Fundamentals of Game Design, Adams Adds Much Dr

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Poetics of Reflection in Digital Games

© Copyright 2019 Terrence E. Schenold The Poetics of Reflection in Digital Games Terrence E. Schenold A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Washington 2019 Reading Committee: Brian M. Reed, Chair Leroy F. Searle Phillip S. Thurtle Program Authorized to Offer Degree: English University of Washington Abstract The Poetics of Reflection in Digital Games Terrence E. Schenold Chair of the Supervisory Committee: Brian Reed, Professor English The Poetics of Reflection in Digital Games explores the complex relationship between digital games and the activity of reflection in the context of the contemporary media ecology. The general aim of the project is to create a critical perspective on digital games that recovers aesthetic concerns for game studies, thereby enabling new discussions of their significance as mediations of thought and perception. The arguments advanced about digital games draw on philosophical aesthetics, media theory, and game studies to develop a critical perspective on gameplay as an aesthetic experience, enabling analysis of how particular games strategically educe and organize reflective modes of thought and perception by design, and do so for the purposes of generating meaning and supporting expressive or artistic goals beyond amusement. The project also provides critical discussion of two important contexts relevant to understanding the significance of this poetic strategy in the field of digital games: the dynamics of the contemporary media ecology, and the technological and cultural forces informing game design thinking in the ludic century. The project begins with a critique of limiting conceptions of gameplay in game studies grounded in a close reading of Bethesda's Morrowind, arguing for a new a "phaneroscopical perspective" that accounts for the significance of a "noematic" layer in the gameplay experience that accounts for dynamics of player reflection on diegetic information and its integral relation to ergodic activity. -

Macroeconomic Theory and Policy Lecture 2: National Income Accounting

ECO 209Y Macroeconomic Theory and Policy Lecture 2: National Income Accounting © Gustavo Indart Slide1 Gross Domestic Product Gross Domestic Product (GDP) is the value of all final goods and services produced in Canada during a given period of time That is, GDP is a flow of new products during a period of time, usually one year We can use three different approaches to measure GDP: Production approach Expenditure approach Income approach © Gustavo Indart Slide 2 Measuring GDP Production Approach –We can measure GDP by measuring the value added in the production of goods and services in the different industries (e.g., agriculture, mining, manufacturing, commerce, etc.) Expenditure Approach –We can measure GDP by measuring the total expenditure on final goods and services by different groups (households, businesses, government, and foreigners) Income Approach –We can measure GDP by measuring the total income earned by those producing goods and services (wages, rents, profits, etc.) © Gustavo Indart Slide 3 Flow of Expenditure and Income Labour, land FACTORS Labour, land & capital MARKETS & capital Wages, rent & interest HOUSEHOLDS FIRMS Expenditures on goods & services Goods & services GOODS Goods & MARKETS services © Gustavo Indart Slide 4 Measuring GDP Current Output –GDP includes only the value of output currently produced. For instance, GDP includes the value of currently produced cars and houses but not the sales of used cars and old houses Market Prices –GDP values goods at market prices, and the market price of a good includes -

Learning Board Game Rules from an Instruction Manual Chad Mills A

Learning Board Game Rules from an Instruction Manual Chad Mills A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science University of Washington 2013 Committee: Gina-Anne Levow Fei Xia Program Authorized to Offer Degree: Linguistics – Computational Linguistics ©Copyright 2013 Chad Mills University of Washington Abstract Learning Board Game Rules from an Instruction Manual Chad Mills Chair of the Supervisory Committee: Professor Gina-Anne Levow Department of Linguistics Board game rulebooks offer a convenient scenario for extracting a systematic logical structure from a passage of text since the mechanisms by which board game pieces interact must be fully specified in the rulebook and outside world knowledge is irrelevant to gameplay. A representation was proposed for representing a game’s rules with a tree structure of logically-connected rules, and this problem was shown to be one of a generalized class of problems in mapping text to a hierarchical, logical structure. Then a keyword-based entity- and relation-extraction system was proposed for mapping rulebook text into the corresponding logical representation, which achieved an f-measure of 11% with a high recall but very low precision, due in part to many statements in the rulebook offering strategic advice or elaboration and causing spurious rules to be proposed based on keyword matches. The keyword-based approach was compared to a machine learning approach, and the former dominated with nearly twenty times better precision at the same level of recall. This was due to the large number of rule classes to extract and the relatively small data set given this is a new problem area and all data had to be manually annotated. -

