Manila's Images Are Revealing the Secrets of China's Maritime Militia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Huajin International Holdings Limited 華津國際控股有限公司 Annual Report

Huajin International Holdings Limited Huajin International Holdings Limited 華津國際控股有限公司 (Incorporated in the in Ca theyman Cayman Islands with Islands limited with liabilit limitedy) liability) Stock Code: 2738 Stock Code: 2738 華津國際控股有限公司 Annual Report Annual Report 2O17 年報 Huajin International Holdings Limited Annual Report 2017 Contents CORPORATE INFORMATION 2 DEFINITIONS 3-5 FINANCIAL HIGHLIGHTS 6 CHAIRMAN’S STATEMENT 7-8 DIRECTORS AND SENIOR MANAGEMENT 9-12 CORPORATE GOVERNANCE REPORT 13-22 MANAGEMENT DISCUSSION AND ANALYSIS 23-31 DIRECTORS’ REPORT 32-48 INDEPENDENT AUDITOR’S REPORT 49-53 CONSOLIDATED STATEMENT OF PROFIT OR LOSS AND OTHER COMPREHENSIVE INCOME 54 CONSOLIDATED STATEMENT OF FINANCIAL POSITION 55-56 CONSOLIDATED STATEMENT OF CHANGES IN EQUITY 57 CONSOLIDATED STATEMENT OF CASH FLOWS 58-59 NOTES TO THE CONSOLIDATED FINANCIAL STATEMENTS 60-101 FINANCIAL SUMMARY 102 Huajin International Holdings Limited Annual Report 2017 CORPORATE INFORMATION BOARD OF DIRECTORS PRINCIPAL SHARE REGISTRAR AND Executive Directors TRANSFER OFFICE Mr. Xu Songqing (Chairman) Conyers Trust Company (Cayman) Limited Mr. Luo Canwen (Chief Executive Officer) Cricket Square, P.O. Box 2681 Mr. Chen Chunniu Grand Cayman, KY1-1111 Mr. Xu Songman Cayman Islands Non-executive Director BRANCH SHARE REGISTRAR AND Mr. Xu Jianhong TRANSFER OFFICE Union Registrars Limited Independent non-executive Directors Suites 3301–04, 33/F., Mr. Goh Choo Hwee Two Chinachem Exchange Square, Mr. Tam Yuk Sang Sammy 338 King’s Road, North Point, Mr. Wu Chi Keung Hong Kong AUDIT COMMITTEE REGISTERED OFFICE Mr. Wu Chi Keung (Chairman) Cricket Square, Hutchins Drive Mr. Goh Choo Hwee P.O. Box 2681, Grand Cayman Mr. Tam Yuk Sang Sammy KY1-1111, Cayman Islands REMUNERATION COMMITTEE HEADQUARTER IN THE PEOPLE’S Mr. -

Printmgr File

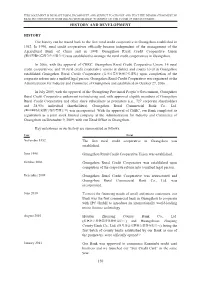

THIS DOCUMENT IS IN DRAFT FORM, INCOMPLETE AND SUBJECT TO CHANGE AND THAT THE INFORMATION MUST BE READ IN CONJUNCTION WITH THE SECTION HEADED “WARNING” ON THE COVER OF THIS DOCUMENT. HISTORY AND DEVELOPMENT HISTORY Our history can be traced back to the first rural credit cooperative in Guangzhou established in 1952. In 1996, rural credit cooperatives officially became independent of the management of the Agricultural Bank of China and in 1998, Guangzhou Rural Credit Cooperative Union ( ) was established to manage the rural credit cooperatives in Guangzhou. In 2006, with the approval of CBRC, Guangzhou Rural Credit Cooperative Union, 14 rural credit cooperatives, and 10 rural credit cooperative unions at district and county level in Guangzhou established Guangzhou Rural Credit Cooperative ( ) upon completion of the corporate reform into a unified legal person. Guangzhou Rural Credit Cooperative was registered at the Administration for Industry and Commerce of Guangzhou and established on October 27, 2006. In July 2009, with the approval of the Guangdong Provincial People’s Government, Guangzhou Rural Credit Cooperative underwent restructuring and, with approved eligible members of Guangzhou Rural Credit Cooperative and other share subscribers as promoters (i.e., 727 corporate shareholders and 28,936 individual shareholders), Guangzhou Rural Commercial Bank Co., Ltd. ( ) was incorporated. With the approval of CBRC, our Bank completed its registration as a joint stock limited company at the Administration for Industry and Commerce of Guangzhou on December 9, 2009, with our Head Office in Guangzhou. Key milestones in our history are summarized as follows. Year Event November 1952 The first rural credit cooperative in Guangzhou was established. -

