Bibliographie : Autor Fabel, Ludwig Alexander

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

9789004250994.Pdf

Fragmenting Modernisms China Studies Edited by Glen Dudbridge Frank Pieke VOLUME 24 The titles published in this series are listed at brill.com/CHS Fragmenting Modernisms Chinese Wartime Literature, Art, and Film, 1937–49 By Carolyn FitzGerald LEIDEn • bOSTON 2013 Cover illustration: Ye Qianyu, “Stage Set,” from the 1940 sketch-cartoon series Wartime Chongqing. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data FitzGerald, Carolyn. Fragmenting modernisms : Chinese wartime literature, art, and film, 1937-49 / by Carolyn FitzGerald. pages cm. — (China studies ; v. 24) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-90-04-25098-7 (hardback : alk. paper) — ISBN 978-90-04-25099-4 (e-book) 1. Chinese literature—20th century—History and criticism. 2. Sino-Japanese War, 1937–1945—Literature and the war. 3. Sino-Japanese War, 1937–1945—Art and the war. 4. China—History—Civil War, 1945–1949—Literature and the war. 5. China—History— Civil War, 1945–1949—Art and the war. 6. Motion pictures—China—History—20th century. 7. Art, Chinese—20th century. 8. Modernism (Literature)—China. 9. Modernism (Art)— China. I. Title. PL2302.F58 2013 895.1’09005—dc23 2013003681 This publication has been typeset in the multilingual “Brill” typeface. With over 5,100 characters covering Latin, IPA, Greek, and Cyrillic, this typeface is especially suitable for use in the humanities. For more information, please see www.brill.com/brill-typeface. ISSN 1570-1344 ISBN 978-90-04-25098-7 (hardback) ISBN 978-90-04-25099-4 (e-book) Copyright 2013 by Koninklijke Brill NV, Leiden, The Netherlands. Koninklijke Brill NV incorporates the imprints Brill, Global Oriental, Hotei Publishing, IDC Publishers and Martinus Nijhoff Publishers. -

Contemporary China: a Book List

PRINCETON UNIVERSITY: Woodrow Wilson School, Politics Department, East Asian Studies Program CONTEMPORARY CHINA: A BOOK LIST by Lubna Malik and Lynn White Winter 2007-2008 Edition This list is available on the web at: http://www.princeton.edu/~lynn/chinabib.pdf which can be viewed and printed with an Adobe Acrobat Reader. Variation of font sizes may cause pagination to differ slightly in the web and paper editions. No list of books can be totally up-to-date. Please surf to find further items. Also consult http://www.princeton.edu/~lynn/chinawebs.doc for clicable URLs. This list of items in English has several purposes: --to help advise students' course essays, junior papers, policy workshops, and senior theses about contemporary China; --to supplement the required reading lists of courses on "Chinese Development" and "Chinese Politics," for which students may find books to review in this list; --to provide graduate students with a list that may suggest books for paper topics and may slightly help their study for exams in Chinese politics; a few of the compiler's favorite books are starred on the list, but not much should be made of this because such books may be old or the subjects may not meet present interests; --to supplement a bibliography of all Asian serials in the Princeton Libraries that was compiled long ago by Frances Chen and Maureen Donovan; many of these are now available on the web,e.g., from “J-Stor”; --to suggest to book selectors in the Princeton libraries items that are suitable for acquisition; to provide a computerized list on which researchers can search for keywords of interests; and to provide a resource that many teachers at various other universities have also used. -

T H E O F F Ic Ia L C O N Str U C Tio N O F F Em a Le Se X U a L It Y a N D G E N D E R in T H E P Eo Ple 'S R Epu B Lic O

T h e O f f ic ia l C onstruction o f F e m a l e S e x u a l it y a n d G e n d e r i n t h e P e o p l e ’ s R e p u b l ic o f C h in a 1949-1959 H arriet Evans P h D m MODERN CHINESE HISTORY UNIVERSITY OF LONDON ProQuest Number: 11015627 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 11015627 Published by ProQuest LLC(2018). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 Cfd~ ABSTRACT Issues of sexuality as expounded in the Chinese official press of the 1950s can be taken as an important indicator of the changing perception of female gender in the early People's Republic. This thesis explores the assumptions and attitudes concerning sexuality conveyed in the official media, and places particular emphasis on the projection of female attributes and responsibilities in sexual relationships. It analyses the different biological and social constructions of sexuality, and the means by which biologically determined sexual differences were inscribed with specific gender characteristics. -