Game Streaming Service Onlive Coming to Tablets 8 December 2011, by BARBARA ORTUTAY , AP Technology Writer

Game streaming service OnLive coming to tablets 8 December 2011, By BARBARA ORTUTAY , AP Technology Writer high-definition gaming consoles such as the Xbox 360 and the PlayStation 3. But when they are streamed, the games technically "play" on OnLive's remote servers and are piped onto players' phones, tablets or computers. OnLive users in the U.S. and the U.K. will be able This product image provided by OnLive Inc, shows to use the mobile and tablet service. Games tablets displaying a variety of games using the OnLive available include "L.A. Noire" from Take-Two game controller. OnLive Inc. said Thursday, Dec. 8, Interactive Software Inc. and "Batman: Arkham 2011, that it will now stream console-quality games on City." The games can be played either using the tablets and phones using a mobile application. (AP gadgets' touch screens or via OnLive's game Photo/OnLive Inc.) controller, which looks similar to what's used to play the Xbox or PlayStation. Though OnLive's service has gained traction (AP) -- OnLive, the startup whose technology among gamers, it has yet to reach a mass market streams high-end video games over an Internet audience. connection, is expanding its service to tablets and mobile devices. ©2011 The Associated Press. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, OnLive Inc. said Thursday that it will now stream rewritten or redistributed. console-quality games on tablets and phones using a mobile application. Users could already stream such games using OnLive's "microconsole," a cassette-tape sized gadget attached to their TV sets, or on computers. -

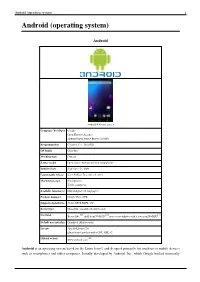

Android (Operating System) 1 Android (Operating System)

Android (operating system) 1 Android (operating system) Android Android 4.4 home screen Company / developer Google Open Handset Alliance Android Open Source Project (AOSP) Programmed in C (core), C++, Java (UI) OS family Unix-like Working state Current Source model Open source with proprietary components Initial release September 23, 2008 Latest stable release 4.4.2 KitKat / December 9, 2013 Marketing target Smartphones Tablet computers Available language(s) Multi-lingual (46 languages) Package manager Google Play, APK Supported platforms 32-bit ARM, MIPS, x86 Kernel type Monolithic (modified Linux kernel) [1] [2] [3] Userland Bionic libc, shell from NetBSD, native core utilities with a few from NetBSD Default user interface Graphical (Multi-touch) License Apache License 2.0 Linux kernel patches under GNU GPL v2 [4] Official website www.android.com Android is an operating system based on the Linux kernel, and designed primarily for touchscreen mobile devices such as smartphones and tablet computers. Initially developed by Android, Inc., which Google backed financially Android (operating system) 2 and later bought in 2005, Android was unveiled in 2007 along with the founding of the Open Handset Alliance: a consortium of hardware, software, and telecommunication companies devoted to advancing open standards for mobile devices. The first publicly available smartphone running Android, the HTC Dream, was released on October 22, 2008. The user interface of Android is based on direct manipulation, using touch inputs that loosely correspond to real-world actions, like swiping, tapping, pinching and reverse pinching to manipulate on-screen objects. Internal hardware such as accelerometers, gyroscopes and proximity sensors are used by some applications to respond to additional user actions, for example adjusting the screen from portrait to landscape depending on how the device is oriented. -