Urgent Action

UA: 190/17 Index: ASA 17/6887/2017 China Date: 7 August 2017 URGENT ACTION SIX ACTIVISTS DETAINED FOR LIU XIAOBO MEMORIAL Wei Xiaobing, He Lin, Liu Guangxiao, Li Shujia, Wang Meiju and Qin Mingxin have been criminally detained on suspicion of “assembling a crowd to disturb social order” after they held a seaside memorial for deceased Nobel Peace Prize laureate Liu Xiaobo in Jiangmen, Guangdong province. Guangdong activists Wei Xiaobing (aka “1.3 billion citizens”), He Lin, Liu Guangxiao, Li Shujia, Wang Meiju and Qin Mingxin have been taken away by police and had their homes raided several days after they conducted a seaside memorial for Liu Xiaobo on 19 July 2017 to mark the seventh day after the Nobel Peace Prize’s death. Broadcasted live by Hong Kong Cable TV, the activists brought a chair, some flowers and chanted slogans, including “Liu Xiaobo, Rest in Peace” and “Free Liu Xia”, to pay tribute to Liu Xiaobo and support his wife Liu Xia during the memorial. They later uploaded the video and photos of the action on social media. All six activists are being criminally detained at the Xinhui District Detention Centre in Jiangmen city, Guangdong province on suspicion of “assembling a crowd to disturb social order”. According to Wei Xiaobing’s lawyer, who met with him on 26 July 2017, he was taken away from his home in Jieshi Town, Lufeng city, Guangdong province, at around 1am on 22 July. Later that same morning, at around 4am, He Lin, Liu Guangxiao and Li Shujia were also taken away from their homes by police from Xinhui District, Jiangmen city. -

National Reports on Wetlands in South China Sea

United Nations UNEP/GEF South China Sea Global Environment Environment Programme Project Facility “Reversing Environmental Degradation Trends in the South China Sea and Gulf of Thailand” National Reports on Wetlands in South China Sea First published in Thailand in 2008 by the United Nations Environment Programme. Copyright © 2008, United Nations Environment Programme This publication may be reproduced in whole or in part and in any form for educational or non-profit purposes without special permission from the copyright holder provided acknowledgement of the source is made. UNEP would appreciate receiving a copy of any publication that uses this publicationas a source. No use of this publication may be made for resale or for any other commercial purpose without prior permission in writing from the United Nations Environment Programme. UNEP/GEF Project Co-ordinating Unit, United Nations Environment Programme, UN Building, 2nd Floor Block B, Rajdamnern Avenue, Bangkok 10200, Thailand. Tel. +66 2 288 1886 Fax. +66 2 288 1094 http://www.unepscs.org DISCLAIMER: The contents of this report do not necessarily reflect the views and policies of UNEP or the GEF. The designations employed and the presentations do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of UNEP, of the GEF, or of any cooperating organisation concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area, of its authorities, or of the delineation of its territories or boundaries. Cover Photo: A vast coastal estuary in Koh Kong Province of Cambodia. Photo by Mr. Koch Savath. For citation purposes this document may be cited as: UNEP, 2008. -

Vertical Metal F'ile Cabinets

Barcode:3827074-03 C-570-111 INV - Investigation - CHINESE EXPORTERS AND PRODUCERS OF VERTICAL METAL F'ILE CABINETS Best Beaufy Furniture Co., Ltd. Feel Life Co., Ltd. Lianping Industry Zone, Dalingshan Town Room 202, Deweisen Building Dongguan, Guangdon g, 523809 Nanshan District, Shenzhen Tel: +86 769-85623639 1sf ¡ +86 7 55-66867080-8096 Fax: +86 769-85628609 Fax: +86 755-86146992 Email: N/A Email : [email protected] Website: Website : www. feellife. com www. d gbestbeauty. company. weiku. com/ Fujian lvyer Industrial Co., Ltd. Chung \ilah Steel Furniture Factory Co., Yangxia Village, Guhuai Town Lrd. Changle, Fujian, 350207 Block A,7lF Chinaweal Centre Tel: +86 59128881270 414-424 Jaffe Road, Wanchai Fax: +86 59128881315 Hong Kong Email : nancy @flivyer. com Tel: +85 228930378 Website : www. ivyer.net. cnl Fax: +85 228387626 Email: N/A Fuzhou Nu Deco Crafts Co., Ltd. Website : http ://chungwah. com.hk/ 1306 Xinxing Building No. 41, Bayiqi Mid. Road Concept Furniture (Anhui) Co.' Ltd. Fuzhou, Fujian, 350000 Guangde Economic and Technical Tel: +86 591-87814422 Developm ent Zone, Guangde County P¿¡; +86 591-87814424 Anhui, Xuancheng, 242200 Email: [email protected] Tel: 865-636-0131 Website : http :/inu-deco.cnl Fax: 865-636-9882 Email: N/A Fuzhou Yibang Furniture Co., Ltd. Website: N/A No. 85-86 Building Changle Airport Industrial Zone Dong Guan Shing Fai X'urniture Hunan Town, Changle 2nd Industrial Area Fujian, Fuzhou, 350212 Shang Dong Administrative Dist. fsf; +86 591-28637056 Qishi, Dongguan, Guangdong, 523000 Fax: +86 591-22816378 Tel: +86 867592751816 Email: N/A Fax: N/A V/ebsite : htþs ://fi yb. -

