Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Janakeeya Hotel Updation 07.09.2020

LUNCH LUNCH LUNCH Home No. of Sl. Rural / No Of Parcel By Sponsored by District Name of the LSGD (CDS) Kitchen Name Kitchen Place Initiative Delivery units No. Urban Members Unit LSGI's (Sept 7th ) (Sept 7th ) (Sept 7th) Janakeeya 1 Alappuzha Ala JANATHA Near CSI church, Kodukulanji Rural 5 32 0 0 Hotel Coir Machine Manufacturing Janakeeya 2 Alappuzha Alappuzha North Ruchikoottu Janakiya Bhakshanasala Urban 4 194 0 15 Company Hotel Janakeeya 3 Alappuzha Alappuzha South Samrudhi janakeeya bhakshanashala Pazhaveedu Urban 5 137 220 0 Hotel Janakeeya 4 Alappuzha Ambalappuzha South Patheyam Amayida Rural 5 0 60 5 Hotel Janakeeya 5 Alappuzha Arattupuzha Hanna catering unit JMS hall,arattupuzha Rural 6 112 0 0 Hotel Janakeeya 6 Alappuzha Arookutty Ruchi Kombanamuri Rural 5 63 12 10 Hotel Janakeeya 7 Alappuzha Bharanikavu Sasneham Janakeeya Hotel Koyickal chantha Rural 5 73 0 0 Hotel Janakeeya 8 Alappuzha Budhanoor sampoorna mooshari parampil building Rural 5 10 0 0 Hotel chengannur market building Janakeeya 9 Alappuzha Chenganoor SRAMADANAM Urban 5 70 0 0 complex Hotel Chennam pallipuram Janakeeya 10 Alappuzha Chennam Pallippuram Friends Rural 3 0 55 0 panchayath Hotel Janakeeya 11 Alappuzha Cheppad Sreebhadra catering unit Choondupalaka junction Rural 3 63 0 0 Hotel Near GOLDEN PALACE Janakeeya 12 Alappuzha Cheriyanad DARSANA Rural 5 110 0 0 AUDITORIUM Hotel Janakeeya 13 Alappuzha Cherthala Municipality NULM canteen Cherthala Municipality Urban 5 90 0 0 Hotel Janakeeya 14 Alappuzha Cherthala Municipality Santwanam Ward 10 Urban 5 212 0 0 Hotel Janakeeya 15 Alappuzha Cherthala South Kashinandana Cherthala S Rural 10 18 0 0 Hotel Janakeeya 16 Alappuzha Chingoli souhridam unit karthikappally l p school Rural 3 163 0 0 Hotel Janakeeya 17 Alappuzha Chunakkara Vanitha Canteen Chunakkara Rural 3 0 0 0 Hotel Janakeeya 18 Alappuzha Ezhupunna Neethipeedam Eramalloor Rural 8 0 0 4 Hotel Janakeeya 19 Alappuzha Harippad Swad A private Hotel's Kitchen Urban 4 0 0 0 Hotel Janakeeya 20 Alappuzha Kainakary Sivakashi Near Panchayath Rural 5 0 0 0 Hotel 43 LUNCH LUNCH LUNCH Home No. -

Trends in Indian Historiography

HIS2B02 - TRENDS IN INDIAN HISTORIOGRAPHY SEMESTER II Core Course BA HISTORY CBCSSUG (2019) (2019 Admissions Onwards) School of Distance Education University of Calicut HIS2 B02 Trends in Indian Hstoriography University of Calicut School of Distance Education Study Material B.A.HISTORY II SEMESTER CBCSSUG (2019 Admissions Onwards) HIS2B02 TRENDS IN INDIAN HISTORIOGRAPHY Prepared by: Module I & II :Dr. Ancy. M. A Assistant Professor School of Distance Education University of Calicut. Module III & IV : Vivek. A. B Assistant Professor School of Distance Education University of Calicut. Scrutinized by : Dr.V V Haridas, Associate Professor, Dept. of History, University of Calicut. MODULE I Historical Consciousness in Pre-British India Jain and Bhuddhist tradition Condition of Hindu Society before Buddha Buddhism is centered upon the life and teachings of Gautama Buddha, where as Jainism is centered on the life and teachings of Mahavira. Both Buddhism and Jainism believe in the concept of karma as a binding force responsible for the suffering of beings upon earth. One of the common features of Bhuddhism and jainism is the organisation of monastic orders or communities of Monks. Buddhism is a polytheistic religion. Its main goal is to gain enlightenment. Jainism is also polytheistic religion and its goals are based on non-violence and liberation the soul. The Vedic idea of the divine power of speech was developed into the philosophical concept of hymn as the human expression of the etheric vibrations which permeate space and which were first knowable cause of creation itself. Jainism and Buddhism which were instrumental in bringing about lot of changes in the social life and culture of India. -