Games and Rules

Requirements for a General Game Mechanics Framework Imre Hofmann In this article I will apply a meta-theoretical approach to the question of how a game mechanics framework has to be designed in order to fulfil its task of ade- quately depicting or modeling the reality of game mechanics. I had two aims in mind when starting my research. I studied existing game theories and three game mechanics theories in particular in order to evaluate the state of the art of game mechanics theory. (Descriptive aim) The second aim followed on from these studies. With the results of my research I wanted to define the attributes a com- prehensive and general game mechanics theory might or – rather – needed to have. What are the general properties that such a theory should display? (Norma- tive aim) In my opinion the underlying mechanics of a game may be regarded in some way as its centerpiece. The reasons for this shall become clear over the course of this article. To begin with, I would like to make two terminological clarifications. First, I am not going to examine different game mechanics and typologies or categories of game mechanics. Instead, I will take a theoretical step backwards, so to speak, on the meta-level by analyzing and comparing different theories of game me- chanics (which themselves suggest categories and typologies). Secondly, I will use the expressions “game mechanics theory” “(game mechanics) framework” and “(game mechanics) model” synonymously. In my research I focused mainly on the following three key theories of game mechanics: 1. Carlo Fabricatore’s Gameplay and Game Mechanics Design (2007) 2. -

Week 3 Day 1: Designing Games with Conditionals

INTRODUCTION | CYBER ARCADE: PROGRAMMING AND MAKING WITH MICRO:BIT 3-1 | ELEMENTARY WEEK 3 DAY 1: DESIGNING GAMES WITH CONDITIONALS INTRODUCTION This week makers continue to use the Micro:bit microcontroller and begin coding and designing interactive games and art. ESSENTIAL QUESTIONS • How can we use code and math to create a fun game? • What is a conditional statement? • How do artists, engineers, and makers solve problems when they’re working? LEARNING OUTCOMES 1. Learn how to use code and conditionals to create a game. 2. Engage in project-based learning through problem-solving and troubleshooting by creating a game using a Micro:bit microcontroller and code. TEACHERLESSON | RESOURCE CYBER ARCADE: | CYBER PROGRAMMING ARCADE: PROGRAMMING AND MAKING AND WITH MAKING MICRO:BIT WITH MICRO:BIT 3-23-2 | | ELEMENTARY ELEMENTARY VOCABULARY Conditional: Set of rules performed if a certain condition is met Game mechanics: Basic actions, processes, visuals, and control mechanisms that are used to make a game Game designer: Person responsible for designing game storylines, plots, objectives, scenarios, the degree of difficulty, and character development Game engineer: Specialized software engineers who design and program video games Troubleshooting: Using resources to solve issues as they arise TEACHERLESSON | RESOURCE CYBER ARCADE: | CYBER PROGRAMMING ARCADE: PROGRAMMING AND MAKING AND WITH MAKING MICRO:BIT WITH MICRO:BIT 3-33-3 | | ELEMENTARY ELEMENTARY MATERIALS LIST EACH PAIR OF MAKERS NEEDS: • Micro:bit microcontroller • Laptop with internet connection • USB to micro-USB cord • USB flash drive • External battery pack • AAA batteries (2) • Notebook TEACHER RESOURCE | CYBER ARCADE: PROGRAMMING AND MAKING WITH MICRO:BIT 3-4 | ELEMENTARY They can also use the Troubleshooting Tips, search the internet for help, TEACHER PREP WORK or use the tutorial page on the MakeCode website. -