Cereal Series/Protein Series Jiangxi Cowin Food Co., Ltd. Huangjindui

产品总称 委托方名称(英) 申请地址(英) Huangjindui Industrial Park, Shanggao County, Yichun City, Jiangxi Province, Cereal Series/Protein Series Jiangxi Cowin Food Co., Ltd. China Folic acid/D-calcium Pantothenate/Thiamine Mononitrate/Thiamine East of Huangdian Village (West of Tongxingfengan), Kenli Town, Kenli County, Hydrochloride/Riboflavin/Beta Alanine/Pyridoxine Xinfa Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd. Dongying City, Shandong Province, 257500, China Hydrochloride/Sucralose/Dexpanthenol LMZ Herbal Toothpaste Liuzhou LMZ Co.,Ltd. No.282 Donghuan Road,Liuzhou City,Guangxi,China Flavor/Seasoning Hubei Handyware Food Biotech Co.,Ltd. 6 Dongdi Road, Xiantao City, Hubei Province, China SODIUM CARBOXYMETHYL CELLULOSE(CMC) ANQIU EAGLE CELLULOSE CO., LTD Xinbingmaying Village, Linghe Town, Anqiu City, Weifang City, Shandong Province No. 569, Yingerle Road, Economic Development Zone, Qingyun County, Dezhou, biscuit Shandong Yingerle Hwa Tai Food Industry Co., Ltd Shandong, China (Mainland) Maltose, Malt Extract, Dry Malt Extract, Barley Extract Guangzhou Heliyuan Foodstuff Co.,LTD Mache Village, Shitan Town, Zengcheng, Guangzhou,Guangdong,China No.3, Xinxing Road, Wuqing Development Area, Tianjin Hi-tech Industrial Park, Non-Dairy Whip Topping\PREMIX Rich Bakery Products(Tianjin)Co.,Ltd. Tianjin, China. Edible oils and fats / Filling of foods/Milk Beverages TIANJIN YOSHIYOSHI FOOD CO., LTD. No. 52 Bohai Road, TEDA, Tianjin, China Solid beverage/Milk tea mate(Non dairy creamer)/Flavored 2nd phase of Diqiuhuanpo, Economic Development Zone, Deqing County, Huzhou Zhejiang Qiyiniao Biological Technology Co., Ltd. concentrated beverage/ Fruit jam/Bubble jam City, Zhejiang Province, P.R. China Solid beverage/Flavored concentrated beverage/Concentrated juice/ Hangzhou Jiahe Food Co.,Ltd No.5 Yaojia Road Gouzhuang Liangzhu Street Yuhang District Hangzhou Fruit Jam Production of Hydrolyzed Vegetable Protein Powder/Caramel Color/Red Fermented Rice Powder/Monascus Red Color/Monascus Yellow Shandong Zhonghui Biotechnology Co., Ltd. -

Exploring Economic Benefits of Sister Cities: Prince George and Jiangmen

Exploring Economic Benefits of Sister Cities: Prince George and Jiangmen 1100 Patricia Blvd. Prince George, BC, Canada V2L 3V9 Tel. 250.561.7633 www.investprincegeorge.ca Exploring Economic Benefits of Sister Cities: Prince George and Jiangmen Jiangmen 2/28/2014 Partnerships for Prosperity The aim of sister cities is to foster communication across borders, promote cultural, educational, and sporting exchange, initiate collaborative research, and increase tourism and trade between the two cities. Page 1 Exploring Economic Benefits of Sister Cities: Prince George and Jiangmen Table of Contents 1. Exploring Economic benefits of sister cities: Prince George and Jiangmen……………………3 2. The city of Jiangmen…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………4-6 3. The city of Prince George……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………… 7-8 4. Potential export products to Jiangmen………………………………………………………………………………………… 9-10 5. Opportunities for Prince George Manufacturing sector………….……………….………………………………… 11 6. Opportunities for Prince George Construction sector………………………………………………………………… 12 7. Opportunities for Prince George Healthcare and social assistance sector……..……………… 13 8. Opportunities for Prince George Scientific and Professional services sector…………….14-15 9. Opportunities for Prince George Education Services sector…………………………………………………… 16 10. Opportunities for Prince George Agriculture and Forestry sector………………………………… 17-18 11. Opportunities for Prince George Information, Culture, and Recreation sector……………… 19 12. Opportunities for Prince George Mining, -