Travancore-Cochin Integration; a Model to Native States of India

Journal of Xi'an University of Architecture & Technology ISSN No : 1006-7930 Travancore-Cochin Integration; A model to Native states of India Dr Suresh J Assistant Professor, Department Of History University College, Thiruvanathapuram Kerala University Abstract The state of Kerala once remained as an integral part of erstwhile Tamizakaom. Towards the beginning of the modern age this political terrain gradually enrolled as three native kingdoms with clear cut boundaries. The three native states comprised kingdom of Travancore of kingdom of Cochin, kingdom of Calicut These territories never enjoyed a single political structure due to the internal and foreign interventions. Travancore and Cochin were neighboring states enjoyed cordial relations. The integration of both states is a unique event in the history of India as well as History of Kerala. The title of Rajapramukh and the administrative division of Dewaswam is unique aspect in the course of History. Keywords Rajapramukh , Dewaswam , Panjangam, Yogam, annas, oorala, Melkoima Introduction The erstwhile native state of Travancore and Cochin forms political unity of Indian sub- continent through discussions debates and various agreements. The states situating nearby maintained interstate reactions in various realms. At occasionally they maintained cordial relation on the other half hostile in every respect. In different epochs the diplomatic relations of both the state were unique interns of political economic, social and cultural aspects. This uniqueness ultimately enabled both the state to integrate them ultimate into the concept of the formation of the state of Kerala. The division of power in devaswams and assumed the title Rajapramukh is unique chapters in Kerala as well as Indian history Volume XII, Issue VII, 2020 Page No: 128 Journal of Xi'an University of Architecture & Technology ISSN No : 1006-7930 Scope and relevance of Study Travancore and Cochin the native states of southern kerala. -

List of Lacs with Local Body Segments (PDF

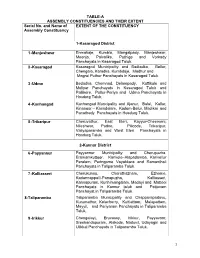

TABLE-A ASSEMBLY CONSTITUENCIES AND THEIR EXTENT Serial No. and Name of EXTENT OF THE CONSTITUENCY Assembly Constituency 1-Kasaragod District 1 -Manjeshwar Enmakaje, Kumbla, Mangalpady, Manjeshwar, Meenja, Paivalike, Puthige and Vorkady Panchayats in Kasaragod Taluk. 2 -Kasaragod Kasaragod Municipality and Badiadka, Bellur, Chengala, Karadka, Kumbdaje, Madhur and Mogral Puthur Panchayats in Kasaragod Taluk. 3 -Udma Bedadka, Chemnad, Delampady, Kuttikole and Muliyar Panchayats in Kasaragod Taluk and Pallikere, Pullur-Periya and Udma Panchayats in Hosdurg Taluk. 4 -Kanhangad Kanhangad Muncipality and Ajanur, Balal, Kallar, Kinanoor – Karindalam, Kodom-Belur, Madikai and Panathady Panchayats in Hosdurg Taluk. 5 -Trikaripur Cheruvathur, East Eleri, Kayyur-Cheemeni, Nileshwar, Padne, Pilicode, Trikaripur, Valiyaparamba and West Eleri Panchayats in Hosdurg Taluk. 2-Kannur District 6 -Payyannur Payyannur Municipality and Cherupuzha, Eramamkuttoor, Kankole–Alapadamba, Karivellur Peralam, Peringome Vayakkara and Ramanthali Panchayats in Taliparamba Taluk. 7 -Kalliasseri Cherukunnu, Cheruthazham, Ezhome, Kadannappalli-Panapuzha, Kalliasseri, Kannapuram, Kunhimangalam, Madayi and Mattool Panchayats in Kannur taluk and Pattuvam Panchayat in Taliparamba Taluk. 8-Taliparamba Taliparamba Municipality and Chapparapadavu, Kurumathur, Kolacherry, Kuttiattoor, Malapattam, Mayyil, and Pariyaram Panchayats in Taliparamba Taluk. 9 -Irikkur Chengalayi, Eruvassy, Irikkur, Payyavoor, Sreekandapuram, Alakode, Naduvil, Udayagiri and Ulikkal Panchayats in Taliparamba -

