: Andante Posthumous Variation No. 4 Etude XII: Allegro brillante Posthumous Variation No. 5 Intermission Franz Liszt Mephisto Waltz No. 1, S. 514 Piotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky This afternoon’s presenting sponsor is the Masco Corporation Foundation. Méditation, Op. 72, No. 5 This afternoon’s supporting sponsors are Retirement Income Solutions and the Catherine S. Arcure Endowment Fund. Media partnership is provided by WGTE 91.3 FM and WRCJ 90.9 FM. Sergei Prokofiev Piano Sonata No. 7 in B-flat Major, Op. 83 The Steinway piano used in this afternoon’s recital is made possible by William and Mary Palmer. Special thanks to Tom Thompson of Tom Thompson Flowers, Ann Arbor, for his generous contribution of Allegro inquieto floral art for this afternoon’s recital. Andante caloroso Mr. Matsuev gratefully acknowledges The AVC Charity (Andrey Cheglakov, Founder) as a Strategic Precipitato Partner of this afternoon’s performance. Mr. Matsuev appears by arrangement with Columbia Artists Management, Inc. In consideration of the artist and the audience, please refrain from the use of electronic devices during the performance. -

Discours Du Délégué Permanent De La Russie Auprès De L'unesco

Discours du Délégué Permanent de la Russie auprès de l’UNESCO Madame Eleonora Mitrofanova à la cérémonie de nomination en qualité d’Ambassadeur de bonne volonté de l’UNESCO à l’artiste du peuple de Russie Mr. Denis Matsuev (Paris, Siège de l’UNESCO, le 2 avril 2014) Cher Monsieur Denis Matsuev, Chère Madame Irina Bokova, Cher Monsieur Mintimer Chaïmiev, Vos Excellences, Mesdames, Messieurs, Le pianiste Denis Matsuev est un exemple rare de musicien classique reconnu non seulement parmi le petit cercle des connaisseurs de musique classique, mais aussi bien en dehors. Aujourd’hui tous ses concerts sont planifiés plusieurs années à l’avance. Denis Matsuev est l’invité convoité par les plus grandes salles de concert dans le monde entier, le participant immanquable des festivals philharmoniques les plus connus, le partenaire inaltérable des orchestres symphoniques majeurs de Russie, d’Europe, d’Amérique du Nord et des pays d’Asie. Parmi les partenaires de scène de Denis Matsuev il y a des collectifs des Etats Unis, d’Allemagne, de France, de Grande Bretagne, mais aussi l’orchestre du Théatre Mariinsky, l’Orchestre symphonique de Montréal, l’Orchestre du Théâtre La Scala, l’Orchestre national de Belgique et l’Orchestre de chambre Européen, tous mondialement connus. Sibérien d’Irkutsk, géant au physique athlétique de sportif et jeune homme charmant, depuis sa plus tendre enfance Denis a absorbé la force et la puissance naturelle, ainsi que l’unicité de l’admirable site de patrimoine naturel russe, le lac Baïkal, sur les bords duquel est née sa destinée artistique. “Je suis d’origine des bords du lac Baïkal et toute mon énergie provient de là-bas”, confie Denis. -

Kateryna Smagliy

Kateryna Smagliy Research Paper October 2018 Credits The Institute of Modern Russia (IMR) is a public policy think-tank that strives to establish an intellectual frame- work for building a democratic Russia governed by the rule of law. IMR promotes social, economic, and institu- tional development in Russia through research, analysis, advocacy and outreach. Our goal is to advance Russia’s integration into the community of democracies and to improve its cooperation on the global stage. https://imrussia.org Project “Underminers” has been carried out since 2016 by a group of investigative journalists and activists under the auspices of Free Speech LLC, a US-based entity registered in 2013. Project “Underminers” is supported by a non-profit organization Free Russia Foundation, large part of the work is executed on a voluntary basis by mostly Russian-speaking experts that now live in Europe and USA. Our goal is to raise awareness and start debate in the post-Soviet states and among Western audiences on the scale and nature of kleptocratic actors’ action in domestic politics and their corrosive activities in Europe and USA. https://www.underminers.info Author: Kateryna Smagliy Contributor: Ilya Zaslavskiy (chapters 6 and 7) External editing: Peter Dickinson, Ariana Gic, Monika Richter, Roman Sohn Infographics: Roman Sohn Cover design: Marian Luniv Cover photo: The KGB museum in Prague (credit: author) © Kateryna Smagliy © The Institute of Modern Russia © Project “Underminers,” Free Speech LLC ABSTRACT This paper examines the Kremlin’s connections with think tanks, universities, and research institutions in Russia, Europe and the United States and its co-optation of Russian and Western experts into the pool of proxy communicators for the Putin regime. -