Cantonese Connections the Origins of Australia’S Early Chinese Migrants

GENEALOGY Fannie Chok See, James Choy Hing and their three children, Dorothy May, James and Pauline, in Sydney, 1905. James Choy Hing was from Ngoi Sha village in Chungshan. Image courtesy of the National Archives of Australia: SP244/2, N1950/2/4918 Cantonese connections The origins of Australia’s early Chinese migrants By Dr Kate Bagnall For Australians researching their Chinese family history, discovering their ancestors’ hometown and Chinese name is signifi cant. n a quiet residential street in the inner-city Sydney Temple in Retreat Street, Alexandria, was opened a few suburb of Glebe, on a large grassy block that years later, in 1909. In contrast to the Glebe temple, the stretches down towards the harbour, sits the Sze Yiu Ming Temple is tucked away at the end of a double Yup Kwan Ti Temple. Built between 1898 and row of terraces, also owned by the Yiu Ming Society, all of 1904, the Sze Yup Temple is one of two heritage- which are now surrounded by busy commercial buildings Ilisted temples in Sydney. T e second, the Yiu Ming and apartment blocks. Uncovering the past 43 GENEALOGY Family grouped in front of their home in New South Wales, circa 1880–1910. Image courtesy of the State Library of Victoria In the early years of the 20th century, when the two temples were built, the Chinese population in Sydney and surrounding suburbs was just over 3800, of whom about 200 were women and girls. In Australia as a whole, there were about 33,000 people of Chinese ancestry. Chinese communities around Australia were diverse – in occupation, politics, class and religion, as well as in dialect and hometown. -

SCHOLAR EDUCATION GROUP 思 考 樂 教 育 集 團 (Incorporated in the Cayman Islands with Limited Liability) (Stock Code: 1769)

Hong Kong Exchanges and Clearing Limited and The Stock Exchange of Hong Kong Limited take no responsibility for the contents of this announcement, make no representation as to its accuracy or completeness and expressly disclaim any liability whatsoever for any loss howsoever arising from or in reliance upon the whole or any part of the contents of this announcement. SCHOLAR EDUCATION GROUP 思 考 樂 教 育 集 團 (Incorporated in the Cayman Islands with limited liability) (Stock Code: 1769) CONNECTED TRANSACTIONS TENANCY AGREEMENTS THE NOVEMBER 2020 CRV AGREEMENTS The Group is continuously identifying suitable premises for its business expansion. The Board is pleased to announce that, further to the December 2019 CRV Agreements, the April 2020 CRV Agreement and the May 2020 CRV Agreement, the Group has again cooperated with CR Vanguard (a state-owned enterprise with nearly 220,000 employees, and a leading retailer and operator of commercial properties with a mature, extensive business network of over 3,100 retail stores under its ownership in more than 240 cities across the PRC), and entered into the November 2020 CRV Agreements for the rental of four premises in (i) Huadu District, Guangzhou, (ii) Xiangzhou District, Zhuhai, (iii) Torch Hi-Tech Industrial Development Zone, Zhongshan and (iv) Shunde District, Foshan, respectively, with a view to developing and operating new learning centres. The Board considers that such premises would be conducive to the Group in strengthening its market leading presence in Guangdong-Hong Kong-Macau Greater Bay Area, and the entering into of the November 2020 CRV Agreements signify the development of the Group’s strategic cooperation with CREG (a substantial shareholder of the Company) and CR Vanguard. -