The Chirakkal Dynasty: Readings Through History

THE CHIRAKKAL DYNASTY: READINGS THROUGH HISTORY Kolathunadu is regarded as one of the old political dynasties in India and was ruled by the Kolathiris. The Mushaka vamsam and the kings were regarded as the ancestors of the Kolathiris. It was mentioned in the Mooshika Vamsa (1980) that the boundary of Mooshaka kingdom was from the North of Mangalapuram – Puthupattanam to the Southern boundary of Korappuzha in Kerala. In the long Sanskrit historical poem Mooshaka Vamsam, the dynastic name of the chieftains of north Malabar (Puzhinad) used is Mooshaka (Aiyappan, 1982). In the beginning of the fifth Century A.D., the kingdom of Ezhimala had risen to political prominence in north Kerala under Nannan… With the death of Nannan ended the most glorious period in the history of the Ezhimala Kingdom… a separate line of rulers known as the Mooshaka kings held sway over this area 36 (Kolathunad) with their capital near Mount Eli. It is not clear whether this line of rulers who are celebrated in the Mooshaka vamsa were subordinate to the Chera rulers of Mahodayapuram or whether they ruled as an independent line of kings on their own right (in Menon, 1972). The narration of the Mooshaka Kingdom up to the 12th Century A.D. is mentioned in the Mooshaka vamsa. This is a kavya (poem) composed by Atula, who was the court poet of the King Srikantha of Mooshaka vamsa. By the 14th Century the old Mooshaka kingdom had come to be known as Kolathunad and a new line of rulers known as the Kolathiris (the ‘Colastri’ of European writers) had come into prominence in north Kerala. -

History of Onattukara WAFFEN-UND KOSTUMKUNDE JOURNAL Volume XI, Issue XI, November/2020 ISSN NO: 0042-9945 Page No: 89

WAFFEN-UND KOSTUMKUNDE JOURNAL ISSN NO: 0042-9945 History of Onattukara Dr. R. Rajesh, Associate Professor N.S.S College, Pandalam. Kerala, India Odanad was a small kingdom during the second Chera Empire between (800-1102). Mahodyapuram acted as the capital for the kingdom which lasted more than three centuries. The historical Odanad comprised parts of modern-day Kerala which includes Mavelikkara and Karthikapalli from the Alappuzha district and Karunagapalli from Kollam district. Later in history, it became known as Kayamkulam Kingdom. Onattukara is synonymous with Odanad. The geographical boundaries of Odanad were the south of Kannett, the northern parts of Trikunnapuzha, in the west, it was the Arabian sea and in the east, it was bordered by Ilayidath Swaroopam. In the 14th century text, Unnuneeli Sandesam Kannett is mentioned as the southern border of the kingdom. According to the records by The Dutch Commander of Cochin, Julius Valentyn Stein van Gollenesse in 1734 AD, the neighbourhood of Odanad were the areas of Pandalam, Thekkumkur, Ilayidath Swaroopam, Maadathukur, Purakkad and Thrikkunnapuzha. Madathumkur and Kannett which were the southern parts of the kingdom later separated from Odanad. During the time of Perumakkan Kings of Mahodayapuram. The whole countryside was divided into small states which had its right of self-government like Venad, Odanad, Nandruzainad, Eranadu,Munjunad, Vembamalnad, Valluvanad, Eralnad, Puraikizhanadu etc. Several written proofs show that until the end of the 12th century Perumakan's Mahodhyapuram acted as the capital to the kingdom that stretched between Thiruvananthapuram and Kolathunadu. Popular historian Elamkulam Kunjan Pillai argues that even though the records aren't crystal clear, It has to be believed that this geographical division of kingdom existed at the beginning of the 12th century and places like Odanad and Venad attained freedom only during this time. -

