Spencer L. Bevis. Software Emulation and the Video Game Community: a Web Content Analysis of User Needs

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

![General Processor Emulator [Genproemu]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/9533/general-processor-emulator-genproemu-79533.webp)

General Processor Emulator [Genproemu]

Special Issue - 2015 International Journal of Engineering Research & Technology (IJERT) ISSN: 2278-0181 NCRTS-2015 Conference Proceedings General Processor Emulator [GenProEmu] Bindu B, Shravani K L, Sinchana Hegde Guide: Mr.Aditya Koundinya B, Asst. Prof Computer Science Department Jyothy Institute Of Technology Tatguni,Bangalore-82 Abstract - GenProEmu is an interactive computer emulation programmable device that accepts digital data as input, package in which the user specifies the details of the CPU to processes it according to instructions stored in its memory, be emulated, including the register set, memory, the and provides results as output. It is an example of microinstruction set, machine instruction set, and assembly sequential digital logic, as it has internal memory. language instructions. Users can write machine or assembly Microprocessors operate on numbers and symbols language programs and run them on the CPU they’ve created. represented in the binary numeral system. GenProEmu simulates computer architectures at the register- transfer level. That is, the basic hardware units from which a The fundamental operation of most CPUs, regardless of the hypothetical CPU is constructed consist of registers and physical form they take, is to execute a sequence of stored memory (RAM). The user does not need to deal with instructions called a program. The instructions are kept in individual transistors or gates on the digital logic level of a some kind of computer memory. There are three steps that machine. nearly all CPUs use in their operation: fetch, decode, and execute. 1. INTRODUCTION Fetch- An embedded system is a computer system with a The first step, fetch, involves retrieving an instruction dedicated function within a larger mechanical or electrical (which is represented by a number or sequence of numbers) system, often with real-time computing constraints. -

Aviva for Terminal Server(NA)

Aviva Solutions – Unleashing the Power of Enterprise Information™ Aviva® for Terminal Servers™ Thin-client Multi-host access for thin-clients solution for multi-host connectivity Corporations are in a constant search to protect their technology investments. Bringing 32-bit applications to older generation desktops, Microsoft® Windows Terminal Server platforms has given traditional PCs a new lease on life. Aviva Solutions’ Aviva for Terminal Servers extends the capabilities of Terminal Server technology by providing PC, Mac and UNIX users with the power and capabilities of full-function, 32-bit SNA emulation, Advantages without compromising on features or performance. Users have, at their own legacy desktops, complete access to all Key Features of the emulation, customization, automation, and programmatic Client Platform Independence – Provides DOS, Windows® 3.11, Windows® 95, Windows® 98, capabilities of a full-function emulator, Windows NT®, Windows® 2000, Mac and UNIX users with the power, speed, and features equal without any loss of functionality. to those of a full-function, 32-bit SNA emulator. State-of-the-art, PC-to-host connectivity is now available to a wide range of Multi-Host Connectivity – Supports all the gateways as well as IP connectivity to IBM hosts operating systems and computers, and standard Telnet connectivity to DEC and UNIX hosts. without large investments in new software and hardware. Aviva HotConnect™ – Unique patent-pending “configure once–detect automatically” technology that provides secure, automatic migration from SNA to TCP/IP networks, Aviva Solutions’ Aviva for Terminal and ensures failsafe connectivity; transparently detects and uses the first available network Servers is a true thin-client solution for connection from a pre-defined list of multiple connection types. -

A Java Implementation of a Portable Desktop Manager Scott .J Griswold University of North Florida

UNF Digital Commons UNF Graduate Theses and Dissertations Student Scholarship 1998 A Java Implementation of a Portable Desktop Manager Scott .J Griswold University of North Florida Suggested Citation Griswold, Scott .,J "A Java Implementation of a Portable Desktop Manager" (1998). UNF Graduate Theses and Dissertations. 95. https://digitalcommons.unf.edu/etd/95 This Master's Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Scholarship at UNF Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in UNF Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of UNF Digital Commons. For more information, please contact Digital Projects. © 1998 All Rights Reserved A JAVA IMPLEMENTATION OF A PORTABLE DESKTOP MANAGER by Scott J. Griswold A thesis submitted to the Department of Computer and Information Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Computer and Information Sciences UNIVERSITY OF NORTH FLORIDA DEPARTMENT OF COMPUTER AND INFORMATION SCIENCES April, 1998 The thesis "A Java Implementation of a Portable Desktop Manager" submitted by Scott J. Griswold in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Computer and Information Sciences has been ee Date APpr Signature Deleted Dr. Ralph Butler Thesis Advisor and Committee Chairperson Signature Deleted Dr. Yap S. Chua Signature Deleted Accepted for the Department of Computer and Information Sciences Signature Deleted i/2-{/1~ Dr. Charles N. Winton Chairperson of the Department Accepted for the College of Computing Sciences and E Signature Deleted Dr. Charles N. Winton Acting Dean of the College Accepted for the University: Signature Deleted Dr. -

