Aesthetical Attributes for Segmenting Arabic Word

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Applying Arabic Kashida to Latin Letters in Display Typography

Applying Arabic Kashida to Latin Letters in Display Typography Antoine Abi Aad Ph.D., Lecturer - Coordinator, Advertising and Graphic Design, Académie Libanaise des Beaux- Arts, UOB, Lebanon [email protected] Abstract-Arabic, like Hebrew, is a script that was Syriac scripts were developed from Aramaic. Figure extensively used visually because of religious 2 represents one sentence written in Syriac and in 5 purposes. In Islam, as in Judaism, the visual Arabic . The similarities between the two scripts are representation of saints, prophets and holy people is evident. not allowed. However, the desire and the passion to create images were stronger than the fear of blasphemy. Figure 1 has three word-pictures: the first is a Masoretic illustrated text written in Hebrew1 and the other two are animals drawn with Arabic letters: the bird is written in Turkish2 while the tiger is Figure 2. Syriac and Arabic letters written in Persian3. The Kashida replaces the letter space used with Latin letters. Furthermore, it improves the appearance of justified text by visually lengthening words rather than increasing the blank between the letters. Interestingly, the Kashida can be stretched unevenly in one word, serving aesthetics needs. Figure 1. Words as image Today, people using Arabic letters are linked to many centuries of visual words, a heritage that can be transformed into display typography. It is pointless to keep reminiscing on the splendors of great eras. Artists and designers should rather look inward yet forward and produce new visuals. This paper explores display typography through the kashida, the soul of Arabic writing. Applied to Latin letters, the Figure 3. -

The Transformation of Calligraphy from Spirituality to Materialism in Contemporary Saudi Arabian Mosques

The Transformation of Calligraphy from Spirituality to Materialism in Contemporary Saudi Arabian Mosques A dissertation submitted to Birmingham City University in fulfilment of the requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Art and Design By: Ahmad Saleh A. Almontasheri Director of the study: Professor Mohsen Aboutorabi 2017 1 Dedication My great mother, your constant wishes and prayers were accepted. Sadly, you will not hear of this success. Happily, you are always in the scene; in the depth of my heart. May Allah have mercy on your soul. Your faithful son: Ahmad 2 Acknowledgments I especially would like to express my appreciation of my supervisors, the director of this study, Professor Mohsen Aboutorabi, and the second supervisor Dr. Mohsen Keiany. As mentors, you have been invaluable to me. I would like to extend my gratitude to you all for encouraging me to conduct this research and give your valuable time, recommendations and support. The advice you have given me, both in my research and personal life, has been priceless. I am also thankful to the external and internal examiners for their acceptance and for their feedback, which made my defence a truly enjoyable moment, and also for their comments and suggestions. Prayers and wishes would go to the soul of my great mother, Fatimah Almontasheri, and my brother, Abdul Rahman, who were the first supporters from the outset of my study. May Allah have mercy on them. I would like to extend my thanks to my teachers Saad Saleh Almontasheri and Sulaiman Yahya Alhifdhi who supported me financially and emotionally during the research. -