HIDDEN DELIGHTS There Are the Sea and Backwaters, of Course, but This Charming Town in Kerala Has Several Other Attractions, Discovers Ankita S

GO TRAVEL ALLEPPEY ALLEPPEY’S HIDDEN DELIGHTS There are the sea and backwaters, of course, but this charming town in Kerala has several other attractions, discovers Ankita S lleppey’s mainstay used to be the coir and paddy industries. After all, Kuttanad, known as the ‘rice bowl of India’, is located in Alappuzha, as it is also known. Today, tourism and the houseboat business keep the city’s A economy buoyant. But as Saju Thomas, the General Manager of Ramada Alleppey told us, the government is smart enough to have the houseboats dock elsewhere to preserve the beauty of one of Kerala’s best known coastal towns. We embarked on a day-long tour of Alleppey city, a departure from the usual houseboat cruise routine. Our driver took us to the Revi Karuna Karan Memorial Museum of his own accord — a private art collection that was probably worth a visit but we were keener on seeing the International Coir Museum. The array of paintings, creatures and objects creatively fashioned from coir convinced us that we made the right choice. Most striking among the artefacts were a tall Ganesha, a 3D installation of a rural scene in Kerala and a replica of the Baha’i Lotus Temple in Delhi made of coir. The museum also walked us through the fascinating history of Kerala’s coir industry. Go Alleppey FIN.indd 86-87 11/27/17 9:41 PM GO TRAVEL ALLEPPEY ALLEPPEY’S HIDDEN DELIGHTS There are the sea and backwaters, of course, but this charming town in Kerala has several other attractions, discovers Ankita S lleppey’s mainstay used to be the coir and paddy industries. -

Jews: an Historical Exploration Through the Shores of Kerala History

IOSR Journal Of Humanities And Social Science (IOSR-JHSS) Volume 20, Issue 9, Ver. VI (Sep. 2015) PP 43-45 e-ISSN: 2279-0837, p-ISSN: 2279-0845. www.iosrjournals.org Jews: an Historical Exploration through the shores of Kerala History Dr. Sumi Mary Thomas Assistant Professor, Dept. of History, CMS College, Kottayam, Kerala, 686001 Kerala, also known as Gods own Country, is a state in the South West region of India. The state was formed on November 1956 by combining various Malayalam speaking regions. From the early days Kerala is famous for trade, particularly for spices which attracted traders from different parts of the world. As per Sumerian records Kerala is referred as the ‘Garden of spices’ or ‘The spice garden of India’. The state has attracted Babylonians, Assyrians, Egyptians, Arabs, Greeks and Romans. Merchants from West Asia and Southern Europe established coastal ports and settlements in Kerala. Jewish connection with Kerala was started in the tenth Century B C. The Jews are an ethnic group who settled first in Muziris, the earliest seaport in Kerala which was known as ‘Little Jerusalem’. They came to Kerala during the period of King Solomon. It is believed that King Solomon had visited Kerala for trade purposes. From the very early days the country Kerala was known to the ancient Jews. In the 6th century BC the Jews came to Kodungaloor in order to escape from the Babylonian captivity of Nebuchednezzar. In 580 B C the Babylonian Empire conquered Yehudah (Judah), the Southern region of ancient Israel. After 50 years later, the Persian Empire (ancient Iran) conquered the Babylonian Empire and allowed the Jews to return home to the land of Israel. -

