Stock Market Response to New Product Launch and the Respective Advertising Strategy an Event Study Analysis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Game Streaming Service Onlive Coming to Tablets 8 December 2011, by BARBARA ORTUTAY , AP Technology Writer

Game streaming service OnLive coming to tablets 8 December 2011, By BARBARA ORTUTAY , AP Technology Writer high-definition gaming consoles such as the Xbox 360 and the PlayStation 3. But when they are streamed, the games technically "play" on OnLive's remote servers and are piped onto players' phones, tablets or computers. OnLive users in the U.S. and the U.K. will be able This product image provided by OnLive Inc, shows to use the mobile and tablet service. Games tablets displaying a variety of games using the OnLive available include "L.A. Noire" from Take-Two game controller. OnLive Inc. said Thursday, Dec. 8, Interactive Software Inc. and "Batman: Arkham 2011, that it will now stream console-quality games on City." The games can be played either using the tablets and phones using a mobile application. (AP gadgets' touch screens or via OnLive's game Photo/OnLive Inc.) controller, which looks similar to what's used to play the Xbox or PlayStation. Though OnLive's service has gained traction (AP) -- OnLive, the startup whose technology among gamers, it has yet to reach a mass market streams high-end video games over an Internet audience. connection, is expanding its service to tablets and mobile devices. ©2011 The Associated Press. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, OnLive Inc. said Thursday that it will now stream rewritten or redistributed. console-quality games on tablets and phones using a mobile application. Users could already stream such games using OnLive's "microconsole," a cassette-tape sized gadget attached to their TV sets, or on computers. -

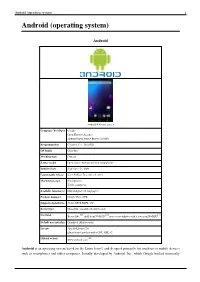

Android (Operating System) 1 Android (Operating System)

Android (operating system) 1 Android (operating system) Android Android 4.4 home screen Company / developer Google Open Handset Alliance Android Open Source Project (AOSP) Programmed in C (core), C++, Java (UI) OS family Unix-like Working state Current Source model Open source with proprietary components Initial release September 23, 2008 Latest stable release 4.4.2 KitKat / December 9, 2013 Marketing target Smartphones Tablet computers Available language(s) Multi-lingual (46 languages) Package manager Google Play, APK Supported platforms 32-bit ARM, MIPS, x86 Kernel type Monolithic (modified Linux kernel) [1] [2] [3] Userland Bionic libc, shell from NetBSD, native core utilities with a few from NetBSD Default user interface Graphical (Multi-touch) License Apache License 2.0 Linux kernel patches under GNU GPL v2 [4] Official website www.android.com Android is an operating system based on the Linux kernel, and designed primarily for touchscreen mobile devices such as smartphones and tablet computers. Initially developed by Android, Inc., which Google backed financially Android (operating system) 2 and later bought in 2005, Android was unveiled in 2007 along with the founding of the Open Handset Alliance: a consortium of hardware, software, and telecommunication companies devoted to advancing open standards for mobile devices. The first publicly available smartphone running Android, the HTC Dream, was released on October 22, 2008. The user interface of Android is based on direct manipulation, using touch inputs that loosely correspond to real-world actions, like swiping, tapping, pinching and reverse pinching to manipulate on-screen objects. Internal hardware such as accelerometers, gyroscopes and proximity sensors are used by some applications to respond to additional user actions, for example adjusting the screen from portrait to landscape depending on how the device is oriented. -