Developing an Arabic Typography Course for Visual Communication Design

Developing an Arabic Typography course for Visual Communication Design Students in the Middle East and North African Region A thesis submitted to the School of Visual Communication Design, College of Communication and Information of Kent State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Fine Arts by Basma Almusallam May, 2014 Thesis written by Basma Almusallam B.F.A, Kuwait University, 2008 M.F.A, Kent State University, 2014 Approved by ___________________________ Jillian Coorey, M.F.A., Advisor ___________________________ AnnMarie LeBlanc, M.F.A., Director, School of Visual Communication Design ___________________________ Stanley T. Wearden, Ph.D., Dean, College of Communication and Information Table of Contents TABLE OF CONTENTS………………………………………………………………...... iii LIST OF FIGURES……………………………………………………………………….. v PREFACE………………………………………………………………………………..... vi CHAPTER I. INTRODUCTION…………………………………………………………. 1 The Current Issue………………………………………………….. 1 Core Objectives……………………………………………………. 3 II. THE HISTORY OF THE ARABIC WRITING SYSTEM, CALLIGRAPHY AND TYPOGRAPHY………………………………………....………….. 4 The Arabic Writing System……………………………………….. 4 Arabic Calligraphy………………………………………………… 5 The Undocumented Art of Arabic Calligraphy……………….…… 6 The Shift Towards Typography and the Digital Era………………. 7 The Pressing Issue of the Present………………………………….. 8 A NOTE ON THE PROCESS…………………………………………………………….. 10 Applying a Framework for Research Documentation…………….. 11 Mental Model……………………………………………………… 12 Proposed User Testing……………………………………………. -

Richard Ishida 2

Richard Ishida 2 The Internaonalizaon Working Group at the W3C is involved in reviewing specificaons for internaonalizaon issues – specificaons from inside and outside W3C. It also creates resources for content authors, specificaon developers and others related to internaonalizaon features of the Open Web Plaorm, including educaonal ar0cles, tests, etc. This presentaon will focus on one addi0onal area that has been gathering pace recently – the development of documents that describe text layout requirements for a given language or script. We will start by giving a brief outline of a couple of issues that illustrate the need for these documents. 3 The CSS3 Text module (hNp://www.w3.org/TR/css3-text/) will specify how to apply internaonal typographic effects to web pages. One example is text jus0ficaon, which produces straight lines down both the leU and right margins. Richard Ishida 4 Let's suppose that we want to jus0fy this Arabic text, so that there are straight lines at both leU and right margins. Generally speaking, received wisdom says that Arabic does this by stretching the baseline inside words, rather than stretching the inter-word spacing (as would be the case in English text). Richard Ishida 5 To make it simple, lets just focus on these two lines. Richard Ishida 6 One way you may hear that this can be done is by using a special baseline extension character in Unicode, U+0640 ARABIC TATWEEL. The slide shows some Arabic text from a newspaper where we have jus0fied the first two lines using tatweels in exactly the same way it was done in the newspaper. -

New Features in Mpdf V6.0

NewNew FeaturesFeatures inin mPDFmPDF v6.0v6.0 Advanced Typography Many TrueType fonts contain OpenType Layout (OTL) tables. These Advanced Typographic tables contain additional information that extend the capabilities of the fonts to support high-quality international typography: ● OTL fonts support ligatures, positional forms, alternates, and other substitutions. ● OTL fonts include information to support features for two-dimensional positioning and glyph attachment. ● OTL fonts contain explicit script and language information, so a text-processing application can adjust its behavior accordingly. mPDF 6 introduces the power and flexibility of the OpenType Layout font model into PDF. mPDF 6 supports GSUB, GPOS and GDEF tables for now. mPDF 6 does not support BASE and JSTF at present. Other mPDF 6 features to enhance complex scripts: ● improved Bidirectional (Bidi) algorithm for right-to-left (RTL) text ● support for Kashida for justification of arabic scripts ● partial support for CSS3 optional font features e.g. font-feature-settings, font-variant ● improved "autofont" capability to select fonts automatically for any script ● support for CSS :lang selector ● dictionary-based line-breaking for Lao, Thai and Khmer (U+200B is also supported) ● separate algorithm for Tibetan line-breaking Note: There are other smart-font technologies around to deal with complex scripts, namely Graphite fonts (SIL International) and Apple Advanced Typography (AAT by Apple/Mac). mPDF 6 does not support these. What can OTL Fonts do? Support for OTL fonts allows the faithful display of almost all complex scripts: (ܐSyriac ( ,(שלום) Hebrew ,(اﻟﺴﻼم ﻋﻠﻴﻢ) Arabic ● ● Indic - Bengali (ামািলকুম), Devanagari (नमते), Gujarati (નમતે), Punjabi (ਸਿਤ ਸੀ ਅਕਾਲ), Kannada ( ), Malayalam (നമെ), Oriya (ନମସ୍କର), Tamil (வணக்கம்), Telugu ( ) ನಮ ជបសួរំ నమరం ● Sinhala (ආයුෙඛා්වන්), Thai (สวัสดี), Lao (ສະບາຍດີ), Khmer ( ), Myanmar (မဂလပၝ), Tibetan (བ་ས་བ་གས།) Joining and Reordering র + ◌্ + খ + ◌্ + ম + ◌্ + ক + ◌্ + ষ + ◌্ + র + ি◌ + ◌ু = িু cf. -