Submitted for the Phd Degree at the School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London

THE CHINESE SHORT STORY IN 1979: AN INTERPRETATION BASED ON OFFICIAL AND NONOFFICIAL LITERARY JOURNALS DESMOND A. SKEEL Submitted for the PhD degree at the School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London 1995 ProQuest Number: 10731694 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 10731694 Published by ProQuest LLC(2017). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 A b s t ra c t The short story has been an important genre in 20th century Chinese literature. By its very nature the short story affords the writer the opportunity to introduce swiftly any developments in ideology, theme or style. Scholars have interpreted Chinese fiction published during 1979 as indicative of a "change" in the development of 20th century Chinese literature. This study examines a number of short stories from 1979 in order to determine the extent of that "change". The first two chapters concern the establishment of a representative database and the adoption of viable methods of interpretation. An important, although much neglected, phenomenon in the make-up of 1979 literature are the works which appeared in so-called "nonofficial" journals. -

"Ancient Mirror": an Interpretation of Gujing Ji in the Context of Medieval Chinese Cultural History Ju E Chen

East Asian History NUMBER 27 . JUNE 2004 Institute of Advanced Studies Australian National University Editor Geremie R. Barme Associate Editor Helen Lo Business Manager Marion Weeks Editorial Advisors B0rge Bakken John Clark Lo uise Edwards Mark Elvin (Convenor) John Fitzgerald Colin Jeffcott Li Tana Kam Lo uie Le wis Mayo Gavan McCormack David Marr Tessa Morris-Suzuki Benjamin Penny Kenneth Wells Design and Production Design ONE Solutions, Victoria Street, Hall ACT 2618 Printed by Goanna Print, Fyshwick, ACT This is the twenty-seventh issue of Ea st Asian History, printed August 2005, in the series previously entitled Papers on Far Ea sternHist ory. This externally refereed journal is published twice a year. Contributions to The Editor, Ea st Asian Hist ory Division of Pacific and Asian History Research School of Pacific and Asian Studies Australian National University Canberra ACT 0200, Australia Phone +61 2 6125 314 0 Fax +61 26125 5525 Email [email protected] Subscription Enquiries to Marion Weeks, East Asian History, at the above address, or to [email protected]. au Annual Subscription Australia A$50 (including GST) Overseas US$45 (GST free) (for two issues) ISSN 1036-6008 iii CONTENTS 1 Friendship in Ancient China Aat Vervoom 33 The Mystery of an "Ancient Mirror": An Interpretation of Gujing ji in the Context of Medieval Chinese Cultural History Ju e Chen 51 The Missing First Page of the Preclassical Mongolian Version of the Hs iao-ching: A Tentative Reconstruction Igor de Rachewiltz 57 Historian and Courtesan: Chen Yinke !l*Ji[Nj. and the Writing of Liu Rushi Biezhuan t9P�Qjll:J,jiJf� We n-hsin Yeh 71 Demons, Gangsters, and Secret Societies in Early Modern China Robert]. -

An Annotated Bibliography of William Faulkner, 1967-1970

Studies in English Volume 12 Article 3 1971 An Annotated Bibliography of William Faulkner, 1967-1970 James Barlow Lloyd University of Mississippi Follow this and additional works at: https://egrove.olemiss.edu/ms_studies_eng Part of the American Literature Commons Recommended Citation Lloyd, James Barlow (1971) "An Annotated Bibliography of William Faulkner, 1967-1970," Studies in English: Vol. 12 , Article 3. Available at: https://egrove.olemiss.edu/ms_studies_eng/vol12/iss1/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the English at eGrove. It has been accepted for inclusion in Studies in English by an authorized editor of eGrove. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Lloyd: Faulkner Bibliography An Annotated Bibliography of William Faulkner, 1967—1970 by James Barlow Lloyd This annotated bibliography of books and articles published about William Faulkner and his works between January, 1967, and the summer of 1970 supplements such existing secondary bibliog raphies as Maurice Beebe’s checklists in the Autumn 1956 and Spring 1967 issues of Modern Fiction Studies; Linton R. Massey’s William Faulkner: “Man Working” 1919-1962: A Catalogue of the William Faulkner Collection of the University of Virginia (Charlottesville: Bibliographic Society of the University of Virginia, 1968); and O. B. Emerson’s unpublished doctoral dissertation, “William Faulkner’s Literary Reputation in America” (Vanderbilt University, 1962). The present bibliography begins where Beebe’s latest checklist leaves off, but no precise termination date can be established since publica tion dates for periodicals vary widely, and it has seemed more useful to cover all possible material than to set an arbitrary cutoff date. -