Listing Statement Cse Form 2A Nextech Ar Solutions Corp

LISTING STATEMENT CSE FORM 2A NEXTECH AR SOLUTIONS CORP. October 24, 2018 TABLE OF CONTENTS GLOSSARY 1 CORPORATE STRUCTURE 3 GENERAL DEVELOPMENT OF THE BUSINESS 4 USE OF AVAILABLE FUNDS 18 SELECTED CONSOLIDATED FINANCIAL INFORMATION 19 DIVIDENDS 20 MANAGEMENT’S DISCUSSION AND ANALYSIS 20 MARKET FOR SECURITIES 20 CONSOLIDATED CAPITALIZATION 21 OPTIONS TO PURCHASE SECURITIES 21 DESCRIPTION OF SECURITIES 22 ESCROWED SECURITIES 23 PRINCIPAL SHAREHOLDERS 24 DIRECTORS AND OFFICERS 24 CAPITALIZATION 28 EXECUTIVE COMPENSATION 32 INDEBTEDNESS OF DIRECTORS AND EXECUTIVE OFFICERS 34 RISK FACTORS 34 PROMOTERS 38 LEGAL PROCEEDINGS 38 INTEREST OF MANAGEMENT AND OTHERS IN MATERIAL TRANSACTIONS 39 AUDITORS, TRANSFER AGENT AND REGISTRAR 39 MATERIAL CONTRACTS 39 INTERESTS OF EXPERTS 39 OTHER MATERIAL FACTS 40 FINANCIAL STATEMENTS 40 SCHEDULE “A-1” – FINANCIAL STATEMENTS SCHEDULE “A-2” – CARVE OUT FINANCIAL STATEMENTS SCHEDULE “B” – MANAGEMENT DISCUSSION AND ANALYSIS GLOSSARY In this Listing Statement, unless otherwise defined herein or unless there is something in the subject matter inconsistent therewith, the following terms have the respective meanings set out below, words importing the singular number include the plural and vice versa and words importing any gender include all genders. “2D” means two dimensional. “3D” means three dimensional. “adMob” is Google’s advertising platform for promoting and monetizing mobile apps. adMob allows app developers to promote their apps through in-app ads, monetize their apps by enabling in-app advertising, and provide intelligent insights through Google Analytics. “Android” means an open-source operating system used for smartphones and tablet computers. “app” means an application, especially as downloaded by a user to a mobile device. -

Cutting the Cable Cord

3/11/2021 The views, opinions, and information expressed during this • March 11, 6:30-7:30 PM webinar are those of the presenter and are not the views or opinions of the Newton Public Library. The Newton Public Library • FREE! NO REGISTRATION REQUIRED makes no representation or warranty with respect to the webinar or any information or materials presented therein. Users of webinar materials should not rely upon or construe the Thinking of cutting the cord? What are your options? ChromeCast information or resource materials contained in this webinar as Why and why not do it, Apple TV, Roku alternatives and more sources of entertainment. Sling, Hulu, Netflix legal or other professional advice and should not act or fail to act To log in live from home go to: based on the information in these materials without seeking the services of a competent legal or other specifically specialized https://kslib.zoom.us/j/561178181 professional. Watch the recorded presentation anytime after the 15th or Recorded https://kslib.info/1180/Digital-Literacy---Tech-Talks Presenter: Nathan, IT Supervisor, at the Newton Public Library 1. Protect your computer • A computer should always have the most recent updates installed for spam filters, anti-virus and anti-spyware software and http://www.districtdispatch.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/03/triple_play_web.png a secure firewall. http://cdn.greenprophet.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/04/frying-pan-kolbotek-neoflam-560x475.jpg What is “Cutting the Cord” Cable TV Cord Cutting (verb): The act of canceling your cable or Cable is the immediate answer satellite subscription in favor of a more affordable and obvious choice with the most television viewing option. -

Considerations for a Real Time Broadband Delivered Interactive Gaming Service

CONSIDERATIONS FOR A REAL TIME BROADBAND DELIVERED INTERACTIVE GAMING SERVICE Charles H. Jablonski VP Operations, OnLive Inc Abstract Introduction The march of enabling technology and the Real Time graphics intensive applications, continued improvement in broadband such has “first person shooter games” have connectivity and availability have enabled presented challenges in being server/cloud many services and products to be delivered to based because of the inherent roundtrip end consumers and enterprises as various latencies. compressed data and media files. The success of services such as video on demand and This paper will describe an approach that “ultra” high speed broadband are well known provides the ability not only to deliver real and their effects have caused consumer tastes time games but also that is able to deliver any and expectation to evolve accordingly. graphics intensive application over existing broadband infrastructure. In few short years linear packaged media has evolved from a shrink wrap retail point of The approaches taken to provide the sale product to a anywhere, anytime, almost necessary low latency compression, server any device availability. At times the business and data center architecture, integrating into issues have been far more daunting that the exiting carrier and ISP data infrastructures as technological, but one undisputed fact is that well as the impacts of “last mile” ISP (DSL the consumer continues to be more and Cable) considerations as well as the demanding and the expectations of required performance -