Language Culture Type 2.Indd

Arabic script and typography is alphabetical; the direction of writing is from right to left; within a word, most letters form connected groups. AOne expects an alphabet to consist of a few dozen letters repre- senting one unique sound each. The Arabic alphabet evolved somewhat away from this ideal: although most letters correspond to a sound, a few letters are ambivalent between two or more sounds. Some letters don’t represent sound at all: they have only a grammatical function. For modern office use there are 28 basic letters, eight of them only differentiated from other letters by diacritics, and six optional letters for representing vowels. Older spellings made less use of diacritics for dif- ferentiating; on the other hand, to facilitate Qur’an recitation, additional vowel signs occur, along with elaborate cantillation marks. To acknowl- edge slight variations of the received text, some Qur’an editions have ad- ditional diacritics, discretely adding or eliminating consonant letters. As the Arabic script evolved into a connected script, it developed an elaborate system of assimilations and dissimilations between adjacent letters. Outside a small group of connoisseurs and calligraphers who study the principles established by the Ottoman letter artists, surpris- ingly little is understood of the efficiency and subtlety of this system,¹ and modern industrial type designs follow the approach found in el- ementary Western teaching materials.² There, beginners in Arabic script are given a maximally simplified scheme. While simplification is totally sound from a pedagogical perspective, it provides too narrow a basis for the development of professional typography. The Arabic script stems from the same source as the Latin, Greek, and Hebrew writing systems: Phoenician (figure 1).³ The underlying proto- alphabet had some two dozen characters; there were no vowels. -

Designing Software to Meet the Needs of International Users

DESIGNING SOFTWARE TO MEET THE NEEDS OF INTERNATIONAL USERS A Project Report Presented to The Faculty of the Department of Anthropology San José State University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts by David Mohr December 2013 © 2013 David Mohr ALL RIGHTS RESERVED SAN JOSÉ STATE UNIVERSITY The Undersigned Graduate Committee Approves the Project Report Titled DESIGNING SOFTWARE TO MEET THE NEEDS OF INTERNATIONAL USERS by David Mohr APPROVED FOR THE DEPARTMENT OF ANTHROPOLOGY _____________________________________________________________________________ Dr. Chuck Darrah, Department of Anthropology Date _____________________________________________________________________________ Dr. Roberto Gonzalez, Department of Anthropology Date _____________________________________________________________________________ Professor Awad Awad, Middle Eastern Studies, Department of Humanities, Date Arabic Coordinator, Department of World Languages and Literatures Abstract Most software applications are designed and built in North America, catering to English- speaking, North American users. Ethnography is commonly used to ensure the product addresses the needs of domestic customers, but there is no analogous research with regard to foreign consumers. As a result, often times the features in these applications fail to sufficiently address the needs, expectations, and workflow of non-English-speaking users. Although software engineering manuals minutely detail the technical aspects of bringing an English application to -