Computer Game Flow Design, ACM Computers in Entertainment, 4, 1

LJMU Research Online Taylor, MJ, Baskett, M, Reilly, D and Ravindran, S Game theory for computer games design http://researchonline.ljmu.ac.uk/id/eprint/7332/ Article Citation (please note it is advisable to refer to the publisher’s version if you intend to cite from this work) Taylor, MJ, Baskett, M, Reilly, D and Ravindran, S (2017) Game theory for computer games design. Games and Culture, 14 (7-8). pp. 843-855. ISSN 1555-4139 LJMU has developed LJMU Research Online for users to access the research output of the University more effectively. Copyright © and Moral Rights for the papers on this site are retained by the individual authors and/or other copyright owners. Users may download and/or print one copy of any article(s) in LJMU Research Online to facilitate their private study or for non-commercial research. You may not engage in further distribution of the material or use it for any profit-making activities or any commercial gain. The version presented here may differ from the published version or from the version of the record. Please see the repository URL above for details on accessing the published version and note that access may require a subscription. For more information please contact [email protected] http://researchonline.ljmu.ac.uk/ Game theory for computer games design Abstract Designing and developing computer games can be a complex activity that may involve professionals from a variety of disciplines. In this article, we examine the use of game theory for supporting the design of game play within the different sections of a computer game, and demonstrate its application in practice via adapted high-level decision trees for modelling the flow in game play and payoff matrices for modelling skill or challenge levels. -

Demand Composition and the Strength of Recoveries†

Demand Composition and the Strength of Recoveriesy Martin Beraja Christian K. Wolf MIT & NBER MIT & NBER September 17, 2021 Abstract: We argue that recoveries from demand-driven recessions with ex- penditure cuts concentrated in services or non-durables will tend to be weaker than recoveries from recessions more biased towards durables. Intuitively, the smaller the bias towards more durable goods, the less the recovery is buffeted by pent-up demand. We show that, in a standard multi-sector business-cycle model, this prediction holds if and only if, following an aggregate demand shock to all categories of spending (e.g., a monetary shock), expenditure on more durable goods reverts back faster. This testable condition receives ample support in U.S. data. We then use (i) a semi-structural shift-share and (ii) a structural model to quantify this effect of varying demand composition on recovery dynamics, and find it to be large. We also discuss implications for optimal stabilization policy. Keywords: durables, services, demand recessions, pent-up demand, shift-share design, recov- ery dynamics, COVID-19. JEL codes: E32, E52 yEmail: [email protected] and [email protected]. We received helpful comments from George-Marios Angeletos, Gadi Barlevy, Florin Bilbiie, Ricardo Caballero, Lawrence Christiano, Martin Eichenbaum, Fran¸coisGourio, Basile Grassi, Erik Hurst, Greg Kaplan, Andrea Lanteri, Jennifer La'O, Alisdair McKay, Simon Mongey, Ernesto Pasten, Matt Rognlie, Alp Simsek, Ludwig Straub, Silvana Tenreyro, Nicholas Tra- chter, Gianluca Violante, Iv´anWerning, Johannes Wieland (our discussant), Tom Winberry, Nathan Zorzi and seminar participants at various venues, and we thank Isabel Di Tella for outstanding research assistance. -