CES Report 2015 Finalv2 11915

VIRTUAL REALITY TELEVISIONS TOP TRENDS HEADSETS, CONTENT AND BIGGER, UHD, WEARABLES, MOBILITY DEVELOPERS GET BETTER, AND THE INTERNET OF TOGETHER SMARTER EVERYTHING www.etcenter.org| January 2015 2015 International CES CES2015: From Dreams to Reality Mobile Photo Credit: The Everett Collection. Everett The Credit: Photo Is the Car the New Media Center? 2015 International CES ETC@USC TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 Introduction 2 Executive Summary 3 Keynotes CATEGORIES 4 Virtual and Augmented Reality 5 TV: UHD, HDR & Smart TV 6 Automotive 7 Smart Home & Internet of Things 8 Sensors & Wearables 9 Mobile 10 Games 11 High Resolution Audio 12 New, Notable & Interesting 13 Closing Perspective Disclaimer: The opinions expressed in this report do not represent the thoughts, intentions, plans or strategies of any of ETC’s sponsors, people, institutions or organizations that may or may not be related to the ETC. This report may include links to other resources operated by third parties. These are provided as a convenience to our readers for verification of the information or opinion contained therein. We are not responsible for the content on any other sites or any products or services that may be offered through other sites, and the inclusion of such links does not signify any endorsement of, affiliation with, or sponsorship of the other site or organization. Some photos enclosed herein courtesy of CEA or the vendor being discussed. ETC asserts no rights to such photographs. ©2015 Entertainment Technology Center@USC 2015 International CES ETC@USC Covering CES Kenneth Williams, Executive Director & CEO EDITORIAL The following report is the Entertainment Technology Center’s post show Rob Scott, ETCentric Editor analysis of the 2015 International CES. -

Remote Gaming on Resource Constrained Devices

REMOTE GAMING ON RESOURCE CONSTRAINED DEVICES by Waazim Reza A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of The College of Engineering and Computer Science in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science Florida Atlantic University Boca Raton, Florida December 2010 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to express my gratitude to my advisor, Dr. Hari Kalva, for his support and direction. He has been patient, encouraging and a great source of motivation throughout my tenure here at FAU. He has inspired me from his calm and serene demeanor even in toughest of situations. His technical and editorial advice was essential to the completion of this master’s thesis and has taught me innumerable lessons and insights. I would like to sincerely thank my committee members Dr. Oge Marques and Dr. Daniel Raviv for their valuable comments, suggestions and input to the thesis. Thanks a lot for your patience and time. I would like to thank Dr. Thanh Tran from Texas Instruments, for the initial idea and the motivation for the project. Also, Richard Kaufman helped a lot in the implementation of the game. I would like to thank all my colleagues - Sagar, Velibor, Rafael and others in Multimedia lab at FAU with whom I had technical discussions and collaborated on multiple projects. Thanks to Lakitosh, Aneesh and Baishali for being like a family and supporting me. iii I express my deepest love and gratitude to my parents U Abdul Salam and Zainaba, for their unparalleled and unconditional support throughout my life. My brothers Reza and Zaqie, have been a great support. -

How Is Your Business Powering up for the Next Video Gaming Challenge?