2019 ITTF World Tour Swedish Open

2019 ITTF World Tour Swedish Open CITY: Stockholm, Sweden SITE: 1: Eriksdalshallen, Ringvägen 70 118 63 Stockholm, Sweden 2: Skanstullshallen, Bohusgatan 28 10668 Stockholm,Sweden DATE: 1-6 Octopber 2019 PLAYERS: 161 men 132 women 293 total COUNTRIES: 54 TABLES: 14 TABLE BRAND: Stiga Premium Compact BALL BRAND: DHS 40+ FLOOR BRAND: Gerflor Taraflex TT 6.2 MEDIA CONTACT: ITTF Media Officer: Elena Dubkova ([email protected]) Introduction Welcome to the 2019 ITTF World Tour Swedish Open. The Swedish Open is a Regular Series event on the ITTF World Tour, which is the latter of the two tiers (Platinum & Regular). The Swedish Open is the sixth out of six Regular Series, and the tenth event overall as the players fight for points to qualify for the season ending Seamaster 2019 ITTF World Tour Grand Final from 12- 15 December. There are five titles on offer: Men’s Singles, Women’s Singles, Men’s Doubles, Women’s Doubles & Mixed Doubles This media kit is designed to provide an update on the 2019 ITTF World Tour Swedish Open. Enclosed are statistics and notes that will be of assistance during the tournament. Players’ biographies as well as statistical, historical and personal data can be found on ITTF.com. Please make player interview requests through a member of the ITTF and OC media staff located in the press room. Key Dates/Times 01 October 2019, 09:30h @ Eriksdalshallen & Skanstullshallen – First Stage Day 1 02 October 2019, 09:30h @ Eriksdalshallen & Skanstullshallen – First Stage Day 2 03 October 2019, 10:00h @ Eriksdalshallen – Main Draw -

WTT MACAO PRESENTED by GALAXY ENTERTAINMENT GROUP MEN's SINGLES 25-29 November 2020 MACAO, CHINA

WTT MACAO PRESENTED BY GALAXY ENTERTAINMENT GROUP MEN'S SINGLES 25-29 November 2020 MACAO, CHINA BATTLE ONE BATTLE TWO ELIMINATION FINALS Random draw of non-seeded players Seeds 5-8 vs Winners of Battle One Seeds 1-4 will select their opponent from Battle Two winners DAY ONE - 25 NOVEMBER DAY TWO - 26 NOVEMBER (10) JANG Woojin (KOR) (5) LIN Yun-Ju (TPE) (1) XU Xin (CHN) PITCHFORD Liam (ENG) FANG Bo (CHN) FALCK Mattias (SWE) (9) PITCHFORD Liam (ENG) 3-1 (W4) FANG Bo (CHN) 3-2 FALCK Mattias (SWE) 3-1 WANG Chuqin (CHN) (16) FANG Bo (CHN) (6) FALCK Mattias (SWE) WANG Chuqin (CHN) 4-0 FANG Bo (CHN) FALCK Mattias (SWE) WANG Chuqin (CHN) (13) GARDOS Robert (AUT) 3-1 (W3) TSUBOI Gustavo (BRA) 3-0 (4) CALDERANO Hugo (BRA) 3-2 MA Long (CHN) (15) SALEH Ahmed (EGY) (7) WANG Chuqin (CHN) (3) LIN Gaoyuan (CHN) 5-1 WONG Chun Ting (HKG) WANG Chuqin (CHN) LIN Gaoyuan (CHN) CHAMPION (11) WONG Chun Ting (HKG) 3-2 (W2) WONG Chun Ting (HKG) 3-1 FANG Bo (CHN) 3-1 MA Long (CHN) (12) ZHAO Zihao (CHN) (8) JEOUNG Youngsik (KOR) JEOUNG Youngsik (KOR) 4-1 TSUBOI Gustavo (BRA) JEOUNG Youngsik (KOR) MA Long (CHN) (14) TSUBOI Gustavo (BRA) 3-1 (W1) PITCHFORD Liam (ENG) 3-2 (2) MA Long (CHN) 3-2 BATTLE ONE FINAL STANDING: BATTLE TWO FINAL STANDING: Quarterfinal Semifinal Final W1 PITCHFORD Liam (ENG) W1 FALCK Mattias (SWE) W2 WONG Chun Ting (HKG) W2 WANG Chuqin (CHN) W3 TSUBOI Gustavo (BRA) W3 JEOUNG Youngsik (KOR) W4 FANG Bo (CHN) W4 FANG Bo (CHN) TOP 4 SEED BATTLE PRIZE MONEY Top 4 Seeds Play each other on Day One Winners and Losers play each other on Day Two Round -