Digital Quran Computing: Review, Classification, and Trend Analysis

Arab J Sci Eng DOI 10.1007/s13369-017-2415-4 REVIEW ARTICLE - COMPUTER ENGINEERING AND COMPUTER SCIENCE Digital Quran Computing: Review, Classification, and Trend Analysis Mohammed Zakariah1 · Muhammad Khurram Khan2 · Omar Tayan3,4 · Khaled Salah5 Received: 18 July 2016 / Accepted: 9 January 2017 © King Fahd University of Petroleum & Minerals 2017 Abstract The proliferation of online digital multimedia categorization based on the topical trends from recent con- content has enabled the rapid digitization of printed ferences and symposia related to DQC. Second, a review is manuscripts, resulting in faster and more effective dissem- given for papers under each theme with a discussion of their ination of digital publications. This scenario is also found key features, limitations, and research directions. Finally, a in the context of digital Quran content, which has recently number of research hot spots that identify open challenges gained significant traction from the research and scientific and primary areas in DQC for future work are outlined. communities with related discussions and studies covering a range of IT subject domains under the generic topic of Digital Keywords Holy Quran · Digital Quran Computing · Quran Computing (DQC). In the past few years, a number of Multimedia · Arabic digitization · Mobile applications · international conferences and symposia have been dedicated WorldWideWeb to the concept of DQC. This paper surveys and reports on the developmental trends and research hotspots in DQC, provid- ing up-to-date theme categories and an analysis of published 1 Introduction articles in the literature. First, the study provides a theme The Holy Quran is the book of divine guidance and direc- B Khaled Salah tion for humanity. -

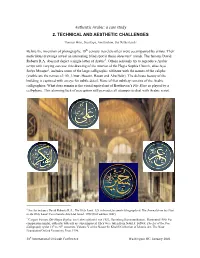

Authentic Arabic: a Case Study 2. TECHNICAL and AESTHETIC CHALLENGES

Authentic Arabic: a case study 2. TECHNICAL AND AESTHETIC CHALLENGES Thomas Milo, DecoType, Amsterdam, the Netherlands Before the invention of photography, 19th century travelers often were accompanied by artists. Their meticulous drawings reveal an interesting blind spot in these observers’ minds. The famous David Roberts R.A. does not depict a single letter of Arabic1. Others seriously try to reproduce Arabic script with varying success: this drawing of the interior of the Hagia Sophia Church, alias Aya Sofya Mosque2, includes some of the large calligraphic tableaux with the names of the caliphs (visible are the names of: Ali, Umar, Husain, Hasan and Abu Bakr). The delicate beauty of the building is captured with an eye for subtle detail. None of that subtlety remains of the Arabic calligraphies. What does remain is the visual equivalent of Beethoven’s Für Elise as played by a cell-phone. This alarming lack of perception still pervades all attempts to deal with Arabic script. 1 See for instance David Roberts R.A., The Holy Land, 123 coloured facsimile lithographs & The Journal from his Visit to the Holy Land, Terra Sancta Arts Ltd, Israel, 1982 (first edition 1842) 2 Caspare Fossati, Die Hagia Sophia, nach dem tafelwerk von 1852, Harenberg Kommunikation , Dortmund 1980. For comparison similar, authentic tableaux are superimposed. They were taken from Nabil F. Safwat, The Art of the Pen, Calligraphy of the 14th to 20th centuries, Volume V of the Nasser D. Khalili Collection of Islamic Art, The Nour Foundation/Oxford University Press 1996. 20th International Unicode Conference Washington DC, January 2002 Authentic Arabic 2 – Technical and Æsthetic Challenges A more recent illustration is a drawing of the interior of the Süleymaniye Mosque in Istanbul3. -