1. Introduction

1. INTRODUCTION 1.1. History Kasaragod, the northernmost district of Kerala, is endowed with rich natural resources and is noted for its majestic forts, ravishing rivers, hills, green valleys and beautiful beaches. The rich and varied cultural heritage of the district is portrayed through spectacular presentations of Theyyam, Yakshagana, Poorakkali, Kolkali and Mappilappattu. Seven languages are prevalent in Kasaragod. Malayalam is the administrative language. Other languages are Kannada, Tulu, Konkani, Marati, Urdu and Beary.Prior to State reorganization, Kasaragod was part of the South Kanara district.Kasaragod became a part of Malabar district following the reorganization of States and formation of unified Kerala State. Later, Kasaragod Taluk of Malabar district was bifurcated in to Kasaragod and Hosdurg Taluks and integrated with the then newly formed Cannanore district. Kasaragod became part of Kerala following the re-organization of states and formation of Kerala in 1st November 1956.The district was Kasaragod Taluk in Kannur District.The formation of Kasaragod district was a long felt ambition of the people.It is with the intention of bestowing maximum attention on the development of backward area, Kasaragod district was formed on 24th May,1984 as per GO (MS)No.520/84/RD, Dated 19.05.1984 by taking Kasaragod and Hosdurg taluks from the then Kannur district.The name Kasaragod is said to be derived from the word Kasaragod which means Nuxvemied Forest(Kanjirakuttam). 1.2. Physiography Kasaragod is bounded on the north and the east by Dakshina Kannada and Coorg districts of Karnataka State, on the south by Kannur district and on the west by the Lakshadweep Sea. -

Kollam Port : an Emporium of Chinese Trade

ADVANCE RESEARCH JOURNAL OF SOCIAL SCIENCE A REVIEW Volume 9 | Issue 2 | December, 2018 | 254-257 ISSN–0976–56111 DOI: 10.15740/HAS/ARJSS/9.2/254-257 Kollam Port : An emporium of Chinese trade H. Adabiya Department of History, Iqbal College, Peringammala, Thiruvananthapuram (Kerala) India Email: adabiyaiqbal@gmail. com ARTICLE INFO : ABSTRACT Received : 21.10.2018 Kerala had maintained active trade relations across the sea with many countries of the Accepted : 26.11.2018 Eastern and Western world. Kollam or Quilon was a major trading centre on the coast of Kerala from the remote past and has a long drawing attraction worldwide. The present paper seeks to analyze the role and importance of Kollam port in the trade KEY WORDS : relation with China. It is an old sea port town on the Arabian coast had a sustained Maritime relations, Emporium, commercial reputation from the days of Phoenicians and the Romans. It is believed Chinese trade, Commercial hub that Chinese were the first foreign power who maintains direct trade relation with Kollam. It was the first port where the Chinese ships could come through the Eastern Sea. Kollam had benefitted largely from the Chinese trade, the chief articles of export from Kollam were Brazil wood or sapang, spices, coconut and areca nut. All these HOW TO CITE THIS ARTICLE : goods had great demand in China and the Chinese brought to Kerala coast goods like Adabiya, H. (2018). Kollam port : An emporium of Chinese trade. Adv. Res. J. silk, porcelain, copper, quick silver, tin, lead etc. Chinese net and ceramics of China Soc. -