Key Facts and Figures on the Russia / Unesco Cooperation

Last update: March 2018 KEY FACTS AND FIGURES ON THE RUSSIA / UNESCO COOPERATION 1. Membership in UNESCO: since 21 April 1954 2. Membership on the Executive Board: yes (2015-2019) Representative: Ambassador Alexander Kuznetsov Previous terms: continuous member since 1954 3. Membership on Intergovernmental Committees, Commissions, etc.: Intergovernmental Council of the International Programme for the Development of Communication (term expires in 2021) Intergovernmental Council for the Information for All Programme (term expires in 2021) Intergovernmental Committee for Physical Education and Sport (term expires in 2021) Special Committee of the Executive Board (SP) (term expires in 2019) Committee on Non-Governmental Partners (NGP) of the Executive Board (term expires in 2019) Committee on Conventions and Recommendations (CR) of the Executive Board (term expires in 2019) International Coordinating Council of the Programme on Man and the Biosphere. Vice-President (term expires in 2019) Intergovernmental Council for the International Hydrological Programme (term expires in 2019) Intergovernmental Council of the "Management of Social Transformations" Programme (term expires in 2019) Intergovernmental Bioethics Committee (term expires in 2019) Intergovernmental Oceanographic Commission. Vice-Presidency Governing Board of the UNESCO Institute for Information Technologies in Education 4. Your visits to the Russian Federation: none 5. The former Director-General’s visits to the Russian Federation: 11 20-22 August 2017: visit to the Republic of Tatarstan 5-8 July 2017: visit to the Sakha Republic on the occasion of the Second International Forum “World Epics on the Land of Olonkho”. Met with Mr Egor Borisov, Head of the Sakha Republic and scientific, educational and cultural representatives. Visited the Lena Pillars Nature Park – a natural World Heritage site since 2012. -

The XIV Summer Ballet Seasons the International Festival of Youth Photo

The IV International Festival of Puppet Theatres of Caspian States “The Caspian coast" 2014-10-01 — 2014-10-06 Arts festivals Region: Astrakhan region City: Astrakhan Venue: Astrakhan State puppet theatre Phone: (8512) 52 40 25 Webpage: astrpupp.ru minkult.astrobl.ru In Astrakhan State puppet theatre presentations of performances will take place both for members of the jury and spectators. This year the festival will be attended by puppet masters from Dagestan, Kalmykia, Azerbaijan, Kazakhstan and Turkmenistan. For the first time the theater group from the Islamic Republic of Iran will come. The puppet theaters from Rostov-on-Don and the Autonomous Republic of Crimea will become the guests of the festival. The main objective of the festival is the creation of international community of artists – puppet masters, introduction of achievements of national cultures, traditional and modern dramaturgy of puppet theatres of Caspian countries to the broad audience. Apart for competition programme, within the framework of theater forum roundtable discussions and meetings with leading experts in the field of puppet theater art as well as excursions are planned. The VI International Festival of Adyg Culture 2014-10-01 — 2014-10-06 Arts festivals Region: Adygea City: Maikop Webpage: мкра.рф Both professional and amateur artists from regions of Russia and countries where Circassian diaspora lives will take part in the festival. Within the framework of the festival the contests of singers, dancers and instrumentalists will be held. The Food Forum of Polar Region 2014-10-02 — 2014-10-05 Exhibitions and forums Region: Murmansk region City: Murmansk Venue: Ice Palace Phone: 8 (8152) 55 11 33 Webpage: www.murmanexpo.ru It is the 8-th specialized exhibition.