Arabic Typesetting Using a METAFONT-Based Dynamic Font

Arabic typesetting using a METAFONT-based dynamic font Amine Anane [email protected] TUG 2019 - Palo Alto, California, USA August 9-11, 2019 How the project started ? I cannot find a searchable pdf document of the Quran. PDF documents are raster images of hand-written book : cannot be searchable. big size. blurry image due to pixelation Other formats (Office Word, HTML [http://tanzil.net]) : based on Unicode text file + OpenType Font. 1 OpenType Font vs Handwritten text Much smaller font size to accommodate the widest line Increase in interword space for other lines 2 Objective Typeset an electronic copy of the Medina Mus’haf (book) re- specting calligraphic rules and having the same Font size, page number and line Why Medina book ? Quranic book is a reference in Arabic calligraphy Written by one of the most renowned Arabic calligrapher beautiful, clear, easy-to-read style each page finishes by a verse and each section (30 sections) in 20pages (15 lines each) Justification is applied extensively If objective is reached, we should reach ultimate goal : High-quality Arabic → typesetter fulfilling Arabic calligraphic rules 3 Where to start? Existing systems and technology for typesetting Arabic text Font standards such as OpenType and Apple Advanced Typography Advantage : Availability of tools Disadvantage : justification does not conform to Arabic calligraphy such as horizontal stretching using Kashida (Tatweel) ditroff/ffortid system Advantage : based on dynamic PostScript fonts Disadvantage : does not model the way stretching is done -

Classifying Arabic Fonts Based on Design Characteristics: PANOSE-A

Classifying Arabic Fonts Based on Design Characteristics: PANOSE-A Jehan Janbi A Thesis In the Department of Computer Science & Software Engineering Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Computer Science) at Concordia University Montreal, Quebec, Canada July 2016 © Jehan Janbi, 2016 Abstract In desktop publishing, fonts are essential components in each document design. With the development of font design software and tools, there are thousands of digital fonts. Increasing the number of available fonts makes selecting an appropriate font, which best serves the objective of a design, not an intuitive issue. Designers can search for a font like any other file types by using general information such as name and file format. But for document design purposes, the design features or visual characteristics of fonts are more meaningful for designers than font file information. Therefore, representing fonts’ design features by searchable and comparable data would facilitate searching and selecting a desirable font. One solution is to represent a font’s design features by a code composed of several digits. This solution has been implemented as a computerized system called PANOSE-1 for Latin script fonts. PANOSE-1 is a system for classifying and matching typefaces based on design features. It is composed of 10 digits, where each digit represents a specific design feature. It is used within several font management tools as an option for ordering and searching fonts based on their design features. It is also used in font replacement processes when an application or an operating system detects a missing font in an immigrant document or website. -

Multilingual Fonts for Arabic Script Jamil Khan* Department of Computer Science, University of Peshawar, Pakistan

chnology Te & n S o o ti ft a w a m r r Khan, J Inform Tech Softw Eng 2015, 5:3 e o f E Journal of n n I g f DOI: 10.4172/2165-7866.1000154 i o n l e a e n r r i n u g o J ISSN: 2165-7866 Information Technology & Software Engineering Research Article Open Access Multilingual Fonts for Arabic Script Jamil Khan* Department of Computer Science, University of Peshawar, Pakistan Abstract This paper is about developing a multi-lingual font for Pashto, Arabic, Urdu and Persian in such a way that the text for these four languages can be typed in it. Main purpose for developing fonts was to handle and remove many problems faced in earlier fonts. Fonts developed as a part of this work are ligature-based and text for all four languages (Pashto, Arabic, Urdu, and Persian) can be written in a single font. The paper is structured as follows: Shortcomings of existing fonts based on Arabic script and some text editors are discussed in Section-I. Section-II discusses the proposed solution to all those limitations. In Section-III, is about implementation of suggested solution, and Section-IV discusses features of the suggested solution. Section-V concludes the paper and Section-VI discusses future work discussed for Arabic typography. Keywords: Component; Formatting; Style; Styling; Insert manually in Inpage or sometimes with the help of other software such as CorelDraw. Introduction Liwal pashto system for windows During this work, some existing fonts based on Arabic script, including Pashto, Urdu, and Persian, are used in different bilingual text Liwal Pashto System–introduced in 2004 for Windows-98 and editors, and their limitations are pointed out.