THE NATURE of VARIATION in TONE SANDHI PATTERNS of SHANGHAI and WUXI WU by Hanbo Yan Submitted to the Graduate Degree Program In

THE NATURE OF VARIATION IN TONE SANDHI PATTERNS OF SHANGHAI AND WUXI WU By © 2016 Hanbo Yan Submitted to the graduate degree program in Linguistics and the Graduate Faculty of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. ________________________________ Chairperson Dr. Jie Zhang ________________________________ Dr. Allard Jongman ________________________________ Dr. Joan Sereno ________________________________ Dr. Annie Tremblay ________________________________ Dr. Yan Li Date Defended: 05/11/2016 ii The Dissertation Committee for Hanbo Yan certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: THE NATURE OF VARIATION IN TONE SANDHI PATTERNS OF SHANGHAI AND WUXI WU ________________________________ Chairperson Dr. Jie Zhang Date approved: 05/26/2016 iii Abstract The primary goal of this dissertation is to understand the variation patterns in suprasegmental processes and what factors influence the patterns. To answer the questions, we investigated the variation patterns of tone sandhi in the Shanghai and Wuxi Wu dialects of Chinese. Shanghai disyllables and trisyllables have been documented to have two different sandhi patterns: tonal extension and tonal reduction. Some items can only undergo tonal extension, some items can only undergo tonal reduction, and some can variably undergo either type of sandhi. Previous works have indicated that the syntactic structure, semantic transparency, and lexical frequency of the items all play a role in the sandhi application. Additionally, the morpheme length of trisyllabic items (1+2, 2+1) is also expected to affect their sandhi application. A variant forms’ goodness rating experiment, together with a lexical frequency rating experiment and a semantic transparency rating experiment, showed that syntactic structure has a primary effect on sandhi application in general. -