How is your business powering up for the next video gaming challenge? Media & Entertainment 02 About this report Following an era of unprecedented growth, the video game industry faces a number of challenges. EY conducted proprietary research to better understand the industry’s issues and identify solutions. We surveyed nearly 240 global video gaming senior executives, spanning independent developers to the world’s largest game publishers, and with revenues ranging from US$1m to well over US$1b. Survey and study overview Seniority of role Role function Methodology • Survey of 236 gaming executives CFO Finance CIO Partnerships Procurement 2% 2% (C-suite, directors and above) 8% 3% and supply 2% COO Director HR 5% 33% • Conducted: March – May 2019 8% Support and Production analytics 9% 29% CMO • Geographies: worldwide 8% (North America, Asia, Europe) Marketing • Companies: various segments based SVP 13% 9% on revenue size (US$1m–more than US$1b) Design Board VP IT and cyber 22% member CEO 13% 15% 9% 10% Company size Geography More than US$1b South Africa US$500m–US$1b China 1% 4% 11% 16% US$100m– US$1m–US$5m US$500m 27% 12% UK 13% Japan 17% Canada 11% US$5m–US$20m South Korea US$20m–US$100m US 18% 15% 38% 15% 03 Introduction It’s been a period of jackpot growth and earnings for the video game industry. In the last five years alone, video gaming revenues have almost doubled. And in the next two years, the industry is forecast to be the fastest-growing media and entertainment (M&E) sector after subscription video on demand (SVOD) and online display advertising.1,2 But video game companies are entering a new era — one of EY recently conducted a survey of nearly 240 global video increased innovation and broadening popularity, yet one gaming senior executives, spanning independent developers to of rising risk; escalating content costs; and new, disruptive the world’s largest game publishers, and with revenues ranging business models. -

Spencer L. Bevis. Software Emulation and the Video Game Community: a Web Content Analysis of User Needs

Spencer L. Bevis. Software Emulation and the Video Game Community: A Web Content Analysis of User Needs. A Master’s Paper for the M.S. in L.S. degree. April, 2019. 76 pages. Advisor: Megan Winget. In the past decade, archives have utilized emulation to preserve older pieces of software including video games and make them accessible to patrons. However, recent literature neglects user needs for emulated software in archives. Using web content analysis, this study examines the text of nearly 1,200 online comments, threads, and forum posts about software emulation from four different websites. The findings suggest that audiences are keenly aware of software emulation but not of emulation as a way to preserve video games. It also found that user needs are often unique or even contradictory, and much user attention is paid to the visual quality of emulation systems as well as the quality of the emulated experience. The author suggests a number of policy proposals for libraries and archives that argue greater public input is necessary in the creation and development of systems that preserve software through the process of emulation. Headings: Information needs Digital preservation -- Video games Digital preservation -- Software Internet research -- Content analysis SOFTWARE EMULATION AND THE VIDEO GAME COMMUNITY: A WEB CONTENT ANALYSIS OF USER NEEDS by Spencer L. Bevis A Master’s paper submitted to the faculty of the School of Information and Library Science of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Library Science. Chapel Hill, North Carolina April 2019 Approved by _______________________________________ Megan Winget 1 Part 1: Introduction As a popular entertainment medium, video games are a cultural powerhouse. -

Why and Why Not Do It, Alternatives and More Sources of Entertainment

11/20/2015 Class Objective • November 19, 5-6 PM • FREE! NO REGISTRATION REQUIRED Inform the participant and Test • come to Newton and participate Drive Laptops, Tablets and with a live audience. What are your options? ChromeCast devices that offer Thinking of cutting the cord? ChromeCast Why and why not do it, Apple TV, Roku opportunities for online alternatives and more sources of entertainment. Sling, Hulu, Netflix entertainment including movies To log in live from home go to: and games. Just in time for the https://kanren.zoom.us/j/561178181 Watch the recorded presentation anytime after the 15th gift giving season! Presenter: Nathan, IT Supervisor, at the Newton Public Library CORRECTION: cox cable finally replied Cable TV They are the immediate to me in an email. Sent: Thursday, November 19, 2015 7:41 PM answer and obvious To: 'Nathan Carr' choice with the most Subject: RE: Tech Treats Class to the public subscribers and most Hi Nathan! Does this help: channels and options. Cox Communications is a broadband communications and entertainment company, providing Cable is the first and advanced digital video, Internet, telephone and home security and automation services over last stop for home its own nationwide IP network. The third-largest U.S. cable company, Cox serves approximately 6 million residences and businesses. Cox Business is a facilities-based entertainment for most provider of voice, video and data solutions for commercial customers, and Cox Media is a full-service provider of national and local cable spot and digital media advertising. Cox is people of the last known for its pioneering efforts in cable telephone and commercial services, industry- decade leading customer care and its outstanding workplaces. -