Game Streaming Service Onlive Coming to Tablets 8 December 2011, by BARBARA ORTUTAY , AP Technology Writer

Game streaming service OnLive coming to tablets 8 December 2011, By BARBARA ORTUTAY , AP Technology Writer high-definition gaming consoles such as the Xbox 360 and the PlayStation 3. But when they are streamed, the games technically "play" on OnLive's remote servers and are piped onto players' phones, tablets or computers. OnLive users in the U.S. and the U.K. will be able This product image provided by OnLive Inc, shows to use the mobile and tablet service. Games tablets displaying a variety of games using the OnLive available include "L.A. Noire" from Take-Two game controller. OnLive Inc. said Thursday, Dec. 8, Interactive Software Inc. and "Batman: Arkham 2011, that it will now stream console-quality games on City." The games can be played either using the tablets and phones using a mobile application. (AP gadgets' touch screens or via OnLive's game Photo/OnLive Inc.) controller, which looks similar to what's used to play the Xbox or PlayStation. Though OnLive's service has gained traction (AP) -- OnLive, the startup whose technology among gamers, it has yet to reach a mass market streams high-end video games over an Internet audience. connection, is expanding its service to tablets and mobile devices. ©2011 The Associated Press. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, OnLive Inc. said Thursday that it will now stream rewritten or redistributed. console-quality games on tablets and phones using a mobile application. Users could already stream such games using OnLive's "microconsole," a cassette-tape sized gadget attached to their TV sets, or on computers. -

The Videogame Style Guide and Reference Manual

The International Game Journalists Association and Games Press Present THE VIDEOGAME STYLE GUIDE AND REFERENCE MANUAL DAVID THOMAS KYLE ORLAND SCOTT STEINBERG EDITED BY SCOTT JONES AND SHANA HERTZ THE VIDEOGAME STYLE GUIDE AND REFERENCE MANUAL All Rights Reserved © 2007 by Power Play Publishing—ISBN 978-1-4303-1305-2 No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means – graphic, electronic or mechanical – including photocopying, recording, taping or by any information storage retrieval system, without the written permission of the publisher. Disclaimer The authors of this book have made every reasonable effort to ensure the accuracy and completeness of the information contained in the guide. Due to the nature of this work, editorial decisions about proper usage may not reflect specific business or legal uses. Neither the authors nor the publisher shall be liable or responsible to any person or entity with respects to any loss or damages arising from use of this manuscript. FOR WORK-RELATED DISCUSSION, OR TO CONTRIBUTE TO FUTURE STYLE GUIDE UPDATES: WWW.IGJA.ORG TO INSTANTLY REACH 22,000+ GAME JOURNALISTS, OR CUSTOM ONLINE PRESSROOMS: WWW.GAMESPRESS.COM TO ORDER ADDITIONAL COPIES OF THE VIDEOGAME STYLE GUIDE AND REFERENCE MANUAL PLEASE VISIT: WWW.GAMESTYLEGUIDE.COM ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Our thanks go out to the following people, without whom this book would not be possible: Matteo Bittanti, Brian Crecente, Mia Consalvo, John Davison, Libe Goad, Marc Saltzman, and Dean Takahashi for editorial review and input. Dan Hsu for the foreword. James Brightman for his support. Meghan Gallery for the front cover design. -

Mario's Legacy and Sonic's Heritage: Replays and Refunds of Console Gaming History

Mario’s legacy and Sonic’s heritage: Replays and refunds of console gaming history Jaakko Suominen University of Turku / Digital Culture P.O. Box 124 28101 Pori +35823338100 jaakko.suominen at utu.fi ABSTRACT In this paper, I study how three major videogame device manufacturers, Microsoft, Sony and Nintendo use gaming history within their popular console products, Microsoft Xbox 360, Sony PS 3 and Nintendo Wii. These enterprises do not only market new game applications and devices but also recycle classic game themes, game characters as well as classic games themselves. Therefore, these corporations are a part of the phenomenon which can be called retrogaming culture or digital retro economy. The paper introduces the different ways in which the corporations began to use history and how they constructed their digital game market strategies to be compatible with the current retrogaming trend. In addition, the paper introduces a model for different phases of uses of history. The paper is empirically based on literary reviews, recreational computing magazine articles, company websites and other online sources and participatory observation of retrogaming applications and product analyses. Sociological and cultural studies on nostalgia as well as history culture form the theoretical framework of the study. Keywords retrogaming, classic games, history management, uses of history, consoles INTRODUCTION When a game company utilizes its older products to make a new application, when the same company mentions the year it was established in a job advertisement or when it celebrates a game figure’s 20-year anniversary, the company uses history. The use of history can be a discursive act, which underlines continuity and in so doing, for example, the trustworthiness and stability of the firm. -