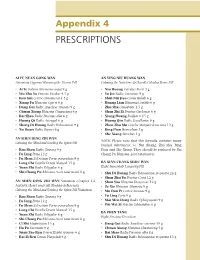

Appendix 4 PRESCRIPTIONS

Appendix 4 PRESCRIPTIONS AI FU NUAN GONG WAN AN YING NIU HUANG WAN Artemisia-Cyperus Warming the Uterus Pill Calming the Nutritive-Qi [Level] Calculus Bovis Pill • Ai Ye Folium Artemisiae argyi 9 g • Niu Huang Calculus Bovis 3 g • Wu Zhu Yu Fructus Evodiae 4.5 g • Yu Jin Radix Curcumae 9 g • Rou Gui Cortex Cinnamomi 4.5 g • Shui Niu Jiao Cornu Bubali 6 g • Xiang Fu Rhizoma Cyperi 9 g • Huang Lian Rhizoma Coptidis 6 g • Dang Gui Radix Angelicae sinensis 9 g • Zhu Sha Cinnabaris 1.5 g • Chuan Xiong Rhizoma Chuanxiong 6 g • Shan Zhi Zi Fructus Gardeniae 6 g • Bai Shao Radix Paeoniae alba 6 g • Xiong Huang Realgar 0.15 g • Huang Qi Radix Astragali 6 g • Huang Qin Radix Scutellariae 9 g • Sheng Di Huang Radix Rehmanniae 9 g • Zhen Zhu Mu Concha Margatiriferae usta 12 g • Xu Duan Radix Dipsaci 6 g • Bing Pian Borneolum 3 g • She Xiang Moschus 1 g AN SHEN DING ZHI WAN NOTE: Please note that this formula contains many Calming the Mind and Settling the Spirit Pill banned substances, i.e. Niu Huang, Zhu Sha, Bing • Ren Shen Radix Ginseng 9 g Pian and She Xiang. They should be replaced by Shi • Fu Ling Poria 12 g Chang Pu Rhizoma Acori tatarinowii. • Fu Shen Sclerotium Poriae pararadicis 9 g • Long Chi Fossilia Dentis Mastodi 15 g BA XIAN CHANG SHOU WAN • Yuan Zhi Radix Polygalae 6 g Eight Immortals Longevity Pill • Shi Chang Pu Rhizoma Acori tatarinowii 8 g • Shu Di Huang Radix Rehmanniae preparata 24 g • Shan Zhu Yu Fructus Corni 12 g AN SHEN DING ZHI WAN Variation (Chapter 14, • Shan Yao Rhizoma Dioscoreae 12 g Anxiety, Heart and Gall Bladder -

Silent Films, Hollywood Genres, and William Faulkner

SILENT FILMS, HOLLYWOOD GENRES, AND WILLIAM FAULKNER -Somdatta Mandal Much of the research concerning William Faulkner’s relationship to film focuses on the writer’s experience as a scriptwriter during the 1930s and 1940s, perhaps assuming that Faulkner’s serious interest in film began only with his arrival in Hollywood in 1932. But as Jeffrey J. Folks1 has pointed out, silent film had comprised a significant part of available popular entertainment in Oxford during Faulkner’s youth and according to Murray Falkner, Faulkner is said to have attended silent films regularly, as often as twice a week. John Faulkner says that after movies came to Oxford, which would have been about 1913, he and ‘Bill’ went every Friday - and would have gone oftener had they been allowed to.2 Though it is not possible to determine exactly what films Faulkner might have seen in the first years of film showings, the standard features certainly consisted, to a large extent of Westerns, melodramas and comedies. One may assume that among performers featured were Mary Pickford, Lilian Gish, Charles Chaplin, Buster Keaton, Harry Langdon and Fatty Arbuckle. The many Westerns that Murray Falkner recalled having seen with his brother William, may well have featured Tom Mix, William S. Hart, and Broncho Billy (G.M.Anderson) as well as many lesser known performers. Faulkner seems to have had the normal introduction to this aspect of American culture, though as an adult he may have had less contact with it. As mentioned earlier, Faulkner’s extensive knowledge of the silent film is evident from the many references to it in his fiction. -

The Liberal Arts Curriculum in China's Christian

THE LIBERAL ARTS CURRICULUM IN CHINA’S CHRISTIAN UNIVERSITIES AND ITS RELEVANCE TO CHINA’S UNIVERSITIES TODAY by Leping Mou A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Department of Leadership, Higher and Adult Education Ontario Institute for Studies in Education University of Toronto © Copyright by Leping Mou 2018 The Liberal Arts Curriculum in China’s Christian Universities and Its Relevance to China’s Universities Today Leping Mou Master of Arts Department of Leadership, Higher and Adult Education Ontario Institute for Studies in Education University of Toronto 2018 Abstract This thesis considers the historical background, the development, and the characteristics of China’s Christian universities, with a special focus on their curriculum design. Through the lens of postmodern theory, the thesis explores the concept and essence of liberal arts education as reflected in the curriculum of the Christian universities through a qualitative methodology, focusing on the analysis of historical archival material. The purpose is to find insights for today’s trend towards reviving liberal arts education in China’s elite universities as a way of countering the influence of utilitarianism and neo-liberalism in an era of economic globalization. ii Acknowledgements The completion of this Master thesis marks the accomplishment of two years’ academic study at the Ontario Institute for Studies in Education (OISE). Along with my hard work, it is made possible because of the insightful suggestions and guidance from OISE's erudite professors and the help and support from family and friends. It is also an encouragement for me to proceed to further doctoral study.