Connected Game Console Update

Connected Game Console Update By Pietro Macchiarella, Research Analyst 4Q 2010 Synopsis Connected Consoles among Console Owners This report focuses on the current generation Console Owners with Internet-Connected Consoles of game consoles (Sony PlayStation 3, 70% Among All Console Owners Xbox 360, Nintendo Wii). It analyzes Among Owners of Current Generation current market Only (PS3, XBOX 360, Wii) dynamics, business models, monetization Owners opportunities, and future sales forecasts. The report also explores their gaming features and entertainment content Consoles with Connected distribution features as Console of Percentage these consoles become entertainment hubs. 0% Q3 2007 Q3 2008 Q4 2008 Q4 2009 Q2 2010 Q3 2010 Sources: DMH II (Q3 2007), TV2.0 (Q3 2008), DME (Q4 2008), AEOV (Q4 2009), DME II (Q2 2010), CDP3Q (Q3 2010) © 2010 Parks Associates Publish Date: 4Q 10 “Game consoles have become powerful entertainment hubs that provide much more than gaming. Their convenient location in people’s living rooms makes them a privileged device for the distribution of entertainment content,” said Pietro Macchiarella, Research Analyst at Parks Associates. “Today, almost two-thirds of consoles are connected to the Internet. Their huge movie and TV libraries, and their flexibility in accessing premium online content such as Netflix, Hulu, and VUDU, are making these devices primary contenders in the monetization of online entertainment distribution.” Contents Connected Game Console Update – Dashboard 1.0 Notes on Methodology and Report Focus 1.1 Data Sources 1.2 Scope of Report 1.3 Definitions 2.0 Game Consoles: a Market Overview 2.1 The Current Generation of Consoles 2.2 Sales, Market Shares and Penetration 2.3 New User Interfaces - Motion Controllers and Kinect 2.4 Key Consumer Findings 3.0 Connected Consoles: Gaming 3.1 Growth of Connected Game Consoles 3.2 Online Multiplayer Gaming 3.3 Digital Distribution: Games and DLC 3.4 Virtual Worlds and Avatars 3.5 Game Advertising © 2010 Parks Associates. -

Reconfiguring Businesses, Players, and Roles

Reconfiguring Businesses, Players, and Roles Rubik’s Cube® used by permission of Rubik’s Brand Ltd. www.rubiks.com The Story Is Just Beginning These stories are about a changing world where legacy and incumbent organizations are being challenged by a new wave of providers who have compelling narratives that speak to our own changing experiences at work, at home, and in society at large. This examine the transition and restructuring of trust and expectations that are taking place in all sectors, public and private, personal and social. This restructuring is the compelling narrative of our time. Three strategic shifts come through the analysis: • Legacy ‘horizontal’ providers who seek to own a customer and service all their needs are being out-maneuvered by more agile, and focused ‘vertical’ providers who do one thing, in more places, at scale; we call the resulting competitive market dynamic compression. • We are witnessing massive regime change, with legacy organizations leadership teams reaching limits of the horizontal model, while the new Founders of the Vertical are building out into market adjacencies due to a combination of long-term vision, canny de-leveraging of risk, and aggressive real-time externalization of business processes to the ecosystem. • These two trends ride the rails of changing usage patterns that are not restricted to ‘GenX’ or ‘users’ in the conventional sense. There’s a reason what so many incumbent companies are losing their way: they are focused on existing usage patterns that are being replaced every nine months. They miss the strong correlation between the rate of innovation/iteration, and scale.