Listing Statement Cse Form 2A Nextech Ar Solutions Corp

LISTING STATEMENT CSE FORM 2A NEXTECH AR SOLUTIONS CORP. October 24, 2018 TABLE OF CONTENTS GLOSSARY 1 CORPORATE STRUCTURE 3 GENERAL DEVELOPMENT OF THE BUSINESS 4 USE OF AVAILABLE FUNDS 18 SELECTED CONSOLIDATED FINANCIAL INFORMATION 19 DIVIDENDS 20 MANAGEMENT’S DISCUSSION AND ANALYSIS 20 MARKET FOR SECURITIES 20 CONSOLIDATED CAPITALIZATION 21 OPTIONS TO PURCHASE SECURITIES 21 DESCRIPTION OF SECURITIES 22 ESCROWED SECURITIES 23 PRINCIPAL SHAREHOLDERS 24 DIRECTORS AND OFFICERS 24 CAPITALIZATION 28 EXECUTIVE COMPENSATION 32 INDEBTEDNESS OF DIRECTORS AND EXECUTIVE OFFICERS 34 RISK FACTORS 34 PROMOTERS 38 LEGAL PROCEEDINGS 38 INTEREST OF MANAGEMENT AND OTHERS IN MATERIAL TRANSACTIONS 39 AUDITORS, TRANSFER AGENT AND REGISTRAR 39 MATERIAL CONTRACTS 39 INTERESTS OF EXPERTS 39 OTHER MATERIAL FACTS 40 FINANCIAL STATEMENTS 40 SCHEDULE “A-1” – FINANCIAL STATEMENTS SCHEDULE “A-2” – CARVE OUT FINANCIAL STATEMENTS SCHEDULE “B” – MANAGEMENT DISCUSSION AND ANALYSIS GLOSSARY In this Listing Statement, unless otherwise defined herein or unless there is something in the subject matter inconsistent therewith, the following terms have the respective meanings set out below, words importing the singular number include the plural and vice versa and words importing any gender include all genders. “2D” means two dimensional. “3D” means three dimensional. “adMob” is Google’s advertising platform for promoting and monetizing mobile apps. adMob allows app developers to promote their apps through in-app ads, monetize their apps by enabling in-app advertising, and provide intelligent insights through Google Analytics. “Android” means an open-source operating system used for smartphones and tablet computers. “app” means an application, especially as downloaded by a user to a mobile device. -

3. the Distortion in Consumer Goods This Section Calculates the Welfare Cost of Distortions in the Allocation of Consumer Goods

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Bjertnæs, Geir H. Working Paper The Welfare Cost of Market Power. Accounting for Intermediate Good Firms Discussion Papers, No. 502 Provided in Cooperation with: Research Department, Statistics Norway, Oslo Suggested Citation: Bjertnæs, Geir H. (2007) : The Welfare Cost of Market Power. Accounting for Intermediate Good Firms, Discussion Papers, No. 502, Statistics Norway, Research Department, Oslo This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/192484 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die in der dort Content Licence (especially Creative Commons Licences), you genannten Lizenz gewährten Nutzungsrechte. may exercise further usage rights as specified in the indicated licence. www.econstor.eu Discussion Papers No. 502, April 2007 Statistics Norway, Research Department Geir H. Bjertnæs The Welfare Cost of Market Power Accounting for Intermediate Good Firms Abstract: The market power of firms in intermediate good markets is found to generate a substantial welfare cost. -

1 Non-Rival Productive Inputs

1 Non-rival productive inputs. Consider a general production technology: Y = Y (A ; K ; L ) t t t t (1) K L A We conventionally label t as “capital”, t as labor and t as an index of technical knowledge. I will now try to be more fundamental, and single out a classi…cation of the productive inputs which is not based on some statistical aggregate, but, rather, on some economic properties which are relevant for the problems which we study in the theory of growth. Let us recall some basic notions of public economics. Private good RIVAL + EXCLUDABLE ² ´ Public (collective) good NON-RIVAL + NON-EXCLUDABLE ² ´ EXCLUDABILITY - problem of property rights. A good is perfectly ² excludable when the holder can withhold the bene…ts associated with the commodity from others without incurring signi…cant costs (an ex- ample of non excludable good is …sh in a certain segment of the ocean). RIVALROUSNESS - A good is rival in nature when the use of that ² good by one agent preclude the simultaneous use of the same good by other agents. An example of non-rival good is radio broadcast. Let me add a notion which is relevant in growth theory. REPRODUCIBILITY - An input is reproducible in nature if it can ² be accumulated in time by (directly or indirectly) foregoing present consumption. The stock of land is the most obvious example of non- reproducible factor. However, also goods which are accumulated ac- cording to some exogenous (e.g. demographic) dynamics enter this group. 1 K L In general, t is a reproducible, private input, while t is a non-reproducible private input.