Ahtl-European STRUGGLE by the MAPPILAS of MALABAR 1498-1921 AD

AHTl-EUROPEAn STRUGGLE BY THE MAPPILAS OF MALABAR 1498-1921 AD THESIS SUBMITTED FDR THE AWARD OF THE DEGREE DF Sactnr of pitilnsopliQ IN HISTORY BY Supervisor Co-supervisor PROF. TARIQ AHMAD DR. KUNHALI V. Centre of Advanced Study Professor Department of History Department of History Aligarh Muslim University University of Calicut Al.garh (INDIA) Kerala (INDIA) T6479 VEVICATEV TO MY FAMILY CONTENTS SUPERVISORS' CERTIFICATE ACKNOWLEDGEMENT LIST OF MAPS LIST OF APPENDICES ABBREVIATIONS Page No. INTRODUCTION 1-9 CHAPTER I ADVENT OF ISLAM IN KERALA 10-37 CHAPTER II ARAB TRADE BEFORE THE COMING OF THE PORTUGUESE 38-59 CHAPTER III ARRIVAL OF THE PORTUGUESE AND ITS IMPACT ON THE SOCIETY 60-103 CHAPTER IV THE STRUGGLE OF THE MAPPILAS AGAINST THE BRITISH RULE IN 19™ CENTURY 104-177 CHAPTER V THE KHILAFAT MOVEMENT 178-222 CONCLUSION 223-228 GLOSSARY 229-231 MAPS 232-238 BIBLIOGRAPHY 239-265 APPENDICES 266-304 CENTRE OF ADVANCED STUDY DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY ALIGARH MUSLIM UNIVERSITY ALIGARH - 202 002, INDIA CERTIFICATE This is to certify that the thesis "And - European Struggle by the Mappilas of Malabar 1498-1921 A.D." submitted for the award of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of the Aligarh Muslim University, is a record of bonafide research carried out by Salahudheen O.P. under our supervision. No part of the thesis has been submitted for award of any degree before. Supervisor Co-Supervisor Prof. Tariq Ahmad Dr. Kunhali.V. Centre of Advanced Study Prof. Department of History Department of History University of Calicut A.M.U. Aligarh Kerala ACKNOWLEDGEMENT My earnest gratitude is due to many scholars teachers and friends for assisting me in this work. -

History-. of ··:Kerala: - • - ' - - ..>

HISTORY-. OF ··:KERALA: - • - ' - - ..> - K~ P. PAD!rlANABHA .MENON.. Rs. 8. 18 sh. ~~~~~~ .f-?2> ~ f! P~~-'1 IY~on-: f. L~J-... IYt;;_._dh, 4>.,1.9 .£,). c~c~;r.~, ~'").-)t...q_ A..Ja:..:..-. THE L ATE lVIn. K. P . PADJVIANABHA MENON. F rontispiece.] HISTORY· op::KERALA. .. :. ' ~ ' . Oowright and right of t'fanslation:. resen;e~ witk ' Mrs. K. P. PADMANABHA MENON. Copies can be had of . '. Mrs. K. P. PAI>MANABHA MENON, Sri Padmanabhalayam Bungalow~, Diwans' Road;-!Jmakulam, eochin state, S.INDIA. HISTORY OF KERALA. A HISTORY OF KERALA. WBI'l!TEN, IN THE FOBH OF NOTES ON VISSCHER'S LETTERS FROM MALABAR, BY K. P. PADMANABHA MENON, B.A., S.L, M.~.A.S., ' . Author of the History of Codzin, anti of severai P~p~rsconnectedwith the early History of Kerala; Jiak•l of the H1g-k Courts of Madras 0,.. of Travam:ore and of tke Ckief Court of. Cochin, ~ . • r . AND .EDITED BY SAHITHYAKUSALAN. "T. :K.' KRISHNA MENON, B. A.;~. • ' "'•.t . fl' Formerly, a Member of Jhe Royal Asiatic Society, and of the ~ocieties of Arts and of Aut/tors, 'anti a Fellow of the .Royal Histor~cal .Soci'ety. Kun.kamhu NamfJiyar Pr~sd:ian. For some ti'me, anE:cami'n.er for .Malayalam to the Umverfities of Madras, Benares and Hydera bad. A Member (Jf the .Board of Stzediet for Malayalam. A fJUOndum Editor of Pid,.a Vinodini. A co-Editor of tke ., .Sciene~ Primers Seriu in Malayalam. Editor of .Books for Malabar Bairns: The Author &- Editor of several works in Malayalam. A Member of the, Indian Women's Uni'r,ersity, and · · a .Sadasya of Visvn-.Bharatki, &-c.