Understanding Land Subsidence Along the Coastal Areas of Guangdong, China, by Analyzing Multi-Track Mtinsar Data

remote sensing Article Understanding Land Subsidence Along the Coastal Areas of Guangdong, China, by Analyzing Multi-Track MTInSAR Data Yanan Du 1 , Guangcai Feng 2, Lin Liu 1,3,* , Haiqiang Fu 2, Xing Peng 4 and Debao Wen 1 1 School of Geographical Sciences, Center of GeoInformatics for Public Security, Guangzhou University, Guangzhou 510006, China; [email protected] (Y.D.); [email protected] (D.W.) 2 School of Geosciences and Info-Physics, Central South University, Changsha 410083, China; [email protected] (G.F.); [email protected] (H.F.) 3 Department of Geography, University of Cincinnati, Cincinnati, OH 45221-0131, USA 4 School of Geography and Information Engineering, China University of Geosciences (Wuhan), Wuhan 430074, China; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +86-020-39366890 Received: 6 December 2019; Accepted: 12 January 2020; Published: 16 January 2020 Abstract: Coastal areas are usually densely populated, economically developed, ecologically dense, and subject to a phenomenon that is becoming increasingly serious, land subsidence. Land subsidence can accelerate the increase in relative sea level, lead to a series of potential hazards, and threaten the stability of the ecological environment and human lives. In this paper, we adopted two commonly used multi-temporal interferometric synthetic aperture radar (MTInSAR) techniques, Small baseline subset (SBAS) and Temporarily coherent point (TCP) InSAR, to monitor the land subsidence along the entire coastline of Guangdong Province. The long-wavelength L-band ALOS/PALSAR-1 dataset collected from 2007 to 2011 is used to generate the average deformation velocity and deformation time series. Linear subsidence rates over 150 mm/yr are observed in the Chaoshan Plain. -

Surface Deformation Evolution in the Pearl River Delta Between 2006 and 2011 Derived from the ALOS1/PALSAR Images

Surface Deformation Evolution in the Pearl River Delta between 2006 and 2011 derived from the ALOS1/PALSAR images Genger Li Guangdong Institute of Surveying and Mapping of Geology Guangcai Feng ( [email protected] ) Central South University Zhiqiang Xiong Central South University Qi Liu Central South University Rongan Xie Guangdong Institute of Surveying and Mapping of Geology Xiaoling Zhu Guangdong Institute of Surveying and Mapping of Geology Shuran Luo Central South University Yanan Du Guangzhou University Full paper Keywords: Pearl River Delta, natural evolution, surface subsidence, SBAS-InSAR Posted Date: October 30th, 2020 DOI: https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-32256/v2 License: This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Read Full License Version of Record: A version of this preprint was published on November 26th, 2020. See the published version at https://doi.org/10.1186/s40623-020-01310-2. Page 1/22 Abstract This study monitors the land subsidence of the whole Pearl River Delta (PRD) (area: ~40,000 km2) in China using the ALOS1/PALSAR data (2006-2011) through the SBAS-InSAR method. We also analyze the relationship between the subsidence and the coastline change, river distribution, geological structure as well as the local terrain. The results show that (1) the land subsidence with the average velocity of 50 mm/year occurred in the low elevation area in the front part of the delta and the coastal area, and the area of the regions subsiding fast than 30 mm/year between 2006 and 2011 is larger than 122 km2; (2) the subsidence order and area estimated in this study are both much larger than that measured in previous studies; (3) the areas along rivers suffered from surface subsidence, due to the thick soft soil layer and frequent human interference; (4) the geological evolution is the intrinsic factor of the surface subsidence in the PRD, but human interference (reclamation, ground water extraction and urban construction) extends the subsiding area and increases the subsiding rate. -

Pearl River Delta Demonstration Project

Global Water Partnership (China) WACDEP Work Package Five outcome report Pearl River Delta Demonstration Project Pearl River Water Resources Research Institution December 201 Copyright @ 2016 by GWP China Preface The Pearl River Delta (PRD) is the low-lying area surrounding the Pearl River estuary where the Pearl River flows into the South China Sea. It is one of the most densely urbanized regions in the world and one of the main hubs of China's economic growth. This region is often considered an emerging megacity. The PRD is a megalopolis, with future development into a single mega metropolitan area, yet itself is at the southern end of a larger megalopolis running along the southern coast of China, which include Hong Kong, Macau and large metropolises like Chaoshan, Zhangzhou-Xiamen, Quanzhou-Putian, and Fuzhou. It is also a region which was opened up to commerce and foreign investment in 1978 by the central government of the People’s Republic of China. The Pearl River Delta economic area is the main exporter and importer of all the great regions of China, and can even be regarded as an economic power. In 2002, exports from the Delta to regions other than Hong Kong, Macau and continental China reached USD 160 billion. The Pearl River Delta, despite accounting for just 0.5 percent of the total Chinese territory and having just 5 percent of its population, generates 20 percent of the country’s GDP. The population of the Pearl River Delta, now estimated at 50 million people, is expected to grow to 75 million within a decade.