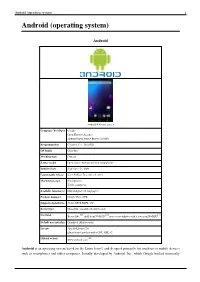

Android (Operating System) 1 Android (Operating System)

Android (operating system) 1 Android (operating system) Android Android 4.4 home screen Company / developer Google Open Handset Alliance Android Open Source Project (AOSP) Programmed in C (core), C++, Java (UI) OS family Unix-like Working state Current Source model Open source with proprietary components Initial release September 23, 2008 Latest stable release 4.4.2 KitKat / December 9, 2013 Marketing target Smartphones Tablet computers Available language(s) Multi-lingual (46 languages) Package manager Google Play, APK Supported platforms 32-bit ARM, MIPS, x86 Kernel type Monolithic (modified Linux kernel) [1] [2] [3] Userland Bionic libc, shell from NetBSD, native core utilities with a few from NetBSD Default user interface Graphical (Multi-touch) License Apache License 2.0 Linux kernel patches under GNU GPL v2 [4] Official website www.android.com Android is an operating system based on the Linux kernel, and designed primarily for touchscreen mobile devices such as smartphones and tablet computers. Initially developed by Android, Inc., which Google backed financially Android (operating system) 2 and later bought in 2005, Android was unveiled in 2007 along with the founding of the Open Handset Alliance: a consortium of hardware, software, and telecommunication companies devoted to advancing open standards for mobile devices. The first publicly available smartphone running Android, the HTC Dream, was released on October 22, 2008. The user interface of Android is based on direct manipulation, using touch inputs that loosely correspond to real-world actions, like swiping, tapping, pinching and reverse pinching to manipulate on-screen objects. Internal hardware such as accelerometers, gyroscopes and proximity sensors are used by some applications to respond to additional user actions, for example adjusting the screen from portrait to landscape depending on how the device is oriented. -

Download Games from Playstation Store to Psp

Download games from playstation store to psp The item will download to your PSP system. Once the content has been copied go to [Games] or [Video]* > [Memory Stick] to install or view your. If the game that you have downloaded (as a purchase or for free) from (PlayStation®Store) is compatible with the PSP™ system, you can copy the game to play it. The native PSN storefront on PSP is closing down, Sony has announced. or download content by accessing the PlayStation Store on their PSPs. PSP titles is quite a draw – especially for fans of classic games and JRPGS. Then go to PSN store on your PSP and check the games that you purchased on SEN (sony entertainment network) in the "downloads list " and. Transferring a PlayStation Store Game to a PSP from a PC. 1. Download and. PSP-How to get free games (demos) at the playstation store - Duration: MrFunny 19, views · 8. Only a short while ago, if you wanted to access the PlayStation Store and all the PSP games and other goodies that it offered for download, you. Why are PSP games on Playstation store, can you buy and download them and play them on your ps3? List of download-only PlayStation 3 games · List of PlayStation 3 disc games released for download List of PlayStation Store TurboGrafx games · List of PlayStation 2 Classics for PlayStation 3 · List of PlayStation 2 games PSP games. PlayStation Store Will Not Be Supported By Media Go From October 24th This will affect those who still use their PSPs to play games and watch videos. -

Moxa Nport Real TTY Driver for Arm-Based Platform Porting Guide

Moxa NPort Real TTY Driver for Arm-based Platform Porting Guide Moxa Technical Support Team [email protected] Contents 1 Introduction ...................................................................................2 2 Porting to the Moxa UC-Series—Arm-based Computer ....................2 2.1 Build binaries on a general Arm platform ...................................................... 2 2.2 Cross-compiler and the Real TTY driver ........................................................ 3 2.3 Moxa cross-compiling interactive script......................................................... 4 2.4 Manually build the Real TTY driver with a cross-compiler ................................ 5 2.5 Deploy cross-compiled binary to target......................................................... 8 3 Porting to Raspberry Pi OS .............................................................9 4 Porting to the Yocto Project on Raspberry Pi ................................ 10 4.1 Prerequisite............................................................................................... 10 4.2 Create a Moxa layer for the Yocto Project..................................................... 11 4.3 Install a Moxa layer into the Yocto Project.................................................... 17 4.4 Deploy the Yocto image in Raspberry Pi ....................................................... 17 4.5 Start the Real TTY driver in Raspberry Pi ..................................................... 18 4.6 Set the default tty mapping to the Real TTY configuration ............................ -

Openbsd Gaming Resource

OPENBSD GAMING RESOURCE A continually updated resource for playing video games on OpenBSD. Mr. Satterly Updated August 7, 2021 P11U17A3B8 III Title: OpenBSD Gaming Resource Author: Mr. Satterly Publisher: Mr. Satterly Date: Updated August 7, 2021 Copyright: Creative Commons Zero 1.0 Universal Email: [email protected] Website: https://MrSatterly.com/ Contents 1 Introduction1 2 Ways to play the games2 2.1 Base system........................ 2 2.2 Ports/Editors........................ 3 2.3 Ports/Emulators...................... 3 Arcade emulation..................... 4 Computer emulation................... 4 Game console emulation................. 4 Operating system emulation .............. 7 2.4 Ports/Games........................ 8 Game engines....................... 8 Interactive fiction..................... 9 2.5 Ports/Math......................... 10 2.6 Ports/Net.......................... 10 2.7 Ports/Shells ........................ 12 2.8 Ports/WWW ........................ 12 3 Notable games 14 3.1 Free games ........................ 14 A-I.............................. 14 J-R.............................. 22 S-Z.............................. 26 3.2 Non-free games...................... 31 4 Getting the games 33 4.1 Games............................ 33 5 Former ways to play games 37 6 What next? 38 Appendices 39 A Clones, models, and variants 39 Index 51 IV 1 Introduction I use this document to help organize my thoughts, files, and links on how to play games on OpenBSD. It helps me to remember what I have gone through while finding new games. The biggest reason to read or at least skim this document is because how can you search for something you do not know exists? I will show you ways to play games, what free and non-free games are available, and give links to help you get started on downloading them. -

Battlefield 3 Psp Iso Download

Battlefield 3 Psp Iso Download Battlefield 3 Psp Iso Download 1 / 2 Download Battlefield 3 PSP (.iso) Gaming Rom Free For Android (Mobiles & Tablets) ... @rawatanuj307 kagak bisa bro di download. 0 replies .... Battlefield 3 is a first-person shooter game which has been released in ISO format full version. Please ignore highly compressed due to the .... Download Battlefield 3 PSP iso game on your Android Phones & Tablets and get Ready to Fight in a Epic Battle.Battlefield 3 is a first-person .... Battlefield 3 Psp Iso Download Game (Ppsspp) DLC Xbox360 Battlefield 3 DLC PACK 4PLAYERs Games Direct. battlefield 3 psp iso download .... Battlefield 3, free and safe download. Battlefield 3 latest version: Awesome next generation first-person shooter.. download game apk, apk downloader, apk games, coc mod, coc mod apk download, download apk gamesbattlefield 3 psp iso game apk, download game apk, .... Teen Patti Gold 2.16 Mod Hack Apk Download - weliketoplaygames. ... gta vice city android apk+obb - weliketoplaygames. ... Silent Hill Shattered Memories PSP iso Android (Eng) Game - weliketoplaygames.. Download Battlefield 3 PSP iso game on your Android Phones & Tablets and get Ready to Fight in a Epic Battle.Battlefield 3 is a first-person ... Those who are loyal fans of the first-person shooter genre will choose Battlefield 3 as one of the super products of this game genre. The game was.. Battlefield 3 (EUR+DLC) PS3 ISO Download for the Sony PlayStation 3/PS3/RPCS3. Game description, information and ISO download page.. Download Battlefield 3 PSP iso game on your Android Phones & Tablets and get Ready to Fight in a Epic Battle.Battlefield 3 is a first-person ... -

Download Linux Ubuntu Psp

Download linux ubuntu psp PPSSPP, a free and open-source Sony PSP emulator, has reached the release a few days ago. Here’s how to install it in Ubuntu , Ubuntu , Ubuntu , and Ubuntu PPSSPP can run your PSP games on your PC in full HD resolution. Ubuntu is a complete desktop Linux operating system, freely available with both community and professional support. This is a PSP Shell made from scratch that. I am trying to do a class project where I install Ubuntu on my PSP. 95 on a PSP (and maybe some of less demanding Linux distributions). I want Linux on PSP with a GUI that can run OpenTTD, go on the Internet and still listen to any update about how to install ubuntu in psp? If you have official Sony firmware on your PSP, it won't be of any use. Here's a screenshot of Ubuntu on my PSP. And its not a genuine ported. Download archive from the official website: QPSPManager is a PSP manager for Linux, Mac OS X and Windows. It has a variety of. First open the terminal the type sudo add-apt- repository ppa:ppsspp/stable click enter then type your password. just ubuntu on a psp slim Install Ubuntu version on your Sony PSP. This is a screenshot of my Sony PSP running firmware GEN 2. I installed Ubuntu v which was admin commands · Installing Ubuntu Linux in Sun VirtualBox. PPSSPP: PSP Emulator For Linux Mint / Ubuntu Installation command to paste in terminal: sudo add-apt. Having problems with PSP? Try this! How To Install PS3 Emulator On Ubutnu , || Install PS3 on.